Daysi and her family did not have access to Spanish-language emergency notifications from local authorities. A Sonoma County rapid needs assessment after the fires found that 12% of households surveyed preferred emergency communication in languages other than English. Without the full knowledge of the impending fire, the Carreños waited to evacuate and inhaled smoke as the emerging disaster raged and coalesced around them.

“We saw our neighbors leaving their homes and running around. We would hear the honking of horns as people were leaving. That's when we knew this was not OK,” Daysi said. “We went outside and saw what was happening. It was inevitable. The winds that were so fierce. The winds, the ash, the smoke that filled the air.”

Daysi rushed from her home, loading her five-member household into one car in an effort to stay together during the disaster. As they packed in, Daysi heard fire trucks and hoped they would reach the blaze before it could consume her home.

According to a rapid needs assessment by the Sonoma County Department of Health Services, 40% of households experienced a traumatic event like being separated from a family member, facing the threat of death, or suffering a significant injury in the 2017 North Bay fires.

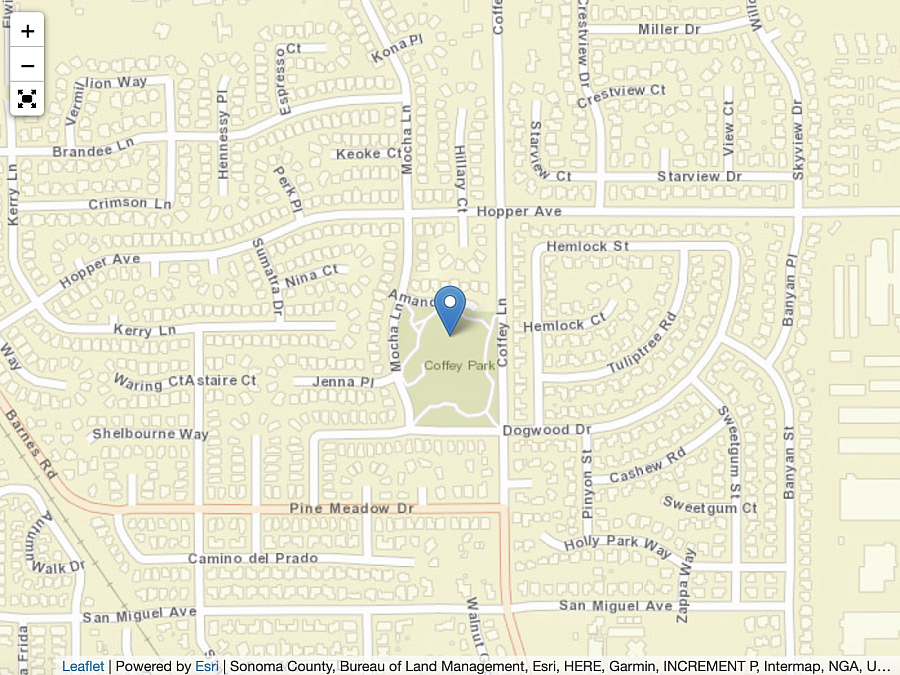

Coffey Park in Santa Rosa, Wednesday Oct. 25, 2017, after being leveled by the Tubbs Fire.

(Kent Porter/The Press Democrat)

They were part of an estimated 200,000 people forced to evacuate due to a combination of the Tubbs and Nuns fires, which killed 40 people across the North Bay and destroyed upward of 5,500 homes.

The Carreños family fled to Roseland, an impoverished community in Santa Rosa, where Carlos’ family lived. After settling his family, he drove back to Coffey Park to grab photo albums and computers left behind in the rush to evacuate, but the scene he found was grave.

“This is horrible here right now. There's fire everywhere,” Carlos told Daysi over the phone. “I don't think we're gonna be able to save the house.”

The Carreño family

Daysi Carreño, the mother of the family, immigrated to the United States from Michoacan, Mexico, 24 years ago and has worked in many of Sonoma County’s driving industries: hospitality, restaurant service and even T-shirt production.

Her husband Carlos, their eldest daughter Ashley, their middle daughter Dayren and their youngest daughter Mili each were affected by fires differently. Carlos and Dayren sought therapy. Mili was mostly too young to remember the decimation of their home. And Ashley studied environmental science at Chico State in response to the fires that took her home and volunteered with students to create evacuation bags.

Lingering smoke

The fires left Daysi’s in need of medical care after her asthma was triggered by the smoke. Today, her daughters suffer from anxiety and PTSD sparked by the smell of smoke.

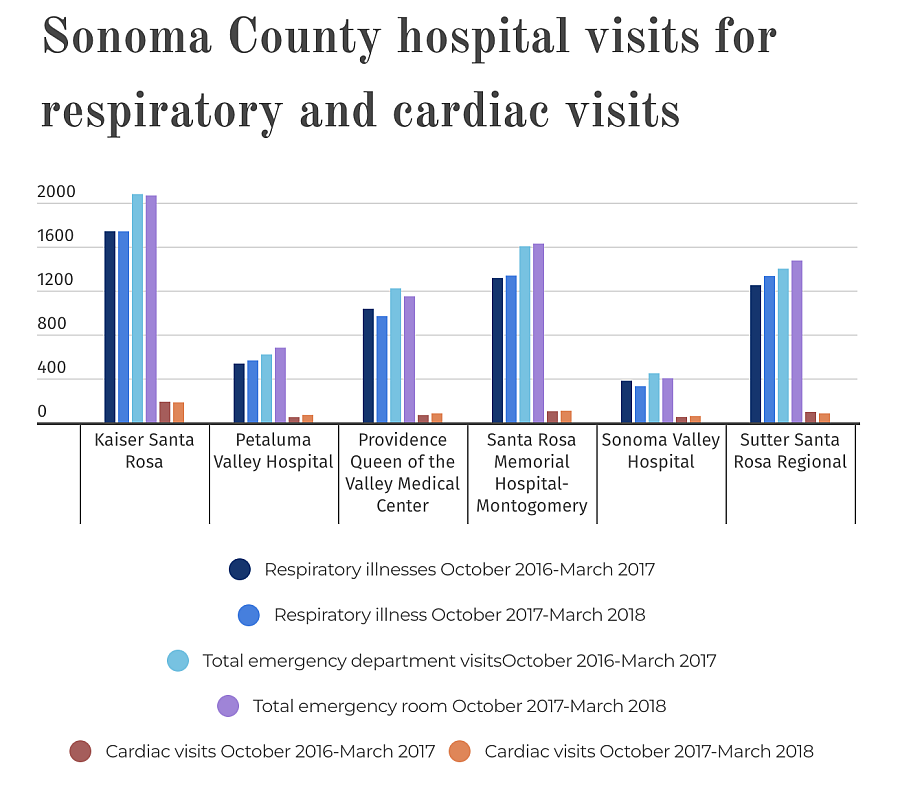

Data from the California Department of Health Care Access and Information show the 2017 fires led to a spike in visits at Sonoma County hospitals for respiratory and cardiac illnesses, which most commonly afflicted low-income residents without health care, outdoor laborers and older residents with preexisting conditions, Heft-Neal said. That’s in addition to the complex trauma and depression often associated with victims of wildfires.

In the six months following the fires, Sutter Santa Rosa Regional Hospital recorded a 6.6% rise in the number of visits for respiratory illnesses from the year prior. Petaluma Valley saw a near 10% increase in the total number of admissions, in part due to the large number of residents who were evacuated to that city, one of only a few in the county that did not burn in 2017.

Data: California Department of Health Care Access and Information

Graph: Chase Hunter/Index-Tribune

But the lingering physical complications represent only half the story for the Carreños.

Daysi’s middle daughter, Dayren Carreño, 20, is haunted by the ghosts of the fires she’s witnessed. She’s filled two binders with photos and important documents which she keeps close each fire season. It’s preparation in case she ever has to evacuate again.

“I was diagnosed with depression, PTSD and anxiety from my therapist,” Dayren said. “And even though it's eased up a bit from the time that I was diagnosed, it's still in the back of my brain when one little word can trigger it.”

Ashley, Daysi’s eldest daughter, also has flashbacks to that terrible night whenever she smells smoke.

The myriad health challenges in Sonoma County that stem from natural disasters have begun to impact the health care system and its labor force. Karin Sellite, a client care manager with the county’s mental health department, said growing needs during and after natural disasters have created fissures in the system and made it less adept at responding to subsequent disasters.

Sellite administers mental health care to Medicare and MediCal recipients in Sonoma County, people who are often low-income, older or disabled. Since the fires of 2017, the number of patients seeking health services has increased 15% while the number of county mental health workers has declined by more than 20%, Sellite said.

“We've had all these disasters and the pandemic and all these problems that are increasing the need for mental health treatment in the community, and we have less than less staff to serve them,” Sellite said.

This hits especially hard for those who can’t afford private therapy, which can cost upwards of $150 a session.

Children represent a unique situation regarding mental health. Innocence can be bliss: Young children too young to understand the seriousness of natural disasters are often resilient. But children mature enough to comprehend the seismic connections between wildfires and housing loss have experienced an uptick in depression, anxiety and PTSD, Sellite said.

“It goes beyond only looking at the mental health impacts, but the impact of natural disasters in taking away people's homes and securities, coupled with the physical impacts that wildfires have for example,” Sellite said. “There's a connection that we're going to see more of as we go along, in mental health conditions that have resulted from this.”

Daysi Carreño’s eyes well up with tears thinking about what her family has lost. But Mili only remembers fragments of her life before the Tubbs Fire.

(Genesis Botello/Index-Tribune)

One in five youth who had experienced significant impacts of fires or the COVID-19 pandemic considered suicide in the past year, rates two to three times higher than years prior, according to an equity study called Portrait of Sonoma County.

Structure is integral to the mental well-being of children, Sellite said. Going to school, playing after-school sports and eating dinner with their families help regulate what “normal” is. Fire evacuations, smoke days and Public Safety Power Shutoffs have dismantled those routines.

“As we follow cohorts of kids who have been impacted by our recent disasters, certainly, some kids are going to bounce back and they're going to be OK,” Sellite said. “The kids who maybe were struggling a little before. A disaster, a pandemic, can push them over the edge.”

From ashes

After wildfires incinerated thousands of homes across Sonoma County, increased housing scarcity caused rental prices to rise, and many workers like Daysi were forced to travel farther to find affordable housing.

The Carreños eventually applied for an R.V. at the Sonoma County Fairgrounds where FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) managed an emergency center after the fires.

While Daysi herself could not apply for housing and cash assistance due to her undocumented status, her daughter was eligible as an American citizen.

“As someone who doesn't speak the language and doesn't have a Social Security number, getting access to those resources is incredibly difficult and the county was absolutely not prepared to provide translation and interpretation for that,” Daysi said.

From that R.V., the family watched as the Camp fire destroyed the town of Paradise. They were not immune to the fire’s far-reaching effects. Smoke traveled through the air, into their R.V., across the Bay Area and throughout the Midwest.

“Our lungs were infected because the R.V. is really not a place to live,” Daysi said. “And so when we experienced the smoke of the Paradise fire, it was difficult for our lungs living in the R.V.”

Insurance gaps

Fire risk has caused fire insurance to become increasingly unaffordable to low-income renters, according to the housing advocacy organization Sonoma Valley Collaborative. For those residents, there are two options: Go without fire insurance despite the risks or move away.

“The market is not going to produce the housing that we need at all, quite clearly,” Caitlin Cornwall said, the project manager for the Collaborative. “There is this positive feedback between the very high cost of living that causes displacement of lower-income and middle-income people.”

Nonrenewal insurance rates more than doubled in 2019 in ZIP codes with the highest wildfire risk, according to a 2022 report by Resources for the Future, a nonprofit research organization. In 2021 alone, insurance companies declined to renew 241,662 residential policies, according to the latest data from the California Department of Insurance.

The rate of nonrenewal has crept upward since 2015, and as a result, enrollment in the state’s safety net insurer FAIR Plan has grown from 126,709 to 272,846. It is a less-than-ideal option with high rates and restricted coverage despite some recent reforms, and advocates warn its continued expansion is unsustainable.

The Carreño family, Carlos, Daysi, their youngest daughter Mili, their middle daughter Dayren and their oldest daughter Ashley walk toward the property which replaced their home after they were unable to move back after the mental toll of the Tubbs Fire.

The Carreños have found a new home, but it lacks fire insurance. They’ve also found a new community and new schools. But the memories and comforts of their old neighborhood — the best houses to “trick or treat” at on Halloween and the lights that filled the block during Christmas — continue to slip away.

“Sonoma County has had a lot of natural disasters over the last five years or so and we aren't able to recover from the last one before the next one hits,” Sellite said. “The stress and the trauma that creates in individuals and in the community as a whole is pretty significant. And it just keeps building.”