SF’s Big Street Count Is Coming Back, But Homelessness Fixes Require Deeper Reform

Kristi Coale reported this story as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Journalism fellow.

Her other stories include:

A homeless family in SF lives in housing limbo, while more city-funded apartments sit empty

SF’s Homelessness Department Has a Billion Dollars, and Brings Up Almost as Many Questions

For SF’s Homeless, A Permanent Home Is the Ultimate Goal. The Fight Is How to Get There

Building Homes for SF’s Homeless Is Hard. Providing Mental Health Care Is Even Harder

Along the Embarcadero, January 2022.

The Frisc

Five years ago, with thousands of people living on its streets, San Francisco unveiled a way to assign the neediest homeless people top priority for a relatively small amount of housing. It was a system meant to deal with a gross imbalance of supply and demand.

Last year, however, there was agreement all around that the priority system, called coordinated entry, wasn’t working. Several nonprofits that work with the homeless said it was not adequately housing people of color and LBGTQ communities, who make up a small percentage of SF’s overall population yet a much larger percentage among the homeless.

Shireen McSpadden, executive director of the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, agreed. At a public hearing in July, McSpadden said coordinated entry needed an overhaul. “Most important for us is digging into coordinated entry, along with providers and people with lived experience, to understand how we fix our system so it meets the needs of our communities — that’s my commitment,” she said.

Seven months after McSpadden’s pledge, we still don’t know when the big fix is coming. What’s more, promises to share more of the current coordinated entry data, which would be useful despite its flaws, have been slow to materialize.

This limbo comes even though the department, HSH, has more money than ever — more than $1 billion to get people off the streets and keep them housed in settings that also provide healthcare and other services. McSpadden acknowledged the benefits of this bounty: “We don’t have to work from a scarcity model like we’ve had to do in the past.”

Counting backwards

Knowing more about the homeless population in order to help them is top of mind right now. Frustration with the Tenderloin’s desperate streets, which include open-air drug dealing, has led to a 90-day emergency plan there.

And barring a delay, the city on Feb. 23 will conduct its biannual point-in-time count of people living on the streets and in vehicles. The previous count, which tallied 8,035 people, was in 2019 — the 2021 count was canceled by COVID — and an update is long awaited.

It’s also far from perfect — a 24-hour snapshot of the city’s streets, bolstered by follow-up interviews to fill out demographic details. (It’s done this way because that’s what’s required to get federal homelessness funding.)

But it’s all we’ve got, and SF lawmakers use the point-in-time data to decide how to meet new needs that crop up. For instance, when the 2019 count showed more people living in vehicles, city officials created a temporary secure site for people in their cars. Its success encouraged a longer-term site at Candlestick Point and, if promises are to be believed, another one on the city’s west side.

That’s why a coordinated entry overhaul is important. If done right, it could replace the point-in-time count with a more frequently updated picture of the city’s unhoused: where they are, who they are, what kind of help they need, and more. To convince voters and taxpayers to keep spending, however, the city must show the money is making a difference. And that’s hard to do without good data.

“When will our system move away from relying on the point-in-time count to the coordinated entry system and other ways to get a more accurate understanding of the scope of the problem? Where is the city on this?” That was Andrea Evans, grilling McSpadden and other department officials last July at a meeting of the Local Homelessness Coordinating Board, the city’s only semblance of regular oversight for HSH.

Evans’ frustration stems from her day job at Tipping Point Community, which has been funding the Chronic Homelessness Initiative for the department for five years.

In theory, the coordinated entry system could give SF a dynamic data set. Coordinated entry was created to track people coming off the street to request housing and services. To gather information, an interviewer runs through a series of questions. (Service providers have criticized the interview as too intrusive and traumatic — and in the end sometimes inaccurate, with high-priority people falling through the cracks — which has been part of the push to overhaul the system.)

Proponents of an overhaul dream of a bigger picture, not just numbers of people getting into housing, or bus tickets out of town, or short-term rental subsidies. “I see a lot of data showing outputs, but they don’t tell you how they’ve reduced homelessness,” said Mark Nagel, cofounder of RescueSF.

Nagel would like to marry the “output” data with more frequent street counts by district. Some neighborhood groups and city workers have done tent counts. Could it be expanded to count individuals? “If we don’t have frequent measurements, then we’re spending way too much money without knowing whether something is working or not,” he said.

Not really sharing

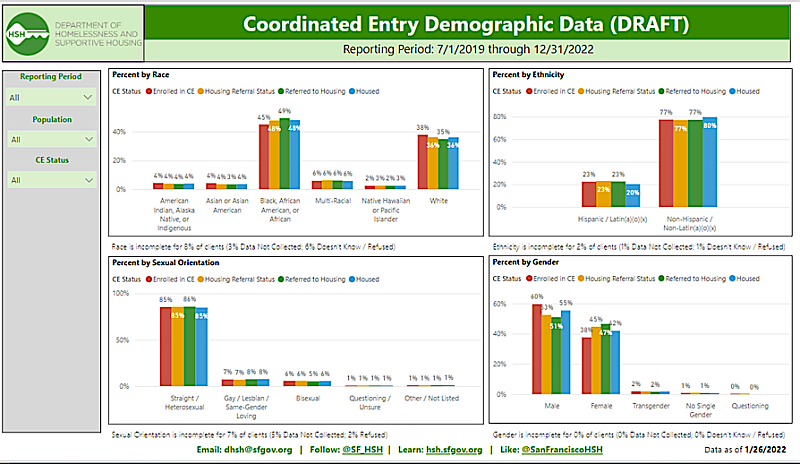

Last summer, McSpadden seemed to be getting the message for more and better data. She presented some coordinated entry data for the first time showing who was getting housing, broken out by race, ethnicity, and gender and sexual orientation.

For instance, Black people make up 44 percent of those in the system, but only 18 percent of the people who qualify for permanent supportive housing. (SF overall is 5 percent Black.) Previously, the agency would only show how many families, single adults, and youth were in the system.

“We need to see who is moving into housing,” she said. “Those are the numbers we hold ourselves to.” With Black and brown people overrepresented in SF’s homeless population, she said, “we have to make sure we are moving them into housing at the rate we should be.”

But the share was still on the agency’s terms. Big pieces remain missing. The Frisc has made multiple requests over many months for underlying coordinated entry data, but officials instead have provided slides that have already been used in public presentations.

Two weeks ago, the department said it would soon post a dashboard of coordinated entry data from 2019 to the present. They teased a preview, but the dashboard has yet to emerge. (Officials said Tuesday it could debut in March.)

SFs Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing provided this slide as a preview of a dashboard that will allow deeper dives into housing data going back to 2019. (The agency has not responded to The Friscs requests to discuss the data.)

Whenever it appears, it will be truncated. Coordinated entry started in 2017, but officials say they didn’t collect comprehensive data until 2019 because the federal government didn’t require it.

Three years ago, before COVID hit, The Frisc wrote that the early days of coordinated entry were beset with problems, such as a shortage of actual entry points where people could come in for an interview. Some of the problems have been addressed. (Pregnant women are now referred to family housing, not single adult shelters, for example.)

The city’s cash, with help from state and federal funds, is also chipping away at the shortage of housing for the formerly homeless, converting hotels and motels despite neighborhood protests. There’s money for other programs too, like the $100 million pledged by Tipping Point Community to address chronic homelessness, a particularly desperate subset of the population.

But without evidence of what works and what doesn’t, service providers — not to mention taxpayers and officials — will remain frustrated. As Tipping Point’s Andrea Feiss notes, a lot of that insight needs to come from HSH, but “they’ve had a problem of being scared of sharing.”

Staff writer Kristi Coale (@unazurda) writes about homelessness and more for The Frisc. She reported this story as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Journalism fellow.

[This story was originally published by The Frisc.]