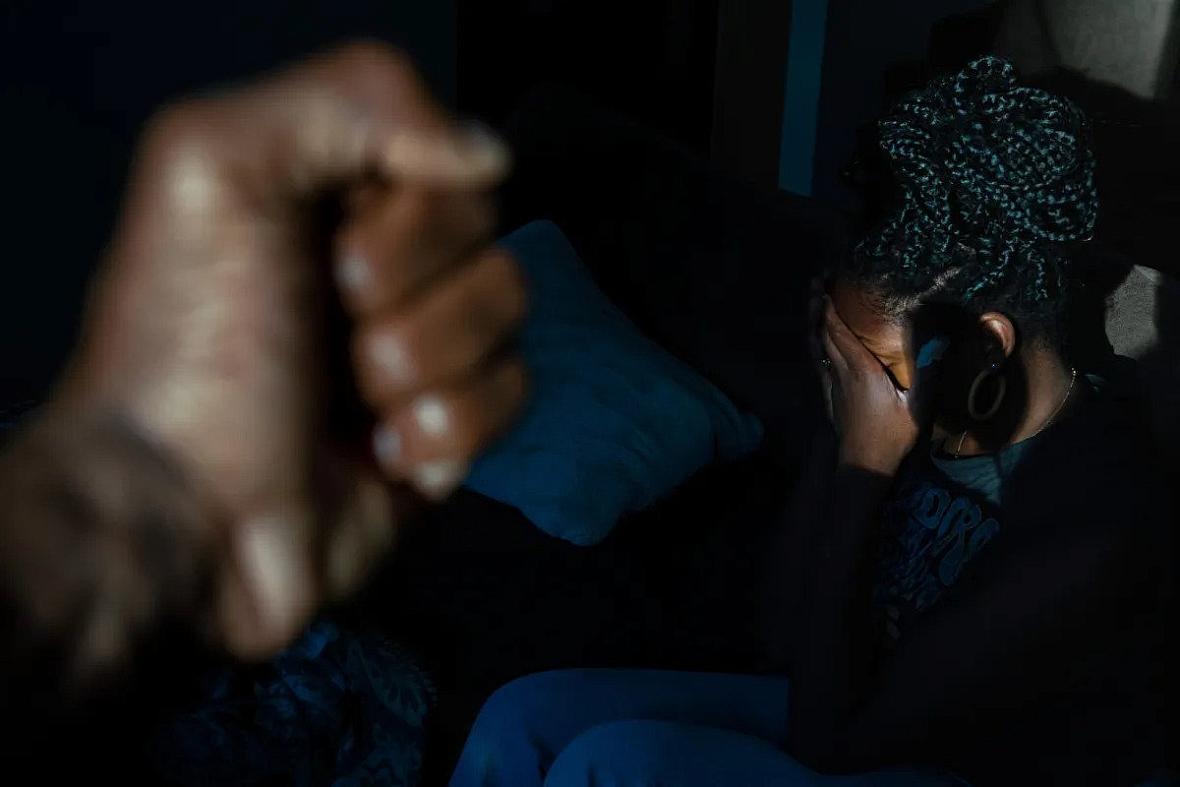

Advocates Call For Change In Intimate Partner Violence Response

This project was originally published in The Observer with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism‘s Domestic Violence Impact Reporting Fund.

Louis Bryant III, OBSERVER

The Observer

As domestic violence and intimate partner violence spike and trust in law enforcement seems to wane, advocates say they’ll continue to stand in the gaps and shake up a system that isn’t serving survivors.

The Justice Teams Network, a statewide project of the Sacramento and Oakland-based Anti-Police Terror Project (APTP), recently released its “Interrupting Intimate Partner Violence: A Guide for Community Responses Without Police.” The guide, leaders say, seeks to outline “other pathways” to responding to intimate partner violence (IPV).

“We’ve released a series of guides over the last 14 years of our existence, but this is the first guide on IPV. It’s actually phase two of a multiphase strategy of responding to community crises without law enforcement,” shared Cat Brooks, APTP co-founder and Justice Teams Network executive director. “Phase one was our guide and our model for responding to a mental health crisis. We are the only non-911 response to mental health crises in both Oakland and Sacramento. The third phase will be substance abuse.”

The goal of the new manual, she said, is to provide survivors, organizers and others with practical and safe considerations and tools to create a community-first response.

“A community-first model will be most effective if it is highly localized – at the neighborhood level, or even block by block. It could be situated within your church, mosque, synagogue, place of worship, community clinic, or resident safehouse. It must be owned and operated inside that community,” reads the manual.

Advocates argue that domestic violence and IPV responses need to be more vigorous than mandatory arrests that often place victims in danger of further abuse or being arrested themselves and also largely fail to address the rehabilitation needs of the aggressor.

“It doesn’t mean that somebody doesn’t have to go, it just means that they don’t necessarily have to go to a jail or prison,” Brooks said of a different approach. “That’s just going to be more violent. What we’re calling for is an investment in funding for transformative justice programs that are very much about accountability and transformation and healing, addressing the trauma inside of the person. That’s the cause of harm that has taught them to express their trauma through violence.”

It’s also “about safehouses for women who really do need to get all the way away,” Brooks added. “It’s about healing the entire family unit, but the reality is that the vast majority of people [involved in IPV cases], in the 90th percentile, are coming home from jails and prisons, period. They’re coming home without resources, support, healing or any real extra accountability. And we have the gall to be upset when they offend again.”

There’s accountability in addressing the whole family: “Sometimes that does mean separation or you have to go away for a little bit. How do we reimagine the places where these people go to?”

Support Grows For New Approaches

Brooks introduced the new guide recently during the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence’s statewide conference. The theme of the gathering was “Shifting the Lens 2022: Survivors and Families Coming Into Focus.” The guide includes remarks from Colsaria Henderson, the partnership’s board president. “I often thought about how people that call the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence 24-hour hotline could have called 9-1-1 if that’s what they wanted, but they called the hotline instead,” Henderson said.

“They dialed additional numbers to reach us instead of dialing 9-1-1, and I want to have another option to help someone. If they wanted law enforcement involvement, they would have called law enforcement in that moment. What advocates want is to be able to have something, a resource, an ability to say; ‘OK, there’s another way to help you find safety, security, whatever the goal is for them.’”

As the guide points out, most survivors don’t report IPV to law enforcement. Those who do often share negative experiences. A survey released by the National Domestic Violence Hotline in October found that of survivors who had called law enforcement in IPV situations, 39% felt less safe after calling and 40% stated that it made no difference in their safety. Eighty percent of survivors said the police either did not help or made things worse. Ninety-two percent of those who didn’t call the police said they feared how they’d react.

“What this survey lays out with painful clarity is that the main reason domestic abuse victims reach out to law enforcement is because there is no other alternative,” said Katie Ray-Jones, CEO of the National Domestic Violence Hotline. “It is a powerful reminder that we need to look beyond the criminal legal system for responses to violence that actually meet survivors’ needs for justice and safety, including social services, mental health supports, community interventions, housing resources, financial assistance and more.”

Support for the efforts to remove law enforcement from such situations has spread exponentially, Brooks said, in the wake of calls to defund law enforcement and despite a concerted misinformation campaign to discredit them.

“Defund was about investing community resources into community responses to crises that don’t need a badge or a gun,” she said. “Despite the all out assault by the state on these efforts, you’re seeing these programs spring up from not only grassroots organizations, but also municipalities across the country.

“I think that we have reached a place where there’s a general acceptance of the fact that police are bad at responding to certain types of community crises. We’re seeing investments all over the place, in folks, by folks in these types of models, both physically, emotionally, psychologically. It’s a real game changer as we talk about what keeps us safe and what doesn’t.”

Successful Models Found Nationwide

APTP and its Mental Health First mobile units are leading by example. There are others who are also changing the game. “I’m normally talking [negatively] about my city government, but I’ve got to say that what Oakland has done with MACRO, is phenomenal,” Brooks shared.

She’s referring to the Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland, a community response program for nonviolent, nonemergency 9-1-1 calls. The program seeks to “meet the needs of the community with a compassionate care first response model grounded in empathy, service, and community.”

“The reason why it’s phenomenal is because they’ve maintained their commitment to community. They’re always in conversation with us,” Brooks said. “They didn’t do what cities normally do, which is to weigh something that the community creates down with red tape and bureaucratic trash.”

She also points to Denver’s Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) Program that deploys emergency response teams to low-risk calls involving individuals experiencing distress related to mental health issues, poverty, homelessness, and substance abuse. STAR is dispatched through Denver 9-1-1 Communications. Dream Defenders in Florida and the national organization Interrupting Criminalization, founded by Chicago organizers Mariame Kaba and Andrea J. Ritchie, also is doing standout work, Brooks said.

“Interrupting Intimate Partner Violence: A Guide for Community Responses Without Police” is a product of years of work and credits those who laid the framework.” Brooks explained. “I want to be really clear: we’re building on the tradition of our ancestors. Black and Brown and indigenous folks have been responding to crises in our communities without the help of the state forever because we didn’t have the luxury of relying on the state for anything but violence.

“But the reemergence of this, the formalization of this and the normalization of it for our folks, a lot of that happened as a result of the launch of MH First and it’s exciting about the doors that it’s opened. It’s a harder conversation when you’re talking about domestic violence even with abolitionists, but there, too, we see the field shifting from just the carceral response to one that actually meets the demands of survivors – which, by and large, is not to utilize law enforcement.”