Why isn’t the nation’s maternal mortality problem generating more headlines?

If anyone should know about a new Tennessee law that will help reduce preventable pregnancy-related deaths in her state, it’s Beth Lee Frazer.

In 2008, after nearly dying from HELLP syndrome (a severe form of preeclampsia) and losing her 20-week twins, the Tennessee resident and three-time mom became an outspoken advocate and fundraiser for preeclampsia research and improved pregnancy care.

Yet even though she knew there was pending legislation, Frazer still had no idea that on May 2, Tennessee passed the Maternal Mortality Review and Prevention Act of 2016. This law allows for the creation of an expert panel that will investigate how and why women are dying from pregnancy-related causes and complications in the state, and compile related data.

She found out about the vote through me, after I contacted her to ask if she had read any news about it.

“It’s hard to explain to someone who hasn’t faced a life-threatening pregnancy complication why this is so, so important,” she told me. “This makes me hugely proud of my state. Tennessee is standing up for the health of our mothers.”

Almost no news coverage of four new state laws addressing problem

Tennessee was one of four states that passed maternal mortality review board laws in the most recent round of legislative sessions, along with Washington, North Carolina and South Carolina.

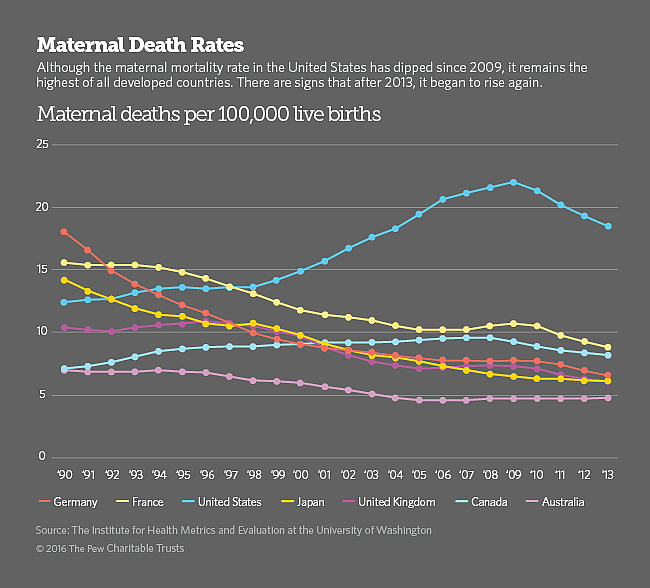

This is an important trend — both on the state level and nationally — as it’s aimed straight at a vexing problem: The United States now has the highest maternal death rate among developed nations.

State-level maternal mortality review boards have been repeatedly pinpointed by the CDC and the Association of Maternal & Child Health Programs as a crucial way to get that statistic down, as explained in this Pew Stateline look at the issue.

Yet, this would be hard to know about from just reading the news. Based on a news search I conducted in those states in early May, I found meager coverage of the issue — both while it was a pending bill and after it passed and became law. For example:

-

In February, The Tennessean wrote a five-paragraph story about the pending bill. I could find no other examples of coverage from any Tennessee news outlet.

-

Last year, South Carolina’s The Post and Courier wrote a well-reported, thorough piece about the alarming maternal death rates in the state, but hasn’t appeared to follow up on the news of the state law. No other outlets in South Carolina appear to have written about the bill or law either.

-

I could find no news about the bill or the law in North Carolina, except for a tiny mention in a state health care policy news site. (The majority of the article was devoted to the portion of the bill establishing a 72-hour waiting period for abortions, a policy topic that did make state and national news.)

-

In Washington, the new law got one brief mention in a larger statehouse round up of women’s health issues by a nonprofit news service, and the bill did garner a small segment on local public radio.

This is a patient safety issue for women and babies

In 2010, the Joint Commission — the nation’s top health care accrediting organization — issued a “sentinel event alert” about the increasing rate of U.S. women dying from pregnancy-related causes. “For every woman who dies, there are 50 who are very ill, suffering significant complications of pregnancy, labor and delivery,” Dr. William Callaghan, a senior CDC scientist, said in the alert.

Many of the commission’s sentinel events are considered failures in patient safety: rape in a hospital setting, surgery on the wrong limb, an abduction of a newborn. By adding maternal mortality to that list, the commission signaled it was time for the U.S. health care system as a whole to get serious about this problem. As the National Partnership for Maternal Safety notes, "a significant proportion of morbidity and mortality in these conditions has been found to be due to missed opportunities to improve outcomes."

With such a stern warning, one would expect that by now curious reporters would have extensively dug into the problem — and explored possible solutions, too, like these laws.

However, several journalists and public health experts I spoke to said this just hasn’t happened to any notable degree — and this is exemplified by the recent gap in coverage on the new state laws.

The reasons I heard ranged from straightforward, such as fewer statehouse reporters and journalists in general, to hard-to-prove, like the persistent myth that U.S. women no longer die in childbirth. Political controversy in other areas of women's health was often cited, too.

“Because of the political battles around access to abortion and contraception, it seems like maternal health (which people can generally agree on) gets pushed to the backburner,” said Elizabeth Dawes Gay, a writer and reproductive health advocate based in Washington, D.C., via email. “There are 'newsier' things happening and media may feel like they have to prioritize other important reproductive health and gender topics.”

'I didn’t realize we were last — absolute last — among Western countries'

(Click to enlarge) A number of causes have been identified by the National Partnership for Maternal Safety, including both healthcare quality and safety problems, and more complicated patient demographics, such as older, heavier women having babies. Graphic courtesy Pew Charitable Trust

It’s not just state news that gets overlooked. I found Dawes Gay because she appears to be the only journalist who wrote about an April congressional briefing about this problem.

Trudy Lieberman, a 40-year veteran health care journalist and contributing editor to this site, also pointed out the lack of interest hospitals and doctors have in promoting awareness about this problem — especially given that the headlines can be far from complimentary.

“They’re interested in pushing the stuff they want you to write about,” she said. “If hospitals aren’t pushing it, is the local press going to write about it? They’re telling writers about a new cancer wing or kidney machine.”

One example: Although an entire day was devoted to the topic of maternal mortality during the just-held 2016 meeting of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, this wasn't touted in their press materials.

Lack of PR for the problem means that many journalists simply have no idea there’s even a problem to report on. Michael Ollove, a Pew Stateline writer who was one of the few journalists to write about the recent CDC push for state-level maternal mortality review boards, says he stumbled upon the story idea while watching a presentation at a health journalism conference. He was stunned by what he saw.

“I didn’t realize we were last — absolute last — among Western countries,” he said.

'There is a great story out there waiting to be written about'

At least some of the silence might also be because it’s an issue that disproportionately affects the most disenfranchised women, Dawes Gay said.

While state maternal mortality review boards are only one part of the solution — as Gay points out, they aren’t likely to solve the social, economics and racial issues at play — experts say they can play a vitally important role in swinging the grim numbers back to something the U.S. can once again be proud of.

“There is a great story out there waiting to be written about strategies to accomplish that goal,” says Sharon Dunwoody, a science communication expert and professor emeritus in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “A reporter could spend some time in the historical weeds, offer comparative statistics that puts the U.S. to shame, reflect on the politics of focusing on women’s health issues, and look for evidence that these maternal mortality review boards actually do reduce death of women for pregnancy-related causes," Dunwoody said.

HELLP survivor Beth Lee Frazer couldn’t agree more.

“Women die, every day, bringing life into this world," she said. "But it has never been given the attention it deserves."

Joy Victory is the deputy managing editor of HealthNewsReview.org and tweets as @thejoyvictory. She also serves as a patient adviser to the Preeclampsia Foundation.

[Photo by Tatiana Vdb via Flickr.]