Do penalties reduce medical errors?

This report was produced as a project for the 2015 California Data Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

California has issued $17 million in fines for severe yet preventable medical errors since 2007, publicly shaming 192 hospitals for everything from leaving surgical sponges inside patients to giving fatal doses of medication.

News releases about the mistakes have ensured that they receive plenty of consumer attention through news outlets, blogs and social media.

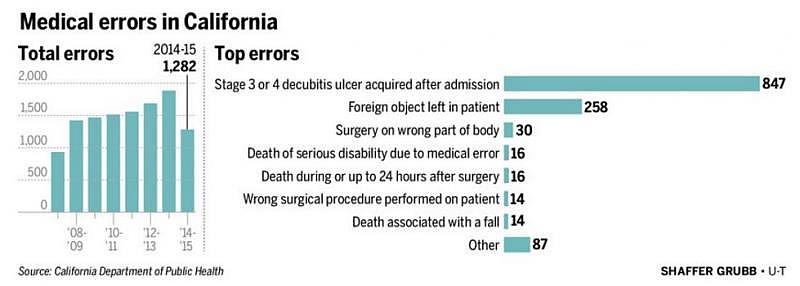

But the state’s penalty system, the only one of its kind in the United States, has failed to bring about a significant reduction in such incidents, according to an analysis of state data by The San Diego Union-Tribune. In fact, even after marked improvement between 2014 and last year, the number of errors is still higher than when California’s program began nine years ago.

While Medicare punishes hospitals by not paying for treatment linked to medical errors and a few states fine hospitals for each day they do not report certain mistakes, California is the lone state that routinely publicizes and issues penalties for a specific list of errors that can cause “serious injury or death of a patient” whether or not those blunders were reported promptly.

The mistakes are known as “immediate jeopardy incidents,” according to the state Department of Public Health.

Although these severe missteps are rare — less than 1 percent of all hospital patient discharges in California involve them — patient advocates, insurance companies and leaders of medical organizations have long called for their rates to plummet. The groups note that this category is just the nucleus of a wider circle of errors committed by physicians, nurses, technicians and others.

In the end, each of the 11,749 errors reported to California regulators from 2007 until March 2016 was avoidable, said Lisa McGiffert, director of the Safe Patient Project at Consumers Union, the advocacy arm of Consumer Reports.

“Yes, the numbers are small when you think about the total number of procedures that hospitals perform, but every one of these numbers is a real person who died or was seriously disabled because of some event that could have been prevented. The goal has got to be getting to zero,” McGiffert said.

The state agency in charge of issuing penalties for such errors would not discuss its program despite several months of requests for comment. The Department of Public Health not only refused to provide an official for an interview on the subject, but also gave incomplete and incorrect data for this story.

Experts said minimizing hospital errors is a complex goal, but not an impossible one. After all, some efforts to curtail preventable medical harm have shown progress.

For example, projects to reduce hospital-acquired infections — from pneumonia to bloodstream infections — have achieved clear success. Between 2008 and 2014, hospitals nationwide reported an average drop of 50 percent in blood infections associated with central line catheters used to deliver medications, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

In addition, a federal study published last year said there was a 17 percent drop in errors between 2010 and 2014 among a sampling of Medicare patients. And California’s latest statistics on severe bedsores, another avoidable condition, indicated improvement.

But other types of errors, such as foreign objects left inside patients during surgeries, have continued to increase.

This trend comes even as hospitals reinvent themselves with safety in mind. Health care has turned to other high-risk industries such as nuclear power and aviation for ideas, and the result has been more layers of safety checks before surgeries, bedside bar-code scanners to help prevent medication errors and even wireless sponge-tracking systems.

While high-tech solutions often get the most attention, experts said changing the health-care culture in relation to errors is the most important change needed to make sustainable progress in reducing the number of rare but deadly errors as close to zero as possible. They agree that it won’t happen until everyone, from nurses to janitors, feels comfortable speaking up when they see a problem in the offing.

The other big issue concerns how medical errors are reported and counted.

Reporting requirements

No federal law forces hospitals to report their medical errors, and only 27 states require them to do so. Each state decides which types of mistakes hospitals must report, making it difficult to compare data across the nation.

Even states that mandate reporting are known to have inaccurate data. For instance, a 2012 report from the U.S. Office of Inspector General found that those states’ systems captured only 12 percent of total errors after examining a sampling of nearly 800 Medicare patients’ records.

This reality puts an asterisk next to the numbers in state reports on medical mistakes.

The 1,283 adverse events tallied in California’s fiscal 2015 report look low compared with national studies estimating that errors account for 200,000 to 400,000 deaths each year. Given that California has about 10 percent of the nation’s population, it could stand to reason that the state has 10 percent of the fatal errors. That would be 20,000 to 40,000 — far larger than what ends up getting reported.

Some of the holes in reporting requirements are well-known. For example, severe hospital-acquired infections are not included in statewide totals. The same is true for errors that are misidentified and categorized as something else. Misdiagnosis, cases where doctors diagnose and treat the wrong disease or medical condition, are also known to be underrepresented by error-reporting systems.

Since 2007, California has tracked 27 significant types of patient harm, from operating on the wrong body part to sexually assaulting patients. While the program does not capture the full scope of errors, it is nonetheless a consistent picture of the most serious kinds of harm that can happen to patients.

Penalty patterns

To date, California has issued 354 administrative penalties to 192 of the state’s 495 general and psychiatric hospitals. More than half of the facilities in the state have not received a single citation, while others have received several.

Seventeen-year-old Elord Revolte was beaten to death in 2015 at the Miami lockup. Some youths said his beating was orchestrated by an officer, who was indicted last April.

The highest number recorded so far is 13 penalties that have been levied against Riverside County-based Southwest Healthcare System and the pair of hospitals it operates in Murrieta and Wildomar. UC San Francisco Medical Center is second with nine fines.

The penalties run from $75,000 to $125,000 per incident.

While it is tempting to think that hospitals with the most penalties have the lowest quality, a deeper examination shows that is probably not the case.

California’s Office of Statewide Health Planning conducts an annual analysis of health care data that takes into account the sickness of the patients each hospital serves, ranking each facility in the state better, the same or worse in 12 different patient mortality categories from aortic aneurysm to stroke.

Statewide, about 5 percent ranked better than their peers in at least one category, 2 percent ranked worse and 93 percent were rated no different than average.

Statistics from 2014, the most recent year on record, show that it was the same breakdown for the 192 hospitals that have received at least one immediate jeopardy penalty from the state.

It means that while the hospitals have reported at least one deadly mistake, their overall mortality rates generally do not differ from those of all hospitals in California.

‘Dumb’ mistakes

This distinction makes sense to Dr. Robert Wachter, chief of the division of hospital medicine at UC San Francisco.

He said the industry has had a tight focus on error prevention since the Institute of Medicine published its seminal report “To Err is Human” in 1999.

The addition of Medicare penalties and Affordable Care Act sanctions have meant that no modern hospital has been able to ignore mistake prevention. All of these factors, he said, have changed the nature of the errors that do slip through.

“Periodically, you’ll see errors where you think, ‘Boy, even the basic blocking and tackling was not there. They’re just not doing it.’ But that’s extremely rare. We certainly have not fixed the problem, but the kind of dumb stuff we used to see, those really don’t happen anymore,” Wachter said.

Rachel Jokela, director of the Adverse Events Program at the Minnesota Department of Health, said she has noticed a gradual change in the nature of adverse events. The state was one of the first in the nation to mandate event reporting and Jokela’s department has been monitoring events since 2004.

She cited the retention of foreign objects as an example.

“Back when our reporting system started, we would see things like large retractors lost in the body during surgery. We don’t see that anymore. Now what we see are these 14-millimeter microneedles that can’t necessarily even be visualized on X-ray. The count of events may not have changed dramatically, but the type of event is changing,” Jokela said.

Still, substituting retractors for needles is no kind of long-term solution.

Everyone acknowledges that the goal is getting to zero. What’s not clear is whether penalties are the best way to reach that goal.

Transparency

California is alone in issuing penalties and news releases for immediate jeopardy errors, but the results are similar to Minnesota, which does not have a penalty program. In 2008, Minnesota’s total number of reported adverse events was 312. By 2015, that number dropped to 276, though new mandatory reporting conditions that took effect in 2014 has pushed the number past the 300 mark again.

Jokela said she has monitored California’s experience with penalties but said her state doesn’t plan to take a similar route.

“Since there hasn’t really been a great improvement in the rates in California, no one has pushed for fines to be looked at legislatively,” Jokela said.

She said many in the industry feel that penalties could make facilities less likely to be open about the mistakes that occur.

Dr. Helen Burstin, chief scientific officer for The National Quality Forum, thinks along those same lines.

“We want more reporting of events. We want to understand what’s happening. People need to feel empowered to come forward and share what happened because it is through that transparency that we can make progress,” Burstin said.

When she talks about transparency, the most severe errors are only part of the picture. The deadliest mistakes are usually preceded by many smaller errors. Every time a patient dies from receiving an improper dose of medication, for example, that death was undoubtedly preceded by other instances of medication mismanagement.

The idea is to create a collegial culture where smaller errors are freely reported and shared, even celebrated, Burstin said. That, in the long run, is how hospitals get close to zero.

“While we ultimately want to reduce all patient harm, it’s critical that we have the opportunity to have a culture of safety that allows us to have full reporting and sharing so that the health care system can learn,” she said.

The big picture

In California, there does appear to be more sharing and reporting going on. The number of entity-reported events increased from 6,901 in 2013 to 7,283 in fiscal 2015, according to state reports. The state also investigates more than 3,000 public complaints each year.

But few of these have turned into fines and bad publicity. Inspectors have a complicated set of rules in deciding which infractions rise to the level of putting a patient in “immediate jeopardy.”

In the most recent fiscal year, there were only 28 administrative penalties and 139 lower-level fines for failure to report errors out of 1,283 adverse events reported statewide.

To precisely determine whether California’s penalty system is making headway against medical errors, it would be useful to see whether frequently fined hospitals have managed to lower their overall rates of mistakes.

The California Department of Public Health provided a listing of more than 9,000 error-involved incidents statewide, but the list appears to be incomplete and has wrong data in some places, making it difficult for the public to measure whether the overall number of mistakes decreases after hospitals are penalized.

This lack of clarity causes some, like attorney Mark Kadzielski, a partner in the firm Pepper Hamilton, to question whether the millions that hospitals have paid in fines during the past nine years would have been better spent at the facilities where errors occur.

“The only thing the penalties have done, very clearly, is generate a lot of revenue for (the public health department). Instead of a $100,000 fine, why couldn’t they tell hospitals to use that money to go out and hire a quality nurse or make some other improvement that is directly related to the error that occurred?” Kadzielski said.

The agency did not respond to questions about this or related issues.

Some health providers said the state’s penalty program has had positive effects.

Wachter, the safety expert from UC San Francisco, said even though the system seems to punish hospitals like his that are conscientious about reporting mistakes, it has brought greater awareness to the issue.

“I think it does change the way a hospital’s board and CEO think about safety and the investments they’re willing to make to prevent errors,” Wachter said.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

*As a patient, you can take some steps to lessen your chances of becoming the victim of a medical error in the hospital. These actions include:

*Inquiring about better alternatives to the procedure you’ve been recommended. Visit choosingwisely.org for information about which treatments may be unnecessary.

*Choosing a hospital, whenever possible, that performs a high volume of the procedure you need to undergo. Studies show such places and physicians tend to have better outcomes for that procedure.

*Verifying that your vaccinations are up to date before you’re admitted to the hospital.

*Telling your doctor, nurse, pharmacist and anyone else involved in your care about what medications you’re taking. Arrive at the hospital with your full list of drugs and be honest about any other self-medication. That includes dietary supplements, vitamins, herbs and recreational drugs.

*Listing any medications you shouldn’t take because of reasons such as allergic reactions or other known adverse outcomes.

*Making sure all medicines you receive in the hospital — including through syringes, tubes, bags and pill bottles — have labels. Don’t be afraid to read these labels to see if they match what your physician prescribed.

*Asking caregivers to wash their hands before they tend to you — if they haven’t done so. Unwashed hands are a main way of spreading infection in hospitals.

*Finding out whether your surgeon uses a checklist for your operation. Research shows that such checklists, even simple ones that include steps for preventing infection, can significantly lessen the error rate.

*Confirming with nurses, imaging technicians, anesthesiologists and your doctor that they have correctly identified the part of your body targeted for a procedure. For example, all of your caregivers should agree on which kidney, knee or arm is slated for surgery. One common step is for the surgeon to sign his/her name on the area targeted for surgery.

*Requesting an update each day on when your central-line or urinary catheter can be removed. Studies show that catheters, a prime source of infection, are often left in place long after they’re no longer needed.

*Going over all medication instructions before leaving the hospital.

*Asking as many questions as you need. If you don’t understand something your caregivers are about to do, speak up. Doctors, nurses and others should take action based on your consent.

[This story was originally published by The San Diego Union-Tribune.]