Access to food a problem throughout Riverside, San Bernardino counties

This story was originally published in Daily Bulletin with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

When Jeanette McCulloch wants to make a quick grocery run, her choices are limited.

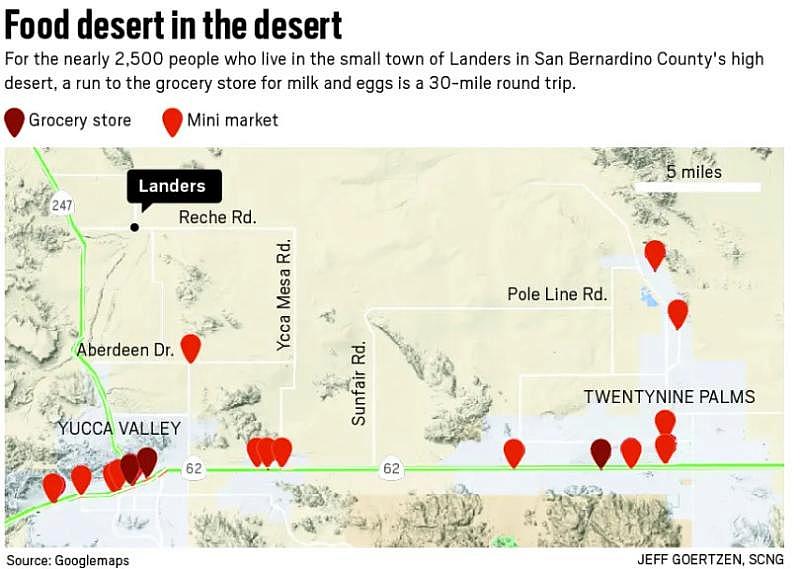

There are a couple of corner stores in Landers, but affordable and healthy options are elusive in this unincorporated community in the Mojave Desert. The closest market with a full produce section is about 13 miles away.

Landers, home to about 2,500 people, is considered a food desert, a community where people live more than a mile from a supermarket in urban areas, or more than 10 miles in rural areas, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A product of this lack of access to food is what’s known as food insecurity — defined by the USDA as being unable to put adequate healthy food on the table at times for all members of a household.

In 2019, the latest year data is available, more than 13% of San Bernardino and Riverside county residents were considered food insecure.

And, according to data published in 2017 by San Bernardino County, Landers is one of 32 food deserts identified in the county as some of the poorest and furthest away from grocery stores. Similar data was not immediately available for Riverside County.

Living in a food desert, coupled with record inflation in recent months, means residents in these communities face some of the toughest obstacles in accessing affordable and healthy food.

Going the distance

The entire High Desert represents the largest concentration of high poverty/low access food deserts in San Bernardino County, areas where 50% or more of the population earns less than 185% of the federal poverty level, or no more than $51,338 for a family of four.

Out of 32 food deserts across San Bernardino County, 19 are in the High Desert, according to county data.

Living in an isolated area, 30-mile round-trip grocery runs are a part of life, 59-year-old McCulloch said.

The nearest large-scale markets are located on a main commercial strip on Highway 62, about 15 miles from McCulloch’s home.

Recently, the long drives have taken a back seat to economic realities at the grocery store.

A 9.2% inflation rate in Riverside and San Bernardino counties this summer, the second highest in the nation, raised the price of just about everything.

When McCulloch visits the nearest Vons in Yucca Valley, about 14 miles from her home, higher priced organic food is off limits and if an item isn’t on sale, it’s not going in her shopping cart.

“I always had a strict shopping list that I had to stick to,” said McCulloch. “But now, with prices rising, that list is a lot shorter.”

Like many others in Landers and throughout the Inland Empire, McCulloch supplements her grocery trips with visits to local food distributions.

At a recent distribution provided by FIND Food Bank at Copper Mountain College in Joshua Tree, more than 30 cars were in line by 7 a.m. Residents who traveled as many as 50 miles waited to accept free food. McCulloch was at the front of the line.

A line of more than 30 cars await a food distribution event to begin at Copper Mountain College in Joshua Tree on Aug. 2, 2022. For many in line, record high inflation and limited access to fresh produce has forced them to seek help. (Photo by Javier Rojas/Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/ SCNG)

Since the pandemic in March 2020 disrupted food deliveries to stores, food distributions have become one of the few places McCulloch can get fresh tomatoes and chicken.

She also picks up food for neighbors, mostly older people who can’t make the trip.

“They rely on this as much as I do,” McCulloch said. “When you live out here, it can get really hard.”

It’s not just those living in rural areas who face barriers to grocery stores. Sometimes the need is hidden in plain sight.

In Riverside, the store closest to Roberta Dalton, 64, closed in July. What would typically be a minor inconvenience for some is a hardship for Dalton.

Making the 6-mile trip across town to the next-closest Stater Bros. Market isn’t easy. His car isn’t reliable and with high gas prices, Dalton said, his fixed income “is being pushed to the limit.”

While there are convenience and discount stores closer to Dalton, they don’t provide fresh meal options, he said. A nearby church’s food pantry has become a “savior” for his five-person household, he said.

“I’d like to be able to go walk to the store but I just can’t do that anymore,” he said. “Life just feels like it’s getting harder for us.”

Food deserts overlooked

Grocery stores typically operate on slim margins and, considering market changes and labor supply issues that can easily put them out of business, there are fewer incentives to expand in underserved areas, according to Healthy Food Access, a national think-tank producing policies to improve food access.

This leaves some neighborhoods — particularly those with lower income levels or those that are predominantly communities of color, research shows — without dependable grocery outlets. The supermarkets that remain in such neighborhoods are unlikely to sell affordable and nutritious food.

A 2015 Associated Press analysis found that major grocers overwhelmingly avoid food deserts rather than try to turn a profit in high-poverty areas. While grocers opened 2,434 stores between 2011 and early 2015, only 10% were in areas considered food deserts. These new stores served one in 10 residents living in a food desert nationally, AP found.

In San Bernardino County, residents identified access to healthy food and grocery stores as the resource most lacking in their communities, according to a 2020 Community Indicators Report that surveyed 1,697 individuals.

Similarly in Riverside County, stakeholders and residents said increasing access to and consumption of affordable healthy food was one of their highest priorities, according to the 2019 Community Health Assessment.

A lack of grocery stores and the availability of fresh, affordable food is associated with greater consumption of higher calorie and less nutritious food, leading to an increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cancer and other chronic diseases, according to the San Bernardino County report.

One solution to food deserts in the Inland Empire may come in the form of state and federal financial incentives to build new supermarkets and placing healthier eating alternatives in corner stores.

Those ideas aren’t new. In 2011, California passed legislation, the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, which was aimed at increasing the number of grocery stores in urban and rural areas, although the program hasn’t been funded in recent years.

Over the past decade, the idea has gained traction outside California — Iowa, Idaho and North Dakota have already seen progress in the number of residents accessing supermarkets by offering subsidies or restructuring zoning policies to incentivize development in low-access areas.

Most recently, Missouri legislators passed a bill in 2021 that offers tax credits to encourage grocery store construction in food deserts.

In California, there is hope. The Department of Food and Agriculture in 2019 introduced the Healthy Refrigeration Grant Program, which funds refrigeration units stocked with produce, dairy, meat and more in corner stores, small businesses, and food donation programs.

In two rounds of approximately $4.5 million in grants funded since the program’s launch, however, none have been awarded to stores or organizations in Riverside and San Bernardino counties. A new round of grant funding request proposals is expected in December.

Spotlight on solutions

The pandemic put a spotlight on the presence of food deserts and the need for creative programs that get food to residents who face the most barriers to grocery stores.

Feeding America Riverside | San Bernardino has provided meals to over 14,300 households across the two counties since March 2020 under its Homebound Emergency Relief Outreach (HERO) program. This year, the food bank reported, it had already reached 3,418 households through August.

The in-demand program was created during the pandemic to assist those whose ability to shop for food is restricted by lack of financial resources or health problems. The program is supported through HERO and Feeding America staff, volunteers and DoorDash food-delivery drivers.

Many recipients tend to be older and live in rural areas where driving is necessary to get around, according to Emily Saunders, HERO program coordinator.

On one HERO delivery trip this summer, Saunders made three stops to households throughout San Bernardino County. All of the households were located more than a mile from a grocery store, she said.

A trailer park heaped with junk and debris greeted her at her first stop in the city of San Bernardino.

Three shirtless toddlers played in grass nearby while Saunders waited for someone to answer the door. After a few knocks and phone calls, she left the box of produce and canned goods on the doorstep.

Next, Saunders drove 6 miles east to a senior living complex in Highland where many residents have fixed incomes and can’t make weekly trips to grocery stores, instead relying on food benefits and services like the HERO program.

Her final stop was a home in Mentone, an unincorporated area east of Redlands, where liquor and convenience stores overrun grocery options.

“You see how bad the need is when you make these deliveries,” Saunders said. “Everyone has a different story but same problem — access to food.”

San Bernardino and Riverside counties don’t have far to look for possible solutions to the problem — in neighboring Los Angeles County, residents in Pomona have also long faced barriers to accessing affordable and healthy food.

Customers browse through some of the vegetables and herbs grown at the the Lopez Urban Farm during the of launch of the daily farmers market, Bodega Comunitaria, in Pomona on Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2022. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Pomona artist Joeded Walsh paints a mural on the side of the food pantry during the launch of the daily farmers market, Bodega Comunitaria, at the Lopez Urban Farm in Pomona on Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2022. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Stephen Yorba, Executive Director of Lopez Urban Farms, speaks to those gathered during the launch of the daily farmers market, Bodega Comunitaria, at the Lopez Urban Farm in Pomona on Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2022. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Food and other items are available to those in need on a pay as much as you can basis during the launch of the daily farmers market, Bodega Comunitaria, at the Lopez Urban Farm in Pomona on Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2022. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Vegetables grow in the late afternoon sun at the Lopez Urban Farm in Pomona on Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2022. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

Grassroots organizers like Bianca Ustrell-Friend, 33, saw how lack of food access affected her community and took matters into her own hands, working with others to launch the Pomona Community Fridge, a volunteer-driven program that provides free food from a small standalone refrigerator, while also shuffling a mobile pantry throughout town.

Such mutual-aid projects projects were a “natural response as many in the community lost jobs and income,” leaving little money for food, Ustrell-Friend said.

“It’s our belief that access to healthy food shouldn’t be a privilege, it should be a right,” she said.

While the community fridge was finding its footing, Lopez Urban Farm, a community-based collective, sprouted up on a 2 ½-acre lot near Lopez Elementary School in Pomona. The garden is also located in the middle of a food desert, where neighborhood donut shops and corner stores outnumber supermarkets.

Led by lead farmer and Executive Director Stephen Yorba, the farm transformed a once-vacant lot into a place families can learn to grow their own produce, compost and most importantly, receive fresh food — no questions asked.

Stephen Yorba, executive director of Lopez Urban Farms, speaks to those gathered during the launch of the daily farmers market, Bodega Comunitaria, at the Lopez Urban Farm in Pomona on Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2022. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

In August, Ustrell-Friend and Yorba teamed up to launch Bodega Comunitaria, a pay-what-you-can, take-what-you-need farmers market open daily.

The project aims to meet the needs of an estimated 3,000 unhoused Pomona Unified School District students and their families, as well as the community at large.

All produce sold is fresh and grown locally at Buena Vista Community Garden, Esperanza Community Farm and Lopez Urban Farm — all of which are located within a couple miles of each other.

Along with produce, shoppers can find pantry items, hygiene kits, school supplies, books, sack lunches, preserved foods, and a seed exchange.

While community gardens and fridges aren’t new to the Inland Empire, the pay-what-you-can, take-what-you-need farmers market model is something that Ustrell-Friend said she hasn’t seen anywhere else.

Customers Maria Martinez and her niece Isabella Acosta browse through some of the vegetables and herbs grown at the the Lopez Urban Farm during the launch of the daily farmers market, Bodega Comunitaria, in Pomona on Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2022. (Photo by Will Lester, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/SCNG)

The farmers market represents a “breakthrough” in a period when struggling households will be able to use “their money towards other things and not have to worry about how they’re gonna get their next meal,” Ustrell-Friend said.

Community gardens, fridges and pantries are worthy attempts to help residents who live in food deserts, but they are mostly stopgap efforts unable to repair the larger, systemic problems, according to Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, a U.S. economist and professor at Northwestern University.

What’s needed, she said, are “long-lasting solutions will have to come with policy changes at the federal and state level.

“Having better paying jobs, a thriving economy, wage growth and expanding the social safety net benefits are a start,” she added, and all were a topic of conversation at the White House conference on Hunger, Nutrition and Health in late September, only the second such conference since 1969.

There, President Joe Biden unveiled a national strategy for ending hunger and increasing healthy eating and physical activity by 2030.

Proposed policy changes include expansion of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, broadening free meals in schools and extending summer meal benefits to more children. All of those changes would still require congressional approval.

Schanzenbach is “cautiously optimistic,” however, that recent discussions on food access will help continue bringing the issue to the forefront.

“In 2020, we were not talking about what would it look like to eliminate hunger in the United States,” Schanzenbach said. “But now, people are starting to look at ways to really solve this, that should give us all some hope.”