Hunger grows as inflation spikes in Riverside, San Bernardino counties

This story was originally published in Daily Bulletin with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

A volunteer packages peaches during a food distribution at Vida Life Ministries in Bloomington on July 16, 2022.

(Photo by Javier Rojas/Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/ SCNG)

The line is 20 cars long when Jesus Zavala arrives at 6 a.m. He’s already late.

His black 2011 Toyota 4Runner is parked in a growing queue of cars that snakes down four blocks in Bloomington where the roads are lined by dusty, unpaved sidewalks. He puts up a blue sunshade and closes his eyes.

For the next three hours, Zavala and his mother, Rosa, wait for food to help fill the empty fridge in their Fontana home.

Like many families in the sprawling Inland Empire, the Zavalas feel the pressure record inflation this summer has put on their wallets over the past year. With food prices up about 11% overall, many are turning to food distributions for assistance.

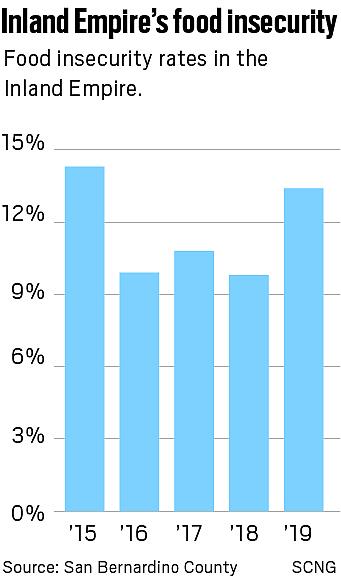

But food insecurity was a problem in Riverside and San Bernardino counties before inflation spiked, with the counties reporting more than 13% of residents did not have enough to eat in 2019, up from a low of 9.9% three years earlier.

At a Vida Life Ministries food distribution in Bloomington, the Zavalas sleep in their car to pass time. It’s summer and by 8 a.m. with the temperature climbing to the mid-80s, the mother and son turn on the A/C to keep cool.

For the next hour, they inch closer and closer to the pallets of spinach, tomatoes and bags of Foster Farms frozen chicken that volunteers pack into trunk after trunk. By 9:30 a.m., their trunk is full and the Zavalas head home.

This has been the their Saturday morning ritual for two months.

“It’s worth it and it means a lot since we’re low income,” 21-year-old Jesus Zavala says.

With his dad the only family member currently employed, Zavala is actively looking for work to help support the six-person household that includes his parents, brothers and sisters.

“We have to try to just make ends meet,” he says. “There’s not really a choice.”

More than 50 cars line up for a food distribution event at Vida Life Ministries in Bloomington, California on July 16, 2022. Many wait more than two hours in their vehicles to receive aid. (Photo by Javier Rojas/Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/ SCNG)

Growing need

In 2019, the latest year for which data is available, San Bernardino County reported that 13.4% of residents in the Inland Empire were considered food insecure, defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as unable to put adequate healthy food on the table at times for all members of a household. In comparison, 9.9% of California residents faced food insecurities that year, as did 10.4% of individuals nationally, according to data collected by the USDA.

Previously, the Inland region’s food insecurity rate had been on a downward trend. After a high of 14.3% in 2015, the rate dropped to 9.9% the following year and hovered there until it spiked again in 2019, according to San Bernardino County.

While figures for 2020 and 2021 are not yet available, food insecurity regionally has showed no signs of slowing down, with applications for the state’s food-assistance program increasing each year since the pandemic began.

Then, inflation reared its head.

In Riverside and San Bernardino counties this past July, the inflation rate reached 9.2%, second highest in the nation. Prices at grocery stores soared as well, with the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting the cost of food in the region increased 11.4% in a 12-month period. Essential items such as bread and eggs jumped in price by 18.5% and 11.2%, respectively, over the past year.

Carlos Medina, CEO at Vida Life Ministries, which has for the past decade dedicated itself to feeding families in need, said his organization sees the impacts of inflation weekly.

“If we didn’t stop giving food at 11 a.m., the lines would go on all day,” he said.

Since January 2022, he added, the church’s weekly food distribution has quadrupled. Each week, the church sees 20 new families. For many, it’s their first time at a food distribution event, underscoring inflation’s widespread impact on the region.

“People are coming from Victorville, Riverside, anywhere in the I.E., you name it,” Medina said. “People need food right now.”

He estimates the church now gives away $150 to $200 in groceries to at least 200 households every week.

Rising costs

Before inflation increased, the pandemic played a factor in rising prices at grocery stores due to labor shortages and higher costs for distribution. As the costs to produce, cultivate and deliver food spiked, those charges trickled down to consumers.

This year, the upward trend in food prices was exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, affecting global supply chains in the process.

Meanwhile, the Inland Empire has experienced significant growth over the past year, spurred in part by a pandemic-related trend that saw people moving away from larger population hubs in Los Angeles and Orange counties to smaller communities with lower housing costs such as Beaumont and Lake Elsinore in Riverside County and Victorville in San Bernardino County.

Now home to 4.6 million people, the Inland Empire is one of the nation’s fastest growing areas. The latest U.S. Census Bureau data shows the two-county region added 47,601 people in the year that ended July 2021, the fifth-largest gain among the country’s 50 largest metro areas.

This migration east has spurred higher demand for goods and services in the region, where there’s been a spike in applications for benefits from CalFresh, the state’s food assistance program for those who meet federal income eligibility guidelines.

Between January and June 2022, San Bernardino County received 104,978 CalFresh applications, making it likely the county will top the 195,716 applications it processed in 2021. Riverside County received 192,881 applications in the fiscal year that ended in June, eclipsing the previous year’s total of 149,504.

During the pandemic, the federal government bolstered food assistance, adding emergency monthly allotments. This meant a four-person household received $835, up from $680 prior to March 2020.

The substantial increases in benefits, however, were mostly eroded by inflation’s impact on grocery prices in recent months.

Cutting back

While long lines of cars at food distributions were a common sight during the onset of the pandemic, those waiting in lines today are being hit with various economic factors attributed to inflation.

Average income and employment numbers have improved since 2020, but “some U.S. households continue to face difficulties obtaining adequate food, particularly in the face of increasing food prices,” according to a USDA report.

In a poll conducted by Southern California News Group, 84% of 25 respondents said they recently worried about not being able to afford groceries. Meanwhile, 60% wrote they don’t get enough healthy food for their household.

With inflation driving up the cost of living, one of the first places people start looking to scale back is their pantries, said Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, a U.S. economist and professor at Northwestern University.

“One of the first things people will do is cut back on the nutritional quality and variety of their food,” Schanzenbach said. “For so many families, the only really variable expenses they have is their grocery bill.”

This means “tough decisions,” she said, for families just getting by, especially those with young children, many of them sacrificing healthier foods for cheaper and likely unhealthier alternatives. This can potentially have lasting adverse impacts to a young person’s overall health and risk of chronic illnesses such as asthma and anemia

According to a food insecurity study published in 2015, compared to children in food-secure households, children in food-insecure households had two to three times higher odds of having anemia and two times higher odds of being in fair or poor health, depending on the age of the child.

“It’s unconscionable to think about kids, especially in those first couple years of life, not getting enough food, especially when it can harm them in the long term,” Schanzenbach said.

But it’s nonetheless a common story, according to Kenneth Martinez, principal in the Community Engagement Office for San Bernardino City Unified School District.

“The mom working three jobs, the kid going to sleep hungry,” Martinez said, “you hear it all the time.”

More than 16% of the school district’s households live below the federal poverty line, or less than $27,750 for a family of four, according to U.S. census data.

In response to the needs of its students, SBCUSD expanded its efforts over the past few years to tackle food insecurity.

The Community Pantry in Hemet has become a source of food aid for many in the community. With inflation rising in 2022, visitors say without the pantry they would not have enough food for their households. (Photo by Javier Rojas/Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/ SCNG)

Since 2018, the district has offered food distributions for families at various campuses each month. Recently, the long lines commonly seen in the early days of the pandemic have returned, Martinez said, as food prices continue to rise.

At Riverside Unified School District, meanwhile, more than 7.4 million meals were served to 32,000 children over the course of the pandemic, according to district spokesperson Diana Meza. A slew of other supplemental food programs have also been introduced to feed hungry students.

“Bottom line, a child has a hard time learning if they are hungry,” Martinez said. “We as educators can’t stand by and do nothing.”

The impact of inflation on food prices extends beyond schools and into communities, Schanzenbach noted.

“It’s not just a family and kid issue,” she said. “The college student going to class hungry, the senior living alone … they are feeling it, too.”

Cycle continues

That’s the case for many who visit the Valley Community Pantry in Hemet, a city of more than 90,000 located in the San Jacinto Valley in Riverside County.

Arlene Arlet, 65, was one of 15 people who waited in their cars at a food distribution in July. Living on a fixed income, Arlet said she struggles to afford her monthly medications with food prices spiking.

Over 21% of Hemet residents are 65 or older, and 17.8% of all residents live in poverty, according to 2020 U.S. census data.

“When gas is over five bucks a gallon and food is double in the stores, you have nothing left at the end of the month,” Arlet said. “It all feels like spit in your face.”

Parked next to Arlet was Carmen Moreno, 63, who has been on disability since 1992. She is sticking to buying items on sale, she said.

“You get $100 for groceries and really it’s nothing,” Moreno said of the monthly CalFresh benefits she receives. “It’s becoming harder and harder every visit to the market.”

A fully stocked room of food at the Valley Community Pantry in Hemet, California. Organizers say the volume of visitors to the pantry has risen sharply since 2021. (Photo by Javier Rojas/Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/ SCNG)

Jim Lineberger, Valley Community Pantry director, said the majority of those who seek services there are older people on fixed incomes. Many lack reliable transportation and live far from a grocery store, he said.

“Being able to afford groceries shouldn’t be a problem in this country but sadly, it is,” Lineberger said. “It seems like a never ending cycle.”

Another group hit hard by higher grocery prices is college students.

A quarter of UC Riverside’s students consider themselves to have “very low food security,” while 20% face “low food security,” according to a 2020 University of California undergraduate experience survey.

While UC Riverside has made strides in food access through educational campaigns and CalFresh signups, “there is a lot of work to do,” said Sesley Lewis, director of the university’s student needs program.

Food insecurity is often connected to other issues, she said. Students accessing the campus food pantry, for example, often need help in other areas, including housing and transportation.

“To meet one need and not the other means they are still struggling,” Lewis said. “Often, going to sleep hungry feels like the least of their issues.”

Paycheck to paycheck

Back at the food distribution in Bloomington, a mile-long line of cars waits at 10 a.m.

Volunteers use walkie-talkies to direct street traffic and warn people the food distribution ends at 11 a.m.

It’s a conversation that never gets easier for Ariel Ecasa, a pastor who has worked with Vida Life Ministries for six years.

He points to a chain-link fence where the line of cars typically ended in the summer of 2021. Now, he says, he would need a ride to get to the end of the zigzagging line of cars.

“At this point, it’s every month we are seeing an increase,” Ecasa adds.

A volunteer helps with intake during a food distribution at Vida Life Ministries in Bloomington, California on July 16, 2022. (Photo by Javier Rojas/Inland Valley Daily Bulletin/ SCNG)

In 2021, the church distributed an average 100 pallets of food during giveaways. That number almost doubled the first six months of 2022, according to volunteers.

“People here are just working paycheck to paycheck,” Ecasa says. “And when everything is going up, food is probably the last thing you’re going to think about.”

One significant factor in the recent demand for food assistance, according to Medina, the Vida Life Ministries’ CEO, is the lack of economic opportunities in the Inland Empire.

As an example, he points to the church’s location in Bloomington, an unincorporated community in San Bernardino County. Here, the average household income was $62,690 and 15.3% of the population lived below the poverty line in 2020, according to U.S census data.

“The good-paying jobs aren’t here. Just look around,” Medina says, nodding his head toward a nearby Amazon warehouse built in the past few years.

“People here have just enough to pay the mortgage and car loans but their refrigerators … empty,” he adds.

Economic uncertainty is one reason the Zavalas show up every weekend for food.

One bad stroke of luck leads to fears they’ll lose their home or be unable to pay their car loan, according to Jesus Zavala, the eldest son in the family. But with the help of the church’s food distribution, he and his family can worry a little less about where their meals will come from.

“Everything that we work for is used on rent, gas and groceries, leaving us with very little,” Zavala says. “Life is hard right now, it really is.”

As the line of cars rolled forward, Medina notices a familiar van, the back seat filled with sleeping children and the passenger seat occupied by a small Chihuahua.

“Good morning,” he says with a smile. “It’s been a while since we’ve seen you.”

Editor's note: This story was updated to correct the percentage of poll respondents who said they recently worried about not being able to afford groceries.