Children In Crisis: Struggling to recruit enough foster families

Kristin Gourlay covers health care for Rhode Island Public Radio, Rhode Island's NPR station. Her series “Children in Crisis” examines the problems at Rhode Island's child welfare agency, attempts to fix them, and the impacts on children, families, and caseworkers. From the difficulties of providing quality health care to foster children to the lack of foster families willing to take in teenagers, Gourlay finds a system – and the children it’s charged with protecting – in crisis.

Other stories in the series include:

In the Colantuono's kitchen with two of Maya's biological children, Sophie (first from left) and Tori (right, holding her son), and Lana, in the pink shirt. Colantuonos fostered her as a baby but she was able to return to her mother. The Colantuonos are now her godparents, and Lana often stops by for a visit. Maya Colantuono is in the middle. Credit Kristin Gourlay / RIPR

Rhode Island doesn’t have enough foster families to meet a growing need. That’s one reason the Department of Children, Youth, and Families places a higher percentage of kids in group homes than almost any other state. DCYF officials acknowledge the problem. But recruiting new foster families has been tough.

Maya Colantuono grew up an only child. She always knew she wanted a bustling home of her own.

“I used to read books all the time about foster families and adoptive families," says Colantuono. "I used to talk to my parents all the time about adopting siblings for me."

Now, sitting on a deep, comfy sofa in her cheerful living room, Colantuono explains how she got that bustling home. She and her husband settled in a roomy yellow house in suburban Warwick , her husband in law school and Colantuono working full time. They had four children of their own, but as they grew older and more independent, a couple of bedrooms opened up. Colantuono convinced her husband they could—and should—do more.

“Let’s…you know what? We’re doing this kid thing anyway, we have the room, there are kids in need. Let’s help some kids out.”

The Colantuonos took the 10-week class every foster family needs to be licensed. DCYF agents visited their home to make sure it was safe, and to determine what kind of child might fit best. And then--

“Our license came in the mail on Tuesday. And the phone rang from DCYF on Wednesday.”

The next day, baby Lana arrived in the arms of a DCYF worker.

“She was the sweetest little thing. She only weighed less than a pound and a half at birth," Colantuono recalls. "She’d been very premature. Her mom had been using drugs. Her mom was in drug treatment.”

The Colantuonos helped Lana grow into a healthy little girl. DCYF arranged visits with her birth mother, and paid for childcare so the Colantuonos could keep working.

“It took about a year, but mom got clean, got her life together. Through the process, we all fell head over heels in love with this baby," Colantuono says.

And that was Colantuono’s first lesson in the heartbreak of fostering. Giving Lana back to her mother devastated the family. But in time, the grief subsided, and Colantuono wanted to foster again. DCYF called about a 10-month old girl whose parents couldn’t take care of her.

“The car seat is still here, the high chair, the crib is set to the right height. I thought she could just kind of plunk right in.”

But Colantuono soon realized baby Niveyah wasn’t just going to plunk right in.

“I thought, oh my goodness, what’s going on with this 10-month-old child? She didn’t wrap her legs around me, she was stiff as a board, and her little hands were balled up in fists.”

The Colantuonos took Niveyah to lots of doctors, who finally diagnosed her with cerebral palsy. The state has helped with Niveyah’s care - physical therapists, a special wheelchair. The family adapted, and eventually adopted Niveyah. Colantuono says Niveyah taught her another lesson about fostering: expect the unexpected.

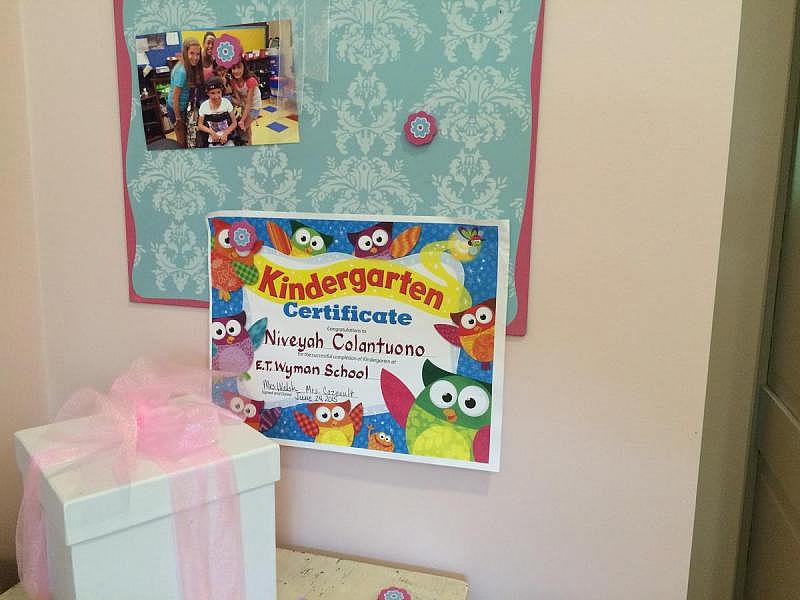

The Colantuono's adopted daughter, Niveyah, just graduated from Kindergarten. Credit Kristin Gourlay / RIPR

Since then, the Colantuonos have fostered 10 children, some for weeks, some for much longer. A picture of each child hangs in the stairway.

Hundreds more children could be in foster families now, if there were more to go around. Most of them are older, living instead in group homes.

“We’re experiencing crisis in finding foster homes for young people eight, nine, 10, 13, 14," says Lisa Guillette, who runs a nonprofit called Foster Forward. One of the organization’s goals is to help DCYF find more foster families.

In her office just across the river from downtown Providence, Guillette says she’s heard all the reasons people think they can’t foster.

“That they have children of their own, that they don’t have time, they don’t know how you do that, I could never do that, I would never be able to give the kids back…”

Ask someone if they’re interested in fostering, she says, and you hear a lot of ‘no thanks.’ It’s easier, she says, to ask people to mentor a foster child first. To volunteer an hour a week. To ask more means asking a family to foster a child who may have experienced some trauma, whether from neglect or abuse. And that can be challenging for any family, especially without the right support.

“We don’t fully understand and appreciate and invest in what it takes for a family to care for a child who’s experienced so much trauma.”

Guillette understands it’s daunting, the idea of taking in a child who might have troubling behaviors. But she says there’s another reason Rhode Island has difficulty recruiting foster families: until now the state had no coordinated campaign to find families who might be able to help. That takes a little money, and DCYF’s money has been flowing into group homes, instead.

“Our investments are not where our values are. And we’re all working together to try to flip that. We’re heavily invested in congregate care, residential care, out-of-state care. And everybody agrees that’s not where we want to be spending our money.”

Kevin Savage oversees foster family recruiting for the Department of Children, Youth and Families. He acknowledges what DCYF has done in the past hasn’t worked as well as it should, but he says the agency wants to do better. A new federal grant will help them mine data on foster families to learn what has worked, and where. He hopes to recruit more families from the communities where foster kids already live.

DCYF's Kevin Savage hopes a more strategic approach to recruiting might bring in more foster families. Credit Kristin Gourlay / RIPR

“So, in their school systems, in their communities. Close to people they know. So that’s kind of the barrier we want to break through.”

Savage knows the consequences of failing in this effort. Rhode Island already has one of the highest rates in the country for placing kids in group homes, and studies show that puts them at higher risk for problems later in life. Foster Forward’s Lisa Guillette wishes more families knew how much they were needed.

“I think Rhode Islanders care very deeply about their community. And if they had a greater level of awareness about the need, then that might inspire them to step forward.”

At home in Warwick, foster parent Maya Colantuono says fostering isn’t always easy. But she believes it’s an investment in a better future for a child.

“I believe that every child with consistency and sticking with it and knowing that these people are not going to give up on me can grow and develop. Is love enough? No. You can’t just love away their pain, or love away their trauma or hurt. But certainly love and consistency, coupled with good clinical supports and resources can make a huge difference for kids.”

Colantuono now helps other families make a difference for kids. She conducts home studies for families that want to get licensed to foster. And she shares her experience in support groups. She says it helps to remember that foster families aren’t immune to the forces that lead other families to become involved in the child welfare system – addiction, mental illness, poverty. Those families are just up against incredible odds. She thinks fostering gives them the breathing room to try to beat those odds.

This story was originally broadcast by Rhode Island Public Radio.