Can $1,000 a month help S.F.’s homeless students succeed? This middle school is finding out.

The story was co-published with El Tecolote as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

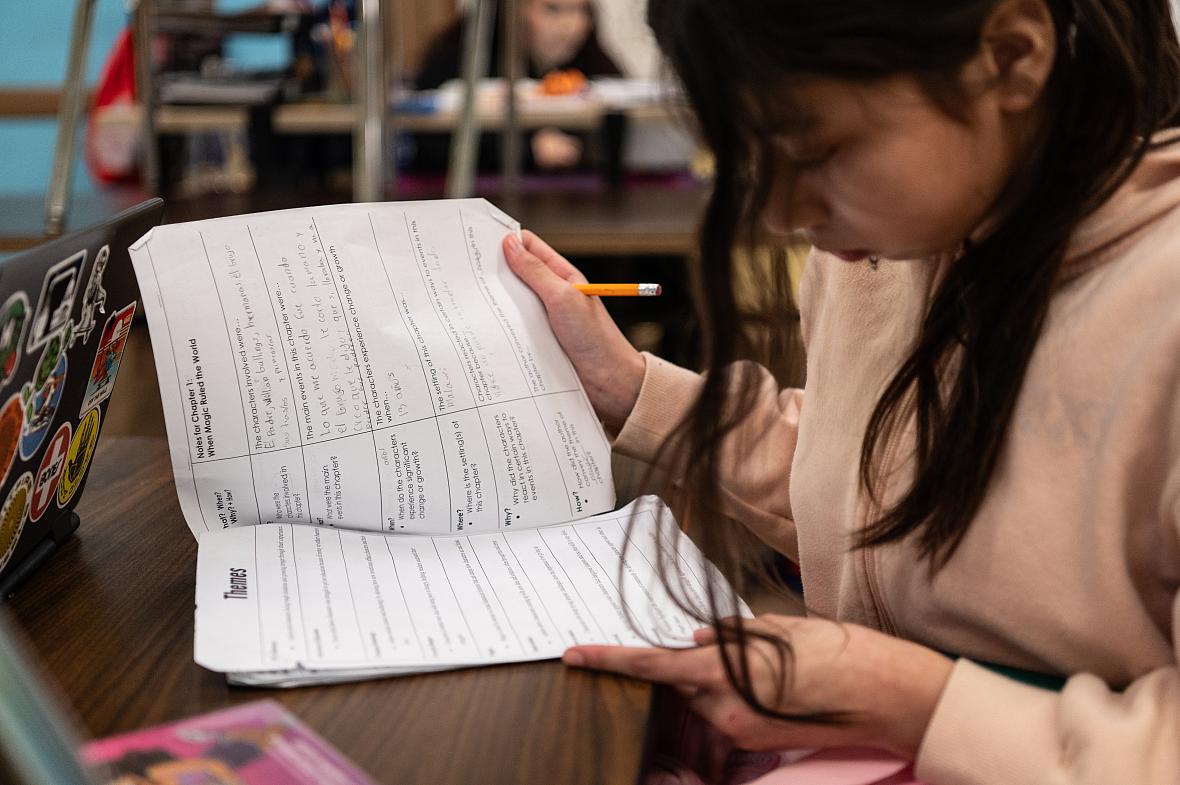

Maria L.’s 12-year-old daughter reviews her English homework after school at Everett Middle School in San Francisco, Calif., on Feb. 13, 2025. Maria, 36, is a recipient of a Guaranteed Basic Income grant program that supports Latino immigrant families with financial assistance and educational resources.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

A year ago, Sadie B.’s daughters struggled to stay awake in class. They were exhausted from spending nights on acquaintances’ couches, moving from one temporary space to another every few months. Sadie, a recently arrived immigrant from Nicaragua, spent her days searching for a full-time job to support her daughters, but without housing, finding stability felt impossible.

Then in September, the girls’ school gave Sadie’s family a lifeline.

Sadie became one of nine parents at Everett Middle School to receive a guaranteed monthly income of $1,000 — part of an experimental program aimed at helping families escape homelessness. With the money, she’s now able to afford a rented room in an apartment for herself and her daughters, who are both enrolled in Everett. And this school year, she says, her daughters are doing better in school, and have high hopes for the future: one wants to become a lawyer, and the other, an engineer.

Sadie’s family is part of a first-of-its-kind pilot program in San Francisco’s public schools to support families facing housing instability. Funded by a city grant, Everett is giving nine unhoused families cash payments every month for three years, hoping that financial stability will improve their students’ mental health and academic performance.

Maria Figueroa, 31, a newcomer site coordinator, opens the door to a classroom at Everett Middle School, where children in San Francisco’s Guaranteed Basic Income program for Latino newcomers do their homework. San Francisco, Calif., Feb. 7, 2025.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Maria Figueroa, 31, a newcomer site coordinator, opens the door to a classroom at Everett Middle School, where children in San Francisco’s Guaranteed Basic Income program for Latino newcomers do their homework. San Francisco, Calif., Feb. 7, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

The program was inspired by the principles of Guaranteed Basic Income (GBI), which have gained traction across the country in recent years as a way to reduce poverty. Unlike traditional aid, which often comes with restrictions, GBI gives people cash directly, trusting them to spend it on what they need most. Studies in recent years have shown that similar programs can improve both financial and mental health — results that Everett is hoping to replicate.

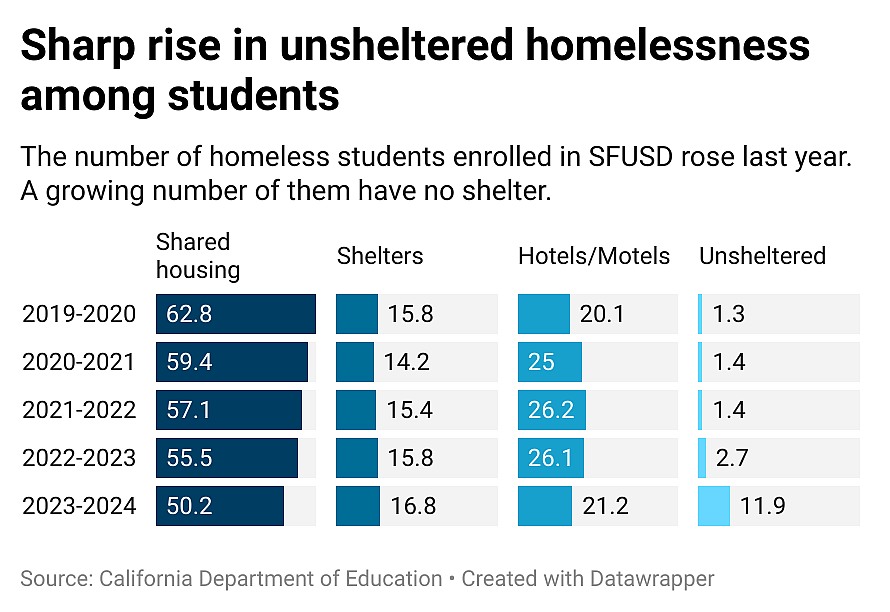

With more than 3,000 SFUSD students reportedly experiencing homelessness last year, and many of them struggling with depression, anxiety and academic difficulties, Everett is one of the many schools stepping in to help their students succeed beyond the classroom.

An unconventional solution to a deeply rooted problem

Located in the heart of the Mission District, Everett has seen a surge in student homelessness over the past two years. Last year, the number of students experiencing homelessness nearly doubled from 55 to 102, making up 17.8% of the school’s student body, according to data from the California Department of Education. School staff estimate that this year that number is likely to rise above 20%, since some families don’t formally report their housing status.

Everett’s homeless students live with friends and acquaintances, in temporary shelters, in hotel rooms or on the streets altogether. They’re among the working-class families and newly arrived immigrants who struggle to find sustainable jobs and affordable housing.

Social worker Bridget Early, who has spent 17 years working at Everett, says she has witnessed how deeply homelessness affects these students. Many struggle with attendance, she said, and when they do make it to class, they sometimes act out or exhibit depressive symptoms.

“When you're living in poverty day in and day out… you're engaged constantly in fight or flight survival mode,” said Early. “At some point your brain functions the same as if you haven't slept at all.”

Over the years, she’s connected homeless students to therapists, and other district-wide resources like tutoring and free backpacks, designed to support SFUSD’s most vulnerable. But while helpful, Early said, these interventions don’t “get to the root of the problem,”

Bridget Early, a social worker and counselor at Everett Middle School for 17 years, sits in her office on campus in San Francisco, Calif., on Feb. 7, 2025. Early spearheaded the first Guaranteed Basic Income program for Latino newcomer students and their families in the city.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Bridget Early, a social worker and counselor at Everett Middle School for 17 years, sits in her office on campus in San Francisco, Calif., on Feb. 7, 2025. Early spearheaded the first Guaranteed Basic Income program for Latino newcomer students and their families in the city. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Some researchers have found that the stress of not being able to meet one’s basic needs can even change the way people think, a concept known as bandwidth poverty. Studies show that when people must devote all their energy to immediate needs — like food, shelter and survival — they struggle to plan ahead.

To Early, this research suggested that reducing financial stress could be the key to improving student success and wellbeing.

“What we want to see is okay, you're given an extra $1,000 dollars, will your quality of life improve?” she said. “Will [you be] able to function better in the world?”

When San Francisco’s Student Success Fund opened applications last year, Early pitched the idea of giving families unconditional cash payments. She secured $250,000 for Everett every year, enough to support ten sixth grader families until they graduate from middle school. The nine families that fit the school’s criteria were all Latinx immigrants, Early said, and the school is keeping one spot open in case another family in need enrolls later in the year.

Maria Figueroa., 31, a Latinx newcomer site coordinator with Good Samaritan, helps students with their homework at Everett Middle School in San Francisco, Calif., on Feb. 7, 2025.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Maria Figueroa., 31, a Latinx newcomer site coordinator with Good Samaritan, helps students with their homework at Everett Middle School in San Francisco, Calif., on Feb. 7, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

With guidance from Stanford’s Economic Inclusion Lab, Early designed the GBI program to also provide mandatory personal development workshops for parents, weekly one-on-one check ups with the participating students, a food bank and a thrift store. Early and her team are also tracking whether families’ quality of life improves over the next three years through biannual surveys.

“It might not still be enough. I don't know,” Early said. “But I wanted to try something different and not keep on doing the same thing, assuming that it would change when I know it hasn't changed.

Families say they can start to “bring other things to the surface”

Despite the program’s early stage, many participating parents say the cash payments have already started alleviating pressures in their day-to-day lives.

Emily L., a Venezuelan mother of three, said the money came “like a blessing.”Her family arrived in San Francisco in January of last year, seeking asylum, and she has been raising her children with her husband in a private shelter room.

“We only had my husband’s income as a delivery driver, which isn’t much,” she said. “This has given me the opportunity to bring other things to the surface. I can pay for my [asylum] lawyer, and other small things.”

Emily L., 29, a recipient of the Guaranteed Basic Income program, stands beside a flowering bush at Dolores Park in San Francisco, Calif., on Feb. 12, 2025. “I’ve always loved flowers,” she said. “One day, I’m going to have my own garden with flowers.”

Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Emily L., 29, a recipient of the Guaranteed Basic Income program, stands beside a flowering bush at Dolores Park in San Francisco, Calif., on Feb. 12, 2025. “I’ve always loved flowers,” she said. “One day, I’m going to have my own garden with flowers.” Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Emily said her eleven-year-old son has offered to stop studying to help care for his two youngest sisters. But Everett’s grant, she said, also helps her reassure him that what he’s supposed to be right now is a student.

“It’s something that breaks you, because he’s a kid,” she said.

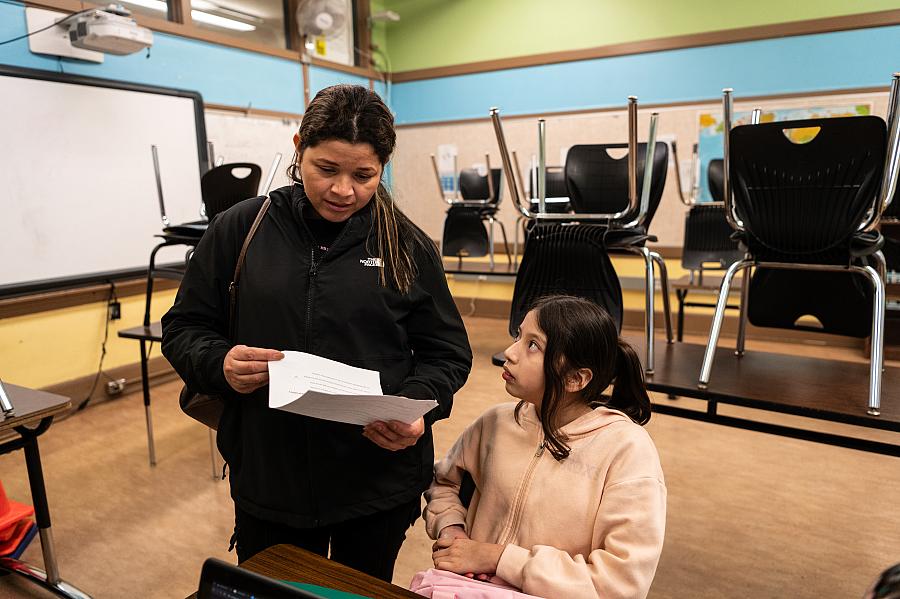

For Maria L., a Nicaraguan single mother who has lived in San Francisco for three years, the extra money allows her to work part-time as a cleaner while still having the time to take care of her daughter, and pick her up from after-school programs where she can work on her homework.

“I see my daughter and she’s different,” said Maria, who also uses parts of the funds to pay rent and her daughter's dental appointments and medicines for when she catches a cold. “She’s more excited for classes, she feels more motivated because she’s supported by the school too.”

Maria L, 36, checks her 12-year-old daughter’s English homework after school at Everett Middle School. Maria and her daughter crossed the Rio Grande by foot a few years ago, fleeing political violence in Nicaragua. Maria's daughter hopes to be able to go to college. Currently, English is her most difficult class, the 12-year-old says, but is learning the language very fast.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Maria L, 36, checks her 12-year-old daughter’s English homework after school at Everett Middle School. Maria and her daughter crossed the Rio Grande by foot a few years ago, fleeing political violence in Nicaragua. Maria's daughter hopes to be able to go to college. Currently, English is her most difficult class, the 12-year-old says, but is learning the language very fast. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

A future in limbo: Can San Francisco expand the program?

Everett’s staff say they are already seeing improved attendance and parent engagement from the participating families. And as word of the program spreads, SFUSD officials are also watching closely to see how much the program changes their lives.

Among them is District Superintendent Maria Su, who is hopeful that the program will empower their students to “fully engage with their education.”

Meanwhile, Matt Alexander, a Board of Education commissioner and one of the authors of the Student Success Fund, said he thinks the program should be expanded.

"You can give all the therapy in the world,” Alexander told El Tecolote. “But really, what families need is some economic stability."

Emily L., 29, (Second from left) a recipient of the Guaranteed Basic Income program, sits in on a community meeting for homeless immigrant families inside the Faith in Action office in San Francisco, Calif., on Jan. 28, 2025.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

(Second from left) Emily L., 29, a recipient of the Guaranteed Basic Income program, sits in on a community meeting for homeless immigrant families inside the Faith in Action office in San Francisco, Calif., on Jan. 28, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Still, funding remains a major roadblock.

The Student Success Fund, created through taxpayer-approved funding in the 2022 election, is designed to support students’ academic and socio-emotional wellbeing for the next 15 years. Everett secured one of the fund’s first-round of implementation grants, which covers three years of funding for its GBI program, with a potential two-year extension.The grant, however, is only enough to support 10 families out of the hundreds across the city that continue facing homelessness.

The fund is tentatively set to grow to $45 million in July, potentially allowing other schools to replicate Everett’s GBI model in the next academic year. But San Francisco’s massive budget deficit and SFUSD planned layoffs to address its $113 million shortfall could limit the expansion of the fund.

Additionally, even with financial support, life in San Francisco remains difficult for participating families. The average cost of renting a studio apartment in the city is $2,100 — more than double what families receive in their monthly stipends. Meanwhile, new city policy and federal immigration crackdowns put many at risk of displacement, threatening the fragile stability that they’ve managed to find.

Emily says the stress of it all gives her anxiety attacks that she talks through with her shelter’s case managers. “I feel too awful about everything that’s happening with migration, with housing,” she said. “And then we just got another eviction notice.”

Although she can now afford to buy food and clothes for her family, Sonia H., another program participant whose family is currently staying in a family shelter, said she experiences bouts of depression. Her teenage son often refuses to eat, she said, and her sixth-grade daughter struggles with the shelter’s strict rules.

Sonia H., 33, a recipient of the Guaranteed Basic Income program, stands for a portrait at Dolores Park. A newcomer from El Salvador, Sonia endured a traumatic migration journey with her children as they crossed the Rio Grande.

Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Sonia H., 33, a recipient of the Guaranteed Basic Income program, stands for a portrait at Dolores Park. A newcomer from El Salvador, Sonia endured a traumatic migration journey with her children as they crossed the Rio Grande. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

“She doesn’t have any privacy,” Sonia said. “They turn on the lights at 6 a.m. and it wakes her up, so she's often irritable and in a bad mood.”

Still, families remain hopeful that three years of guaranteed income will be the additional push they need to get back on their feet, and to grow their own support net.

Now that her two daughters are doing well in school and she can afford a room, Sadie is thinking about what comes next.

“I used to cry so much,” Sadie said. “I couldn’t talk about my life the way I do now, without tears, thinking about all the things that had happened to me. But I think now I can breathe a bit more easily.”

Sadie B., says that after receiving her first payment, the first thing she bought was a bed for her daughters. “Before the program, it was very hard—I almost moved back to Nicaragua.”

Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Sadie B., says that after receiving her first payment, the first thing she bought was a bed for her daughters. “Before the program, it was very hard—I almost moved back to Nicaragua.” Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Sadie is using part of her stipend to start selling Nicaraguan food to people she meets at work. Eventually, she wants to buy a food cart to sell her homemade dishes in the city, hoping she can earn enough to rent a studio for the family — a space of their own.

“I’ve already progressed so much,” Sadie told El Tecolote. “Imagine how much could happen by the time the year ends.”

To protect their privacy, El Tecolote has identified immigrant families in this story using only their first names and last initials.

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of "Healing California", a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.