2023 Is San Francisco’s Deadliest Year on Record for Drug Overdoses

The story was originally published in San Francisco Public Press with support from our 2023 Data Fellowship.

Anne Bluethenthal, artistic director of ABD/Sky Watchers, urges people gathered at Civic Center Plaza to open their hearts to those suffering on the streets of San Francisco as she speaks at an annual homeless memorial vigil organized by her group along with the Interfaith Council, San Francisco Night Ministry and the Coalition on Homelessness.

Last Thursday San Francisco’s chief medical examiner released the city’s updated overdose death count — 752 so far — making 2023 the worst year on record for drug-related fatalities.

As fatal overdoses swelled, so did cases involving fentanyl, which was a factor in more than 81% of overdose deaths this year. That statistic is up from 70% in 2022, and 74% in 2021.

Nearly one-third of those people were listed as having no fixed address. Later that day, a crowd gathered at Civic Center Plaza to remember more than 420 who died in the city while experiencing homelessness this year.

At the vigil, some people held electric candles, while others raised some of the 40 banners displaying names of those who had died as participants took turns reading the names and ages of loved ones and friends, as young as 17, each accompanied by a chiming bell.

“There seems to be a fixation on the inconveniences and the material consequences of homelessness, and how it affects the housed rather than a centering of the human being, of the unhoused themselves,” said Benjamin DeShazo-Couchot, director of the San Francisco Night Ministry Care Line. “May we also remember them for living, learning, knowing, hoping, striving seeking, loving, surviving. This is also part of the story that must be known.”

The event, held annually over the past two decades, is organized by the Interfaith Council, the Coalition on Homelessness, the Night Ministry, the Faithful Fools and the arts nonprofit ABD/Skywatchers. Participants spent an hour reading all the names of those who had died, representing more than twice as many as there were last year.

“This gathering every year is a testimony to what is possible,” said Anne Bluethenthal, founder and artistic director of ABD/Skywatchers. “As we stand together this evening, we declare that we will not turn away — not locally, not globally. We will look, we will listen, to all the stories, to all the wailing. We will leave open our tender hearts. We will tell the truth of what we see, what we hear, what we feel.”

Banners display the names of 420 people who died in San Francisco while experiencing homelessness in 2023. People gather at Civic Center Plaza Thursday during an annual homeless memorial vigil organized by the Interfaith Council, San Francisco Night Ministry, ABD/Sky Watchers and the Coalition on Homelessness.

Sylvie Sturm / San Francisco Public Press

Last April, harm reduction advocates warned officials that a police crackdown to arrest people under the influence of drugs, against the advice of health experts, could lead to worse health outcomes. In its 2022 Overdose Prevention Plan, the San Francisco Department of Public Health argued that punitive policies “have not been shown to be effective at reducing overdose deaths, while incarceration is known to significantly increase risk of dying of drug overdose.”

Advocates have urged the city instead to open overdose prevention centers. These would allow drug users to consume under supervision, so they could get immediate help in case of overdose while also offering access to basic hygiene and medical services, food assistance and treatment referrals.

City officials have expressed reluctance to operate such a center, saying it would contravene federal and state laws that make it illegal to “knowingly open, lease, rent, use, or maintain any place, whether permanently or temporarily, for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance.” But the city indicated willingness to support a facility if it were funded and operated by a nongovernmental entity.

Gary McCoy, vice president of policy and public affairs for HealthRight 360, a nonprofit contracted by San Francisco to provide treatment services, announced in October that his organization had raised the funds needed to run an overdose prevention center. He said the organization is still waiting on the Department of Public Health for the go-ahead to open a facility.

In a written response to a Public Press request for comment in October, the Department of Public Health suggested that despite the private funding, opening a center could be a long, arduous process, as “there are a number of complex legal, procurement, location, and community factors that need to be addressed.”

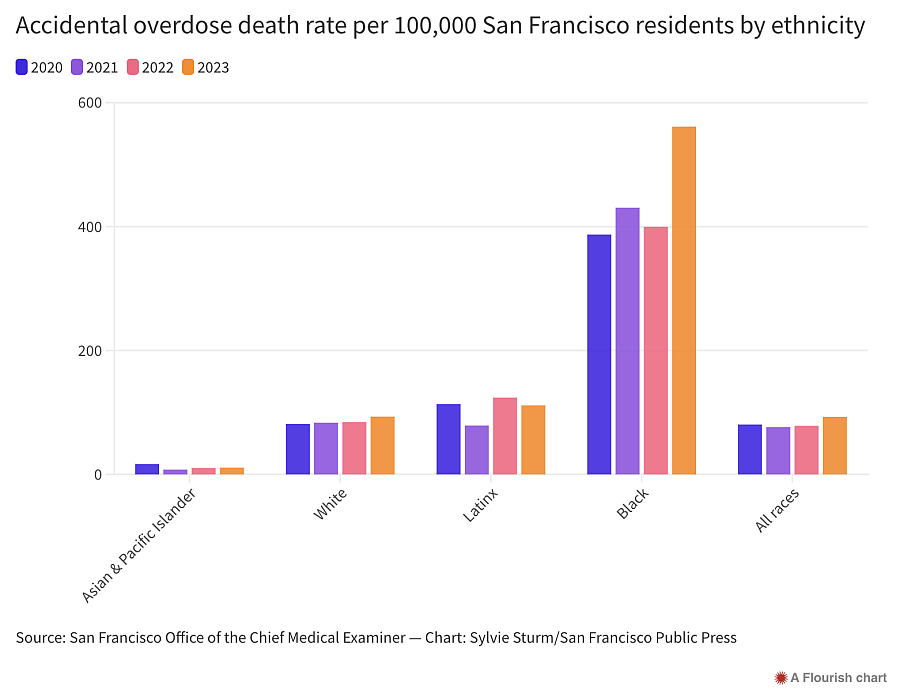

Worsening Trend for Black and Latinx Populations

This is also the deadliest year for overdoses among Black residents, who account for nearly one-third of all drug-related fatalities, despite representing only 6% of the city’s population.

The overdose mortality rate for Black residents is more than five times that of the overall population. In 2020, the previous record-setting year for overdose deaths when 726 people died, one-quarter were Black. In 2021, 642 people died of overdose, and 649 died in 2022.. In both of those years, Black residents accounted for 28% of all drug-related fatalities.

Last Wednesday, the Department of Public Health announced efforts to address these racial disparities with a $2.25 million grant over five years to the Homeless Children’s Network, which will direct funding “to prevent and lessen harmful health outcomes associated with substance use, and to reduce overdose death disparities through innovative, tailored approaches.” The financing came from opioid industry lawsuit settlement money and state Mental Health Services Act funds.

The chief medical examiner’s report for November also indicated a worsening trend for the city’s Latinx population. For the first time since record keeping began, Latinx residents made up a higher percentage of those who died of overdose in one month than Black residents — 28% for Latinx people versus 25% for Black people.

Sylvie Sturm / San Francisco Public Press

Among them was 24-year-old Aurelio Jimenez. His father, also named Aurelio Jimenez, attended the vigil to memorialize his son, even though the younger Jimenez had never been unhoused. Hanging around the father’s neck was a picture of his son as a child posing with a beaming smile in front of a fighter jet.

“It’s hard for us to take as a family because he went to college, he worked at St. Anthony’s, but still, living here, it took him,” Jimenez said, referring to fentanyl.

Jimenez said he had experienced his own struggles with addiction, and because of that, his son had been aware of the dangers of drug use. He added that the trauma of his son’s death caused him briefly to relapse. He is now in rehab.

The younger Jimenez was a health care financial analyst at the St. Anthony Foundation and a corporal in the Marine Corps Reserve. In the comments section of an online fundraiser to pay for funeral services, fellow Marine Manuel Porras, who worked with the younger Jimenez, praised his dedication to service.

“He did not gripe about his duties, but went about them with a smile, helping all who needed it,” Porras wrote. “He spent his life dedicated to the ideals of serving those in need and being a bright spot to his brothers on the hardest days.”

The city’s worsening trend in overdoses in the Latinx community is reflected in statewide statistics. A 2019 study revealed that San Francisco was in the top three counties for opioid-related death rates among Latinos in California. State data show Latinx Californians saw a 68.1% jump from 2020 to 2019, the biggest recent increase among all racial or ethnic groups.