With 13,000 gang members in Orange County, the push is on to curb crime and recruitment

Denisse Salazar wrote this story, part of a series, while participating in the USC Center for Health Journalism’s California Fellowship.

Other stories in the series include:

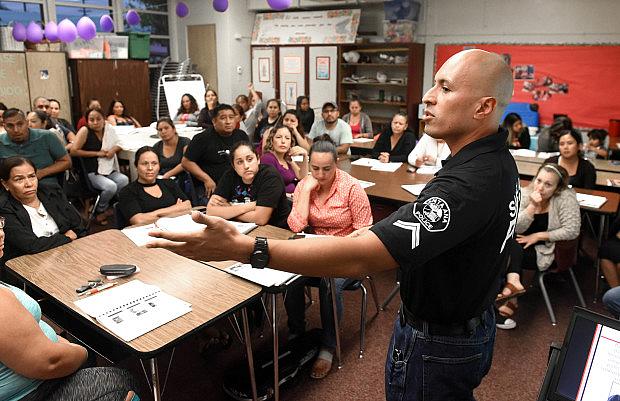

Santa Ana Police Department Corporal Rick Velasquez teaches a session of the department’s Parent Academy which is designed to educate parents on the signs of gang membership. The session was held at Madison Elementary School Santa Ana, CA on Thursday, October 19, 2017. (Photo by Bill Alkofer, Orange County Register/SCNG)

Santa Ana police Cpl. Rick Velasquez asked the room of about 60 parents how many knew a gang member. More than half of the hands shot up.

Many of the parents said they don’t let their children play outside because they live in neighborhoods dominated by gangs and drugs. One mother said she doesn’t go out at night, even if she needs milk or bread. Another said her children worry when she takes a walk, fearing she might get shot.

The personal sharing — at Madison Elementary School in Santa Ana — was part of a 5-week academy, taught in Spanish, designed to educate parents on signs of gang membership and ways they can protect their children from the pull of gang life.

Orange County has an estimated 13,000 documented gang members, with some of the highest numbers reported in recent years in Santa Ana and Anaheim. That’s down from the mid-1990s, when the county was home to an estimated 19,000 gang members and gang-related murders peaked, but it’s still a major problem.

And in Santa Ana a recent uptick in gang shootings and homicides is prompting renewed efforts to address the problem.

The effort is bringing together civic leaders, police, educators, community groups and religious organizations. All are pushing toward the same goals — to curb gang-related crime and help children stay out of gangs and deal with emotional aftermath of the violence in their neighborhoods.

Here’s a look at some of the challenges the effort faces, with comments from researchers and gang experts.

Why do some kids turn to gangs?

The majority of young people join gangs between ages 11 and 15, said James C. Howell, a senior research associate at the National Gang Center, a federally funded agency.

Mental health problems, stress, violence at home, and drug use are all factors that can push people into gang life, Howell said.

Cheryl Maxson, a professor of criminology, law and society at UC Irvine, said gangs emerge from communities affected by poverty, lack of opportunities, institutionalized racism, poor resources in schools, overextended parents and inadequate supervision. That said, she noted that most young males living in such disadvantaged neighborhoods don’t join gangs

“Even in neighborhoods with many gangs, it is estimated that 7 or 8 out of 10 adolescents will not join,” she said.

What makes the difference? Researchers have found at-risk kids who don’t join gangs tend to have so-called “protective factors,” such as safe, healthy, strong and nurturing relationships that can help buffer the effects of violence.

Still, officials say too many are vulnerable to be recruited.

Frank Gonzalez, a mental health therapist, spent 14 years working with minors in Orange County Juvenile Hall. He said many of the kids recruited by gangs were first generation Latinos with immigrant parents who often worked long hours and settled in neighborhoods with histories of gang activity.

A consistent theme, he said, was that recruits often felt both fear and resignation; they saw few options beyond joining a gang. Gonzalez said the thinking boiled down to a simple, “You are (either) with me or against me.”

What’s being done locally to deter children from joining gangs?

The Orange County Gang Reduction Intervention Partnership, or GRIP, is a countywide effort involving law enforcement, educators, faith-based organizations, businesses and community groups. The aim is to prevent at-risk children from associating with or joining gangs and focusing them on a path of education, positive self-esteem and making good choices.

Launched in 2007 at two schools, the program now is offered at 54 school sites from Anaheim to Santa Ana and San Clemente.

“I saw the absolute slaughter of human lives that criminal street violence would cause,” said Tracy Miller, who helped develop and now oversees the district attorney’s gang prevention efforts.

“I saw 14-, 15-, 16-year-olds committing murder. And I thought there needs to be something that we can do to stop this from happening.”

The program centers on improving academics, school attendance and students’ attitudes. It currently links more than 2,000 at-risk students with mentors that include teachers, deputy district attorneys and Big Brothers and Big Sisters.

Fifth-and sixth-grade students at participating schools attend a class intended to help them resist peer-pressure, build self-esteem and become positive leaders.

Students also are invited to soccer camps and taekwondo training. A free trip to an Angel’s game is given to 2,000 students who stay in school and steer clear of gangs.

“Often these kids are not exposed to anything but their two-square-mile neighborhood,” Miller said.

The program seeks to instill hope, Miller said. Specifically, it reinforces the message that with the right choices, students can pursue an education and opportunities that run far beyond gang life.

Ricky, who asked that his full name not be used, is an example of taking an alternate path. He said the Orange neighborhood where he grew up included gang influence, with gang members gathering on corners and shootings a routine part of life. At 13, Ricky says, he was on the verge of getting kicked out of school and jumped into a local gang.

But a GRIP intervention meeting called by the school principal changed the trajectory of his life, he said. The session included his parents, a deputy district attorney, a licensed marriage and family therapist, a case manager, and a representative from the Orange Police Department, said Ricky, now 18.

“All the negative stuff I took out of my life and they actually opened doors and explained to me what was going to happen if I kept on the same path … it was pretty scary.”

His parents began attending parenting classes and marriage counseling and became more strict. “My mom would go to school once a week to get my grades,” he said.

Ricky graduated from high school in May, is working full time and attending community college, with the goal of becoming a physical therapist.

Miller said that’s a key measure of success: At-risk children who graduate from high school without committing a crime and go to college. “We have thousands of kids who have done that,” she said.

Santa Ana’s Parent Academy takes a slightly different approach, focusing in part on educating parents and caretakers about gangs, what to watch for in their children and how to help them resist pressure to join.

The class also is an opportunity for police to build a positive connection with the parents “who are the eyes and ears of the community” and to make sure they report crimes and don’t fear the police, said Velasquez, the Santa Ana police corporal.

How do you break the cycle of multi-generational gangs?

Research shows that helping families establish consistent discipline, diligent parental monitoring and stronger family and mentor relationships is key to helping at-risk children.

Melissa T. Merrick, a behavioral scientist at the Centers for Disease Control says research also shows adults who grew up impoverished, in dangerous neighborhoods or witnessed violence or drug use during childhood are more likely to have children who face similar outcomes.

“We have to care about the whole family system and really work to interrupt this cycle of violence that is so prevalent,” Merrick said.

Breaking that cycle requires, in part, changing what some children are raised to believe is common, acceptable behavior, said Aquil Basheer, who runs the Los Angeles-based Professional Community Intervention Training Institute, which works with communities worldwide to reduce gang violence.

“All they see is marginalized components around them so this is what they buy into,” he said, “You’ve got to bring viable options to the table that will make them want to change where they are at and most importantly you’ve got to give them some rationale as to why they should change.”

What more needs to be done?

Echoing comments of some researchers and federal gang experts, Santa Ana Mayor Pro Tem Michele Martinez, who observed gang activity and drug dealing first hand growing up in the city, said better coordination of neighborhood services by schools, the city and community groups is essential to reaching children and families in need.

“There are a lot of fragmentations,” she said, adding that “has been a big barrier to helping these families.”

Better evaluation of the effectiveness of services provided to at-risk youth and their relatives by nonprofit organizations also is needed, she said.

Steve Kim, executive director of Project Kinship, a Santa Ana-based nonprofit inspired by Los Angeles’ Homeboy Industries, created by Father Gregory Boyle, said the deeper reasons gangs thrive, including poverty, lack of food and clothing and unstable homes, must be addressed. That means doing more to provide education and community programs that can make a difference, he said.

“No kid ever joins a gang because they feel hope,” he said.

Where can families and children turn for help?

The Santa Ana Unified School District – one of the largest in the state and the largest district in Orange County – recently beefed up student and family counseling programs to serve more students struggling with personal and neighborhood problems.

Those efforts include programs aimed at students who have been expelled for behavior, attendance or performance issues or referred by probation officials.

Project Kinship, a non-profit organization, runs group discussions at five district schools and offers a range of counseling, art therapy and other programs to students.

On a recent morning, a handful of students spent part of their day at one of the schools, REACH Academy, participating in what social workers call a restorative circle, where they discuss issues affecting them at school or at home.

“I’ve had students come with horrific stories of gangs, sexual abuse,” said Steven Delgado, a Project Kinship social worker who facilitates the exchanges. Other students have shared the experiences of seeing a parent deported, not having a place to sleep or doing drugs.

“It’s a holistic approach of helping the child heal, helping the family heal and giving them the mental health services that they need,” said Santa Ana Unified School Board Member Valerie Amezcua, who worked at the county probation department for 30 years.

A separate non-profit program, Neutral Ground, serves three district campuses with counseling, mediation and recently launched an after-school program for junior high and high school students. The goal is to ease pressures on at-risk students, including from rival gangs in their communities, and defuse tensions between rival groups.

“We try to keep the streets out of the school so the school is a safe haven,” said Nati Alvarado, a pastor and executive director of Neutral Ground. “Even though they are from different neighborhoods, we get them to a place where they respect each other.”

“A lot of these kids just want to be regular kids,” he said, but they find themselves stuck in communities that can make that difficult.

“We live in the land of the free,” he said. “But they are not free.”

[This story was originally published by The Orange County Register.]