CalFresh access a challenge for some hungry households in Riverside, San Bernardino counties

This story was originally published in Daily Bulletin with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

Riverside County Department of Public Social Services employee, Adriana Magana, talks with Diana Hernandez of Riverside regarding Calfresh benefits during a community health fair at Arlanza Elementary in Riverside, Ca., July 30, 2022.

(Contributing Photographer/John Valenzuela)

The $250 on Diana Hernandez’s CalFresh food benefits card doesn’t go as far as it used to.

A single parent, the 26-year-old juggles working at a grocery store and driving for Instacart, all while taking care of her two children.

But like many others in the Inland Empire, the Riverside mom has watched the cost of everything skyrocket this past year — from an increase in her monthly rent to paying more at the gas pump. Above all, she’s noticed that her food benefits aren’t keeping pace with rising prices at the grocery store.

“I’ve been out of my food stamps for like two weeks now,” Hernandez said while visiting a community resource fair at Arlanza Elementary School in Riverside. “It used to last us through the month but now, (the cost of) everything is double.”

As of December 2021, 4.5 million people in California, nearly 12% of the population, received monthly food benefits from CalFresh.

The estimated number of people eligible for program benefits in Riverside and San Bernardino counties is 421,552 and 424,540, respectively.

To be eligible for services, households generally must earn less than 200% of the federal poverty level. In California, that means incomes must fall under $55,500 for a family of four in 2022.

But as the rise of inflation in recent months means the costs of everyday goods and services continue to jump across the region, low-income households that rely on CalFresh are navigating a period of reduced assistance.

Riverside County Department of Public Social Services employee Ilse Gonzalez works with a family applying for food assistance benefits during a community health fair at Arlanza Elementary School in Riverside, Ca., July 30, 2022. (Contributing Photographer/John Valenzuela)

‘Tough sacrifices’

While food benefits were expanded and bolstered several times throughout the pandemic, including a minimum of $95 in emergency allotments for all households receiving assistance, there’s been an obvious loss in purchasing power at the grocery store.

Between July 2019 and July 2022, the maximum CalFresh benefits a household could receive increased 7.4%, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. But the rate of inflation in Riverside and San Bernardino counties reached 9.2% in July, the second-highest rate in the nation that month.

The Consumer Price Index for groceries nationally climbed 13.5% year-over-year in August. That was the largest 12-month increase in 43 years, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In San Bernardino and Riverside counties, the cost of groceries overall increased 11.4% in the past year. The price of some essentials jumped even higher — bread, for example, costs 18.5% more than it did a year ago.

Each fiscal year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which administers SNAP, adjusts allotments. So benefits are expected to increase this month to reflect inflation between June 2021 and June 2022. A family of four can expect to receive $939 a month, up from $835, for example.

But that increase will come as the pandemic-era $95 emergency allotments — tied to expiring public health emergency declarations — are phased out.

Maintaining the status quo in SNAP benefits at a time when high inflation is cutting into disposable incomes means some households must stretch their dollars like never before, said Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, a U.S. economist and professor at Northwestern University.

“People have had to make tough sacrifices,” Schanzenbach said. “When the SNAP benefits don’t cover everything, at the end of the day you still have to put food on the table.”

Though many households will see increases in their CalFresh allotments, there are those who may not qualify for services.

This is the reality for Manuel Vargas, 27, a Riverside resident who lives alone and works. He applied for benefits in 2019 and was told he made too much to qualify as a single person.

With prices increasing at grocery stores, Vargas has resorted to food banks for the first time. He has fears now about going hungry, he said.

“It’s a terrible feeling,” Vargas said while waiting in line at a food distribution at Vida Life Ministries in Bloomington this summer. “I didn’t always have to do this but everything is expensive, especially food.”

Left out

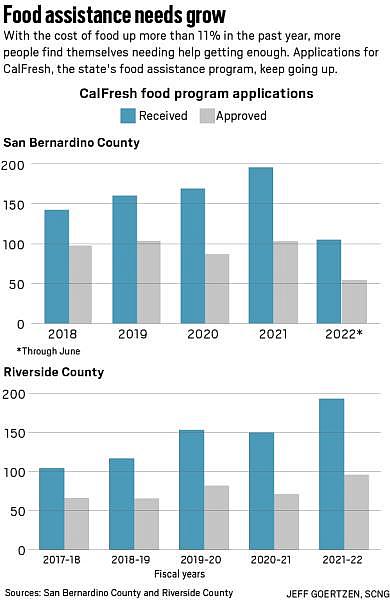

In the Inland Empire, the number of CalFresh applications received this year is on pace to or has already surpassed the previous year’s totals, according to data from both counties.

For the first six months of 2022, San Bernardino County had received 104,978 applications, making it likely the county will top the 195,716 applications it received in 2021. In Riverside County, there were 192,881 applications for the 2021-22 fiscal year that ended in June, eclipsing the previous year’s total of 149,504.

If trends hold through the year for the number of applications, it would represent a five-year high in both counties.

Higher demand for assistance comes as the federal SNAP program saw a number of expansions in California during the pandemic to reach more individuals.

In October 2021, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law extending CalFresh benefits to college students enrolled in qualifying employment and training programs.

At public schools starting in August, under the state’s Universal Meals Program, all students in grades transitional kindergarten through 12, regardless of their parents’ income, became eligible for free breakfast and lunch, making California the first to implement a statewide free meals for school children.

And in June, Newsom announced a landmark $35.2 million expansion of state-funded food assistance to undocumented adults ages 55 and over, also the first state nationally to do so.

An analysis by the nonpartisan state Legislative Analysts’ Office shows the June expansion will reach about 75,000 people by fiscal year 2025-26.

Nonetheless, advocates with the Food4All — a coalition led by Nourish California and the California Immigrant Policy Center that calls for expanded food assistance to all immigrants — say that while the June bill is a step in the right direction, many low-income, undocumented immigrants have been left behind.

This includes many who reside in the Inland Empire, said Jared Call, a policy advocate with Nourish California. In 2015, a study estimated roughly 275,000 undocumented immigrants lived in both Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

“It’s counterproductive to have only one portion of an eligible population receive help when there is an obvious need with the other,” Call said.

Citing a report by Food4All, Call said 45% of all undocumented immigrants live in food-insecure households. The largest age group affected are undocumented children, 64% of which are affected by food insecurity, he said.

“It’s progress but more can be done,” Call said of the June expansion of benefits for immigrants. “People are being left out and that’s unacceptable.”

Alex Cena, 8, of Riverside, plants carrot seeds in a small cup to take home during a community health fair at Arlanza Elementary in Riverside, Ca., July 30, 2022. (Contributing Photographer/John Valenzuela)

Overcoming barriers

While CalFresh has seen demand and its reach grow in recent years, there are still many who qualify for assistance but aren’t receiving help.

In a region where access to affordable and healthy food can be difficult, for many, accessing CalFresh presents another challenge.

Though roughly the same number of people in Riverside and San Bernardino counties are eligible to receive CalFresh benefits, the enrollment rate shows a stark contrast.

In 2020, about 86% of households eligible to access food benefits in San Bernardino County were enrolled, but in Riverside County, that number dropped to about 68.5%, according to the state’s CalFresh data dashboard.

The lower participation rate in Riverside County can be attributed to several factors, according to Adriana Magana, a eligibility food benefits technician with the county.

While the county’s Department of Public Social Services, which runs the CalFresh program, has made efforts to reach more people through educational outreach and partnerships with local schools, Magana said there are issues with staffing vacancies and casework backlogs, and often there are problems connecting with individuals when there are questions on an application.

Meanwhile, there are some who may avoid applying altogether due to a stigma Magana often hears about with food assistance programs.

Once federally known as the Food Stamp Program, the name was changed to SNAP in an effort to end an often negative association that follows those who receive government aid. But Magana said many hold fast to long-held views against taking so-called handouts, including many seniors.

There are also longstanding concerns from the undocumented community about using a public benefits program, Magana said. Some fear applying for CalFresh will be counted against them when applying for a green card or citizenship.

As of March 2021, CalFresh is not considered a public charge program, meaning using benefits won’t affect one’s legal status. All children born in the U.S. can get CalFresh benefits if they qualify — it does not matter where their parents were born.

“We are trying to properly educate people all the time,” Magana said while helping individuals at the community resource fair at Arlanza Elementary.

“But there is still this reluctance sometimes to accept that help,” she said.

Then there are those who don’t qualify but still need help, like Vicente Guerrero. The 40-year-old Ontario resident applied for CalFresh benefits this year but was denied.

Although he spends 80% of his income on rent and utilities, he said, he was told he made more than the maximum allowed for his three-person household that includes his wife and son.

With cost-of-living increases, including a rent hike this year from $1,700 to $2,800 a month, Guerrero is now working two jobs.

The struggle to provide food for his family persists, he said. His wife requires a special diet due an autoimmune disease, meaning cutting back on certain pricier grocery items is nearly impossible.

Trying to keep within his family’s means, Guerrero has turned to a local church’s food pantry, where an hour-long wait greets him on weekends. If the lines get too long, he turns around and goes home.

When asked if he’d consider applying to CalFresh again, Guerrero said he’d rather not deal with another rejection.

“It really angers my wife and I when we see that we are scraping every dollar to get something for the next two to three days,” Guerrero said. “It’s frustrating.”