Disabled teen rages, pounds on cell door and confounds Florida juvenile justice

This article and others to come are produced as part of a project for the National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Read more here: http://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/broward/article133920384.html#storylink=cpy

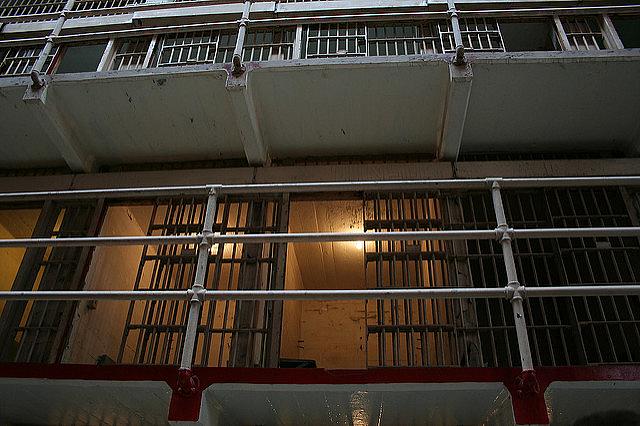

Inside his cell at the Broward County juvenile jail, Keishan Ross squalls.

They are deep, primal, piercing screams, and they are unrelenting. And he pounds on a door. His voice and his fists can be heard from far away, through his cell’s steel door, across a sparsely furnished day room, through another steel door and into a hallway where the state’s juvenile justice chief is speaking with two reporters.

Christy Daly is stricken. She rests her hand at the base of her throat.

He shouldn’t even be here, she allows.

At least 13 times in the past six years, psychologists and psychiatrists have declared Keishan Ross too intellectually disabled or mentally ill to be judged for the one-child wrecking crew he has become. His intelligence score has been tested at between 51 and 61, well below the threshold of intellectual impairment. He’s 17 now, and reads at the level of a first- or second-grader. Some days he can spell his name, or remember what to call his lawyer. Some days he can’t.

The doctors have consistently said that Keishan should not be incarcerated, but housed in a secure residential facility, where he can be given medication, therapy and intensive behavior management both for his own safety and that of anyone with whom he comes in contact.

But beds at residential facilities for children like Keishan can cost more than $130,000 each year, the state says. And Florida doesn’t have nearly enough of them.

So Keishan is returned to the lockup, again and again and again and again.

And he rages there.

“He rages because of his frustrations, his frustration of not understanding where he is, and the legal limbo he finds himself in,” said Gordon Weekes, who heads the Juvenile Court division for the Broward Public Defender’s Office, which represents the teen. “The system is just so mired in mud, and it won’t look at the child and say ‘we’ve got to do something.’”

Juvenile lockups and correctional programs long ago became warehouses for children with developmental disabilities and mental illness, just as prisons are home to thousands of disabled adults. The “maladaptive behavior” that is a key symptom of mental retardation also can lead to delinquency at an early age.

Daniel Armstrong, director of the University of Miami’s Mailman Center for Child Development, said there is broad consensus that at least 65 percent of the youths in state juvenile justice programs are developmentally disabled. Some of them are capable of understanding the legal system, but many never will be.

He rages because of his frustrations, his frustration of not understanding where he is, and the legal limbo he finds himself in. Gordon Weekes, head of the Juvenile Court division, Broward Public Defender’s Office.

“The sad part of the story, and it happens way too frequently, is that because of their disruptive behavior, they cross into the juvenile justice arena,” Armstrong said.

Keishan’s mother, Katrina Ross, 37, said it’s difficult on her family when her bewildered son is ping-ponging between the detention center and a youth camp in North Florida that is supposed to make him competent to stand trial. “It’s hard sometimes to sleep, or eat, not knowing if he’s here or there,” Ross said. “It’s very frustrating. Very.”

Florida has set aside almost 350 beds statewide for delinquent youths with cognitive impairments or severe mental illness, among 2,078 total beds. And there are other youth receiving mental health services elsewhere, said Heather DiGiacomo, a Department of Juvenile Justice spokeswoman.

As for Keishan, or children like him, “there really aren’t any significantly good programs in the area, or even in the state,” Armstrong said.

Daly, as well as a spokeswoman for the state’s disabilities agency, declined to discuss Keishan directly. They both said they expect their respective agencies to meet soon to find a way to help the teen, and are committed to aiding other children like him.

Square one

On Feb. 8, Broward Juvenile Judge Michael Orlando ordered that Keishan be sent to a Fort Lauderdale psychiatric hospital for a battery of tests to better determine his intellectual capacity and mental health. At the last minute, though, the hospital refused to accept him. Keishan’s lawyers told the judge a DJJ probation officer had disparaged the youth to hospital staff, and told them another facility didn’t want him. “The youth has serious anger issues as displayed in his last few charges, wherein he attacked detention staff,” the probation officer wrote in an internal email. “The youth has no regard for his victims.”

Keishan’s last two arrests were made only in the past few weeks. He was returned to the detention center around Jan. 29, a few days after the Apalachicola Forest Youth Camp refused to accept him. He’s been accused of assaulting a guard, and, later, another youth, since he returned.

At a hearing Friday, Keishan’s lawyer, Christine Glennen, pronounced herself “livid” over the email, and questioned why DJJ would sabotage one of the youth’s last chances before adulthood for meaningful help. “I’m furious, furious after all this hard work,” Glennen told the judge. “We’re back to square one, trying to get Keishan out of the detention center.”

Square one is a familiar place for Keishan Ross.

He was 3 when his teachers first suggested testing: “The evaluation revealed Keishan’s overall intellectual functioning fell within the low range.” When Keishan was 5, a Broward schools psychologist wrote that he “demonstrated very deficient intellectual skills.” A school evaluation from October and November 2010, when Keishan was 10, reported his intelligence scores ranging from 51 to 61, “associated with a diagnosis of mental retardation,” a later report said.

Keishan also has been diagnosed with severe ADHD, “intermittent explosive disorder,” conduct disorder and bipolar disorder.

Aside from his low IQ, Keishan has been diagnosed with severe ADHD, ‘intermittent explosive disorder,’ conduct disorder and bipolar disorder.

Janet I. Warren, a professor of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences at the University of Virginia who specializes in competency issues, said that, if the tests measuring Keishan’s IQ at the 55 range are authentic, his level of intellectual impairment means he could never be competent to stand trial, and “should be moved out of the justice system” altogether.

Keishan’s lawyers have argued that before, but with no success.

When Keishan was 12, a Weston psychologist was asked by the state Agency for Persons with Disabilities to determine whether Keishan was “mentally retarded or autistic, and, if so, competent to continue with proceedings.” The report by Bet Freeman concluded Keishan’s full-scale IQ was 55. But, she added, her results were “not deemed to be a valid indicator of his intellectual functioning because of Keishan’s inattentiveness, refusal to cooperate and obvious lack of focus, effort and test-taking behaviors.”

Keishan, she believed, was much smarter than he was letting on. The scores, she wrote, “are believed to be an extreme underestimate of his actual cognitive abilities.”

The report made it impossible for Keishan to get services, his lawyers say. He’s been in a revolving door ever since.

Keishan’s first lawyer at the Broward Public Defender’s Office was Harriet D. Gustafson. Because Keishan couldn’t remember how to say “Miss Harriet,” she told him to think of what’s on top of his head. Now he calls her “Miss Hairy.”

How many robberies does someone have to commit before you say this program is not going to work? Assistant State Attorney Kenneth Cohen

The first time she met him, Gustafson handed him a plastic-wrapped peppermint candy from atop the court clerk’s desk, and said he could have another if he behaved well through his court hearing. He did, and Gustafson learned her first lesson in understanding Keishan: He responded very well to praise or positive reinforcement. Anger or punishment? Not so much.

It is the cornerstone of behavior management for disabled children. But detention centers aren’t built that way. If the guard on shift understands Keishan — and comes prepared with honey buns or candy — Keishan might have a good day, Gustafson said. If the officer is impatient, Keishan is at risk of picking up new charges.

‘You got $1?’

Keishan was 11 when he was first arrested. Eventually, local police knew him by name. In June 2011, he demanded money from two brothers who were walking home from school. In October 2011, he broke into two cars outside a church and ransacked them. In February 2012, he demanded money from a woman outside a Walgreens. “You got $1?” he said. That same month, he threw a rock at the car window of a 72-year-old woman, and blocked her path. “Shut up or I’ll kick your ass!” he screamed.

The following August, Keishan could scarcely sit still long enough for a psychologist to evaluate him. He kept jumping up and wandering down the hallway, “randomly ringing doorbells.” He was ordered into a community mental health program.

On May 11, 2012, he demanded a dollar from a woman outside a CVS. When the woman turned her back on him, he yanked a gold chain off her neck. The mugging was traumatic, the woman later testified: “I just got so nervous. I’m afraid to even go in that shopping center now.”

At a hearing before Orlando on May 30, 2012, Assistant State Attorney Kenneth Cohen requested that Keishan be locked up in Apalachicola to restore his competence.

“How many robberies does someone have to commit before you say this program is not going to work?” Cohen asked the boy’s Fort Lauderdale therapist.

Keishan was sent to Apalachicola for the first time in June 2012, records show. He’s been there a total of about 32 months since.

$130,000 The cost of a bed at a residential treatment program for a youth like Keishan Ross.

By 2015, some psychologists had concluded Keishan’s intellectual disability and mental illness rendered him “not restorable” — meaning he could never be tried for the many offenses that had piled up. “There is no treatment for borderline intellectual functioning,” one wrote.

Fort Lauderdale psychologiest Jeffrey I. Musgrove performed his fifth evaluation of Keishan in November 2016. The boy, then 16, had just been returned from Apalachicola. Within hours, he had fought with another youth, Musgrove wrote, and when guards tried to calm him down, he “kept banging on his cell door, kicking and cursing at staff.”

Musgrove described Keishan as “slightly overmedicated,” which rendered the teen particularly docile. Though Keishan put “forth what would be, for him, his best effort.” Musgrove wrote that he did “not seem to be able to do much more than parrot back the terms and concepts he has heard about.”

As for participating in his defense, Keishan was under the impression that he could not plead innocent if he “really did the crime,” Musgrove wrote. “I found it particularly telling when Keishan remarked to me, ‘It doesn’t matter anyway. I’m always guilty.’”

“I just wanna go home,” the boy said.

Musgrove concluded: “It is my very certain clinical opinion that Keishan is incompetent to proceed, and that his limited IQ and ongoing problems with paying attention and concentrating present insurmountable obstacles to his ever becoming adequately competent in the future.” He underscored the statement.

Off Keishan went, back to Apalachicola, where, within a week, the program administrator asked Orlando to take him back again. In Broward, the psychologists all said that Keishan was too disabled to stand trial. In the Panhandle, “it is the opinion of AFYC’s professional staff that K. Ross is competent.”

So Keishan bounced back to the lockup, where he remains.

[This story was originally published by MiamiHerald.]

[Photo credit via Flickr.]