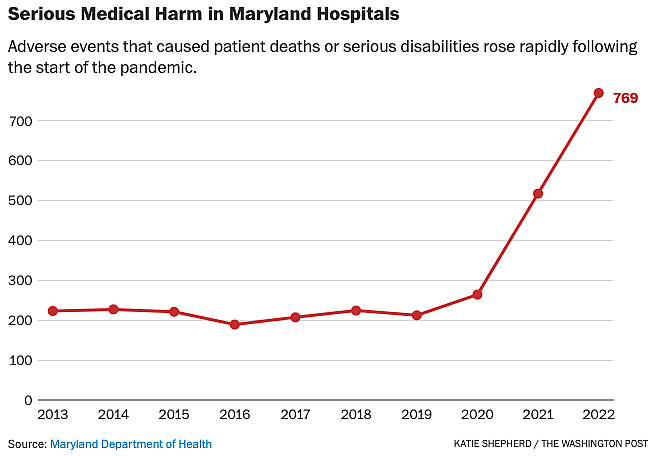

State data shows serious harm inside Maryland’s 62 hospitals more than tripled between 2019 and 2022 to 769 incidents that killed or injured patients, reaching the highest level since the state began collecting patient safety data in 2004. Safety experts say the historic rise of dangerous missteps, probably fueled by staffing shortages and the strain of the pandemic, may signal systemic failures.

Dangerous missteps more than tripled over 3 years in Maryland hospitals

This project was originally published in The Washington Post with support from our 2023 National Fellowship.

A premature baby was given four times the safe daily dose of a steroid for 13 days. A patient went in for surgery on one leg and ended up losing the other leg to compartment syndrome. Three people died after a maintenance worker inadvertently shut off an unlabeled oxygen line.

That increase in deaths and injuries was obscured from the public for months after the state agency tasked with overseeing patient safety lost access to the database it had used to track those incidents in a December 2021 cybersecurity breach, which compromised its ability to scrutinize harm as hospital safety declined across the state and nation.

KATIE SHEPHERD THE WASHINGTON POST

The state delayed releasing its latest patient safety report for nine months after The Washington Post first requested the data, which was less comprehensive than previous years’ after regulators scaled back collection practices. The state does not publicly identify the hospitals where harm occurred, citing state law and the need to encourage hospitals to report mistakes without fear of public scrutiny.

The Maryland Department of Health’s Office for Health Care Quality has collected limited information on harmful events since the ransomware attack, from which the agency is still working to recover. The department, for example, could not say how many Maryland patients died because of mistakes in hospitals during the 2022 fiscal year. That number was 86 in the 2021 fiscal year — nearly double the previous count.

“Marylanders deserve transparency and accountability,” Chase Cook, a spokesman for the health department, said in a statement responding to questions about the data. “The Maryland Department of Health is working to construct any missing information from available records.”

Anna Palmisano, a microbiologist who now runs the advocacy group Marylanders for Patient Rights, said the increase in patient safety incidents underscores how important it is to closely monitor harm inside hospitals, and said the state should be doing more to hold hospitals accountable.

“It’s totally the state’s responsibility,” she said.

Although hospitals are heavily regulated, very little information on medical harm ever becomes known to the public — in part because of valid concerns over privacy, but also because state and federal regulators do not closely track many key indicators of systemic problems, and they rely heavily on hospitals to voluntarily report their own missteps.

Experts say that approach means that for every serious event that gets flagged, there are dozens of less harmful incidents and near misses that never get documented.

“This could be, conceivably, a tip of the iceberg,” said Donald Berwick, a former administrator for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and founding CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. “They are counting real people who suffered real harm. It does suggest that something is going on.”

The spike in serious adverse incidents comes as patient safety experts are warning that hospitals across the nation could be experiencing a backslide in a decades-long effort to make hospitals safer through systemic reforms. As hospital systems emerge from the strain of the pandemic, experts say leadership must make safety a top priority to reverse the damage done over the last few years as doctors, nurses and other front-line staff suffered from staggering levels of burnout and considered leaving the medical field in unprecedented numbers.

“It’s very alarming,” said Gail Kingman, a registered nurse of more than 30 years and an administrative organizer for 1199 SEIU United Healthcare Workers East. Kingman said that the state’s rising numbers reflect the reality inside Maryland hospitals, where health-care workers have reported to the union that they are witnessing assaults, finding patients missing from their rooms and seeing many other frightening situations on a weekly and sometimes daily basis. “It’s very scary,” she said, “it truly is.”

Berwick said that ultimately, the responsibility for fixing systemic issues driving the uptick lies with hospital administrators and boards that make financial decisions for medical centers.

“The safety community at large is concerned that even pre-pandemic, and during the pandemic, a lot of hospital leaders may have taken their eye off the ball,” Berwick said. “Unless the [hospital’s] board of trustees are attending to safety as their highest priority, you will lose traction.”

The American Hospital Association declined to comment on the rise in patient safety incidents in Maryland. The Maryland Hospital Association did not have an immediate comment on the increase.

Although experts say there is no comprehensive measuring stick to compare patient safety from state to state because federal agencies don’t collect sufficient data, Maryland ranks 50th among the states for the longest emergency room wait times, a metric safety advocates call a canary in the coal mine for health-care quality. The Leapfrog Group, a private organization that evaluates hospital safety metrics, ranks Maryland 35th for patient safety — only nine Maryland hospitals received an A in safety from the group.

State Sen. Clarence K. Lam (D-Howard), who is a doctor and sits on the Senate Finance Committee that oversees health care, said that a sharp rise in hospital-associated safety incidents and deaths raises red flags, but he hopes that the numbers may have improved as the worst effects of the pandemic waned. If patient deaths and injuries continued to rise in fiscal 2023, he said, the state has a real problem to face.

“If they continue to rise at this rate, the state should take a look at how we can … help get at the root cause of the problem and prevent it,” he said.

The Office of Health Care Quality’s Patient Safety Program primarily relies on hospitals to self-report adverse events, which Maryland defines as an “unexpected occurrence related to an individual’s medical treatment and not related to the natural course of the patient’s illness or underlying disease condition.” Only incidents that kill or seriously disable a patient must be reported, but hospitals may voluntarily report less severe events. The vast majority of information collected by the state when reviewing medical harm is shielded from public disclosure, so the agency’s annual report provides the clearest view of patient safety inside Maryland hospitals. The state declined to release any of the underlying data to The Post.

In one incident, a surgeon mistakenly operated on the wrong finger because the incision site was not marked properly.

In another, emergency room staff left a woman in crisis alone; she slipped out of the hospital and jumped from a nearby bridge.

During a 10-hour surgery, the surgical team did not reposition or test blood flow to a patient’s leg that wasn’t being operated on. By the time doctors evaluated warning signs that the leg had been injured, compartment syndrome had set in and the surgeon had to amputate below the knee to save the patient’s life.

A premature baby with extremely low birth weight received four times the safe dose of a steroid because of a confusing system for ordering medication that failed to note that the daily dose should have been divided up over four courses each day. The medication error continued for 13 days, without objection from a doctor, nurse or pharmacist, before someone noticed the mistake.

The health department denied requests for records that would provide more details on the adverse events.

“It’s not uncommon for those reports to be not public so that you can focus on the outcomes or lessons learned,” Tricia Nay, the director of the health department’s Office of Health Care Quality, said in an interview.

After reporting an adverse event, hospitals are required to investigate what caused the harm and submit to the state a plan to fix any problems. The state signs off on those plans but does not make the investigations public. The state can use civil fines to discipline a hospital for especially egregious or repeated safety deficiencies, but Nay said the Office of Health Care Quality rarely does so. In most cases, she said, the state returns those fines to hospitals with the promise that the funds be spent on measures to improve patient safety.

When hackers attacked a health department server with ransomware in December 2021, the Office of Health Care Quality lost the ability to add new data to the patient safety database that tracked up to 52 data points from each adverse event reported by a hospital. In its place, the agency created a stopgap rubric to track new patient safety incidents that includes 12 fields of data.

The new spreadsheet, a copy of which the agency would not provide, abandoned many efforts to document the harm to patients, including their prognosis, and no longer includes any detailed description of the incident beyond a general “event type” and basic details about where and when the event occurred.

State regulations require hospitals to inform the patient or the patient’s family “whenever an outcome of care differs from an anticipated outcome.” The Office of Health Care Quality’s old database included a field to indicate whether the family had been notified of an adverse event, but the temporary spreadsheet does not track that information. The agency also in the past disclosed how well hospitals were complying with that requirement to inform patient families of serious mistakes, but stopped including that information in its annual reports after 2014.

Patient safety advocates say they have been pushing for more information to be made public by regulators and hospitals alike, but have made few gains. Even Maryland’s limited annual reports go further than many states, some advocates said, but they still leave many questions unanswered.

“Lack of transparency is one of those things that those of us in the patient safety community growl about a lot,” said John James, a toxicologist who became an advocate after the death of his 19-year-old son and now runs Patient Safety America.

James and other safety advocates said that relying on hospitals to self-report critical incidents and allowing them to do so without having to disclose those incidents to the public allows many adverse events to go unreported and unaddressed.

“My opinion is that hospital systems are not all that great at learning from their mistakes,” James said. “It’s sad to say, but a lot of their mistakes are still buried.”

The health department said that it is working on building a new database to more robustly track patient safety incidents, which should be ready this fall. The agency added that Gov. Wes Moore’s administration is working to identify information that was missing from that 2022 report, including the number of patient deaths, from available records and will share that data as soon as possible.