Children In Crisis: Caring for foster kids, doctors find long reach of neglect, abuse

Kristin Gourlay covers health care for Rhode Island Public Radio, Rhode Island's NPR station. Her series “Children in Crisis” examines the problems at Rhode Island's child welfare agency, attempts to fix them, and the impacts on children, families, and caseworkers. From the difficulties of providing quality health care to foster children to the lack of foster families willing to take in teenagers, Gourlay finds a system – and the children it’s charged with protecting – in crisis.

Other stories in the series include:

Children who experience abuse or neglect–or even the stress of poverty—can have serious health problems later in life. That’s one of many challenges for children in Rhode Island’s child welfare system. We continue our series “Children in Crisis” with this look at how some health care professionals hope to address those challenges.

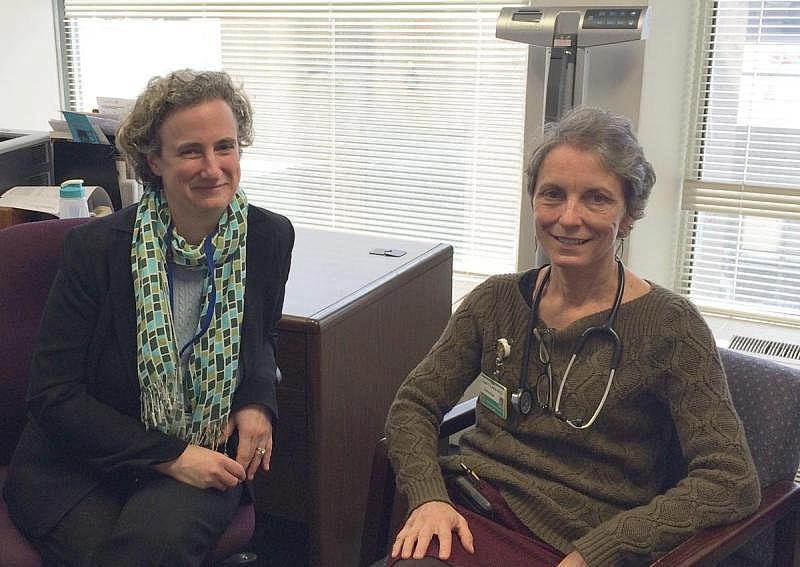

Rhode Island Hospital pediatrician Carol Lewis has made it her mission to care for foster kids. Her patients come to her with scars visible and invisible – from the stress of growing up in poverty, witnessing violence, living with addicted parents. Most have been neglected, and some have been abused. Lewis calls it chronic stress. And she says it’s like living with a wild animal.

“If you were being chased by a tiger, your heart would beat fast, you’d be ready to pop. That system, your adrenaline, that part of your nervous system gets turned on. And when that kind of trauma happens over and over again, the tiger is in the living room.”

The results? Higher rates of asthma, obesity, diabetes, to name a few.

“So these kids, often less than five, will present will sleep issues, horrible sleep problems," says Lewis. "They have bowel issues.”

Being placed in foster care adds another layer of stress. Lewis says kids might find themselves in a new town, a new school. They may have to see a new doctor or therapist. It’s especially tough for younger children, who can’t always articulate what’s wrong.

“All of a sudden there’s someone here who’s supposed to take care of you, not knowing any of your medical problems, and not even knowing who to contact to start getting that information," Lewis says. "You can imagine you probably wouldn’t feel like you were getting very good health care. And unfortunately all too often that’s what’s going on with our kids in foster care.”

So Lewis opened a clinic called “Fostering Health” at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence. The idea is to give foster kids a medical home that stays put, no matter where they move. Her staff can track down missing medical records. And the doctors specialize in treating kids who’ve experienced trauma or chronic stress.

“We think that exposure to extreme or chronic stress really sets children up," says Dr. Audrey Tyrka, a neuroscientist at Butler Hospital in Providence who studies how stress affects developing brains, "to develop not only a variety of psychiatric and social problems, but cognitive problems and medical problems.”

To find out why, Tyrka looked for the moment the damage might be taking place. Working with Rhode Island’s Department of Children, Youth, and Families, she recruited 240 kids between the ages of three and five, all of them living in poverty. About half had been involved with DCYF at some point because of maltreatment. Interviewers got to know the kids and their home environment. They peered inside their DNA, swabbing for saliva samples to measure the concentration of a stress hormone called cortisol. Tyrka says they found consistently high levels. Lots of cortisol isn’t always a bad thing. It’s lots of it for a long time.

“You need that because you need to be able to run away from a stressor or think through a difficult problem," says Tyrka. "But if that system is turned on for too long, it can have a whole host of effects because this system regulates inflammation, and brain development, and bone development.”

Tyrka and her team also found that the gene that regulates the cortisol system had often been switched off, thrown permanently out of whack. That leaves the brain unable to regulate cortisol in the body. And that’s what may be putting these children at risk for lifelong health problems – like diabetes and obesity. It also puts them at higher risk for mental health problems. And those can be tougher to address. Just getting an appointment can be difficult for kids because there’s a shortage of providers. Child psychiatrist Elizabeth Lowenhaupt says it’s even tougher for foster kids, who may not have a regular doctor.

“The reality is that it is difficult for someone to call and get an appointment within 72 hours with any provider," Lowenhaupt says. "Often times the insurance piece isn’t in place yet. So my understanding is that all kids in DCYF have coverage and that starts the day they’re removed. But they don’t have their card, they don’t have their number, it hasn’t been activated right away.”

To make matters worse, most child psychiatrists in the area don’t even take insurance. So Lowenhaupt has launched a mental health clinic for foster children.

“Our target is to have 15 patients over the course of this first year between the ages of 12 and 17 who have depression and/or anxiety, who live in foster care.”

Lowenhaupt will try a kind of intensive outpatient therapy for six months, and then reevaluate. There’s not a lot of data out there, she says, on what does work with foster children. So Lowenhaupt says this is an experiment. She believes just getting kids in for an appointment will be an improvement. If her program works, she hopes to begin treating more kids from DCYF. Her colleague, pediatrician Carol Lewis, says there’s no time to lose. Children who experience early trauma will be dealing with its impacts all their lives.

“They don’t just go away," Lewis says. "Those issues can be with them for a long time.”

Back at Butler Hospital, neuroscientist Audrey Tyrka says the prognosis for kids who have experienced abuse or neglect can look bleak. But she thinks the genetic changes she’s discovered might not be the end of the story. She says a connection with a loving adult can buffer the impacts. Plus, the body itself may be able to adapt to genetic changes.

“It’s probably the case that some genes are more plastic or able to be adapted than others" Tyrka says, "and we think these stress hormone genes are likely to be candidates for that.”

Tyrka’s research suggests getting children in the welfare system the mental and physical health support they need as early as possible is the key. That could counter the stress kids have already experienced in their young lives. But the state’s child welfare agency has been overwhelmed by an influx of cases, and resources are stretched thin.

This story was originally broadcast by Rhode Island Public Radio.