Disasters' Great Divide: Sonoma County heatwaves hit seniors, farmworkers hardest

This project was originally published in The Sonoma Index-Tribune with support from our 2023 California Health Equity Impact Fund.

In a Boyes Hot Springs house where the fan is broken and too expensive to fix, residents Ruomaldo Argota and Marta Maria Farias escape the heat by covering the windows on a stifling July day.

(Darryl Bush / For The Index-Tribune)

On a street two miles north of the tasting rooms that dot the Sonoma Plaza, the sidewalk crumbles into dirt paths and mustard weeds that force pedestrians to the asphalt shared by passing cars. Boyes Boulevard, the namesake street of Boyes Hot Springs, offers a spectrum of wealth in Sonoma Valley from the luxurious Fairmont Sonoma Mission Inn to the modest pueblo homes of residents like Marta Maria Farias, 59, and Ruomaldo Argota, 70.

Their living room feels like a budding fever on this stifling June afternoon in a home where three generations of their family — 10 people total — live with little respite from the heat of summer. A portrait of the Virgin de Guadalupe hangs from an exposed brick wall next to a broken air conditioning unit.

“That’s fine, it keeps the electricity costs down,” Argota said, wiping sweat from his low, thick brow.

Marta Maria Farias, Ruomaldo Argota and their grandchild lie on their living room couch, staring at the ceiling fan that’s broken but too expensive to fix. Behind them to the left is a broken air conditioner. During summers, the inside of their home commonly reaches above 95 degrees.

(Chase Hunter/Index-Tribune)

Yet despite more intense and regular heatwaves, low-income residents and outdoor workers remain unprepared for new extremes which threaten their health. Air conditioning in Sonoma County, once thought of as a luxury, is becoming a necessity as temperatures break new highs, displaying an uncomfortable inequity between those who can afford to cool down, and those who can’t. It threatens to exacerbate heat-related illnesses in low-income communities and the workforces who support the wine, tourism and hospitality industries of Sonoma County.

For Farias and Argota, “You just deal with it,” Farias said.

The Bay Area has mostly been insulated from the deadly heatwaves that have struck across the globe. But the combination of global warming and extreme weather systems like El Niño create the potential for a deadly heatwave in Sonoma County, according to environmental experts. When it comes to heat-related illnesses and fatalities, elderly residents, low-income communities and outdoor workers are most at risk.

“As I get older, after all the years that I’ve worked in the fields — plus when I was in Mexico I worked outside. It's just getting to me,” Argota said. “It's just catching up.”

In the fields

Outdoor workers, exposed to the sun and elements, face the most intense health impacts of heatwaves. Vineyards offer little respite from the sun during months of pruning and picking. And grape growing businesses are reluctant to hire back the people most at risk in heatwaves, particularly elderly workers like Argota and Farias. They feel forced to choose between their health and their livelihood.

“It's difficult to think of not being able to work because everything is so expensive,” Farias said. “Paying other bills might be a little easier to avoid, but rent is unacceptable.”

Ruomaldo Argota works full time in the vineyards, while his wife Marta Maria Farias works part time. They are pictured on April 16, 2022.

(Photo: Maria Luz Rodriguez)

Farias and Argota are two of Sonoma County’s 10,000 farmworkers, of which, an unknown number are undocumented like them. These workers are most likely to end up in harsh working conditions, as lax safety regulations offer little protection.

In July, Sonoma County vineyard Mauritson Farms agreed to pay $328,077 to settle a labor dispute with 21 farmworkers who alleged “failure to give breaks and lunches, lack of shade and abuse by supervisors.”

“There's a long history of work studying the impact of extreme temperatures on farmworkers, and they tend to be one of the most vulnerable populations in terms of extreme heat,” Stanford University researcher Sam Heft-Neal said. “Any population that has to be outside is vulnerable, and that would include farmworkers and the unhoused.”

Due to his age and health, Argota is especially vulnerable, plagued by anemia which leaves him at greater risk of heat-related illnesses. He experienced the effects of extreme heat firsthand while working in vineyards last summer.

“I was out in the fields and I was feeling faint, I was feeling weak,” Argota said. “And that’s when I found out I had anemia.”

Ruomaldo Argota and wife Marta Maria Farias sit in the heat of their Boyes Hot Springs home on Wednesday, July 19, 2023 in Sonoma.

(Darryl Bush / For The Index-Tribune)

Outdoor workers and seniors will be the demographics most impacted by heatwaves in coming years, susceptible to “hyperventilation, dyspnea, dehydration, as well as cardiovascular events” after prolonged exposure, according to a 2018 study published in the Journal of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology.

As temperatures increase, the body’s systems to dispel heat begin to break down. The cooling effect of sweat lessens as humidity increases in high temperatures, preventing the sweat from evaporating. The body also pushes blood to the extremities to cool down its core, but the resulting drop in blood pressure reduces the amount of oxygen and nutrients that go to key organs. A 2020 study published in the National Library of Medicine found 36% of people diagnosed with heat stroke suffered an acute kidney injury.

“When a person cannot avoid prolonged exposure to extreme heat, their core temperature rises, heightening the risk for heat exhaustion, heat stroke and, potentially, death,” said Dr. Michele Barry, the director of the Center for Innovation and Global Health at Stanford University. “Heat also impacts mental health, for instance driving depression, violence and possibly also risk for suicide in those such as farmers whose livelihoods are impacted by heat and drought.”

Barry has researched the impact of heatwaves and other extreme weather events for more than a decade through the lens of inequality across the globe. And more recently, she’s looked at how extreme weather jeopardizes the health of outdoor workers.

Harvest workers carry full bins of pinot noir grapes to the tractor bound for the Martin Ray Winery in Sebastopol, as the 2022 grape harvest gets underway.

(Chad Surmick / The Press Democrat)

“Outdoor workers – like wildland firefighters, agricultural workers and people working in construction – are most impacted by extreme heat. These workers are at increased risk of acute heat-related illnesses, as well as long-term health impacts,” Barry said. ”Heavy physical exertion in heatwaves can be lethal. Many, especially those in lower-wage jobs, don’t necessarily have the option to forego days of work and pay.“

The cost of missing work goes beyond health, but is no less debilitating, said Davida Sotelo Escobedo, the communications and research coordinator for North Bay Jobs with Justice, a Sonoma County social justice organization focused on farmworkers.

“With a deepening climate crisis and extreme weather, farmworkers are on the frontlines of all those extreme weather events,” Escobido said. “Hazard pay and disaster insurance is beyond the question of what farmworkers deserve.”

Hazard pay and disaster insurance for workers would help make up lost wages from canceled work opportunities for farmworkers. These protections have not yet been widely adopted by the agricultural industry, however.

While Sonoma County Board of Supervisors approved an evacuation access program to keep farmworkers from working in dangerous wildfire conditions, no guidelines exist for heat. The state of California requires a quart of water and shade every hour for outdoor workers, but federal work protections from weather are still being considered by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration office.

For Argota, he’ll work when he can to support his household. But Farias’s concern grows each time he takes to the vineyards.

“Because of our age and our medical problems, we have a lot of doctor’s appointments. And because of our age, we’re not called as readily,” she said. “And then, even if we are called, the heat and having to bend over constantly make it difficult.”

Marta Maria Farias and husband Ruomaldo Argota stand outside their home, Wednesday, July 19, 2023 in Sonoma. Ruomaldo and Marta, have been plighted with heatwaves without the use of an air conditioner or fan that works.

(Darryl Bush / For the Index-Tribune)

Marta and Ruomaldo

Marta Maria Farias, 59, and Ruomoldo Argota, 70, are undocumented immigrants who live in Boyes Hot Springs and work in the agricultural fields in the area. Ruomoldo has anemia and he has experienced fainting during heatwaves. Their rental property is not equipped with air conditioning and their living room fan has remained broken for 3 years due to the high cost of utility bills. Extreme weather events impact their ability to work in the fields, yet they often push themselves to work despite the health risks.

Feeling the heat

The workplaces of farmworkers — the vineyards of Sonoma County — are only becoming less hospitable. Sonoma County faced its hottest year in its history in 2020 — bringing with it new temperatures that have rewritten the record books with increasing frequency.

Sonoma County's average summer temperature in the past five years has been 1.7 degrees (0.94 Celsius) warmer than it was from 1971 through 2000, according to a Washington Post analysis of data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. While the progressive rise of temperature is important to monitor climate change, it does not capture isolated heatwaves and heat domes that threaten people and animals alike.

The city of Sonoma matched its all-time record high of 116 on Sept. 6, 2020. And in Santa Rosa, the population center for Sonoma County, the former all-time high of 113 degrees set in 1913 was toppled by a 115-degree day on Sept. 6, 2022. According to Bay Area data since 1900, over 25% of record highs at the National Weather Station in Napa have been set since the year 2000.

“We once had four seasons. Spring, summer, winter and fall. And now it feels like it's fire season and drought season,” Woody Hastings said, an energy and environmental analyst at the Climate Center, an environmental nonprofit based in Santa Rosa. “How are we going to adapt to these changes that are all we're already experiencing?”

While heat does not leave the wake of destruction seen in other weather disasters, it is perennially the deadliest weather in the United States — responsible for more fatalities than tornadoes and hurricanes combined — contributing to the deaths of more than 600 people per year on average, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

When temperatures skyrocketed in Mexico in June, 112 people perished from heat exposure, the vast majority of whom were over age 65.

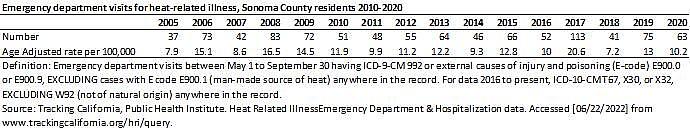

A graph of the annual number of emergency room visits for heat-related illnesses in Sonoma County from 2005 to 2020, according to the Sonoma County Department of Health Services.

(Sonoma County Department of Health Services)

Sonoma and other North Bay counties, including Napa, Solano and Marin, all face higher rates of emergency room visits for heat-related illnesses than other regions in the Bay Area. In Sonoma County, 113 emergency room visits were recorded in 2017 — nearly double the 57 visits per year on average for heat-related illnesses between 2005 and 2016.

Heatwaves that were once a 1 in a 1,000 years events are expected to hit the Pacific West with increasing frequency in the years to come, Hastings said. When these rising global temperatures converge with weather patterns like El Niño, they threaten to not just break records but also lead to mass death events.

No way to cool off

As Sonoma County adjusts to the extreme temperatures of the 21st century, many low-income residents still live in homes built for the 20th century. Argota said their Boyes Hot Springs home often gets to 95 degrees or hotter during the summer.

Rachel Morello-Frosch, a professor in the Department of Environmental Science at the University of California at Berkeley, said Bay Area homes are rarely built to protect against extreme temperatures, largely due to its historically temperate climate.

“In the Bay Area, we don't experience a lot of heat so when we get it, it's really intense,” Frosch said. “Our built environment, our homes, are not necessarily particularly well insulated, which people often think about insulation that protects you for warmth. But insulation can also do a lot to prevent homes from overheating.”

According to surveys from the California Energy Commission, half of households in Climate Zone 2 — which includes Sonoma County — do not have any form of air conditioning.

“I don't think there are many places around here that you can rent that have A/C unless they're fancy condominiums or townhomes,” said Patricia Galindo, the family service coordinator at the Sonoma Valley nonprofit La Luz Center, which serves the immigrant community.

Ruomaldo Argota and wife Marta Maria Farias can’t escape the heat at home or at work.

(Darryl Bush / For the Index-Tribune)

Stifling heat can be exacerbated by the cramped housing in Boyes Hot Springs – the most overcrowded area for housing in Sonoma County in 2019, according to a January 2022 report by Generation Housing, an affordable housing advocacy organization.

The relationship between limited air conditioning and cramped housing is part of the reason why the Springs had one of the lowest human development index scores in Sonoma County at 96th out of 99 neighborhoods, according to the 2014 Portrait of Sonoma report. The human development index takes a holistic look at health while considering education, income, health and other environmental factors such as utilities and housing.

Yet even as temperatures rise to new heights, households like Farias and Argota’s sit without any mechanism for relief.

While the Springs neighborhood improved to 84th in the 2021 Portrait of Sonoma report, the Valley’s inequity is clearly mapped. Just five miles west, the East Sonoma Mountain neighborhood ranks fifth in quality of life metrics, with a median income $20,000 higher than the Springs.

Heat islands

The increasingly oppressive heat punctuates the importance of trees and the cooling shade they provide. Decades of inequitable investment in infrastructure have created heat islands in industrial areas and low-income communities throughout the county, where heatwaves can be felt more brazenly.

“Heat islands are basically a geographic area where there’s a lot of variability in apparent temperature,” Morello-Frosch said. “Heat islands can form in places where you have impervious surfaces, so that can be in certain rural areas, depending on what the built environment looks like.”

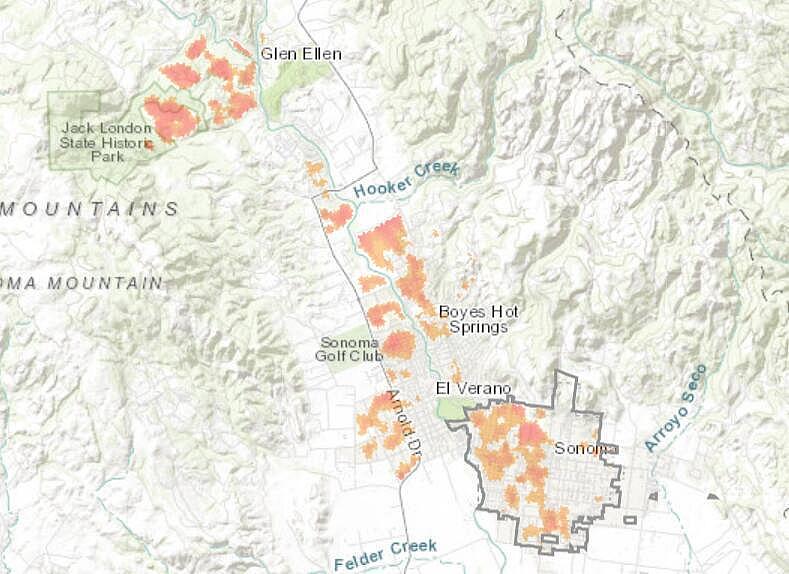

A map of the heat islands in Sonoma Valley from the Trust for Public Land. Minor heat islands are represented in yellow and more significant heat islands are shown in red.

(Courtesy of the Trust for Public Land)

Geographic data from the Trust for Public Land provides a detailed view of the “heat islands” in Sonoma Valley — specifically, the west side in the city of Sonoma and numerous places in the Springs — caused by denser urban infrastructure and a lack of tree cover.

Neal Ramus, the director of community engagement at Sonoma Land Trust, has used this tool to look at how urban design contributes to heat islands in Sonoma County cities, including neighborhoods in Sonoma, Petaluma, Santa Rosa and Rohnert Park.

“Urbanization does a bunch of things for temperatures,” Ramus said. “Everything from concrete and asphalt coverage increases temperatures. Inside cities, there's often less vegetation, there's less trees that block the sun.”

The combination of these factors can expose these residents to higher temperatures and require greater energy use to insulate themselves from heatwaves.

The western portion of Boyes Hot Springs is studded with heat islands on the Trust for Public Land map, where average temperatures can be 2-3 degrees hotter than the surrounding areas. Manufactured home parks in Santa Rosa and industrial districts in Petaluma face similar hot spots.

Ruomaldo Argota adjusts the cover on his parakeet cage as he and wife Marta Maria Farias stand near the front of their home, Wednesday, July 19, 2023 in Sonoma.

(Darryl Bush / For the Index-Tribune)

Communities located in heat islands often have to expend more electricity to employ air conditioning or fans to circulate heat. Because heat islands are often in low-income areas of a city, those residents are less likely to be able to afford the higher utility costs required to stay cool.

Farias said doesn’t want the air conditioning unit fixed, however, because of the toll on their electricity bill — money her family cannot afford to spend.

Marta, Ruomaldo, their grandchild and the rest of their family live in Boyes Hot Springs in Sonoma Valley, which has some of the most overcrowded households of any neighborhood in Sonoma County, according to a 2022 State of Housing report by the nonprofit Generaton Housing.

(Chase Hunter/Index-Tribune)

Two sides of the Valley

On Sonoma Mountain, Glen Ellen and the east side of Sonoma, classic farmhouses ubiquitous with the established families and new money transplants are flush with bushes of peonies and tulips and roses. The residents here have some of the longest life expectancy and nearly the highest quality of life found anywhere in Sonoma County, according to a Portrait Sonoma.

Yet just two miles away in Boyes Hot Springs, employees of the wine, tourism and hospitality industries reside in homes without air conditioning, with fewer trees and face one of the lowest qualities of life found anywhere in Sonoma County.

“When all these disasters and the pandemic came along, it made it very difficult to survive so we just have to really live off with the bare minimum while still having to pay high rent,” Farias said. “Everything’s gotten tougher the past five years.”