‘Bereavement Deserts’: Amid a Rise in Parental Deaths, Grief in Children Is Often Overlooked

The story was originally published by MindSite News with support from our 2024 National Fellowship.

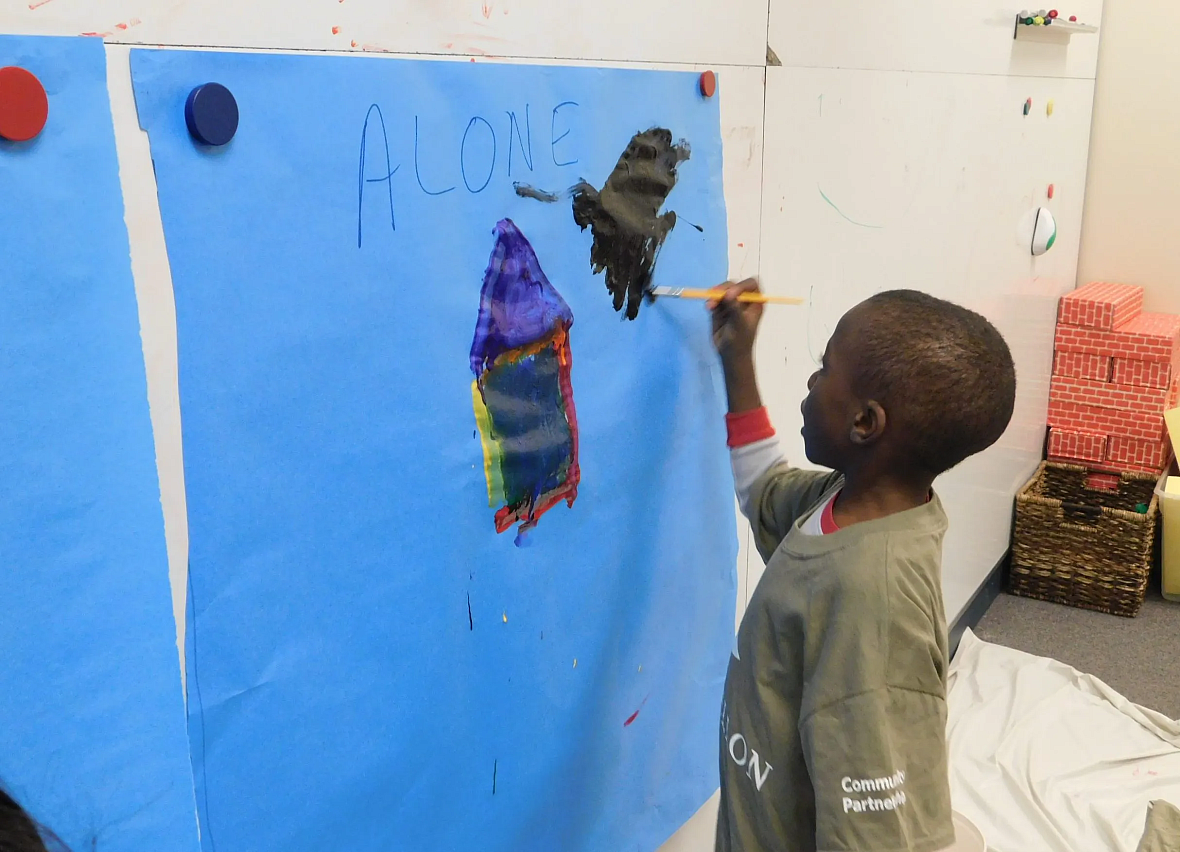

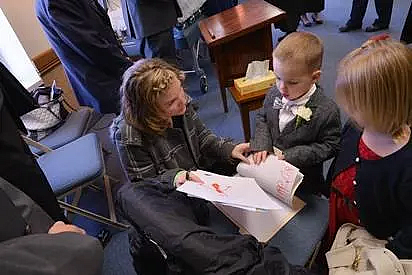

A young boy expresses his feelings through paint during a peer-support group session at Highmark Caring Place in Pittsburgh in 2023. Helping young children identify and talk about their feelings is a goal of the group sessions.

‘My son needed something I couldn’t give.’ Surviving parents seek grief support for kids

Amanda Joyce Jensen will always remember the night she told her 4-year-old son, Kezman, that his father, Marshall, had died of cancer – and how Kezman said he already knew because “Daddy came to me first.” He cried as he drew a picture of his dad standing at the end of the hallway, wearing a red superhero cape, flying into his thoughts.

The euphemisms that adults often use to soften the shock can be confusing to a child of such a young age – that someone is “lost” or “passed away” – so his mother talked with Kezman gently but directly. He grasped more clearly than she had imagined that his father was gone and never coming back.

Top: Jensen family together. Bottom, from left: Marshall Jensen rocking out (his band, the Kismets, won a Battle of the Bands competition in Salt Lake City before his diagnosis); a drawing by Kezman shows how he learned of his father’s death: he came to Kezman as a superhero. Bottom right: Kezman also loves to play guitar.

Family photos courtesy of Amanda Joyce Jensen

Heal Courageously, a Salt Lake City nonprofit that takes family photographs during their cancer journeys.

As life without Marshall stretched before them, Kezman’s grief emerged without words. He screamed like he was being tortured when she cut his hair or had sudden bursts of intense energy when she was trying to settle him down for bed. Sometimes she wasn’t sure if his behavior was typical of a 4-year-old boy or a signal of his grief.

Then one day his mother took Kezman to The Sharing Place, a child and family grief center in Salt Lake City, and he jumped into a pile of foam. There, in the Volcano Room, he also threw giant plastic balls against padded walls and climbed on pillows. In a playroom, he built contraptions with Legos, and in the art room he colored with markers. During each visit, he could talk about his dad in a circle with other young kids who’d lost a parent or sibling while Jensen met in a group with bereaved parents who also were struggling to recreate their lives.

The results were transformative. “My son needed something that I couldn’t give him,” she said. “I just noticed how much better he did in school, how much better he did socially, when he had a place where people understood a little more” what he’d gone through.

After two years, Jensen, a health coach, wanted to make a fresh start, so she and Kezman moved to the Mojave Desert town of St. George, near the red cliffs and dunes of southwest Utah. In St. George, there was no grief support group for children – it’s what some researchers are calling a “bereavement desert.” Instead, Jensen started driving back to The Sharing Place every other week – four hours each way – for about a year.

The trip was exhausting: She would pick Kezman up from kindergarten at 3 p.m. and rush there just in time for the sessions. Sometimes she drove the full distance back while Kezman slept in the car; other times she was too exhausted and stopped at a hotel.

Still, Amanda and Kezman were in some respects fortunate. Hundreds of thousands of children lose a parent in the U.S. each year, and most have no access to counseling or grief support groups. They may not even know such services exist.

Parental Deaths Soared During the Pandemic

The death of a parent is one of the most traumatic of the adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) that can derail emotional development and lead to long-term problems, including depression, behavioral issues, or academic problems in school. Child grief support and “resilient parenting” strategies can help protect against those bad outcomes – as evidenced in studies that followed children for as long as 15 years after the sudden loss of a parent.

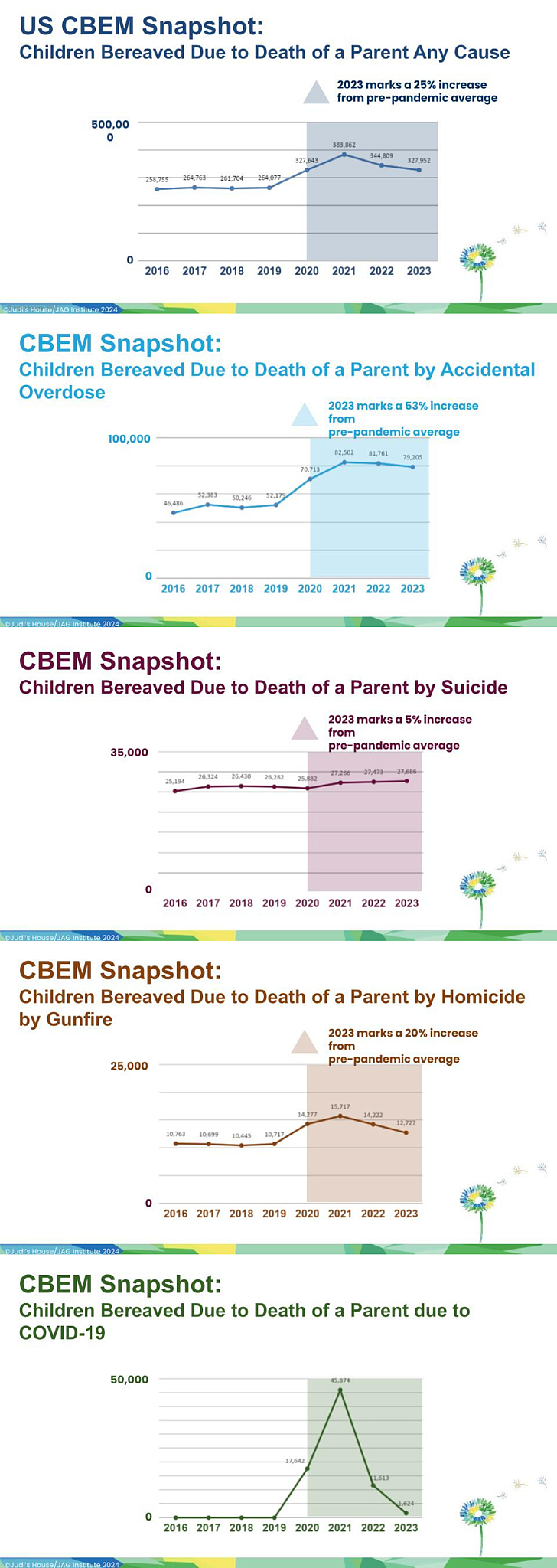

But even as the combination of COVID-19 and a steep rise in gun violence and drug overdoses pushed parental deaths up by 46% during the first two years of the pandemic, access to grief support failed to match the need. In 2021, an estimated 2.9 million U.S. children under the age of 18 – about 4.2% of all kids – had lost a parent or primary caregiver, according to a January 2025 analysis published in Nature Medicine. And each year, the toll of childhood bereavement grows: By the time they turn 18, almost one in 13 children – 5.4 million in all – will experience the death of a parent, according to 2024 estimates from the JAG Institute, a research initiative of Judi’s House, a grief center for children and families in Aurora, Colorado.

Some communities are even more severely impacted. One in six American Indian or Alaska Native children and one in nine African American children will experience the death of a parent before they turn 18, the JAG Institute estimates. Yet rural communities and communities of color often lack grief support centers that serve bereaved children and their families.

“There’s a great need, and we could be meeting that need but we’re not,” said Micki Burns, chief executive officer of Judi’s House. “And right now, unfortunately, the resources are hard to find.”

Identifying an opportunity for services

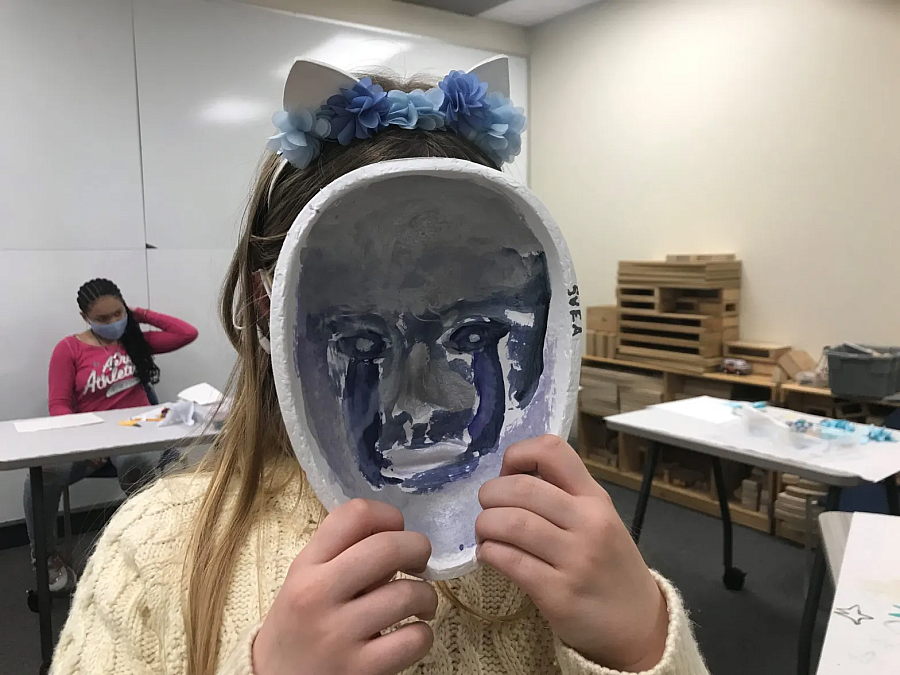

Supporting children through difficult feelings of grief helps them learn to integrate the loss into their lives. Here a child has painted the inside of a mask to show the feelings she is holding inside and not sharing with others.

Photo courtesy of Highmark Caring Place in Pittsburgh.

Bereaved children – the forgotten children left behind after the death of parents, caregivers, and other close family members – are rarely a part of the national conversation about gun violence, drug overdose deaths, deadly diseases or other health threats. Indeed, in most parts of the country, there is no system in place to identify children who have experienced the death of parents or other caregivers, so they can be offered services. In Utah, at least, that’s starting to change.

On July 25, 2023, Gov. Spencer Cox issued an executive order making Utah the first state to add a question on its death certificate form asking if the deceased person had surviving children. One year later, the state had identified 1,062 families with children under 18 who’d lost a parent or caregiver.

Children served by The Sharing Place create pipe-cleaner representations of the person that they lost as a way to honor them and process their grief.

Photo courtesy of The Sharing Place

Through a partnership with United Way, a team of outreach coordinators has begun reaching out to the families to connect them with counseling, grief groups and other resources.

“The goal is for these kids to have the opportunity to receive the services that they could and should be getting,” said Nate Winters, deputy director for operations at the Utah Department of Health and Human Services.

Photo courtesy of The Sharing Place, Salt Lake City

The teams will notify the families of a critical resource that bereaved children often miss out on: Social Security benefits. Surviving children of a deceased parent are eligible for a monthly benefit based on that parent’s previous earnings, but only about 45% of them apply and receive it, according to a 2019 analysis by David Weaver, a statistician and economist at the University of South Carolina. Those who don’t apply are forgoing a benefit with an average monthly value of $1,441 per family in 2024 – an amount that could make a big difference to families struggling with a loss of income amid their grief.

The Utah effort aims to create a model that other states can replicate. It is spearheaded by the Children’s Collaborative for Healing and Support, a nonprofit organization that aims to develop support networks for families that have experienced the death of a parent or caregiver. The collaborative worked with the Granite School System in Salt Lake County to add a question about bereavement to annual school registration forms as another way to identify grieving children.

Now the Collaborative is working with partners to create similar systems across the country that can identify bereaved children, connect them with financial assistance, and provide them with grief support.

The economic cost of childhood grief

Most grieving kids can be helped with a peer-support model similar to what Kezman Jensen received. That support reduces the risk that they’ll develop depression, learning problems and other academic, social or emotional difficulties. Behavioral changes after the death of a parent or other close family member can also include withdrawal, bursts of anger, or dangerous risk-taking. Roughly one in 10 children will experience “complicated grief” that is intense, persistent and disruptive and requires treatment from a mental health professional.

A circle of children and caregivers at the Sharing Place in Salt Lake City in 2019. Participants give their name, the name of the person they’re grieving and how they died, and then they share something about that person.

Photo courtesy of The Sharing Place

Grief ripples through families and communities, but the failure to support bereaved children has a much wider impact, said Catherine Jaynes, president and CEO of the Children’s Collaborative. “For states and localities to not take care of these children, what is the economic cost?” she said. “What is the cost to the children that are impacted from an education perspective, from an incarceration perspective, from an earnings perspective?”

A variety of studies show that children who have experienced the death of a parent are less likely to attain a college degree or even to graduate from high school. Black and Native American children have the highest rates of parental loss, so their educational prospects are disproportionately affected – an outcome that University of Minnesota researchers highlighted as “a form of structural racism.” Over their lifetimes, children who drop out and don’t get a high school diploma earn about $1.6 million less than those who obtain a bachelor’s degree. Collectively, that means bereaved children lose billions of dollars in lifetime earnings.

The burden of bereavement deserts

Lucas Edward Campbell was 13 years old when his mother died in March 2015 after waging a years-long battle with cervical cancer. What he felt, beyond his grief, was alone. He didn’t know a single person at his school who had gone through a similar loss.

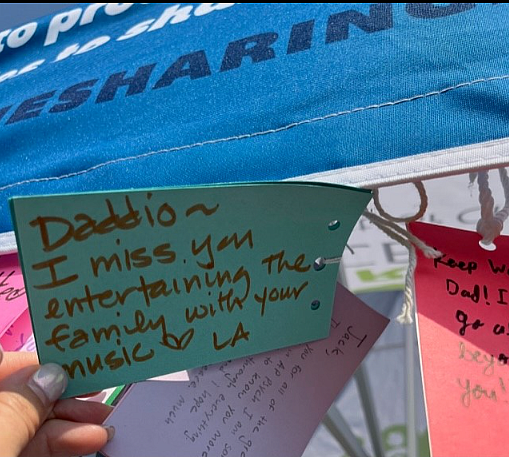

A written tribute left by a teen for their father.

Photo courtesy of The Sharing Place, Salt Lake City.

At Ele’s Place, a center for grieving children and teens in Ann Arbor, Michigan, he found the connection he was yearning for. In one activity, the teen group decorated paper maché masks. On the outside, he painted a smiling face. Then the teens wrote what they were feeling on the inside. Lucas wrote “lonely.”

“I realized a lot of these people are hiding the same things I’m hiding. I realized I’m not alone in this, what I’m feeling is OK,” said Lucas, now 23 and a volunteer at the center. “That is a very powerful memory that I have.”

The need for connection has been the catalyst for grief centers serving children and families; they often are launched by someone who was impacted by loss as a child or by a parent who couldn’t find help for their own grieving children. The National Alliance for Children’s Grief lists more than 400 locations that offer some form of peer-based grief support, including camps, centers, or hospice programs. The New York Life Foundation, the leading funder of family grief centers, spent about $8 million on child bereavement programs in 2023, enabling services to be provided free of charge.

Still, while grief centers do their best to meet the demand, even expanding with satellite locations, communities with the highest rates of parental deaths often lack the resources to help the children left behind.

Michigan aims to change that. In June, the state launched a website that enables users to search for grief support and other bereavement resources by ZIP code. HopeHQ, a joint project of Wayne State University and the University of Michigan, provides information on resources for grieving children and their caregivers who have experienced the death of a parent or family member from a drug overdose.

The next step is to identify bereaved kids – and find “bereavement service deserts,” a term two researchers, Luisa Kcomt and Sean Esteban McCabe, use to describe places where grieving children and their families have few or no local resources. Kcomt, an assistant professor of social work at Wayne State, and McCabe, director of the University of Michigan Center for the Study of Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking, and Health, are mapping parental deaths from drug overdoses and other causes of death by matching names on birth and death certificates, then overlaying that with programs that serve bereaved children and families in each county.

“We really need to know where those deserts are, so that we can reach them and deliver services that will improve their health,” McCabe said. “The quality of bereavement services should not be determined by the ZIP code where you live.”

Children at Highmark Caring Place in Pittsburgh take part in activities to honor the memory of the person they lost and work though their grief.

Courtesy of Highmark Caring Place.

Their work mirrors a project in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, home to Pittsburgh and surrounding suburbs. The county tracks and maps overdose deaths on a dashboard, and it has an integrated data system that includes child welfare and mental health services.

By matching parents’ names on death and birth certificates, county analysts reviewed records of children who lost parents to overdose between 2017 and 2022 during a five-year period. For many of these vulnerable kids, the loss upended their lives: While one in 14 were already involved with the child welfare system when their parent died, that number doubled to one in seven after five years, according to data provided by Allegheny County to MindSite News.

For children left behind after a parent’s drug overdose, their use of mental health services rose for about six to nine months after the death and then returned to prior levels, an indication that their issues were treated with a short duration of therapy, said Erin Dalton, director of the Allegheny County Department of Human Services. The Allegheny analysts also looked at parental deaths due to homicide and suicide and found that children whose parents died by homicide were more likely to be Black and were much younger than those whose parents died of overdoses, Dalton said.

She said the department only offered grief support to children who were already involved with the child welfare system or other county services. “We have not taken the step of reaching out proactively to everyone who has lost a parent,” she said – due partly to concerns that families may be alarmed to be contacted by the county department that also runs child protective services.

Adults don’t want to talk about grief

There’s another inherent barrier in offering support: Adults often treat death like a taboo topic. “Children’s grief is really very poignant. They tend to ask questions that we don’t want to think about,” said David Schonfeld, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician who directs the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Avoidance might stop the questions, but it also interferes with the grieving process, he said. “You can’t cope with something you don’t talk about or understand,” he said.

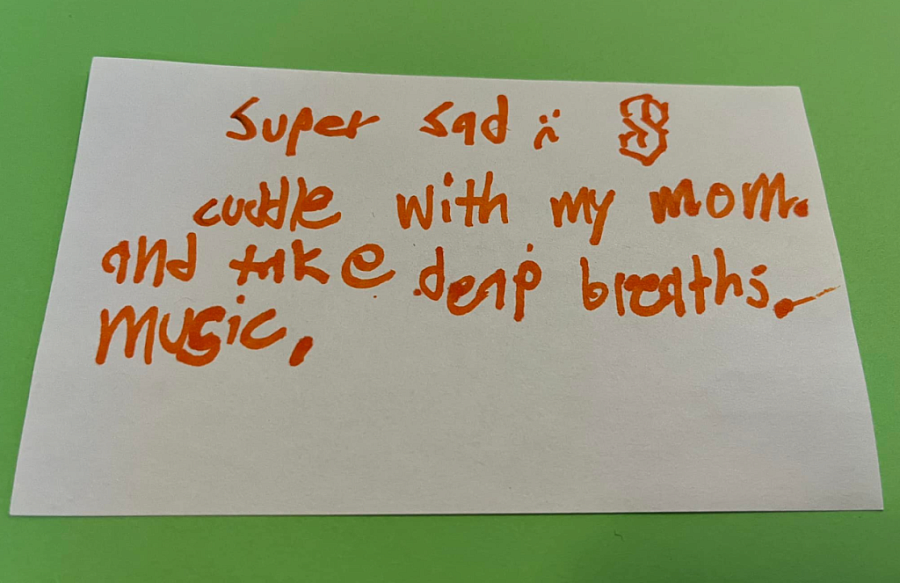

Feelings of sadness and loss expressed by a child.

Photo courtesy of The Sharing Place

At the Kentucky Center for Grieving Children and Families in Lexington, clinical program manager Emily Johnson seeks to open up conversation. “I always wanted to do something to help people who are grieving, especially kids and young adults, just because I feel like that gets kind of forgotten about,” said Johnson, a marriage and family therapist. “For the longest time, people had the notion that kids don’t grieve, or we (shouldn’t) talk about sad things with kids.”

She knows from personal experience that isn’t true. She was 11 when her father was diagnosed with cancer and 19 when he died. She was in college then, and her friends tried to be supportive – but they were living their best life while she was grieving.

“It almost felt like I was on a completely different planet,” she said, “like reality hit me in a different way than it had my peers. Sometimes I just felt disconnected because I was much more aware of life and death and what can happen.”

At the grief center, Johnson guides young children to work out their anger and sadness through play therapy. They decorate boxes to be “worry monsters” that eat their worries, which are written on pieces of paper and fed through a slit.

She also trains local teachers and counselors to work with bereaved kids. Indeed, schools are a primary site for grief support. The Grief-Sensitive School Initiative, sponsored by the New York Life Foundation, provides grief support resources and small grants to about 5,300 schools around the country. Schonfeld’s national center responds to crises such as school shootings and natural disasters such as wildfires, and also offers online teacher training modules, public presentations on how to support grieving children, and free in-person training to some districts participating in the initiative. Requests grew during the pandemic: In New York City alone, he provided virtual training for about 20,000 educators and counselors in how to support grieving students.

The initiative is now expanding to additional districts, after-school programs and youth-serving organizations such as the Boys & Girls Clubs of America. “We want to make sure that every adult that is working with children and cares about children knows about the (grief support) resources available to them,” said Heather Nesle, president of the New York Life Foundation.

Using art to work through grief.

Photo courtesy of The Sharing Place, Salt Lake City.

About 4,000 employees and life insurance agents help spread the word, working as “ambassadors” to share grief resources with their local schools and raising money to support child bereavement programs, including grief support camps.

The foundation’s 2024 State of Grief Report documents the need: Almost two-thirds of teachers surveyed said they “personally have seen the negative impacts of grief on children in their classrooms.” In January 2024, the New Jersey legislature passed a law adding grief education to the health education curriculum for grades 8 to 12. Maryland, Connecticut, and Massachusetts have similar policies.

Schonfeld also trains pediatricians in developmentally appropriate ways to help children cope with grief and death, as does the Grief-Sensitive Healthcare Project at the Yale Child Study Center.

‘Families Are Forever’

Back in Salt Lake City, The Sharing Place is bustling. In one room, kids are drawing and sculpting. In another they make dinner at the toy kitchen or act out family life at a dollhouse. Upstairs, teens are engaged in a game of Jeopardy. But the pictures they draw reflect their loss. The Jeopardy game is designed to help teens talk about their grief. A writing wall pays tribute in simple words: Dad was nice. Families are forever. Here, children can act out their feelings, speaking aloud words they wish they could say to a parent or sibling who died.

There’s a waiting list to get a spot in a child grief support group, even though three locations in Utah offer a total of 31 biweekly groups for children ages 3 to 18 – and parallel groups for parents or caregivers. About 120 volunteers work alongside group coordinators, helping to guide the activities and circle time, where children and teens hold a “talking stick” and share what they miss about someone, what happy memories they have, what they regret, what makes them feel angry.

About 22% of the families come from outside Salt Lake County to attend grief programs, some driving an hour or more. Executive director John Gold is exploring the possibility of opening a center in St. George, where Amanda and Kezman Jensen live. There are other families who need support there who can’t make the drive as they did. “It’s my mission and the board’s mission to make this a statewide organization because the need is so great,” Gold said.

At his father’s funeral, then 4-year-old Kezman Jensen showed his mother which drawings he wanted to place in his father’s casket.

Photo courtesy of Amanda Joyce Jensen

Today Kezman is 13 and in 8th grade. His mom marvels at how much he resembles his father – not just physically, but in his spirit and talents. He plays guitar and writes songs, works hard at school, and helps his mother at events that raise money for cancer research and services. “His father was a really good man, and he is a good kid,” she said.

The time Kezman spent at The Sharing Place from the age of 4 to 7 helped him learn that he was not alone in his loss. “(He realized) there’s a lot of people that go through hard things, and they have different lives than they felt that they would. He just handles it really well,” said Jensen, who wrote an inspirational memoir based on her experiences, called Marshalling Beats of Your Heart.

Jensen and her son recently went to a fundraising event for The Sharing Place, and she promised Gold she would do what she could to help him bring his program to St. George so that other families can benefit. “I just can’t be more grateful for having what we did have at a time when we needed it so much,” she said.22