Amputees Lost in the COVID-19 Shuffle

This is the second in a two-part investigation addressing racial disparities related to amputations during COVID-19. The first addressed how the pandemic impacted preventive care aimed at preventing amputations. This series was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 California Fellowship.

WEBMD HEALTH NEWS

When the toes on his left foot turned black, Anthony Sambo knew what it meant.

Three weeks earlier, in December 2020, the Filipino nurse caught what he assumed was a cold; the busy Chicago dialysis center where he worked had stayed open throughout the COVID-19 pandemic since it is an essential service for patients with kidney failure. Two days after Sambo started coughing, he was diagnosed with COVID-19. Four of nine co-workers got it, too.

Sambo, with fellow nurse Marie Costan, before his amputation.

So began the journey that would lead Sambo to spend most of that winter in the hospital. During that time, the novel coronavirus not only plagued his lungs, but also wreaked havoc in his blood: The virus is known to cause clots that block blood flow through arteries, including those in the legs and feet, which can lead to amputations. By the time he was wheeled out of the facility in February 2021, he’d lost 3 months of his life, 20 pounds in weight, 5 toes, half his foot, and his ability to walk.

Back at home, surrounded by guitars and rosaries, Sambo felt “lucky … for having lived through it,” he says, “and that, at the end of the day, I only lost a foot.”

However, the Desert Storm veteran’s battle for survival as a new amputee was only just beginning. Almost a year later -- due to a combination of pandemic delays, insurance snafus, and miscommunications -- he’s still living without a prosthetic limb, all but immobile.

For the 500 Americans who get amputations every day, the procedure is not the end. Living without a limb is more physically demanding and places a lot of strain on the heart. That stress is one of the many reasons that nearly three-quarters of amputation patients may die within 5 years. Physical therapy to condition the heart and prosthetic care to reduce energy use are critical for amputees to survive and thrive.

But getting this kind of care is no small errand.

Physical therapy can vary in quality and quantity. Rehabilitation facilities may not be available locally, and at-home rehabilitation may not be feasible. And any or all treatments may not be covered by insurance. Navigating the world of prosthetics is an obstacle course by itself.

During the pandemic, the obstacles were even higher as beds at rehabilitation facilities were filled by patients with COVID-19 and the offices of doctors, therapists, and prosthetists closed.

“The treatment of amputees is in the dark ages, and COVID only made the dark ages darker,” says Demetrios Macris, MD, a vascular surgeon in San Antonio, TX.

Referring to the delays in care, “every week lost adds up,” he says. “Sitting down for the rest of your life -- that’s a recipe for disaster.”

Lost in the System

More than 250 miles east of San Antonio, Red Nash sat for nearly a year and a half.

Her saga began in the summer of 2018, with a cramp that wouldn’t go away. The Galveston, TX, native saw doctor after doctor, who sent her home with pain pills and pep talks.

Nash went from walking on three legs (with a cane) to four legs (crutches) to not walking at all (a wheelchair). She quit her job as a manager at a leather wholesaler, unable to take inventory, hoist products, or walk across the 2,000-square-foot store. In May 2019, her foot turned black, and a month later, Nash lost her leg. Her initial cramp was a symptom of peripheral artery disease, which causes the vessels that carry blood from the heart to the legs to narrow or get blocked.

The surgical wound grew infected, and Nash spent the next 4 months in and out of consciousness. In November 2019, Texas Medicaid denied her a prosthesis; she appealed, and in March 2020 the program denied her again. (Texas Medicaid does not cover prosthetic limbs for adults.)

In August 2020, after “throwing a dart at a map,” she moved to North Carolina. A month later, she was approved for the prosthesis, and in November 2020, she started physical therapy.

On a pandemic-era New Year’s Eve, she received her new right leg, standing on two feet for the first time in 17 months.

Once amputees have recovered from surgery, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs guidelines recommend that patients like Nash be discharged to a specialized rehabilitation facility.

These facilities are critical for helping amputees like Nash and Sambo get back on their feet, says Alberto Esquenazi, MD, a rehabilitation medicine doctor at Temple University. They can quarterback the coordination of care across the mass of providers, he says, rather than “putting it all on the amputee.”

Indeed, studies have found that those discharged to a rehabilitation facility are more likely to receive a prosthesis, use their prosthetic limb more often, and walk sooner; and they are less likely to require another amputation, compared to those discharged home or to a skilled nursing facility. Historical data shows that getting good rehab care early also increases the likelihood of surviving more than a year.

“Coordinated care saves money, time, effort, certainly the aggravation of the patient, and possibly lives,” Esquenazi says.

But during the COVID-19 pandemic, too often these facilities closed their doors to amputees.

Across the country, many were transformed into “overflow” units amid viral surges. That meant in places like Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in the Bronx, NY, -- which is right next to New Rochelle, one of the nation’s earliest hot spots -- therapy gyms became makeshift wards lined with gurneys and oxygen tanks.

Meanwhile, rehabilitation facilities that stayed open were all but out of reach for amputees for months, Esquenazi says.

According to Medicare claims data analyzed by ATI Advisory, a health care research firm, between March and December 2020, thousands of COVID-19 patients were discharged to rehabilitation facilities, as nursing facilities were overwhelmed. In part, the shift was prompted by emergency measures enacted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

“Facilities were just not taking [amputees],” Esquenazi says. “So those patients went home -- and, at home, they tended to sit there, waiting.”

Missing the ‘Window of Opportunity’ for Rehabilitation

For those discharged home like Nash, early, intensive, and regular physical therapy is key to recovery.

Lots of things can go wrong soon after surgery to prevent amputees from walking again, says Kelly Kempe, MD, a vascular surgeon at University of Oklahoma.

As muscles go unused, they can shorten and tense up, freezing up the residual limb. Painful pressure ulcers can develop, sentencing amputees to bedrest until the sores heal. Blood clots, pneumonia, and urinary infections can turn a difficult recovery deadly, Kempe says.

“In order to maintain a quality of life with independence, as well as to reduce the patient’s risk of early death, rehabilitation is an absolute must,” she says, “it is a matter of life and death.”

The life-saving potential of physical therapy for amputees is especially important in light of what experts refer to as the “critical window.” Starting rehabilitation soon after hospital discharge has been shown to improve patients’ independence at home. And short-term delays in rehabilitation have also been linked to a lower likelihood of walking in the long term.

“By waiting, you’ve missed that window of opportunity, and you can’t get it back,” Esquenazi says.

Yet, research from Veterans Affairs hospitals shows that only 65% of vets with lower-extremity amputation receive outpatient rehabilitation within a year, even though the VA has guidelines recommending physical therapy, protocols to guide its use, and covers the cost of services.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, “many people who might have gone to rehab in normal times went home,” says Olamide Alabi, MD, a vascular surgeon at Emory University in Atlanta. It’s also unclear whether these people received the appropriate resources because “home health PT is hit or miss,” she says.

And that’s assuming you can get it. Surveys done by the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) show that, as of May 2021, 30% of therapists had been laid off, furloughed, or resigned in the past year. A quarter of outpatient practitioners had cut their hours. Almost half of outpatient clinics had closed at some point.

The ‘Foreign Universe’ of Prostheses

In addition to functioning muscles, amputees also need prosthetic limbs to help stay upright. Walking independently on prostheses can improve the health and well-being of amputees a great deal, Alabi says.

A study from the 1990s, following 400 amputees over 5 years after completing a rehabilitation program, found that those who stopped using their prosthetic limbs were less likely to be able to perform basic tasks such as walking alone, climbing stairs, or getting up from the floor after a fall than regular users. Another study, of more than 4,500 veteran amputees, found that those who did not get a prescription for a prosthetic limb were more likely to die within 3 years of their surgery than those who got a prescription.

Getting a prosthetic limb, as Red Nash knows, takes no small amount of work, especially for those who aren’t part of the VA or covered by Medicare. (Sambo, who is a veteran, receives most of his care outside the VA and has not yet pursued prosthetic care through the system.)

To receive Medicaid, patients must first qualify for disability -- a process that takes months. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, many states, such as Texas, not only restrict which Medicaid patients can get prostheses, but also dictate when, which type, and how many they can get.

Those with private insurance face hurdles too. While prosthetic limbs are an “essential health benefit” in nearly all states -- meaning that they must be covered by insurers -- according to the Amputee Coalition, restrictions, caps, and exclusions remain common.

Such frustrations -- wait times, transferred calls, lost faxes -- can shackle amputees to their beds, wheelchairs, and walkers indefinitely.

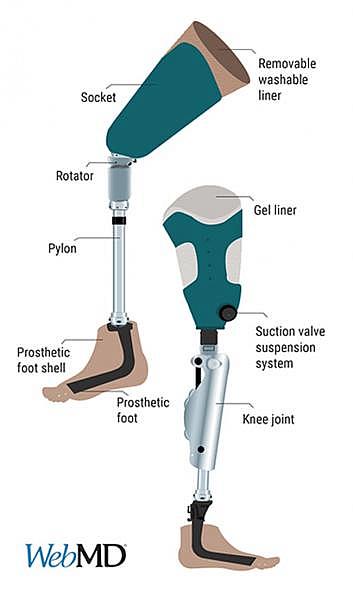

Examples of prosthetic lower-limbs.

Getting lost in the system is all too common for new amputees, says Kempe. They rely on numerous providers for care -- doctors, wound specialists, podiatrists, physiatrists, prosthetists, physical therapists -- and coordinating all the services they need across disciplines and departments can be a tall task for those stuck, horizontal, in bed.

In San Antonio, Macris’s patients are similarly challenged: Navigating these institutions is like crossing into “a foreign universe” for new amputees, he says.

And after navigating complicated insurance policies, there remains the tough process of finding a prosthetist.

That relationship is critical: “They will get to know you in a way not many others will,” says amputee Mary White, since prosthetic limbs require frequent modifications, repairs, and replacement -- especially in the early months after surgery.

After a motorcycle accident on Memorial Day weekend of 2019, White lost her left leg below the knee. The “lower 10 centimeters of [her] leg were turned into dust and powder” from the collision, White says, and she needed a skin graft and 6 months to heal. (The wound looked like “the bride of Frankenstein,” she says.) In November 2019, she met with her first prosthetist.

But when the wraps he prescribed caused redness and pain, she got a second opinion. In March 2020, she received her first prosthetic limb, but a couple of weeks later, the surgical wound resurfaced. After many attempts to refit the prosthesis, she switched again. In August, a new prosthetic limb; in September, a new wound. By October 2020, the prosthesis didn’t fit. To date, White’s run through half a dozen prosthetists and 20 temporary legs

Such struggles aren’t unusual, says Yitzhak Langer, a Maryland-based prosthetist with Presque Isle Medical. By making in-person care harder for people like White to receive, the pandemic likely only made the challenges worse, he says.

Getting the socket to suit the limb and getting the sole properly aligned with a patient’s gait is complicated, he says. As patients’ wounds heal, swelling eases, weight fluctuates, and scar tissue forms. In his tomato-red truck, Langer drives hundreds of miles per week up and down the Atlantic coastline to drill, wrench, saw, grind, bevel, and glue legs to a perfect fit.

Langer adjusting a prosthetic leg.

Ensuring a perfect fit isn’t merely cosmetic, Langer says. It’s essential to keep traumatic residual limb and phantom limb pain at bay -- pain that plagues most amputees -- and can drive them to abandon their prosthesis altogether. Limb pain can also lead to depression, which is already prevalent among amputees.

That “building up of hopelessness is very dangerous,” says Langer, since it can become a vicious cycle of further immobility caused by amputees thinking, “‘OK, maybe I’m never going to walk again.’”

A bad fit may lead to skin breakdown, wounds, and new infections, Langer says. And poorly fitting prostheses can increase the risk of potentially debilitating falls.

Despite the benefits of prostheses, some studies show that barely half of amputees get them after surgery. During COVID-19, the canyon between amputees and prosthetic care was even wider, Langer says, especially early on.

For months, he couldn’t get into nursing homes or rehabilitation facilities. Disability qualifications were delayed. And even for patients he was in touch with, visits were sporadic: Ever-changing COVID caseloads led to rain checks and cancellations.

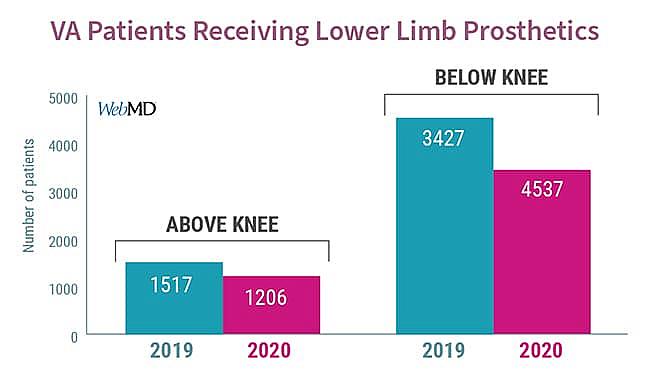

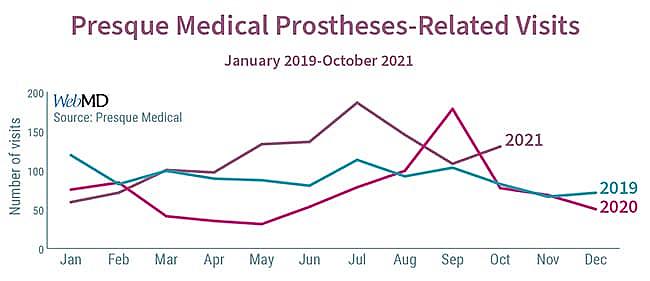

All told, at Presque Isle Medical (which sees hundreds of patients a month), visit volume fell nearly 50% from March through July 2020, compared to the previous year. According to VA data, the number of patients receiving new above- or below-the-knee prosthetics decreased 20% and 25%, respectively, between 2019 and 2020.

So, for months, patients like Mary White and Anthony Sambo were all but on their own.

Beginning in August 2020, the visits picked up again, skyrocketing in September, according to Shlomo Heifetz, Presque Isle Medical’s director of operations. As of October 2021, the number of annual visits remained 20% higher than the 2019 baseline. “It was like a waterfall, the dam broke loose,” says Heifetz. “There was a tremendous influx of patients who had just been sitting there, awaiting care.

“It wasn’t that the patients weren’t there,” he says, “it was that they couldn’t be treated.”

For Mary White, the fits and starts to her post-amputation care took their toll. In April 2021, after receiving another prosthesis, she stuck her toes in the sand for the first time in years along the shores of New Hampshire. “Please don’t give up,” she wrote to other amputees in a Facebook support group at the time, “keep at it!”

But after another abscess formed, White is back in a wheelchair. She thinks that more consistent communication with prosthetists might have changed how her saga played out.

“It’s really hard when you’ve clawed your way to the top, doing everything you were doing before,” she says, “and then you’re shoved off, only to find yourself at the bottom again.”

Structural Racism in Prosthetic Care

Along with the challenges of post-amputation care are the injustices that put underserved communities at even higher risk, Alabi says.

A study of nearly 10,000 veterans found that African-American patients are less likely to be prescribed prostheses than white patients.

“Do you think it’s something about the Black amputation stump that makes it unable to fit in a prosthetic?” says Alabi, “No: There’s something else going on there, likely related to structural racism.”

Sean Harrison, a patient advocate for the Hanger Clinic -- the country’s largest prosthetic provider -- witnesses it every day.

Harrison with his dog.

Harrison, who is a Black amputee, travels hundreds of miles each week through the California sunshine to assess patients’ recovery status and needs. And too often, Harrison says, the odds are tilted against amputees of color.

“When you have someone who doesn’t trust a system that has failed them so many times -- and then you ask them to engage, to come back, over and over -- that’s not a recipe for success,” he says.

Another consideration unduly afflicting amputees of color is poverty. When it comes to recovery, “income equals outcome,” he says: sterile bandages, cleaning supplies, and safety equipment all cost money these individuals can’t spare. For people in poverty, Harrison says, “it’s like the system is set up to fail.”

The same is true in Texas: Three-quarters of the applications to the Prosthetic Foundation -- a nonprofit that funds prosthetic services for amputees in need -- are middle-aged Hispanic men, according to the organization’s executive director.

Another source of structural racism may be the “K-level” system of classifying amputees (otherwise known as the “Medicare Functional Classification Level”).

K-levels were originally developed to predict the functional level for a given amputee, says Robert Gailey, PhD, a prosthetist and professor at the University of Miami who sat on the original Medicare committee that started the measure. The prosthetist assigns each patient a K value by taking into consideration their history, “desire to ambulate,” and current condition.

But there is no standard way to assess these potential functional abilities.

“It’s really up to clinicians to define how they want to determine it,” says Matthew Major, PhD, a prosthetist and associate professor at Northwestern University, leaving the evaluations vulnerable to subjectivity.

More objective measures, such as whether the person can get out of a chair or how long it takes them to walk a specific distance, are reliable, but surveys suggest that many prosthetists do not use them routinely when assigning K-levels. Perhaps as a result, the reliability of the K-level has come into question. A survey of over 200 prosthetists that Major co-authored found that two-thirds of respondents didn’t believe that K-levels accurately assign rehabilitation potential.

As such, when insurers use K-levels to ration very expensive prosthetic equipment, things get especially problematic, Gailey says. (Most insurers, not just Medicare, use the scoring system.)

For example, below-the-knee amputees must score a “K3” to be eligible for a high-tech prosthetic -- a device that can cost tens of thousands of dollars. But in one small study, amputees who would not have qualified for the more costly prosthetic based on their assigned K score fell less with this equipment and improved their walking abilities so much that they “graduated” to a better K score. Similar improvements were seen with K2 foot amputees who were allowed to train on K3 prosthetic feet.

Prescribing lower-functioning equipment based on assigned K score becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, Major says, because “when you assign someone a K2, and you give them K2 technology, they will behave like a K2.”

Gailey agrees: A small study he led with 16 veteran amputees found that after 8 weeks of rehabilitation, most graduated an entire K-level above their baseline rating.

“There are a lot of people, especially those in impoverished areas of the country, who would benefit if given a better chance with the appropriate prosthetic devices,” he says.

“There is always the potential … to become a victim of implicit bias,” Gailey says, “which could have a huge negative impact on patients and their rehabilitation.”

A 2017 Consensus Statement by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Lower Limb Prosthetic Workgroup called for more research into the question, but so far, the options for K2-scoring amputees remain limited.

“Amputation research in general has been focused on white men,” says Sheila Clemens, PhD, an assistant professor and physical therapist at Florida International University.

There hasn’t been much research evaluating disparities in post-amputation outcomes since the VA serves as a major funding source. But a small study that she ran during the pandemic (shared with WebMD, but not yet published) supports Gailey’s and Harrison’s observations: Amputees of color took significantly longer to get up from a seated position, and they could not walk as far in 2 minutes as white amputees.

With these data in hand, Clemens says, “we now know that what we thought is happening, is happening.”

A One-Woman Amputee Hotline

In some corners of the country, providers are working hard to try to prevent these seemingly inevitable disparities.

After attending undergraduate and medical school in New Orleans, vascular surgeon Leigh Ann O’Banion, MD, decided to return home to “give back to a community that’s given so much to me.”

Growing up in California’s fertile Central Valley, she would peer out the window of the car on her way to school to see the workers toiling in the fields amid the blazing summer heat -- picking, trimming, and packing the produce that might soon find its way on an 18-wheeler due east. By feeding the country one bushel at a time, she realized that these workers “are the ones keeping all of us alive.”

O’Banion knew there was a need to help amputees after surgery because when she spoke with colleagues around the country, often “there was nothing in place” she says.

“Patients were getting their legs cut off, discharged from the hospital, and told, ‘Let’s just see how things go,’” she says

These disparities are why O’Banion spearheaded the creation of a comprehensive program for new amputees to ensure they receive intensive rehabilitation, outpatient physical therapy, and regular prosthetic care after surgery.

“Having random pieces in place … and expecting them to all magically come together, that just doesn’t work,” she says, “that’s where the ball’s dropped.”

In the effort to prevent disability, physical weakness, and fatality, one of the most important benefits of O’Banion’s program is simply giving amputees a number to call.

Dodson, the one-woman hotline.

Jessica Dodson, the program’s nurse coordinator, is almost always the voice at the other end. The self-proclaimed “one-woman hotline” makes sure patients have transportation to their appointments, that things are squared away with insurance, that the physical therapist actually came, and that the prosthetic is fitting properly.

“Give me a call, I am here,” she tells patients.

But still, Dodson worries about all the patients who don’t call, or don’t answer.

“There are so many complications [that patients] can run into,” she says. “Not having someone to call can kill patients.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, O’Banion fears for all those who didn’t call and didn’t answer. Rehabilitation, physical therapy, and prosthetic care “came to a screeching halt,” she says.

Family support vanished because of concerns about the spread of the virus. Financial burdens, amid furloughs and layoffs, loomed. As a result, “too often, [patients] just gave up,” she says. “I think the patients were essentially just getting lost and forgotten about.”

Harrison, the patient advocate in California, agrees: “I spent 16 months just trying to find my patients,” he says. “When you’re hopping on one leg across the river, there are so many opportunities to fall off the lily pads in normal times,” he says. With the added hurdles during COVID-19, “it was death by one thousand cuts,” he says.

And for Alabi, in Atlanta, despite “a very concerted effort to ensure people weren’t lost in the shuffle” over the past year, her patients lacked many of the services that could have aided their recovery. As internists’ offices closed, she found herself renewing routine medications, ordering screening tests, and making care-coordinating phone calls that otherwise might have been overlooked.

Alabi worries about the pandemic’s long-term impact on the recovery of patients of color.

“These are communities that were already disenfranchised,” she says. “[The pandemic] only exacerbated the disparities that were already present.”

Sitting, Waiting

For patients like Anthony Sambo, that means more sitting, and more waiting.

Nearly a year after surgery, he’s still waiting for a prosthetic limb. For now, he’s keeping himself busy strumming Lewis Capaldi on the guitar, singing Ed Sheeran on karaoke, and playing World of Warcraft on the computer.

But the days are blurring together, he says: “I keep doing the same thing over and over and over again.”

There are so many things Sambo wants to do: go to the gym, mow the lawn, plant eggplant and okra in his brother’s garden, sauté bitter melon and black beans together just like their mom used to. Not to mention getting back to work, since money is tight.

“I’m looking forward to walking again,” he says, “very, very soon.”

But, at least for now, he’s still sitting, waiting.

This is the second in a two-part investigation addressing racial disparities related to amputations during COVID-19. The first addressed how the pandemic impacted preventive care aimed at preventing amputations. This work was funded by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 California Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by WebMD.]