When it comes to healthy living, docs don't practice what they preach

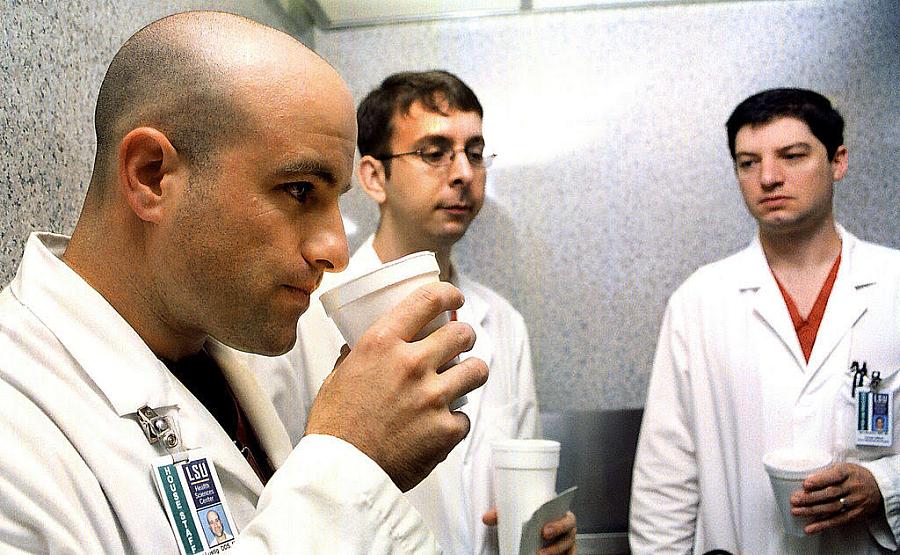

Photo: Mario Villafuerte /Getty Images

The American College of Physicians national meeting was in full swing. Every year, internal medicine physicians gather to hear the latest medical information and find out how they should update the ways in which they practice. In a Washington, D.C., convention center, doctors practiced starting neck IVs and listening to heart sounds while learning that cholesterol panels don’t always require patients to fast first.

Perusing the snack table during a break, I found an array of sweets. The options consisted of bagels, sweetened yogurt, and muffins. There was even candy. More candy was on offer at many of the exhibition booths run by drug companies and medical device companies. Thirsty? Full-sugar soda was readily available.

Doctors often operate their own bodies differently than what they prescribe. Family doctors, cardiologists, and internists say things like, “Eat a low-carb diet, eat more vegetables, stop smoking” — up to 20 times per day, yet their actions suggest an attitude somewhere in between “I’m invincible” and “I’m too busy to be healthy.” In the hospital, you hear many health professionals clucking about their obese patients who needed heart stents. Meanwhile, they chow down on cheesesteaks in the hospital cafeteria, their rotund bellies requiring extra-large white coats.

Why do they do this? A culture of speed — one is doing something wrong if one is not working and generating money — has contributed to doctors’ hypocritical behavior. It starts in medical school and residency: one can never spend too much time in the anatomy lab, and one can always create more detailed flashcards for the medical licensing examination. Working 30-hour shifts, followed by a commute and frantically trying to attend to chores, is a sure way to override thoughts of preparing healthy meals or going for a quick run. Compared to the grind of hospital shifts or studying, these activities seem like time-wasters when takeout is so quick and there are charts to be dictated. In employed positions, management pressures doctors to pack their schedules with so many patients that charting work spills into the precious after-work hours that might otherwise be used for cooking or exercising. Private practice doctors, seeking to match salaries from the heyday of insurance company payments, push themselves just as hard.

Doctors self-destruct with substances as well. Among a trio of lung specialists I once knew, only one was not a chain smoker himself. They would literally pronounce a patient dead of lung complications related to smoking, walk outside, and smoke off the stress. While several studies suggest that the rate of alcoholism among doctors isn’t more than that of non-doctors, others think that this is a gross undercount. Doctors who drink alcohol in an unhealthy way are also more likely to suffer burnout and disconnection from patients. I would wager that poor diet, lack of exercise, and long hours are just as bad for creating burnout, which is on the verge of being declared a public health emergency.

Medical professionals of all types need to reclaim their rights to great health, even if it means sacrificing some income to get more sleep, prepare a salad, or cycle to work. Patients need to see that we consider good health to be worth pursuing in order to be inspired to take such steps themselves.

**