At 28, he died on Berkeley’s streets. His story is part of an epidemic of isolation

This project was originally published in Berkeleyside with support from our 2023 California Health Equity Fellowship.

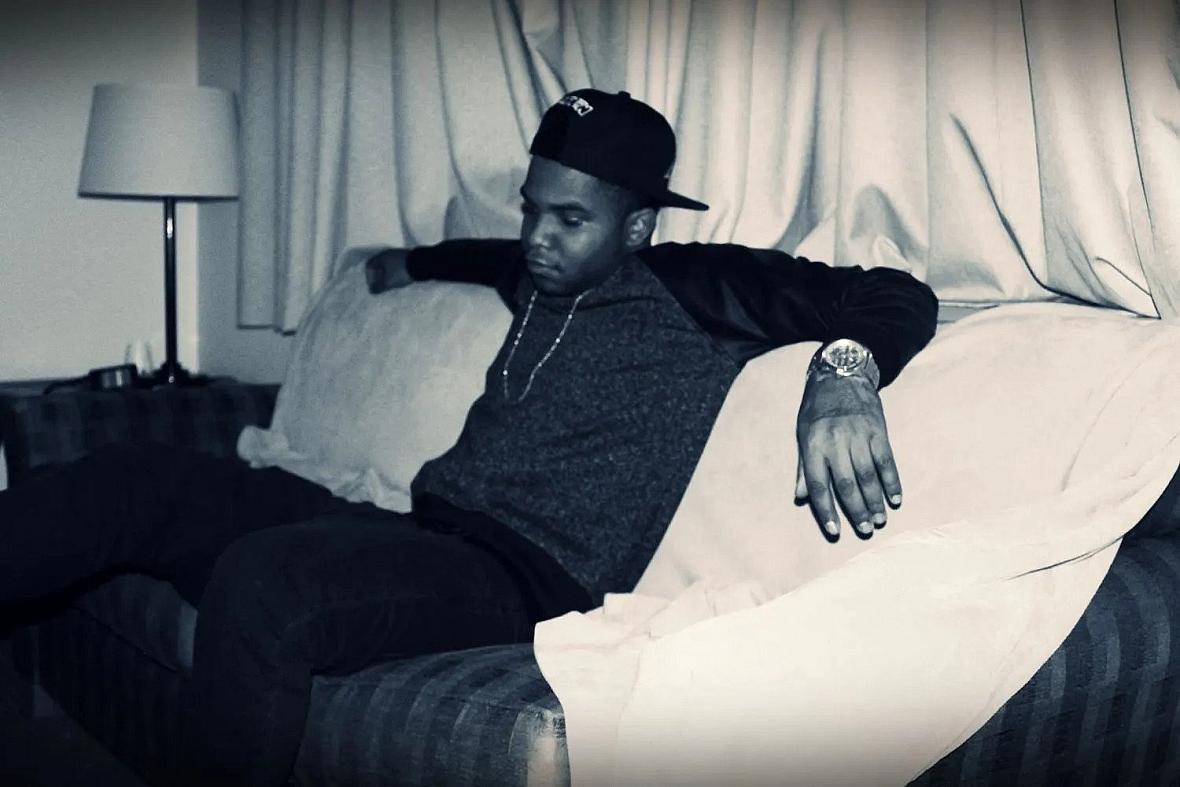

Kiovonni LaRoyce Lyles.

Kimani Okearah

“If we’re gonna talk about hype music from the Bay — it’s gotta be hyphy, not jerk.”

“Nah, you’re not with the new school!”

It was a typical battle in the late aughts between brothers Kiovonni LaRoyce Lyles and Kimani Okearah, then 16 and 19, maternal siblings separated by the foster youth system and reconnected by social media.

Lyles grew up in Richmond and Vallejo, while Okearah was raised a couple of hours east in Placer County. Lyles was into beat-making, jerk rappers (his group was called Alien $qvad), anime, the Golden State Warriors and point guard Baron Davis. Okearah liked the Sacramento Kings, the hyphy music that made the journey to Foresthill, and Midwestern indie rap.

“He was way cooler than me, but he always told me the same thing,” said Okearah, now 33. “He thought of me as this rugged mountain dude. Like, ‘Nah dude, I’m like a Pokémon nerd.’”

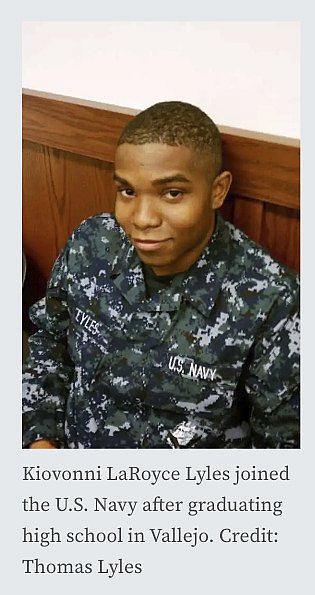

Lyles and Okearah lived together in Sacramento for about eight months after Lyles graduated from Hogan High School in Vallejo and did a stint with the U.S. Navy. Lyles later moved back to the Bay Area in the late 2010s. His family last saw him in 2020, several months before he died at People’s Park in Berkeley the following year.

His exact date of death is unknown, according to the Alameda County coroner’s office, but he was found in a tent on April 10, 2021. His official cause of death is listed as undetermined, but information from toxicology reports indicates that he had methamphetamine and amphetamine in his system when he died.

Between 2018 and 2020, 800 people died on the streets in Alameda County, according to the county report released in the spring. It showed a nearly 90% increase in such deaths over those three years.

Lyles was one of at least four people known to have died in People’s Park between 2020 and 2023, according to witness accounts and the coroner.

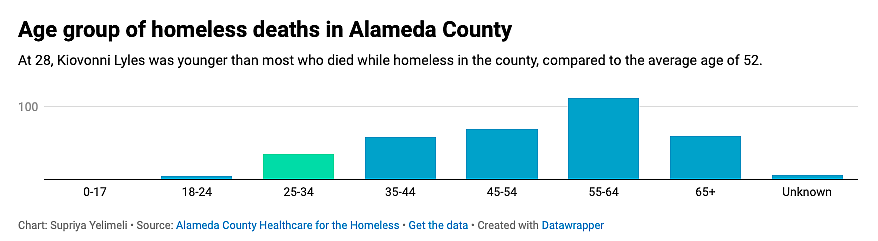

At 28, Lyles was younger than most who died while homeless in the county, compared to the average age of 52. As a Black man, he represented the racial group most likely to die in these circumstances due to layers of systemic racial discrimination in housing and healthcare.

Nearly half of all homeless people in Alameda County are Black, though they make up only 10% of its overall population. And the county’s homeless mortality report found that Black people made up 43% of those who died between 2018 and 2021.

Kiovonni Lyles, born in November 1992, liked to express himself through his music and beatmaking. He experimented with a horror-tinged mood on “Blood Tears,” and rapped “”Finna go to the top … my feet don’t touch the ground,” in a track he shared in 2020.

Credit: Marcus Mitchell

The pandemic exacerbated these health factors for many who died after 2020, like Lyles, though it’s still unclear to what extent. The county’s first report set a precedent for homeless death tracking nationwide; the next one is due in a few months.

Early research shows that pandemic policies successfully prevented incidence and outbreaks of the COVID-19 virus within the homeless population, according to Alameda County health experts. But the broader effects of the pandemic cut vulnerable people off from resources if they weren’t among prioritized groups like older adults and immunocompromised. This may also have played a role in the disproportionate number of homeless people who died of accidental drug overdoses between 2018 and 2021 — now the second leading cause of homeless deaths in Alameda County behind chronic diseases and the leading underlying cause of death, according to the mortality report.

Chart: Supriya YelimeliSource: Alameda County Healthcare for the HomelessGet the dataCreated with Datawrapper

David Modersbach, who led the county’s inaugural study, said the stigma of isolation and loneliness — especially for people sleeping outside, compared to in shelters — was hugely consequential during the pandemic.

“Especially for people like (Lyles), there was more isolation during that time,” Modersbach said. “I think isolation is probably very strongly correlated with increased incidence of death.”

COVID-19 strained families who were already struggling to reach their loved ones on the street

Half-siblings JeCarri, Ledijahnee, Marley, Kiovonni, Monikkia and Kimani at Ledijahnee's son (Raury's) baptism in September 2017.

Credit: JeCarri Jackson

News about Lyles’ death in April 2021, delayed by the time the coroner’s office found him, trickled out slowly to his family members. It was about a week and a half before the entire family — a large group of half-siblings on Lyle’s maternal and paternal sides, as well as his biological mother and father — were aware of what had happened.

The funeral one month later was one of the first times the entire family had gotten together in many years. Okearah said they were shattered. He and others were deeply concerned about Lyles and had become "desperate" to find him in the early months of 2021, but the pandemic prevented them from being able to dedicate the time and money to searching for him.

Okearah said he had initially planned to go streetcrawling in Berkeley and Oakland and ask about his brother by name.

"I thought, how many Kiovonni's can there be?"

“That he went out fighting the demons alone, without knowing he had a whole team behind him … really hurt us."

KIMANI OKEARAH

But his work as a photographer covering the Sacramento Kings became unavailable shortly after lockdown. Without that income, he was unable to get his car repaired to drive to Berkeley from Foresthill, about two and a half hours northeast of the Bay Area, to search for Lyles in the street.

“Everyone was busted up,” said Okearah, when the family learned of his passing. “That he went out fighting the demons alone, without knowing he had a whole team behind him … really hurt us.”

JeCarri Jackson, Lyles’ older half-sister who now lives in Atlanta, flew out with her son to attend his funeral. At the time, she didn’t know that it was the first of many funerals and heavy-hearted travel awaiting her and her family.

Kimani Okearah pictured in Foresthill, California.

Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight

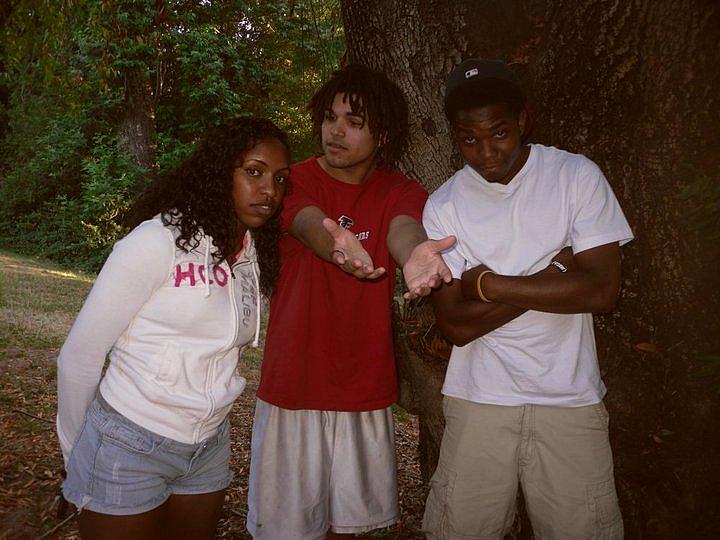

Monikkia, Kimani and Kiovonni in Felton, California in 2010.

Credit: Kimani Okearah

Over the course of the next year, their biological mother, grandmother and two uncles passed away. Some of these deaths resulted from COVID-19 contracted at the funerals. Lyles’ mom, Kim Foster, died of a drug overdose in 2021, something she had struggled with her entire life.

Jackson, 38, said the cumulative loss has left her feeling numb in some moments. At other times, it drains her of all positivity.

“I’m in a twilight zone if that makes sense,” Jackson said. “Grief is grief. I don't even know how to feel some days.”

She said her family was struggling even before the pandemic, and her relationship with Lyles had always been a little strained due to their separation in the foster youth system. Though she was born and raised in Richmond, unknowingly just blocks away from Lyles and his paternal sisters, she left California in 2018 and moved to Atlanta to afford a home and raise her son.

It was a relief to escape the backbreaking affordability crisis in the Bay Area, but she said that after this series of losses, she is now considering returning to be closer to family members.

Lyles’ loss still weighs heavy on her. She remembers him as a good kid who loved music and dreamed of being a producer. He supported her fashion brand and congratulated her on her successes.

“I wish I could’ve did more or knew what was going on or anything, but I was just so caught up in my own life,” she said.

In interviews shortly after Lyles died, people who knew or had met him said he hadn’t lived at People’s Park for long. He died before UC Berkeley made a push one year later to contact homeless residents at the park and register them in the county’s outreach list — Coordinated Entry.

Emerging from COVID, local jurisdictions are strapped for resources to fight isolation for unsheltered homeless people

People’s Park on the day of the homeless count in 2021

. Credit: Supriya Yelimeli

In the two years following Lyles’ death, three more people died while unsheltered at People’s Park. Two men — Tyler Cary, 31, and Malik Djoumi, 32 — died of methamphetamine and fentanyl overdoses on Nov. 4, 2022, and Jan. 3, respectively, according to the coroner’s office. Denise Ann Hatcher, 62, died at the park on March 21; her cause of death is unknown.

Cary left behind a community of friends and colleagues from his time as a Ph.D. candidate at UC Davis. They also said in the days after his death that they wished they could have supported him, and didn’t know he was struggling.

While Berkeley doesn't have a formalized "family reunification" program for homeless residents, Peter Radu, head of the city's homeless response team, said the city's two full-time outreach workers operate on a by-name basis to connect people with family or friends, who may be able to support them. Occasionally, this results in someone connecting with their support network and returning home.

The city's priority is "exits from the street" — or getting people housed.

The bulk of the city and county’s homelessness strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic came from Project Roomkey and Project Homekey, which were designed to house people living on the street who were medically vulnerable, including elderly residents and people with disabilities.

Through these programs, Berkeley converted the Super 8 Motel and Golden Bear Inn into permanent housing with the support of state funding, and has others in the works, including the former Rodeway Inn-turned University Inn.

“We had extraordinary success with that mobilization, where we brought about 3,000 people indoors, picking the most vulnerable people,” Modersbach said. “Of those people, we found out that the whole thing worked. Seventy percent of people who came indoors ended up exiting into housing.”

The county prioritized creating “communities of care” around this time, connecting grassroots homeless advocates with nonprofits and city and county resources.

At the same time, group shelters that formerly accepted walk-ins closed their lists and expanded their hours to prevent outbreaks. Medical care became more challenging to seek out, with a spate of ever-changing rules and limited appointments.

And even with many emergency mobilizations, people like Lyles slipped through the cracks.

Lyles was always a “handle it yourself” kind of guy, his siblings said, and was also influenced by a culture of self-sufficiency in the Navy — despite the PTSD he may have experienced due to his time in the service. There were months when he would fall off the map, typically when he was struggling, but they could usually count on connecting with him on their birthdays, or at a family function.

The pandemic all but vanished these moments of organic connection — chances to check in on family members in person, beyond phone calls and text messages, and extend support where it was possible.

“Isolation and aloneness — the stigma is a really big deal. And it’s a big killer of people,” Modersbach said. “It’s not getting better anecdotally from my point of view, it’s something that we’re all struggling with — how to build connection, meaning, reason for life in our work and relationships.”

Modersbach said people who were already on the brink found themselves increasingly cut off from the resources that could get them back on their feet. Nationwide, homeless men have felt the consequences of this isolation most acutely.

Radu said it's an unfortunate reality of county and federal guidelines that require certain groups to be prioritized, as a result of limited funding.

"It's tough, it's really tough — there's just not enough resources for everyone," Radu said. "When you have limited resources and you're trying to essentially ration them in the best way, whatever decision you make about who is most in need will necessary create winners and losers."

The former Here There encampment on Adeline Street in South Berkeley, where residents were offered motel vouchers before its closure in February 2023.

Credit: Supriya Yelimeli

Moving forward, the city is trying to expand its temporary housing capacities. Radu said it's been a slow process, due to pandemic pitfalls and delays, but congregate shelters (where multiple people share rooms) and other programming are returning to pre-COVID capacity.

According to Josh Jacobs, homeless services coordinator, 417 people who were homeless in Berkeley have moved through the city's temporary housing into apartments, family homes or supportive housing since March 2020.

"Housing first is what works," Radu said. "Step one is get them inside, get them housed, get them in a place where their basic needs are being met, where they don’t have to worry about where they’re going to take their next shower, or where they’re gonna go to the bathroom in 45 minutes."

"If you’re worried about that, if you’re in survival mode, how can you possibly contend with these broader questions of your mental health?"

Lyles's family tried their best to reach him, to get him off the streets. The last time they heard about him during the pandemic, an ex-friend of his said that he was wandering around Alameda County. His parents last saw him around his birthday in November 2020 and offered him a place to stay, but he turned them down.

"Knowing Kiovonni — before he got caught up on anything — he was so self-dependant, so self-reliant. If he got caught up in a problem, he's not gonna want to bring that to anyone's table," Okearah said.

"That's why he didn't ask for help, even though he needed it."