Disasters' Great Divide: How COVID divided Sonoma County's health

This project was originally published in The Sonoma Index-Tribune with support from our 2023 California Health equity Impact Fund.

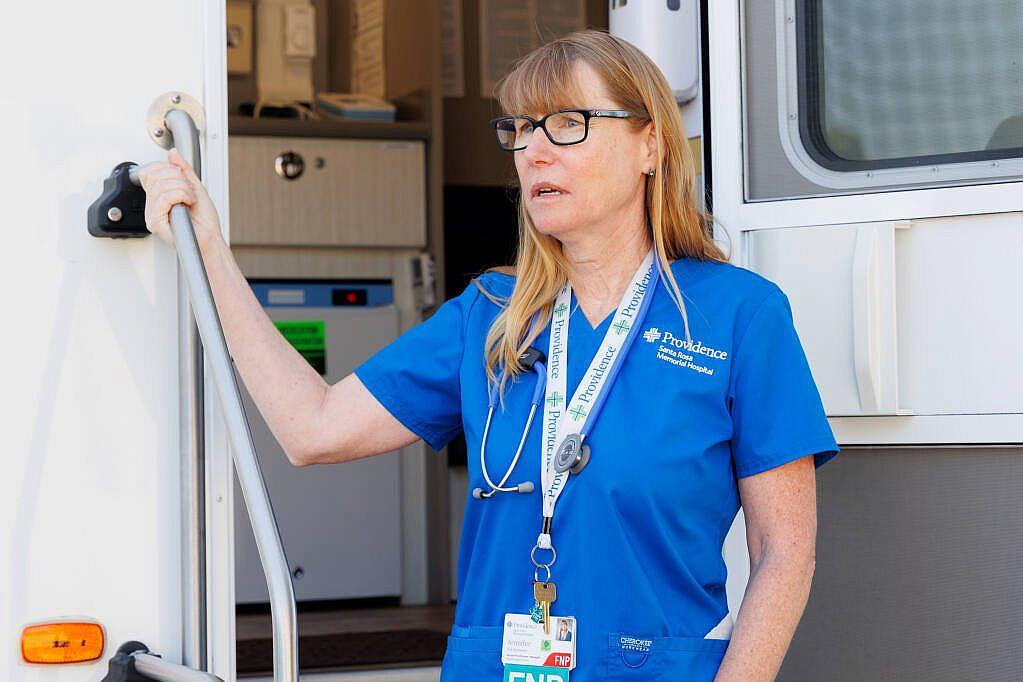

Jennifer Eid-Ammons stands at the entrance of the Providence Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital Mobile Health Clinic in the La Luz Center’s parking lot on July 21, 2023.

Abraham Fuentes/ For the Index-Tribune

Going back to normal after the pandemic was never an option, especially for the families who still feel its effects.

As the tide of the virus and COVID regulations has faded over the past year, residents have been left to grapple with its enduring trials -- some more than others.

“It was clear that there were vulnerable populations that are a reflection of structural racism, structural inequities that had been there for probably a couple of centuries,” Tim Gieseke said, a former medical director of the Santa Rosa senior living facility Springs Lake Village, who came out of retirement to research COVID-19. “Those on the bottom end, who are working multiple jobs, were the ones that were most affected by COVID.”

While many have adapted to the changes wrought by the pandemic — normalized nasal plunging for COVID tests and work from home — many of its longterm harms remain, magnifying the inequities that plague Sonoma County.

In housing, overcrowded homes struggled to quarantine family members and recorded higher infection rates. In education, low-income children fell further behind than their peers. Meanwhile, the mental health care system has been taxed by burnout and turnover just as the needs of the community began to skyrocket.

“There's always been natural disasters. But the pandemic added on to that,” Karin Sellite said, a Sonoma County client care manager who coordinates mental health resources and provides behavioral health services. “That's a unique experience that we haven't really had to deal with, and I think that has very disproportionately impacted kids... Over time, we may see that natural disasters are creating some specific mental health reactions that we hadn't anticipated, in addition to PTSD and trauma and grief.”

When Sonoma County entered the COVID-19 state of emergency in March 2020, it was the fourth time the county called for a federal state of emergency since 2017 in a region known for wildfires, flooding and public safety power shut-offs. The direct impacts, such as hospitalizations, and the indirect effects, like school lockdowns, have receded but continue to cast a long, cold shadow.

The Curative COVID-19 testing kiosk was full of potentially sick residents at the Fiesta Plaza on Highway 12 in Boyes Hot Springs on Monday, Jan. 3, 2022.

Robbi Pengelly/Index-Tribune

“It exposed that for years public health was almost nonexistent,” Gieseke said. “Now, the resources are going away, maybe too quickly in some sense of the word, but that's how life moves. We are a crisis-oriented culture.”

While infection from the coronavirus was unprejudiced, the opportunity for infection was not, Gieseke said. This made the pandemic comparable to a “natural experiment” by public health researchers, demonstrating how a virus moves across the spectrum of income and race.

“Unfortunately, you can say it's a great experiment, but you can also say it's like setting up a nuclear bomb because it's so complicated,” Gieseke said.

Virus spreads through cramped housing

As Sonoma County health officers advocated for protections like masking and social distancing in the spring of 2020, packed low-income households in places like Boyes Hot Springs, where multiple people can share a bedroom, questioned what to do.

“They wanted to protect other (household) members, especially if there were grandparents in the house. They were really concerned about spreading the virus,” Providence Memorial Mobile Health Clinic nurse practitioner Jennifer Eid Ammons said.

But residents faced a Catch-22, she said: “Do you isolate the grandparents, or do you isolate the person with COVID?”

Jesika Quintal (left) and Jennifer Eid Ammons(right) set up the Providence Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital Mobile Health Clinic in the La Luz Center’s parking lot in Sonoma on July 21, 2023.

Abraham Fuentes/ For the Index-Tribune

A national look at COVID shows a pandemic of the poor. In April 2022, The Poor People’s Campaign, an advocacy group against income inequality, released a study analyzing the influence of wealth on COVID-19 deaths, separated by county.

“While vaccines will prevent the worst impacts of COVID-19, they will not inoculate against poverty,” the report concluded.

“In early summer, Latinos accounted for as much as 77% of all COVID-19 cases, though they only comprise about a quarter of the county’s population,” The Press Democrat reported in October 2020. The article followed a state mandate to reduce the impact on minorities and disadvantaged communities — Sonoma was one of four Bay Area counties called out for its inequitable handling of COVID.

“During the third phase, death rates were 4.5 times higher in the group of counties with the lowest median income compared to those in the group with the highest median income. Death rates were five times higher in these low-income counties during the Delta variant,” the Poor People’s Campaign report stated.

As part of her job, Eid Ammons travels to low-income communities throughout Sonoma County, forming relationships with residents who were often the least physically prepared to “social distance” and the least financially prepared to seek health care.

“They know that if they can't afford medication… that anybody would just go buy at Safeway or CVS, they know ‘Oh, I'll wait for the mobile clinic to come,’” Eid Ammons said. “Because we could give them masks, we could give them COVID tests, we could give them cough syrup, we could give them inhalers.”

The clinic’s options expanded during the pandemic when COVID resources were offered to patients who lost their jobs or were ineligible for relief funds due to their citizenship status, Eid Ammons said.

Jackie Williams (left), Jesika Quintal (middle) and Jeniffer Eid-Ammons (right) setting up the Providence Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital Mobile Health Clinic in the La Luz Center’s parking lot in Sonoma on July 21, 2023.

Abraham Fuentes/ For the Index-Tribune

Overcrowding is directly linked to health and quality of life, according to the National Library of Medicine, which explains why the neighborhood has one of the poorest human development index scores in Sonoma County. A 2019 Countywide Assessment of Fair Housing by Sonoma County Community Development Commission found one in five renters in Boyes Hot Springs and El Verano live in overcrowded housing, which is defined as 1.5 people or more per room.

“There is no justifiable explanation, there's no sort of morally acceptable explanation for the stark differences between the city (of Sonoma) and the Springs in terms of not just overcrowding, but also educational attainment, health status, income and life span,” Caitlin Cornwall said, a project director with the housing advocacy group Sonoma Valley Collaborative.

To hear from those impacted by overcrowded housing during the pandemic, the Sonoma Valley Collaborative held a joint town hall in 2022 with La Luz Center. A Sonoma Valley sophomore named Esme said her family of six lived in a small trailer, where a lack of privacy hindered her sleep and ability to complete her school work.

“My daily-life obstacles are a problem,” Esme said, “because if I don’t have privacy, that limits my ability to study and have a place to do my school work without interruptions.”

There was concern about the government’s response.

“I don’t think decision makers understand how not having a stable home can mess with a young person’s mental health and well-being,” Litzy Mora said, who was a Sonoma Valley High senior at the time.

During months of distanced learning, these students became aware of the divisions in their own community.

“Why a lot of the kids were depressed and were upset or felt isolated, was because they would see inside the homes of some other students and they would just see a different world,” Eric Gonzales said, the vice president of the Boys & Girls Club of Sonoma Valley’s Teen Services.

Mentally exhausted and overtaxed

Months of lockdown and isolation shredded the mental well-being of many, particularly children, who saw their routines rocked by pandemic regulations.

“Self-doubt, confidence, the loneliness, the self-esteem issues that we're seeing, it's all kind of hindering the youth,” Gonzales said as students returned to the after-school program at the Boys & Girls Club post pandemic. “They were all so developmentally behind, socially behind as well... behaviors that we would see in our middle school program, we would see that with our high schoolers.”

Jesika Quintal checks the blood pressure of one of the first patients of the day.

Abraham Fuentes/ for the Index-Tribune

The Club began looking at mental health programs after the 2017 wildfires to support its members, many of whom were stricken with anxiety and depression, Gonzales said. But COVID “pushed us over the edge.”

“Seventy-five percent of the students that we serve are Hispanic and, coincidentally, another 74% of the kids that we serve live in the Springs area which is classified as one of the lower-income sectors of Sonoma,” Gonzales said.

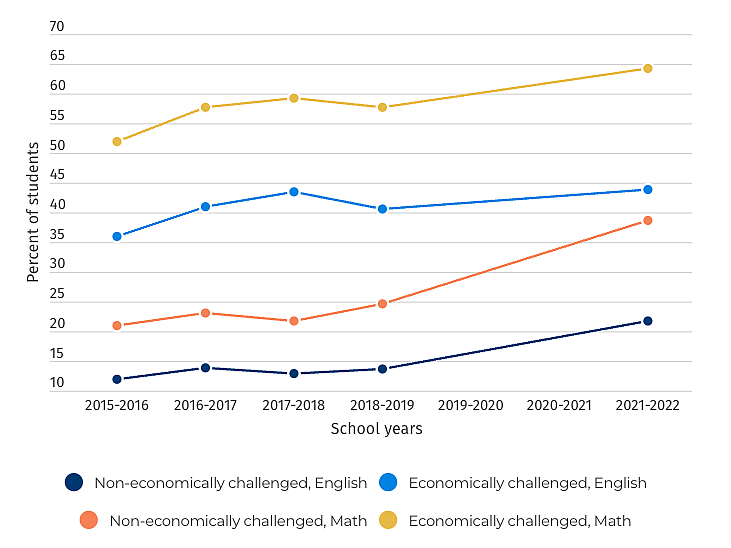

Statistics from Sonoma Valley Unified School District show a drop in English and math test scores across all household incomes, but some students felt the situation more viscerally. The learning loss for Latino students, those with disabilities, students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds or English learners was most significant, according to 2022 California School Dashboard findings.

Income vs. test scores in Sonoma Valley Unified School District

The number of students who did not meet California testing standards for English and math grew after Sonoma Valley students were battered by wildfires, power safety shutoffs and COVID-19.

Source: California Department of Education

“(Children have) spent so long being completely and abruptly cut off from their social support, and having to sit at home to do their schooling. That's not something that we’ve dealt with before,” Sellite said.

By November 2020, a survey by the nonprofit YouthTruth found that seven in 10 Sonoma County students felt anxious about the future — the biggest concern being educational struggles.

“Certainly, some kids are going to bounce back and they're going to be OK. What I could say with confidence is that kids who maybe were struggling a little before this disaster, a pandemic can kind of push them over the edge from struggling a little to really just kind of floundering,” Sellite said.

Momentum is building to address the mental health crisis. Sonoma County approved $28 million toward mental health in January to address the long-lasting effects of recent disasters such as the pandemic. The Hanna Center, a Sonoma Valley nonprofit, opened its own Mental Health Hub in May to serve communities across the region regardless of their ability to pay. And a group of 17 Sonoma Valley organizations are organizing to work in tandem to address residents’ psychological well-being.

But despite these investments in mental health services, meanwhile, the county’s mental health workforce shrank and become more vulnerable.

Chelene Lopez works on a pamphlet for the mobile clinic inside the kitchen of La Luz Center in Sonoma on July 21, 2023.

Abraham Fuentes/ For the Index-Tribune

“This county, because of the trauma from the fires, and then the trauma of having to be enclosed or lost a job, we're seeing much more stress-related issues around depression and suicide,” said Chelene Lopez, a community program educator with Providence Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital. “It may not be your lungs. But mental health is where we're falling way behind of what needs to happen.”

The county has a 28% vacancy rate for mental health provider positions, Sellite said.

“We've had all these disasters and the pandemic and all these problems that are increasing the need for mental health treatment in the community, and we have less staff to serve them,” Sellite said.

Life with long-COVID

For residents who were diagnosed with long-COVID — the mysterious lingering form of the virus which has perplexed scientists — the virus continues to cause disruptions and distress.

Lopez’s husband, who asked to not be identified for the article due to the stigma of long-COVID, won a marathon in his hometown and played soccer in his younger years. As he aged, he developed heart disease, making him high risk for COVID complications. It was August 2020 when he contracted the virus.

“The reason that we found out that he was positive was he was so tired, he was just exhausted,” Lopez said. “Recoup took him probably a month to get back up and running and getting to doing his normal thing. But after that, he was never the same.”

Lopez’s husband lost his sense of taste but otherwise faced a “mild case” of COVID-19. Yet as his recovery bled on for weeks and then months, Lopez noticed her husband’s coordination slipping — he began bumping into her.

“We would be in the kitchen, and he would try to go around me and he his body had no control,” she said. “So it's changed his life. He doesn't work anymore. He can't work.”

Now 60, Lopez’s husband is left struggling with lingering health concerns.

Sarah Rechford (left) and Jesika Quintal (right) look at Rochford screen on who will be helping each patient inside of the Providence Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital Mobile Health Clinic in the La Luz Center’s parking lot on July 21, 2023.

Abraham Fuentes/ For The Press Democrat

“The problem of long-COVID is it's really a disorder of immune systems,” Gieseke said. “There's something that has triggered the immune system in a way it's not supposed to be triggered. And so it falls into categories like chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia.”

Sonoma County recorded its first case of COVID-19 on March 2, in a passenger who departed from a Mexican voyage on a Grand Princess cruise ship. Over the past three and a half years, the virus has adapted and mutated. COVID-19 has killed 616 people in Sonoma County and hospitalized at least 116,607 residents — nearly 1% of the entire population of Sonoma County, according to state records and the Sonoma County COVID-19 dashboard as of Aug. 15.

Public health officials continue to be wary of the embedded threat of COVID-19 and its lasting impact on individuals and communities. Over the past two months, the California Department of Public Health has recorded marked rise in COVID-19 cases statewide. Sonoma County hospital are recording increased hospitalization and reinstituting masks mandates for staff amid the uptick, though numbers remain low compared to the early months of the pandemic.

Three years in, and while concern over COVID has dropped markedly for some, others are left floundering in its wake.

“There's people with long-COVID, but there was a lot of stress. And people lost their jobs. And lost a lot of things. Lost people,” Lopez said. “So how we're dealing with this now? I think we're gonna see the effects 10, 15, 20 years down the line.”