Behind from the start: What can be done to help women receive prenatal care — Part 3

This article is the first in a series of three articles on prenatal care in Bexar County, Texas, which were produced as a project for the National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School of Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Behind from the start: Prenatal care crisis puts babies in Bexar County, Tex., at risk — Part 1

Behind from the start: Why some women aren't receiving early prenatal care — Part 2

Expectant parents Richard DeLeon Jr. and his girlfriend, Faith Garcia, play a game during a Stork's Nest class in Converse on Dec. 15. The class focused on newborn care. Stork’s Nest volunteers educate expectant parents in an effort to prevent premature births and infant deaths.

The subject was constipation during pregnancy, but Karen Plunkett was doing her best to make things fun.

"Drink plenty of water. Put lemon in it, put lime in it, put anything but wine in it," she said, earning a laugh from the group of six expectant mothers and one supportive father.

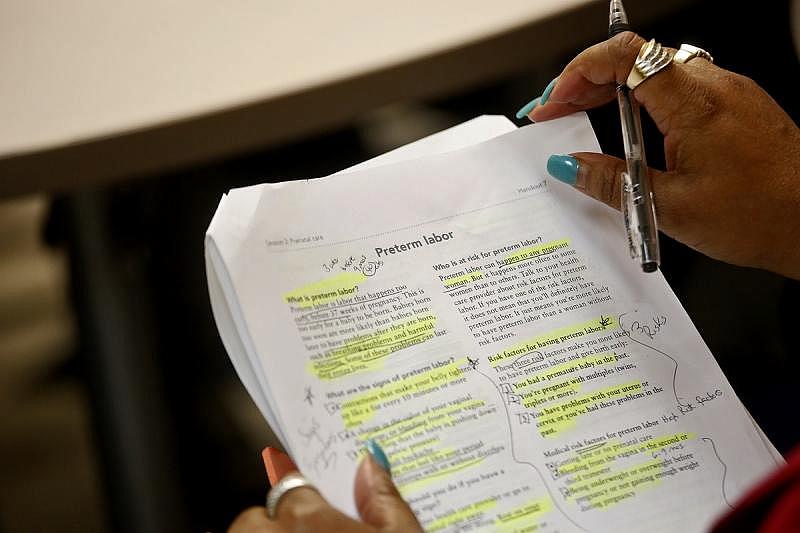

Plunkett, a volunteer, was leading a prenatal education class at a Baptist Health System clinic in Converse as part of Stork's Nest, which aims to encourage women to seek prenatal care in their first trimester of pregnancy.

The Stork’s Nest is one of a number of programs that involves community organizations, health officials and providers to try to make babies healthier. Many of them serve only a few dozen or a few hundred women at a time.

But in Bexar County, the problem is much larger. About 10,000 women gave birth in 2014 with no prenatal care or late care, defined as coming in the second or third trimester. That was nearly four out of every 10 babies born that year alone.

The number has been rising: The percentage of births to women receiving no prenatal care jumped to 15.4 percent in 2014 from 2.7 percent just three years prior.

Delaying care or not getting any at all puts the baby and the mother at greater risk of serious medical problems, such as prematurity. Bexar County has one of the highest rates in the nation of premature births, which can cause lifelong health problems for babies who survive.

Existing programs help connect mothers to prenatal care, but some experts believe more needs to be done — and on a wider scale. Women give a variety of reasons for not seeing a doctor early in pregnancy, so there's no one solution to the problem. But many report difficulty with accessing and paying for care and are uninsured.

Metro Health officials and other experts were unaware of the steep rise in the number of women with no or late prenatal care before inquiries by the Express-News for this series, and none could explain the increase.

"It really needs to be researched and discovered who these women are who are not receiving adequate care and effective outreach designed to get them in," said Dr. Thomas Schlenker, who headed Metro Health for four years until his departure in August. He, too, said he was surprised by the increasing number of pregnant women without care.

“The problem is so large, it really needs to be addressed from a population basis,” he continued, “and the first step would be to try to understand who those folks are and try to understand why they’re not getting care.”

On Friday, in response to inquiries from the Express-News, Metro Health Assistant Director Anil Mangla said he would convene a work group to do just that.

Getting the word out

Not knowing where to find help is a major reason women don't seek medical care during pregnancy, said Martha Lopez, coordinator of Ventanilla de Salud, a program funded by the Mexican Consulate to help Mexican citizens navigate the complex U.S. health-care system.

"They don’t know what’s out there," said Lopez, who keeps a stack of pamphlets for community clinics and other resources on hand to distribute to people she counsels.And so it is critical that women are educated about the need for early care and the availability of resources.

Darien Evans and Yasmeen Joya browse baby items after a Stork's Nest prenatal class in Converse on Dec. 15. As an incentive for attending the sessions, participants can pick out baby clothes. Stork's Nest is a national program launched in 1972.

The programs in Bexar County that help connect women with prenatal care are difficult to scale up because of resource limitations, said Dr. Robert Ferrer, a professor in the department of family and community medicine at the UT Health Science Center at San Antonio.

To combat the “system unfriendliness” that keeps many women from applying for health coverage and trying to find a doctor, he proposed a “community-based solution where you go out to the neighborhoods and you have programs to educate women and help find women who are newly pregnant.”

Community health workers, or promatoras, can be valuable in educating people, he said.

“Maybe have storefronts that could just be available next to the H-E-B in certain high-risk neighborhoods to help give out information and connect women with resources. But just so the availability, the visibility, the barriers to entry are lower. That potentially could help.”

Expanding the umbrella

Because lack of health coverage is a major hurdle to women getting prenatal care early, some experts believe solving that would go a long way.

When state leaders chose not to expand Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act, it created a so-called Medicaid coverage gap. In Texas, 760,000 people earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but too little to qualify for ACA subsidies, leaving them with no coverage.

Because Texas has very limited Medicaid eligibility, women of childbearing age often don't qualify. In 2014, 28 percent of women ages 18 to 44 in the state were uninsured. When a low-income woman becomes pregnant, it’s much easier for her to qualify. For a single woman with a monthly income of $1,991 or less, Texas Medicaid pays for health care during pregnancy and up to two months after the birth. The income limit increases based on household size.

An uninsured woman who is a U.S. citizen or legal immigrant can receive birth control and family-planning counseling under the Texas Women's Health Program if she earns $21,600 or less a year. The income limit is higher for bigger families.

If more women had health insurance before they got pregnant, though, they would be more likely already to have a primary care physician, Ferrer said.

They also wouldn’t have to wait for Medicaid to kick in, said Dr. Lisa Hollier, an OB/GYN with Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston. In a 2011 report by the state health department, pregnant women in Texas cited waiting for their Medicaid eligibility as the main reason for delaying prenatal visits.

Expanded health coverage would allow more women to get free or low-cost contraceptives and family-planning counseling so they could prevent unwanted pregnancies, said Marisa Spalding, a policy analyst in Washington, D.C. with the National Health Law Program, a nonprofit that advocates for low-income people. Women with unplanned pregnancies tend to get prenatal care later than women who plan them.

Having access to health care also means women are healthier when they became pregnant and so are their babies, said Spalding, whose work focuses on health disparities and reproductive health.

"Health care coverage over a woman’s lifespan is essential," Spalding said. “Any steps that we take toward expanding coverage improves the health of women and babies generally.”

Making the Medicaid application process easier and faster would help, too, Hollier said.

“I would like a streamlined application with a rapid turnaround on eligibility for pregnancy Medicaid and for CHIP,” she said. “I would love to see that rate be consistently under two weeks. That’s not happening now.”

Advocates for women’s health are calling for a change in federal policy so that pregnant women can enroll in coverage through the ACA at any time. Uninsured women who find out that they’re pregnant outside of the annual three-month open-enrollment period aren’t able to sign up for coverage through the federal marketplace. Only New York State requires insurers to allow women to change their insurance coverage when they become pregnant, regardless of the time of year.

Allowing women to sign up for coverage any time as in New York would help them to get better prenatal care with fewer out-of pocket costs, said Kate Connors, spokeswoman for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

An uninsured woman would pay an average of $2,000 in out-of-pocket costs for an uncomplicated pregnancy, said Mike Koroscik, CEO of the Institute for Women’s Health in San Antonio, an OB/GYN practice with eight locations in San Antonio. Investing in prenatal care potentially saves money later by preventing premature births, which require costly treatment.

Targeting at-risk women

Using a hand puppet and a soft fake breast, lactation consultant Karen Bohr demonstrated to four pregnant women how to get a baby to latch onto a nipple."

Get in the corner of the couch, get that Netflix going and feed all day," Bohr said.

The women recently were in a fourth-floor room at University Health System's Robert B. Green Campus downtown, learning about feeding their baby as part of CenteringPregnancy, a group approach to prenatal education funded here by March of Dimes. Before each session, the women undergo a physical exam.

“I’m learning a lot,” said 23-year-old Anna, a mother of two who has had prenatal care before.

Research has shown that the national program increases the expectant mothers’ number of prenatal visits.

Jean Lawrence lectures on newborn care during a Stork's Nest class in Converse on Dec. 15 for expectant parents including Richard DeLeon Jr. and his girlfriend, Faith Garcia, center, and Jade Brown, right, and guests.

Other programs in San Antonio share the objective of making sure pregnant women get medical care, among other goals.

Stork's Nest teaches expectant mothers and fathers about staying healthy during pregnancy, including one session about seeing a doctor early. As an incentive, participants choose items from the "boutique," a small room bursting with donated baby clothes and accessories. Each one who finishes the course receives a stroller. Stork's Nest is a project of Zeta Phi Beta Sorority and March of Dimes that launched nationally in the 1970s.

Becoming a Mom/Comenzando Bien is a free bilingual program from the March of Dimes that teaches women about having a healthy pregnancy and a healthy birth. San Antonio Healthy Start, a Metro Health program that offers information and services to pregnant women to reduce the risk of premature birth and infant mortality, offers the program in five ZIP codes with significant health disparities: 78227, 78203, 78202, 78213 and 78220. Women from outside those ZIP codes also may enroll. As with Stork's Nest, the program allows participants to earn baby-care items by attending. Honey Child is a similar March of Dimes program but faith-based and aimed at African American women.

Healthy Start also offers a home visiting program. Case managers — usually community health workers — meet regularly with expectant mothers for one-on-one instruction. They work to get moms to engage in healthy behaviors, such as quitting smoking. Healthy Start's program was expanded by a $9.7 million five-year grant from the federal Health Resources and Services Administration in 2014 to serve 1,000 participants a year. "Getting them in to see a doctor is probably the number one thing that we do," said program manager Kori Eberle.

The Nurse-Family Partnership, a national home-visiting program offered by three agencies in Bexar County, connects low-income, first-time moms with nurses from early in pregnancy until the child's second birthday. "Our first question is, 'Have you seen a doctor?’ " said Cheryl Weise, nurse supervisor of Nurse/Family Partnership at the Children’s Shelter. “If the answer is no, if they don’t even have insurance yet, that’s when the nurses kind of jump into case-worker mode and say, ‘OK, these are the community resources. What’s keeping you from getting there?’ ”

The Mommies Program, a partnership between the Center for Health Care Services and University Health System, aims to help pregnant women with substance-abuse disorders. The program provides 165 to 175 pregnant women a year outpatient addiction treatment and parenting education sessions and helps link them with prenatal care. A van gets them to doctor appointments. Babies born to women in the program spend fewer days in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Alpha Home’s Family First program works with pregnant women at risk of abusing alcohol and other drugs.

The city’s Healthy Beats program, located at Metro Health’s clinic for sexually transmitted diseases, tracks pregnant women with STDS to keep them on track with prenatal care.

Go Before You Show is a campaign in several cities across the country to encourage women to see a doctor as soon as they know or suspect they might be pregnant — even before the so-called "baby bump" appears. Healthy Start implemented the campaign in San Antonio. The website GoBeforeYouShowSA.com, available in English and Spanish, includes ways for pregnant women to find health insurance or affordable care, a list of health-care providers who will accept patients before Medicaid applications are approved and information about getting transportation to appointments.

Health-care systems such as Methodist and Baptist, Southwest General Hospital and federally-funded clinics such as CommuniCare Health Centers offer free pregnancy testing and help pregnant women sign up for Medicaid and schedule prenatal care appointments. Some offer medical care while Medicaid applications are pending and offer transportation. Some health insurers, such as Superior HealthPlan, also help pregnant women get transportation to medical appointments.

Many of the programs depend on funding from the state and federal governments, and some directors worry about sustaining them.

"Right now, home visiting itself has kind of been brought up as something (policymakers) might want to discontinue, and so I think we're all just trying to do the best we can to show that home-visiting programs work and that they need to stay active," Eberle said. “It looks like we’re OK for now,” but keeping it off the chopping block is critical.

Meeting their needs

While educating women about the importance of prenatal care is key, even women motivated to see a doctor encounter barriers, said Thankam Sunil, director of the Institute for Health Disparities Research at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Sunil, lead author of a paper published in the Maternal and Child Health Journal in 2010 about prenatal care, found that many low-income women at public-health clinics in San Antonio said they couldn't take time off from work to visit a doctor, that taking public transportation ate up hours of their day, that they couldn’t find child care or the waits to see a health-care provider were too long.

Stephanie Ulloa, left, and Paola Ramirez, with facilitator Jean Lawrence, right, pick out clothes for their babies after a Stork's Nest prenatal class in Converse on Dec. 15. Ramirez received a stroller for attending all eight classes.

Expanding the hours of clinics would make it easier for women to set appointments before or after work, Sunil said, and child-care services at the clinics also would ease the burden on harried mothers. And providing bus passes would help.

"It is very hard to bring these women into one of these facilities for seeking care, but once they come in, we need to make sure we are providing the resources and the support they need both financially and socially to meet their needs," Sunil said.

Expanding medical services in areas of town where there is a gap also could help. On the North and Northeast sides of San Antonio, access to health-care providers who accept Medicaid is limited, said Kelly Bellinger, an expert in maternal and child health. The East Side also needs more providers.

Programs to reduce unplanned pregnancies, especially among teenagers, would also reduce the number of women getting late or no prenatal care.

While many cities are making efforts to get women into early prenatal care, it’s not an easy fix. “The issue is that most cities don’t have the kind of funding needed to address all the underlying factors at one time,” Bellinger said.

Prenatal care should be a priority for Bexar County, Sunil said.

“This is a huge problem in our society,” he said. “We need to address these issues to make sure women are in good health and make sure children are born in good health as well.”

[This story was originally published by San Antonio Express-News.]

Photos by Lisa Krantz/San Antonio Express-News.