DDT’s toxic legacy threatens LA residents who fish for food

The story was originally published by LA Public Press with support from our 2024 California Health Equity Fellowship.

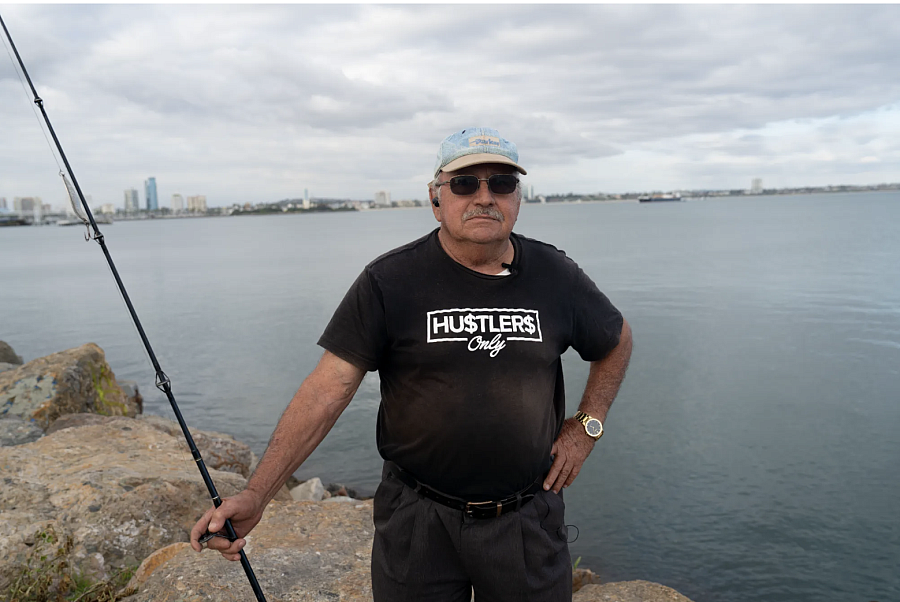

Leo at the Belmont Veterans Memorial Pier. He started fishing in his native Philippines as a young man.

(Jackson Hudgins)

On a recent afternoon at Long Beach’s Pier J, as massive container ships lumbered in the distance, Darrel Cooley relaxed in a red canvas folding chair with two fishing-lines in the water.

Like thousands of other fishermen along this 50-mile stretch of coastline from Santa Monica to Seal Beach, he was casting in what’s known as the ‘red zone’: one of the largest areas of DDT contamination in the world.

Exposure to DDT can lead to serious health problems. Cancer, liver disease, and other illnesses of the immune and endocrine systems can all be driven by DDT, according to the EPA. Some bottom-feeding fish here are so contaminated the state deems them unsafe for human consumption.

Cooley eats what he catches. “Halibut, sharks, rock cod bass, stingrays,” he said, smiling. “I like it all.”

Despite the warning signs along the waterfront, he sometimes eats fish on the list to avoid. “I haven’t been sick ever,” he said. “I haven’t heard anyone dying of it.”

In the end, he said sometimes decisions people make about what fish to keep come down to circumstances beyond their control. In a city where approximately 1 million households are food insecure, pier fishing isn’t just recreational — it’s a tool for survival.

“Some people need to fish to eat,” he said.

Darrell Cooley at Long Beach’s Pier J.

(Jackson Hudgins)

A Toxic Legacy

Between 1947 and 1971, the Montrose Chemical Corporation piped more than 1,700 tons of the synthetic insecticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane — better known as DDT — into the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Palos Verdes, California. Wastewater from a chemical facility in Torrance flowed through LA County’s sewer system to marine outfall pipes offshore, where a toxic underwater cloud settled over about 17 square miles of ocean floor. Hundreds more tons were dumped off barges into the deep ocean.

Today, more than 50-years after the federal government banned DDT from use in the United States, the pesticide’s toxicity continues to linger and concentrate into the food chain.

But many fishermen in Los Angeles County, most of them non-white immigrants also known as ‘anglers’, depend on what they catch to help feed themselves or their families, potentially putting themselves and others at risk.

“We definitely have data on fish, on the sediment, to show there’s enough contamination in those fish that could cause concerns to anglers,” John Chestnutt of the Environmental Protection Agency told LA Public Press. “Particularly subsistence anglers.”

DDT is a powerful pest killer. It’s a chalky white synthetic substance found startlingly useful as an insecticide in the late 1930s. First put to widespread use in World War II, it was hailed as a scientific miracle on par with the atomic bomb. Sprayed as an aerosol or applied as a powder, it can virtually eliminate insects that spread diseases like malaria and typhus, and was used widely around the world during the 20th century.

The compound is stubbornly resistant to environmental degradation. It’s among the infamous class of pollutants known as a ‘persistent organic pollutant’ or ‘forever chemical. Once introduced, it can persist in the environment for generations, with magnified effects higher up the food chain.

Not just insects are vulnerable. And by the 1960s, concerns about DDT’s disastrous effects on food chains that depend on insects went mainstream, largely through Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring. Many insects had also begun to develop resistance to the chemical. As evidence of its widespread ecological harm became impossible to ignore, the US EPA banned it in 1972. Today, the International Agency for Research on Cancer considers DDT a probable carcinogen.

As research uncovers new evidence of chemical dumping during the postwar era, and the EPA continues to struggle with the remediation of the nearshore DDT deposit, the work of protecting LA’s subsistence fishermen has taken on a new urgency.

“It’s kind of one of the world’s largest experiments,” said Toni Sleugh, a PhD candidate in Marine Biology at UC San Diego, who studies the region and the impacts of DDT on the environment. “We just don’t know what happens, really, with contamination on this scale over this period of time.”

The Montrose Factory in Torrance. Today the EPA operates a groundwater treatment system on the site.

(Jackson Hudgins)

The Montrose Factory

No place in America produced more DDT, or bears more of its environmental burden today, than Southern California.

In 1947, the Montrose Chemical Corporation opened its DDT factory hoping to capitalize on significant postwar demand for the product. For the next 35 years, it operated continuously on a 13-acre plot in Torrance, in Los Angeles’ South Bay.

Montrose produced high-quality DDT, and soon cornered the market. By the late 1950s, it was the largest DDT producer in the world, responsible for nearly 40% of the national supply. It also, according to David Valentine, produced about a million gallons of acid waste a year.

“At the time, the mantra was ‘dilution is the solution to pollution,’” said Valentine, a professor of earth science and biology at the University of California Santa Barbara, and a leading researcher of the environmental impacts across the Southern California coastline. “I don’t think there was any substantial thought about what it might do to the environment.”

For decades, the company legally sent its toxic effluent directly into LA County’s sewer system, where it met the ocean about a mile and a half off the coast of the Palos Verdes peninsula. Significant quantities of DDT remain partially buried on the seafloor there today. In the areas closest to the outfall pipes, contaminated sediment is as much two feet thick.

Scientists believe much of the DDT circulating in the ecosystem today likely comes from this shallow, near-shore deposit. Toxic particles accumulate in microbes or are consumed by smaller creatures, which are in turn eaten by larger ones. Bottom-feeding fish are particularly exposed.

Valentine said the ocean dumping off the coast of Southern California effectively proved the opposite of what 20th-century regulators had first expected when DDT was introduced into our natural systems.

“The prevailing thought was that DDT should degrade within a couple of years, and they had some reasons to think that,” he said. However, “we know today that if you dilute the stuff into the environment, that you will see it re-accumulate in the higher levels of the ecosystem, particularly in the predators.”

The Palos Verdes Peninsula, where the waters contain some of the largest deposits of DDT in the United States.

(Jackson Hudgins)

The Red Zone

For Southern California’s subsistence fishers, the result is a persistent and imperceptible health hazard.

“The main concern is that the chemical builds up in the body. It bio-concentrates,” Dr. Henry Anderson, an expert on environmental exposure and adjunct professor at the University of Wisconsin Madison told LA Public Press. “There’s a cancer risk. But that isn’t a risk that’s immediate. You don’t eat the fish and then the next year, you get cancer.”

Nine public fishing piers, where Angelenos can cast into the Pacific without a permit, stretch into the area’s most impacted waters. On any pier at any time, you can find hundreds of anglers trying their luck with their buckets, coolers, and tackle boxes opened with a glittering array of lures.

Pier fishermen – overwhelmingly male – are a unique demographic distinct from commercial or sport fishermen. About 60% identify as Latino, according to Heal the Bay, and 84% speak something other than English as their primary language. Many are immigrants, who live in neighborhoods that already bear some of the highest pollution burdens in California.

Crucially, four out of five pier fishermen also report they are fishing to supplement their diet.

That kind of pressure means potential risk from a pesticide dumped some 75 years ago takes a backseat to more urgent concerns.

“This can be their only protein source,” the EPA’s Chestnutt said, speaking of subsistence anglers. “And we can’t really stop people from eating it.”

Along the waterfront, nearly every fisherman says they avoid fish on the “Do Not Consume” list. Those include barred sand bass, white croaker, black croaker, topsmelt, and the pacific barracuda. But they’re often quick to tell you that others eat them.

Tony Ortiz, originally from Morelia Mexico, has been fishing in Los Angeles for 50 years.

(Jackson Hudgins)

“Most of the time I turn it back,” says Tony Ortiz, a fisherman from Morelia, Mexico who’s been fishing in Long Beach since 1974. “Usually right now it’s only Mackerel, and topsmelt. But the topsmelt is contaminated.” He points to an advisory sign in the distance. “It says it’s not for human consumption.”

Ortiz says he still sees plenty of people eating fish they probably shouldn’t be. But there’s other, more obvious, pollution he’s worried about: “Every time it’s raining, you can see chairs and couches here, and mattresses, in the ocean. A lot of trash.”

Others are skeptical that many people are really fishing to eat in Los Angeles. Jason Young fishes about three times a week, up and down the coast. “If you try to fish for your diet, to supplement your food, you’re going to be starving,” he said. “Because, first of all, there’s hardly any fish out here.”

But Young says he knows plenty of people eat contaminated fish. “Some people will take it home and eat it, more so. So they take that risk, you know. But we do tell them. I do tell them. To educate them, you know.”

In 1989, as the scope of the DDT contamination became more clear, the Montrose plant was placed on the Superfund National Priorities List, a register of the most serious hazardous waste sites in the country.

The next year, the California Attorney General and the Justice Department sued the company and other polluters. In 2000, after a decade of legal wrangling, they reached a $73 million settlement to clean up the seafloor contamination and “restore the ocean environment off the coast of Los Angeles.”

A man who declined to give his name fishes on the Belmont Pier.

(Jackson Hudgins)

How are we going to clean it up?

Cleaning the pollutant has proved, to date, nearly impossible. The EPA estimates the terrain surrounding the sewage outflow pipes retains an estimated 110 tons of DDT over about 9 million cubic meters of sediment — the equivalent of 134,000 40-foot shipping containers filled with sand, a hypothetical cargo load large enough to require six of the world’s largest container ships to carry.

The area is too large to dredge. A pilot test of the EPA’s preferred plan, a “cap” of clean sediment over the contamination, ended up resuspending some of the buried DDT, according to Chestnutt, who oversees the Montrose Superfund Site.

“When the sand fell on it, it sort of blew it up into a cloud, if you will,” he said. “And then unfortunately, in some cases, [it] settled right back down. In some cases, right on top of the cap.”

Plans are in the works to test new options, according to Chestnutt, including the placement of carbon pellets that contaminants would bind to, and technology that disperses sediment gently, in rows, through the use of long tubes.

In the meantime, more than $30 million has been spent on other environmental remediation efforts, including kelp reforestation projects and monitoring of bald eagle and peregrine falcon populations.

Others suggest that just leaving the polluted area alone might be the best option. The quantity of DDT on the shelf is slowly dropping. Some of the contaminants have been carried into deeper water, and new sediment continues to gradually build on top of the DDT-impacted layers.

“I would say right now that’s kind of one of the best options we have,” said Sleugh, of UC San Diego. “Which is, I mean, yeah. It’s kind of sad. It’s like not — it doesn’t feel like we’re doing a lot.”

Education and Outreach

In the absence of a practicable cleanup option, the EPA has opted to focus its resources on outreach and prevention. For two decades, a program called the Fish Contamination and Education Collaborative has been conducting outreach with communities, fishermen, and businesses, using money from the Montrose settlement.

The centerpiece of that effort is the Angler Outreach Program, a team tasked with the day-to-day work of reaching and informing pier fishermen of the dangers of DDT contamination.

Every week, members of the team make the rounds across eight piers, conducting surveys, handing out pamphlets, and engaging community members in conversations in multiple languages.

Angler Outreach Program employee Crystal Barajas with her clipboard on the Santa Monica Pier.

(Jackson Hudgins)

“The mission is to really reach subsistence anglers that are coming out here to get their main source of protein out on the piers,” said Crystal Barajas, an Angler Outreach Program team member. “There’s a lot of really negative health effects when you’re consuming those contaminants.”

Barajas spends her days talking with fishermen. On springtime Saturday, she started at the Santa Monica Pier, passing out information to anyone with a pole in their hand.

Moses Zuniga, a relatively new fisherman, took a pamphlet, but said was well aware of contamination issues. “Get rid of them, you know, just toss them out,” he said, of contaminated fish. “They’re pretty badly contaminated, especially in Marina Del Rey. That’s where I fished most. And there, they’re pretty bad.”

Some were learning about the contamination for the first time. Others waved her off completely.

“There’s definitely still gaps,” Barajas said. There are language barriers and, inevitably, the team can’t reach everyone. “We come here at ten, we’re missing a whole mess of people that are probably here in the early morning… we do outreach Saturdays in the evenings, but that’s just Saturdays.”

Frankie Oralla has been the program manager of the Angler Outreach Program – managed Heal the Bay – for 20 years. He’s seen demographics change at different piers, watched new immigrants arrive, and new generations come of age.

“I met many years ago people that were coming here for the first time. And [now] I’m seeing the kids of these anglers,” he said. “And we still have the problem.”

Kevin Amaya fishes with his family on the Redondo Beach Pier. His father and uncle, both from El Salvador, fish nearly every weekend.

(Jackson Hudgins)

Outreach teams work not just to advise fishermen to abstain from eating contaminated fish, but also provide information about how to minimize exposure if they do choose to consume them.

Oralla says some rely on inaccurate information about the contamination — like the idea that boiling a fish will remove the chemicals. (In fact, eating the whole fish, rather than just the filet, can significantly increase one’s exposure to DDT.) Others see clean beaches and deep blue water, and find it hard to believe there’s any danger.

“Most of the locals are subsistence anglers spending a lot of time on the pier, trying to make sure they’re bringing food and fish for families,” Oralla said. “We want to make sure that anglers are aware of local fish contamination, so they can bring healthy food.”

DDT’s effect in humans

The science is clear: DDT is toxic for humans. Studies reliably show a relationship between DDT exposure and adverse health reactions, including breast cancer, diabetes, and decreased semen quality. The impacts can last generations — one recent study shows the granddaughters of women exposed to DDT while pregnant may still suffer health impacts.

“With respect to cancer as an outcome,” Dr. Michelle La Merrill, an environmental toxicologist at UC Davis, said, “the assumption is that there’s no threshold. So every molecule creates some level of increased risk.”

La Merrill stressed the risk was measured over the course of a lifetime, and that eating fish within guidelines was safe.

Dr. Anderson, of the University of Wisconsin, agreed: “The greatest risk is reproductive outcomes. So the main thing would be the women of childbearing age are the ones that really shouldn’t be eating them. Or kids.”

Other research documents health impacts on marine mammals in Southern California. About a quarter of sea lions here have a rare urogenital cancer linked to DDT. Local bottlenose dolphins have 45 DDT-related compounds in their blubber, along with higher overall DDT exposure levels than anywhere on earth.

Despite years of sustained effort, and the large number of fishermen outreach members have interacted with, it can still be difficult to change behavior.

A 2014 seafood consumption study, the most recent large-scale study available, found 61% of anglers surveyed reported awareness of the advisory warnings, but only 42% of those aware reported changing their behavior because of those warnings.

Signs warning of contaminated fish are unavoidable at piers across Los Angeles.

(Jackson Hudgins)

In other words, just a quarter of fishermen on the piers changed their habits.

“Even the people who know the information, I’ll still see them take a croaker, or a barred sand bass,” Barajas said. “Mostly croaker, which is the worst one, unfortunately.”

Outreach data from October 2022 to September 2023 shows the AOP contacted about 11,000 anglers over 12 months. 72% were already aware of contamination. But that still means thousands of people fishing on the pier, of the subset of fishermen who were willing to talk with outreach workers, were unaware of the danger.

A significant gap in reaching the most vulnerable fishermen is the language barrier. Signs at every pier highlight dangerous fish, and feature a variety of languages, as do the tip cards the AOP hands out. But the sheer diversity of fishermen on the pier makes it difficult to reach everyone in their native tongue. The program currently employs Spanish, English, and Mandarin speakers, though they’ve conducted outreach in other languages in the past.

Oralla, the program director, emphasizes the program’s success. They’ve reached nearly 200,000 people over the course of the last two decades. Plus their signage — which survey data shows is the main way anglers find out about pollution — is ubiquitous and clear, spreading the word even when team members aren’t physically there.

But he knows there are still anglers unaware of local fish contamination. He said it’s crucial to reach as many people as possible, especially people who don’t speak English. While some residents are aware, many subsistence fishers have no idea what lurks in the water. “They’re not aware of our local fish contamination,” he said. “They don’t know what DDT is, they don’t know what PCBs are. They don’t know what happened here.”

A 2020 Los Angeles Times report brought renewed public and political attention to this pollution, and a worrying drumbeat of discoveries has followed.

In February, David Valentine and a team of researchers, using underwater remotely operated vehicles, discovered a massive deposit of DDT that stretches 15 miles along the bottoms of the San Pedro Basin, in between LA and Catalina. Now the task is to see how far it extends North and South.

“Now we have technology that can get us to the point where we can start — start — to get a sense of understanding what is in the deep ocean,” Chestnutt said. “The collective scientific and government organizations are in the infant stages of trying to understand this issue.”

Just how much is out there will be a crucial question, but certainly not the only one. Teams of researchers are hard at work trying to crack many others.

But amidst a sea of open questions, one thing is certain: The DDT off the coast of Southern California is not going away anytime soon.