Want to reduce child neglect? Put more money in the pockets of poor families

Are we looking in the wrong places to combat child neglect? That’s what a new paper from researchers suggests.

Is our country looking in the wrong places in our efforts to prevent child neglect? By focusing on individual families accused of maltreatment, are we letting society off the hook?

That is the contention of a new paper by researchers at the University of Connecticut, University of Illinois and Georgia Tech, who say we can reduce child neglect by putting more money in the pockets of poor families.

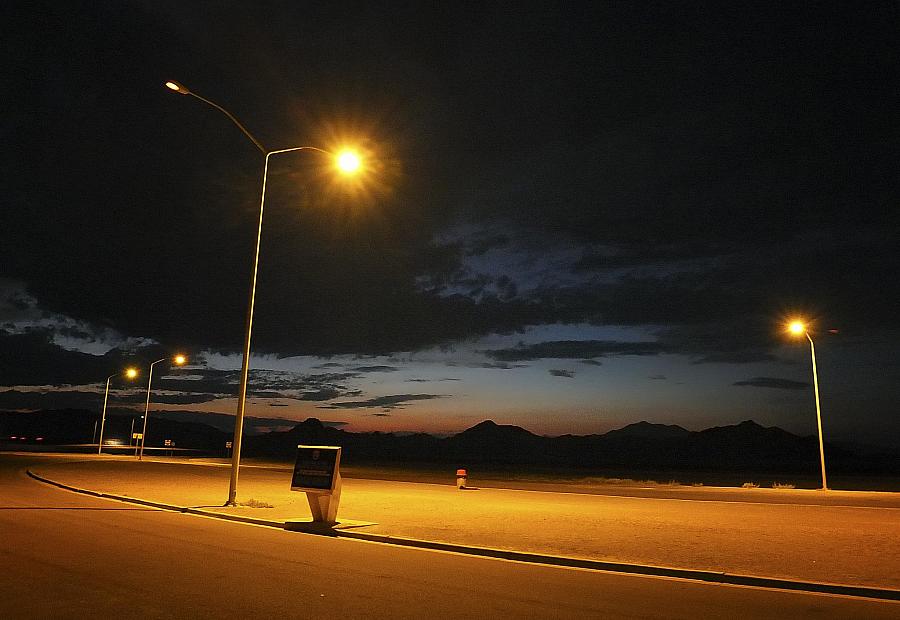

The authors say our current approach is a version of the "streetlight effect."

"A guy is looking for his keys and looking under the streetlamp and someone says, Why are you looking for your keys under the streetlamp?’ He says, 'Well, that's where the light is,'" said one of the paper's authors, Kerri Raissian, an assistant professor of public policy at the University of Connecticut.

"I think that's what we do a lot with child maltreatment prevention,” she said. “We look where the light is."

In Raissian’s metaphor, the guy looking for his keys is child protective services, stuck narrowly looking only at the families under investigation for maltreatment — usually for neglect.

Nationally, child protective service agencies get about 4.1 million referrals a year, involving 7.3 million children, the researchers noted. Nearly three-fourths were related to neglect. Likewise, of the 1,670 American child fatalities in 2015, 73 percent involved neglect.

While the rate of child sexual abuse dropped 64 percent and physical abuse fell by 53 percent between 1992 and 2017, neglect declined by just 12 percent, according to the Crimes Against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire.

"Neglect ... is seemingly intractable," Raissian said. (She presented her findings at inaugural conference of the National Foundation to End Child Abuse and Neglect, or EndCAN, last month in Denver.)

That's because, the researchers contend, neglect is tied mostly to poverty. But public policies to improve families’ economic security have been found to cut down their chances of mistreating their kids.

For every $1 increase in the minimum wage, neglect reports decline by 9.6%, according to a 2017 study by Raissian and Lindsey Bullinger of the Georgia Institute of Technology. The decrease was concentrated among children 12 and younger.

Meanwhile, upping the earned income tax credit reduces child neglect and the chances a family becomes involved with child protective services, particularly among low-income single mothers, according to a 2017 study by researchers at the University of Wisconsin, University of Texas and Columbia University.

And increasing child support payments also lowers the risk of child maltreatment, according to research at the University of Wisconsin and Louisiana State University in 2013. This can be done by allowing parents who receive cash help — known as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families — to get all of their child support rather than letting states keep some of it to reimburse itself for that aid.

“If you really take a hard look at most forms of neglect, you move upstream and it’s … economics, it’s housing, it’s health care stresses,” Peter Pecora, managing director of research services for Casey Family Programs and a professor of social work for the University of Washington, said at the recent EndCAN conference. Parents dealing with those chronic stressors have less resources and mental energy to devote to raising their children.

States such as California, Colorado, Minnesota and Wisconsin are even starting to experiment with giving families financial counseling and short-term grants as a way to prevent abuse and neglect.

The paper’s authors say the nation should treat child maltreatment like it did automobile safety.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers the drop in motor vehicle deaths one of the top 10 public health achievements of the 20th century. That decline happened by requiring seat belt use, placing kids in special car seats, and cracking down on drunken driving and speeding.

"Imagine a world where neglect prevention mirrors our approach to car safety," Raissian said, "where interventions are applied to all cars and all drivers, not just those who are statistically likely to be in an accident or who have already been in one.”