News of her pregnancy led to her breaking up with her child’s father. The extreme fatigue that she experienced during her first and second trimesters meant working full time was nearly impossible, and she was terminated from her job. She had weird pains that brought her to the emergency room during her second trimester. Without a stable income, she struggled to feed herself and her 8-year-old daughter. McIntyre would miss meals to save money and to afford to pay rent in a moldy Ward 5 apartment.

She was able to find temporary work at a biotech company in Maryland. But the commute was a strain on her physical and mental health. She still had to drop her daughter off at school and sometimes had to pick her up, too. “I worked there from June to November and that’s when I started having a lot of complications with my health. I just wasn’t feeling good. It was like every day. It was a drag and I was barely walking,” she says.

In October, she had to resign. The fatigue and other pregnancy-related sicknesses were just too much.

McIntyre’s baby, Kenni Nyelle, was due Dec. 17. But by Nov. 30, McIntyre was in such unbearable pain she had to sleep on all fours on the floor of her apartment. She called for medical advice. “The nurse was like, ‘Well, are you bleeding?’ I said, ‘No, just increased pain.’ So shortly after I hung up, I went to the bathroom and there was blood.”

McIntyre drove herself to MedStar Washington Hospital Center, terrified about what was to come, and her fears were quickly confirmed. There was no heartbeat. Kenni had died in utero.

“I didn’t really care for the way I was treated. It was just so different,” McIntyre says about her hospital experience. “The doctor didn’t even seem to try and find a heartbeat. I had to push the baby out with no anesthesia. The doctor literally stuck her whole hand inside of me and was pulling out [parts of the placenta]. She didn’t even warn me about what was going to happen. I was screaming in pain. That was actually worse than the delivery.”

A spokesperson from MedStar Washington Hospital Center declined to comment on McIntyre’s case due to patient privacy laws. In an emailed statement, the spokesperson says, “we’d like to offer our condolences to Ms. McIntyre for her loss.”

Trying to explain what happened to her daughter, who was anxiously awaiting her new little sister’s arrival, compounded the devastation for McIntyre. “She just started breaking down crying as soon as I told her. It was bad. She was so confused,” she says.

Now, McIntyre is trying to piece her life together. Finding therapy for her and her daughter has been her biggest challenge.

“Every therapist I went to, or program I went to, they don’t have enough therapists and there’s a waiting list,” McIntyre says. “I don’t understand. If somebody just went through a death like this, there aren’t enough licensed therapists. But if somebody gets murdered, you find therapy for [their families]? You even help them move? To me, that’s crazy.”

Many families in D.C. and across the country are confronting the tragedy of fetal death. It is often difficult to determine a single cause of death, and the potential reasons can be wide-ranging, if they are known at all.

According to the data from the 2022 National Vital Statistics Report, Black families nationwide were among the highest risk of experiencing a stillbirth in 2020 (10.34 per 100,000) as compared to non-Hispanic Asian families (3.93 per 100,000) and non-Hispanic White families (4.73 per 100,000). The District has the fourth highest fetal mortality rate among the jurisdictions that reported data from 2019 to 2021 at 5.38 deaths per 1,000 compared to the national rate of 3.66. Yet the city has no public health campaigns to educate parents about stillbirth.

So what do Black parents need to know?

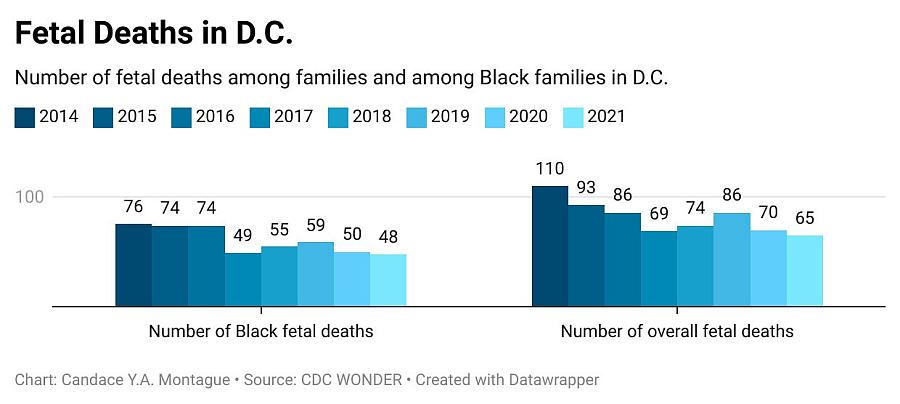

A fetal death occurs after at least 20 weeks of gestation or if the fetus weighs at least 500 grams (about 1 pound). The death is determined by the status of the fetus when it is delivered from the mother’s body (either through vaginal or cesarean birth) and shows no sign of life: no heartbeat, no breathing, no movement of voluntary muscles. DC Health submits fetal death data to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and publishes the death data in a “Pregnancy Outcomes” report. But there is some discrepancy between the two. The most recent DC Health report was published in 2017 and shows that there were 63 fetal deaths among Black families versus three from White families, three from Asian families, and eight from Hispanic families in 2015. But CDC data shows 74 fetal deaths in Black families that year.

No DC Health report beyond 2017 mentions fetal death, and the agency has not responded to City Paper’s repeated requests for comment on this, and other questions. But CDC data on fetal death in the District paints a grim picture.

Fetal deaths overall in the U.S. have declined in the past 15 years. In 2011, there was an 8 percent decline in rates among non-Hispanic Black women throughout the U.S., but D.C. saw no significant change that year. For more than a decade, D.C.’s Black stillbirths have consistently remained above the national average.

Elizabeth O’Donnell had a stillbirth in December 2020. The former DC Public Schools teacher was denied paid family leave after the death of her daughter, Aaliyah. When she posted on social media about her disgust with the way the school system disregarded her need for time off to heal, she soon discovered she was not alone. “I got the most feedback when all the paid family leave stuff happened,” O’Donnell says. “I mean, hundreds of people DMing me or finding my work email and emailing me saying, ‘I’ve had a stillbirth, too, and I live in D.C.’ I was blown away.”

O’Donnell, who lives in Anacostia, founded the nonprofit Aaliyah in Action the year after her daughter’s death to support families who have experienced perinatal, neonatal loss, or infant death. She visits the labor and delivery departments of area hospitals to hand out self-care packages for parents who are experiencing loss. “In the past year, I’ve given at least 30 to 40 packages to Washington Hospital Center alone,” she says.

Parents who experience a fetal loss can request a fetal death certificate from DC Health’s vital records’ division. The certificate will list the name, date of death, and cause of death, if determined, and it is a permanent legal record that can be used to track perinatal losses. The data from these certificates can also be used to help public health officials improve obstetric care. O’Donnell is skeptical that those analyses are being done on a consistent basis.

O’Donnell has also joined forces with PUSH for Empowered Pregnancy, an advocacy organization working to end stillbirths across the country. The not-for-profit organization is pushing for more action to occur on the federal level. There are currently two pieces of legislation before Congress. The Stillbirth Health Improvement and Education (SHINE) for Autumn Act was introduced in July. If passed, the bill would create a federal-state partnership that would invest in research, bolster awareness, and improve data collection from stillbirths.

The Maternal and Child Health Stillbirth Prevention Act is a bipartisan bill that was also introduced in July and would support stillbirth prevention and research. If it passes, this bill will allow states to use federal grants for prevention efforts such as more educational campaigns.

Samantha Banerjee, executive director for PUSH, says that these laws will help with consistency in data collection and funding.

“These issues that you’re seeing with data collection, that you’re seeing in D.C., are happening all over the country,” Banerjee says. “Some states are filling out this record by hand. It might be somebody in the hospital who may or may not know what they’re doing.”

One program that could make a difference is Count the Kicks, an app and program designed to help expectant parents keep track of the number and frequency of kicks from the fetus starting in the third trimester. Counting fetal movement has been shown to help monitor fetal activity and development while combating adverse perinatal outcomes. The app is free and available in 16 languages.

Christine Tucker, health equity coordinator for Count the Kicks, touts many successes in lowering stillbirths in Iowa and says those efforts can be duplicated in other states. “We have successfully lowered the rate of stillbirth in Iowa by 32 percent for the general population and 39 percent for Black families, which is important because they are disproportionately affected by stillbirth in the U.S.” Tucker says. “So we know that we have a solution. We just want to get it into the hands of as many people as possible.”

The app is listed on the DC Maternal and Infant Health Summit website as a resource for expectant parents to use. But there is no official partnership between the Count the Kicks and the health department. Tucker says Count the Kicks has established partnerships with Maryland and Virginia, but D.C. has not agreed to one yet. “We have had discussions with the Health Department [in D.C.],” Tucker says. “We’d love to create some sort of a partnership in Washington, D.C. But we’re not there quite yet.”

Partnership or not, D.C. families are still able to use the app to keep track of their babies’ movements. Tucker says she’s encouraged by the fact that this app is still accessible to everyone.

“We would love for any families in Washington, D.C., to check it out and use it to get to know their babies’ normal [movements] and speak up to their providers if they notice a change in movement,” Tucker says.