Chinese Immigrant Marriages - Fragility and Reality Behind a Low Divorce Rate

Photo: Jean Chung/Getty Images

Chinese culture emphasizes the importance of "family." The Chinese adage "成家立业" — build a family before establishing a career — underscores the significance of marriage as the foundation of the family. For Chinese immigrants who embark on a new life in a foreign land, marital relationships become the foundation of their social network and support system in a new and unfamiliar environment.

But the mental health of Chinese immigrants can be significantly strained by marital conflict. Factors such as immigration status, loneliness, and stigma around seeking help further complicate the situation, leaving many married couples to suffer in silence.

According to a 2020 study conducted by University of Georgia that looked at data on 250 couples over two decades, couples who frequently clash are more likely to experience feelings of loneliness and poorer physical health down the line. The research also emphasizes the significance of early prevention and intervention to mitigate marital conflict, potentially preventing poor physical and emotional health later in life.

Another earlier study from 2008 found that greater marital conflict indirectly led to increases in depressive symptoms, and suggests that couples in low-quality marriages might suffer worsening physical health.

While there are very few studies looking at the Chinese community in the United States, a study of older Chinese immigrants in Chicago revealed that the quality of spousal relationships significantly impacts their mental well-being, with the severity of depressive symptoms tied to spousal criticism and questioning.

A counseling room at Chinatown Service Center’s Behavioral Health Clinic in Monterey Park.

Jian Zhao/World Journal

Marriage is complicated for Chinese immigrants

Hidden behind low divorce rates, Chinese immigrants’ marital issues have rarely received attention, and resources for marriage counseling in Chinese communities are extremely limited.

Divorce rates are not a reliable measure of marital satisfaction, particularly for Chinese immigrants. Constrained by traditional Chinese values such as "家和万事兴" (harmony in the family brings prosperity in all endeavors), divorce is not a common choice among Chinese.

Daniel Deng, a legal advocate for Chinese immigrants in the San Gabriel Valley in Southern California, said that among the domestic violence cases he has handled, only a small fraction of families would seek a divorce due to domestic violence.

"Some victims even try to help the abusers evade punishment — because once the abuser is sentenced, the family will face heavy financial burdens," Deng said.

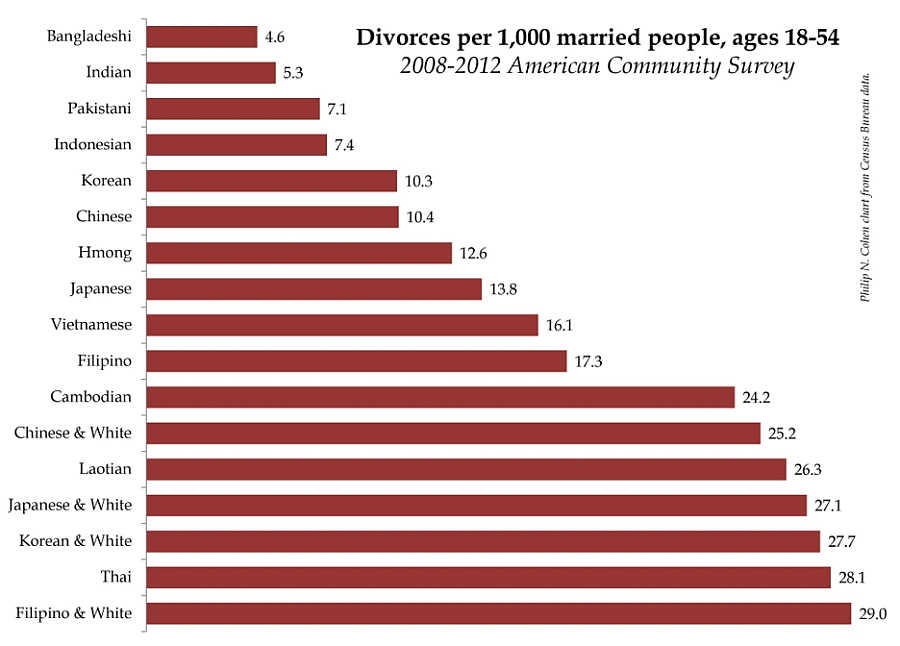

A study of 475 Chinese immigrant women, published in 2020, revealed that about 20% of Chinese immigrant women surveyed experienced intimate partner violence in the past year — a higher rate of domestic violence compared to other population groups. However, the divorce rate of Asian families has been consistently much lower than that of other ethnic groups. Even among Asians, the divorce rate for Chinese couples (10.4 per 1,000 married people) is lower than that of many Asian subgroups, including Japanese, Vietnamese, Filipino, and Cambodian couples living in the United States.

Some couples are unable to divorce due to immigration status limitations. An immigration lawyer pointed out that for immigrants who rely on their spouse's job to obtain a green card, they must remain with their spouse until obtaining the green card. The wait for a green card can take five to 10 years. Divorce would mean losing legal status to reside and work in the United States. Few immigrants are aware of special U.S. protections for crime victims, including victims of domestic violence, that could allow them to escape an abuser.

In addition, factors such as children, finances, housing, and the culture of shame around divorce are some of the reasons why Chinese couples might maintain their marital relationships despite the emotional toll.

The triple challenges of Chinese marriage

A 2010 study of immigrant families shows family conflict is a significant issue. Along with the stresses of immigration and acculturation, family members are linked in a much closer way than ever before, making family relationships more intense and vulnerable to disturbances.

And for Chinese immigrants, additional challenges can make the situation even worse.

The Chinatown Service Center provides Chinese-language couples counseling at its clinics in Los Angeles, Alhambra, and Monterey Park. However, appointments for counseling typically require a wait of at least two months due to shortage of multilingual counselors, according to Yi Zhang, a counselor working there.

Jian Zhao/World Journal

Chinese individuals encounter challenges finding a suitable partner in the US, possibly leading to compatibility issues. According to a 2023 survey by the Pew Research Center, 54% of U.S. Chinese immigrants found it very difficult to find a partner in the U.S. This proportion is higher than other ethnic groups—whites (23%), blacks (32%), and Hispanics (37%).

Influenced by the craving for companionship, some may enter a marriage in haste, laying open the possibility of marital discord later on.

Jay, a Chinese engineer based in San Jose, had been working in the United States for many years and trying to find a partner with a similar cultural background through the internet and social media.

Five years later, feeling the pressure to get married, he decided to marry a woman he was introduced to remotely by his family in China, who lived in New York, a nearly 6-hour flight away from Jay.

After they married, issues began to surface. Jay found that he and his wife often disagreed. Arguments became more frequent, and finally, two years ago, they decided to divorce.

"At first, I felt relieved, but soon, the familiar feeling returned, and there was no one to talk to except at work. To be honest, at that time, I thought even if there was someone at home to argue with, it would be better than talking to myself. With that in mind, many things I couldn't bear before seemed tolerable again, although I didn't know how long I could bear it — 10 years, 20 years, or maybe a lifetime." Jay eventually withdrew his divorce application.

A study with 3,157 elderly Chinese individuals in Chicago found that participants with more friends were less likely to report troubled marriages. This suggests that when social ties are confined to spouses, conflicts can arise.

Further, smaller social networks also mean fewer avenues for relieving stress, which can make it difficult to seek comfort and help from others.

According to Yi Zhang, a counselor working at the nonprofit organization Chinatown Service Center’s Behavioral Health Clinic in Monterey Park, immigrants are in long-term survival mode, and their mental stress is under high pressure. Some Chinese immigrant women feel sacrificed in marriage due to high demands of life and work. She added that some Chinese immigrants find it difficult to make friends due to linguistic and cultural barriers. “After arguing with their partners, there is no one to talk to,” she said. “If they were in China, they could seek help and comfort from family and friends."

Yi Zhang sitting in her therapy room in Monterey Park.

Jian Zhao/World Journal

Speaking from a clinical perspective, Daming Mu, a marital relationship counselor in Northern California, observed that a number of Chinese immigrants in the United States do not prioritize emotional communication. Good communication is critical to maintaining a healthy relationship in marriage, she added.

Frank Hu, a Chinese software engineer working in Silicon Valley, said that although many companies offer free counseling for their employees, Chinese often lack a sense of security in sharing their life difficulties and psychological conditions, or simply do not feel that their issues are serious enough to seek mental help. Also, it is also difficult to establish a connection with counselors from different cultural backgrounds.

"Seeing couples counseling as a scam"

Every family experiences conflict from time to time, but many Chinese immigrants have their own approaches in how they handle these conflicts. Due to a lack of awareness and trust of psychological counseling, Chinese immigrants rarely seek marriage counseling, and many view counseling as only for “crazy people.”

Daming Mu added, only when a marriage is on the brink of divorce, do Chinese begin to seek solutions. Furthermore, "Many Chinese see marriage counseling as a scam… Others give up quickly after trying two or three counseling sessions and not seeing immediate results on their relationships."

"Some Chinese immigrants see psychologists as a lifesaver, expecting to be told what to do," Yi Zhang added. This misunderstanding may stem from linguistic biases. In Chinese, psychologists and psychiatrists are often collectively referred to as "Mental Doctor."

"For most people, the cost of marriage counseling is difficult to bear," Yi Zhang said. Currently, the market price for commercial counselors ranges from $150 to $300; and community organizations aiming to provide public services often face severe shortages of therapists, with appointments for counseling services typically requiring a wait of at least two months, with Chinese counselors even scarcer.

"If long-standing conflicts are not resolved, it may lead to extreme situations," Yi Zhang said.

The importance of mutual compromise and gratitude

“Every marriage is different. Every marriage has an issue,” said Isaac Hung, a Chinese immigrant who has been married for 39 years and has seven grandchildren. “I haven’t seen any couples who never fight. If you are insisting on one thing, there will be fights. If you continue to fight when you get tired, that’s when couples separate.”

“To resolve conflicts, we need compromises, sometimes from you and sometimes from your partner. And most importantly, we also need to say thank you and show gratitude, acknowledging the compromises made by your partner and making them feel valued. It’s a mutual respect.” Isaac shared.

“However, in traditional Chinese culture, men often feel themselves as being stronger and better. It is hard for them to go back and say thank you or I’m sorry, including myself.” Isaac continues, “But these are the principles. That’s how we can keep the marriage and relationship stronger.”

Resources Available to Help Resolve Conflicts

While counseling for marital issues, especially in Mandarin, Cantonese or other dialects, is limited and often expensive, there are still some free resources available. According to Daming Mu, in Chinese Churches there are often family support groups where couples can seek assistance from pastors when conflicts arise. Although it is not the same as professional counseling, couples can still get emotional support and help to ease conflicts.

For Medi-Cal or Medicare members, Chinatown Service Center offers community counseling service, including marital counseling. They also provide a sliding fee scale based on income level and family size for those who do not qualify under insurance. For couples wanting to find a licensed therapist, Psychology Today is a free searching platform to offer help.

For those in need of immediate assistance locating counseling resources or seeking emotional support to address a problem, they can call 211 (nationwide) or 800-854-7771 (in Los Angeles County) to speak with a live person who can help. For issues related to domestic violence, call 800-978-3600. All these hotlines are available 24/7 and provide services in Mandarin and Cantonese upon request.

This World Journal project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong Ethnic Media Collaborative reporting venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.