Can Montana mend its racial gap in foster care?

The story was originally published by the Montana Free Press with support from our 2023 Data Fellowship.

Children play in a park on the Crow Reservation on Jan. 3, 2024.

Tailyr Irvine / MTFP

In light of the 2023 U.S. Supreme Court decision that upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act, and as a reckoning with the traumatic legacy of federal Indian boarding schools continues to spread, more attention is being paid nationwide and in Montana to the existential threat that the removal of Native American children from their families poses to Native American communities.

It’s not clear, however, how that growing awareness might change one of the defining characteristics of Montana’s foster care system. As the available data documents, Native American children in Montana have long been and remain dramatically overrepresented in foster care, and are separated from their families at a significantly higher rate than white children. Child welfare experts say that pattern is devastating for many parents, children and tribal nations, but difficult to change.

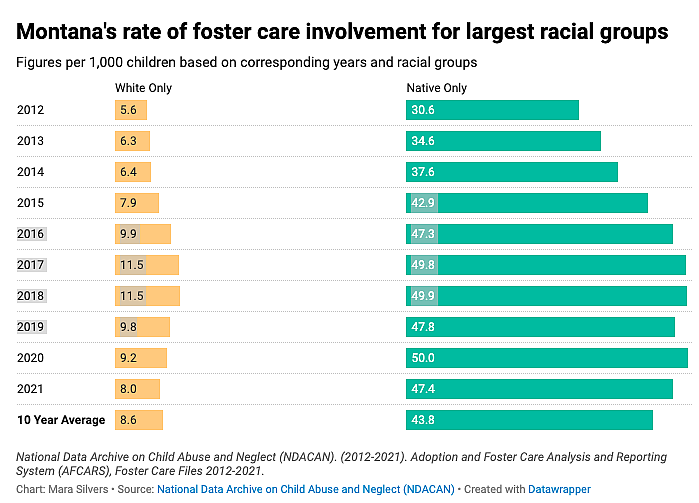

In cases handled most often by the state, but sometimes by tribal authorities, Native children are involved in out-of-home foster care placements at roughly five times the rate of white children, according to a Montana Free Press analysis of federal data collected between 2012 and 2021, the most recent decade for which data is available. During that span, the recorded number of children in Montana’s end-of-year foster care caseload ranged from a 2012 low of 1,937 to a 2018 high of 3,946.

Among the states with the largest proportions of Native American citizens, Montana has one of the largest percentages of Native children in foster care, according to a 2023 analysis by the national research organization Child Trends. A review of 2021 state caseload data by the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges recorded that Native Americans in Montana are more overrepresented in foster care than any other racial group in the state based on population.

We know that racism exists in child welfare systems, but it also is the creator of all the factors that bring families into the systems over time.

DR. DEANA AROUND HIM, RESEARCHER, CHILD TRENDS

Child welfare experts say the skewed number of Native children in foster care stems from both unequal access to economic opportunity and health care resources in Native communities and deeply rooted biases held by child protection authorities about what safe and stable families look like.

“We know that racism exists in child welfare systems, but it also is the creator of all the factors that bring families into the systems over time,” said Dr. Deana Around Him, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and researcher at Child Trends.

The racial gap in Montana is particularly striking when described at a smaller scale. While an average of roughly 9 out of 1,000 white children in Montana were in foster care over the last 10 years, Native children appeared at a much higher rate, with an average of 44 of every 1,000 spending time in the system, according to MTFP’s review of the available federal data.

And those figures are likely an undercount, arising from gaps in data collection by local, state, tribal and federal child welfare agencies. The federal database used to track state-level foster care trends relies primarily on information from the Montana Department of Health and Human Services, which operates the largest child protective system in the state. It does not include comprehensive reports from tribes, which, as sovereign nations, operate their own child welfare programs and adjudicate cases in tribal court, or from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which handles a portion of child abuse and neglect investigations and foster care placements for some tribal nations. That federal agency acknowledged but did not provide answers to a list of questions submitted two months before our February publication date about the caseloads its workers handle through contracts with various tribal nations.

While foster care is designed to protect children from abuse and neglect, jointly defined in Montana statute as “actual physical or psychological harm to a child” or “substantial risk of physical or psychological harm to a child,” child welfare experts also recognize that removing children from their families or caretakers can be traumatic and deeply destabilizing.

In recent years, national child welfare authorities and policy researchers have pushed states to focus on keeping children safely in their homes by providing more resources, support and guidance for parents. Montana has reduced its overall foster care caseload since 2018, but the disproprotionate representation of Native Americans remains, continuing a damaging cycle of family separations in Indigenous communities.

“You think about the future of your nation, nation building, hope for the future,” said Dr. Maegan Rides At The Door, an enrolled member of the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes of the Fort Peck Reservation, descendent of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, and co-founder of the National Native Children’s Trauma Center, based in Missoula. “What does our future look like? How can we continue to revitalize our culture if we don’t have our kids here?”

Lesa Evers, the recently retired tribal relations manager with the state Department of Public Health and Human Services, called the overrepresentation of Native children in foster care “unacceptable” in a December interview. But, she said, publicly acknowledging and addressing it has not been a consistent priority for state health officials, and tribal governments are often focused on child welfare work at a local level rather than statewide solutions.

Evers, a member of the Little Shell Tribe and a Blackfeet descendent, said that while the issue spans jurisdictions and is inherently complicated, the overrepresentation of Native children in the state’s caseload can’t be solved without the health department’s focused attention.

“They’re aware of it,” Evers said about state officials. “Why is it not alarming? And if it’s alarming, why are we not addressing it?”

There are no demographic breakdowns of the state’s out-of-home placements on the health department’s public-facing foster care dashboard. The state does not publish regular reports about case outcomes such as reunification, adoption, long-term guardianship, or kinship placements for Native or non-Native youth, though some of that information is available through federal reports. The state also does not collect or publish data about the number of cases it handles that are subject to the provisions of the Indian Child Welfare Act, the federal law that requires collaboration between state and tribal governments on child welfare cases involving tribal members that originate outside of tribal jurisdiction.

They’re aware of it. Why is it not alarming? And if it’s alarming, why are we not addressing it?

LESA EVERS, RECENTLY RETIRED TRIBAL RELATIONS MANAGER WITH THE STATE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

“MT currently has minimal data available to analyze disparities or disproportionalities in either race or other historically underserved populations,” notes a 2023 assessment by the state health department’s Child and Family Services Division. It later states that, in April of the prior year, Native Americans comprised more than 38% of the foster care caseload.

“The disproportionality of Native American children in Montana’s foster care system is a longstanding problem,” the report continues. “There are many factors contributing to this including socioeconomics, access to physical and mental health services and historical trauma which is primarily the result of historical governmental policies dictating the treatment of Native American children and families. CFSD cannot address all these issues.”

In a December interview, Nikki Grossberg, administrator of DPHHS’ Child and Family Services Division, also acknowledged the problem of Native overrepresentation but emphasized that the state, which employed 172 child protection specialists throughout 2023 and handles thousands of reports of child mistreatment annually, is not the only entity with a responsibility to address an issue spanning multiple jurisdictions and professions.

“I think it's really about continuing to have the conversation,” Grossberg said. “And with the whole system, right? So really talking with the judges, the attorneys, our providers. One, to acknowledge it, make sure we know what's out there, and two, to bring people together, to really help try to figure out, you know, the ‘why’ and then ‘how do we do what.’”

Sunrise illuminates Pioneer Park in Billings on Jan. 3, 2024.

Tailyr Irvine

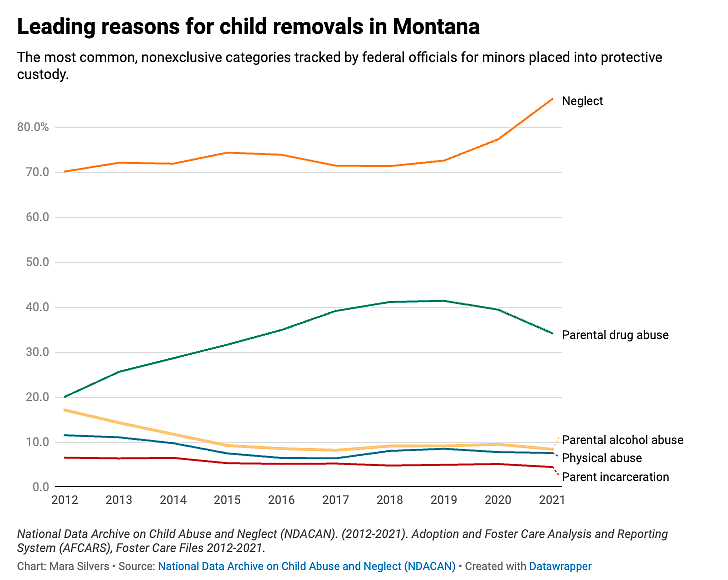

Neglect, an overarching category that can include many types of physical and psychological maltreatment, is the most common factor associated with a child of any racial group entering foster care in Montana. That reason, sometimes in combination with other factors, was listed by child protective workers in an average of about 73% of all cases over the decade’s worth of data analyzed by MTFP, reaching nearly 85% in 2021. Physical abuse, by comparison, was cited much less frequently, appearing in an average of about 7% of foster care cases involving Native children, and 10% of those involving non-Native children, over the past decade.

While the broad category of “neglect” often co-exists with conditions of poverty, unemployment or parental addiction, researchers at Child Trends have pointed out that exposure to those risk factors does not mean a child will experience neglect or abuse — one of the common myths about the child welfare system.

“Certainly, while poverty does not make one a bad parent and does not equate with abuse and neglect, poverty does expose family members' kids to risks of involvement with the child welfare system,” Kelly Driscoll, head of the Family Defense Bureau within the Office of State Public Defender, said at a January meeting of a legislative group studying the state’s child welfare system. “My kids can look like total street urchins and I'm given some deference as a highly educated white woman in Montana. Poor parents, Native parents, are sometimes not treated with that deferential treatment.”

Determinations of whether a child is being neglected, or is at risk of neglect, are often influenced by the subjective viewpoints of individual child protection workers, said Rides At The Door, of the National Native Children’s Trauma Center. Despite agency efforts to standardize the investigation process, she said, personal lenses are inevitably applied to determinations of safety.

“‘Oh, this child doesn’t even have their own bed, their own room.’ How are they assessing things? How are they determining neglect, unsafe environments?” she said. “And that gets to bias … It’s not just these systemic things.”

... I'm given some deference as a highly educated white woman in Montana. Poor parents, Native parents, are sometimes not treated with that deferential treatment.

KELLY DRISCOLL, HEAD OF THE FAMILY DEFENSE BUREAU, OFFICE OF STATE PUBLIC DEFENDER

In response to questions from MTFP, the state health department in November said it regularly trains caseworkers how to detect and avoid personal biases of all sorts in their decision-making and standardizes removal procedures statewide to insulate the processes from personal opinions. Other mandatory training for child protection workers focuses on compliance with the Indian Child Welfare Act and trauma-informed practices specific to racial minorities, department spokesperson Jon Ebelt said.

Parental drug use is another removal factor that has been more commonly listed in the last decade for Natives and non-Natives alike as Montana’s population struggles with addiction, rising rates of drug-related deaths and inadequate treatment options. Drug abuse was cited as a factor in an average of about 42% of Native family separations between 2012 and 2021, compared to 28% of cases involving non-Natives.

Child welfare researchers and advocates say addiction and mental health issues are often symptomatic of generational trauma in Native communities resulting from centuries of colonization and violence, including the suppression of Indigenous languages and cultural ceremonies. As recently as the 1950s and 1960s, tribal members were still directly experiencing the abuses of the Indian boarding school era, when Native children were separated from their families by federal workers and sent to non-Native institutions designed by the U.S. government to erase cultural identity and force assimilation.

Dr. Maegan Rides At The Door, a cofounder of the National Native Children’s Trauma Center, poses for a portrait in her office at the University of Montana on Jan. 9, 2024.

Tailyr Irvine / MTFP

Many tribal members interviewed by MTFP referenced that painful history as being closely linked to high rates of foster care involvement in their communities.

“When you look at being an Indian, our historical legacy is children being taken from us,” said Paula Bighorn, deputy director of the Fort Peck Tribes’ Health Promotion and Disease Prevention program, in a December interview.

Bighorn also reflected on the systemic challenges that make the modern-day problem of Native family separation hard to solve. Having worked as a child protection specialist for the state and for her tribal government before taking her current job, Bighorn described seeing how social and economic barriers can work against keeping children safely in their homes or connected to family networks.

“Are there jobs here? Is there housing here?” Bighorn said, raising examples of challenges facing families on the Fort Peck Reservation in the largely rural northeastern corner of Montana. “Those are two of the main things that you need to get your kids back, is housing and a job.”

Resource disparities and risk factors for child neglect and abuse are also present in more urban, resource-dense parts of Montana, where racial disproportionality in foster care involvement continues. Between 2018 and 2022, an average of 119 Native American youth living in Cascade County, which includes Great Falls, were in foster care at the end of each calendar year, compared to the average of 156 white children in foster care, according to state health department data examined by MTFP. Those figures don’t reflect the county’s demographics, which show that roughly 6% of the county’s under-19 population is Native, and 82% is white, according to population data collected by the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count Data Center.

In Yellowstone County, home to Billings, about 83% of the youth and teen population is white, and about 9% is Native American. But the county’s foster care caseloads tilt toward Native overrepresentation, with a five-year average of about 200 Native children in end-of-year care, compared to 355 white children.

Grossberg, from the state health department, attributed the high representation of Native children in Cascade and Yellowstone counties to proximity to reservations — the Blackfeet, Rocky Boy’s and Fort Belknap reservations north and east of Great Falls, and the Crow and Northern Cheyenne reservations east of Billings, respectively — and the frequency with which families move between the reservations and nearby cities.

When you look at being an Indian, our historical legacy is children being taken from us.

PAULA BIGHORN, DEPUTY DIRECTOR, HEALTH PROMOTION AND DISEASE PREVENTION PROGRAM, FORT PECK TRIBES

When asked, Grossberg said it would be possible for the state to track racial disproportionality in each of the child welfare division’s six regions, but that the department has not done so.

“We know it,” Grossberg said about the persistent racial imbalance in foster care. “For us, it's more about the energy of how we work on it than, you know, where that happens.”

Asked if she thinks the racial gap in Montana’s foster care system can be closed, Grossberg said yes, and referenced the importance of lowering health care and economic barriers in Native communities. Speaking about early intervention services, she said the department is trying to increase its outreach to local Urban Indian Health Centers in multiple cities to make sure culturally appropriate health services are available where families need them. She also said her team is working to make voluntary custody agreements with the child welfare division more accessible to Native families that are struggling, rather than waiting for a situation to escalate and trigger an involuntary child removal.

Grossberg indicated that rather than developing specific initiatives designed to prevent Native family separations, the department is trying to ensure that all families, regardless of race, have access to the resources they need to succeed.

The sun rises over Billings, on Jan. 3, 2024.

Tailyr Irvine / MTFP

“[We focus on] providing the families, Native or non-Native, all the same efforts we do to try to prevent removal,” Grossberg said. “It's not like we're going to separate it out and say, ‘Do something different,’” she said.

Grossberg also said the state will stay involved in discussions about racial disproportionality in foster care, such as the Moving the Dial initiative organized by the state judiciary, especially when there’s an opportunity for collaboration with tribal nations and state or tribal court systems.

“The conversation is not going away. It's something that all states, including Montana, need to really focus on and continue to work and address. And I think we do that by engaging our tribal partners to figure out and find solutions,” Grossberg said.

Evers, who worked in tribal relations with the state for more than a decade under the administrations of governors Brian Schweitzer and Steve Bullock, said bringing change to large-scale problems affecting Native communities requires sustained and explicit effort. She said state officials were more focused on understanding Native overrepresentation in foster care in 2019, when the issue was studied by the State-Tribal Relations Interim Committee, resulting in a report about the need to improve communication between state and tribal governments about ICWA cases. Since then, she said, the state’s attention has drifted.

The conversation is not going away. It's something that all states, including Montana, need to really focus on and continue to work and address.

NIKKI GROSSBERG, DIRECTOR, CHILD AND FAMILY SERVICES DIVISION OF THE MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Since Evers’ retirement last year, the health department has decided to merge the position of tribal relations manager with that of the director of American Indian health. Last summer, another department employee left a position responsible for managing the state’s compliance with ICWA. Grossberg said the agency is updating that job description to include other responsibilities related child welfare, tribal relations, and disproportionality, and aims to post that position in March.

Evers acknowledged the complex challenge of changing the racial makeup of foster care in Montana. But the longer an uneven pattern of family separations continues, Evers said, the harder it is to create trusting and collaborative relationships between Native communities and the state child protection system. If the status quo doesn’t change, generations of family members will keep growing up apart from one another, a profound loss that ripples across communities and is difficult to convey with data. Responding to that problem should trigger more engagement from all parties, including the state, Evers said, not less.

“Any issue can be resolved if you start breaking it down into doable pieces,” she said. “It requires commitment and acknowledgment that there is an issue.”