WaPo’s William Wan wants his stories to make people care about our overlooked mental health crisis

During the height of the pandemic, Washington Post enterprise reporter Willian Wan covered whatever his editors requested during his regular workday, from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

But from 5 a.m. to 10 a.m. was his time, which he spent reporting a series on the shadow pandemic of mental health crises: loneliness, drug overdose and suicides.

“I’ve always felt that mental health has never been important to newspapers, to society,” Wan told 2023 Center for Health Journalism California Health Equity Fellowship participants this week.

Wan said he felt a strong personal desire to report on these important yet often overlooked aspects of health – even if he had to do the reporting on his own time. Earlier this week, he shared with fellows the stories behind some of his most compelling recent pieces and offered strategies for approaching reporting with both sensitivity and confidence in one’s mission as a journalist.

Powerful narratives, investigative rigor

Over decades of reporting, Wan has covered everything from religion to China to mass shootings. He ultimately was able to write his job description: writing about people suffering on the margins of society, often with mental health challenges. In his stories, he combines powerful narrative storytelling with investigative facts and figures.

For example, Wan received a tip from a Yale University student who said students were hiding their suicidal thoughts in fear of being forced to leave the school and later reapply. Wan spent months following one student’s journey through leaving and the reapplication process, which resulted in the 2022 story “What if Yale finds out?” Earlier this year, Yale announced changes to its mental health policies.

He also explored what happened to teenagers forced to spend weeks waiting in the emergency department waiting for a psychiatric bed to open, a project he pursued through as a Center for Health Journalism Data Fellow. For that story, he requested a data for emergency room patients in Maryland hospitals. He sifted through the numbers to find psychiatric patients and children, combining data on wait times with a human narrative.

Another story on suicides at Maryland’s iconic Chesapeake Bay Bridge proved tremendously challenging, since the agencies involved did not want to talk. Some feared discussing the problem would leave to “contagion,” or more people jumping. Wan wanted to counter the apathy that became apparent during one man’s attempted suicide on the bridge. Travelers eager to get to the beach complained about the traffic jam on social media and mocked the individual.

William Wan talks to fellows at the 2023 California Health Equity Fellowship.

(Photo by Cassandra Garibay/CHJ)

Over time, Wan connected with the mom whose son had tried to jump off the bridge, a story he combined with a broader look at the number of attempts, deaths, and efforts to prevent suicide attempts there.

“My goal last year was to do the narrative stuff that moves people, but have hard actual investigative things to try to push it forward,” he said.

Readying yourself for the work

When Wan prepares to interview a key source in a difficult story, he’ll often sit in the car beforehand, reminding himself why he’s doing this interview. He tries to stay mindful of his reaction to traumatic events during the conversation.

“It’s a mistake to focus on yourself and how bad you’ll feel,” he said. “It’s not about you.”

At the same time, self-care is important especially when covering such weighty topics. Wan, a husband and father of two, said he struggles with working too much. He agonizes over the writing, and worries about the well-being of the people entrusting their story to him.

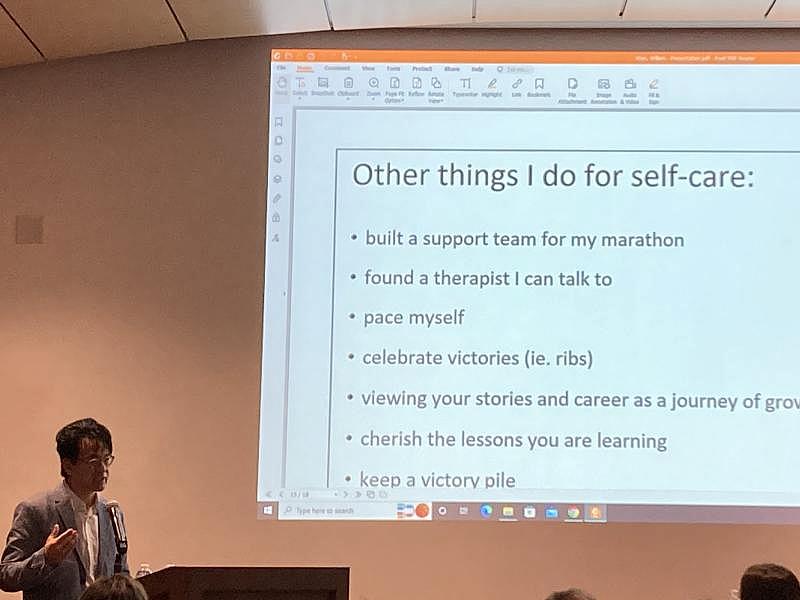

Wan puts quotes and insights on a wall behind his desk to remember to focus on compassion for himself as well. He paces himself, celebrates successes, and keeps a victory pile of stories that show the strength and impact of his work to buoy himself when struggling with a story. He tries to conjure a growth mindset, focusing less on the success of any given story than on his own learning journey as a reporter.

In recent years, that has led him to a grudging acceptance that self-promotion isn’t always a bad thing. Seeking promotions and awards helps create that broader recognition that stories of marginalized people matter. They help him make the case to editors that reporting time and resources should be devoted to them.

“That’s the only way I get to do these stories,” he said.

Reporting on trauma

Through his trauma and mental health coverage, Wan has learned a few tips and strategies:

- Be human first: Explain to sources why you want to cover the story. Consider talking off the record first so they can share their concerns openly.

- Give sources some control: Often, mental health crises involve a loss of control. Wan tries to put the ball in the source’s court by asking what information they want to share with the world.

- Understand your motives and believe in yourself: The more nervous you are, the more those nervous your sources will likely be. Wan tries to clarify his broader motivations for writing the story in advance. This way, he doesn’t feel “like a parasite” seeking out people in pain.

- Put in time, effort with sources: Wan often eases his way toward the more difficult questions. Sometimes, he’ll spend two or three days with a source before bringing up the painful events. At the end of the interview, he tries to bring the conversation back to “a safe place” by asking them about something positive in their lives — even if it’s just sitting on the porch and chatting about someone’s dog. He’ll follow up in-person interviews with a text to check in.

- Review the information: Before publication, Wan goes through the material he plans to use and address any source concerns or questions. During the story on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, for example, the mother requested her son’s name not be used. They had a conversation and agreed to only use her name. He also calls sources the day the story runs to check in, a practice that he says helps hold himself accountable.

- Standing out: When covering a story with widespread media attention, Wan considers what might be different or unique about his approach, or he’ll approach the person at a different time. Sometimes, he’ll write a source a short letter seeking an interview, which helps distinguish his approach from other reporters seeking a quick sound bite.