Fear of Family Separation a Barrier to Addiction Care During Pregnancy

The story was originally published by MedPage Today with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s Data Fellowship.

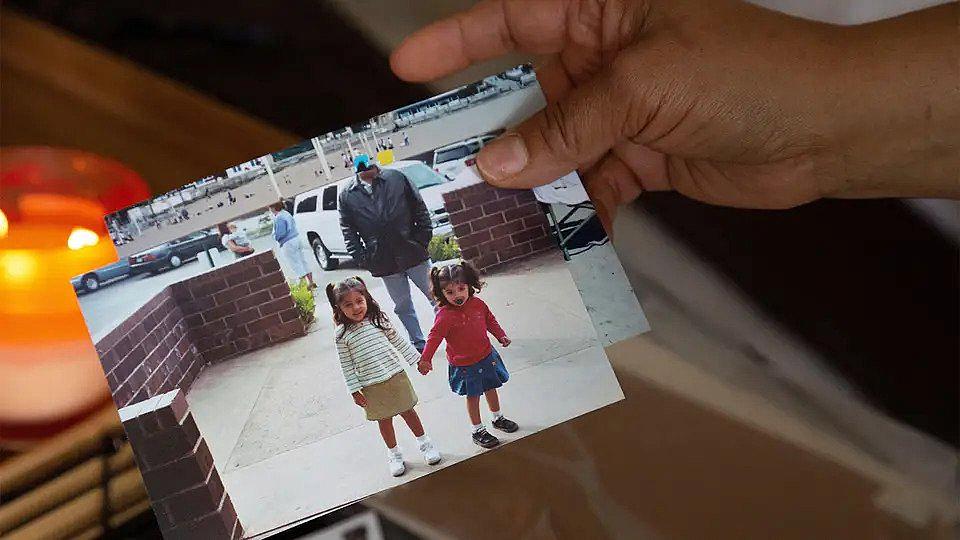

Lauren thought she would be able to stop using drugs when she got pregnant.

She had picked up and moved from Arizona to Oklahoma City in 1989. Lauren, whose name has been changed to protect her privacy, had a son at home and a baby on the way, and had been using cocaine for the past 4 years.

When Lauren found out she was expecting, she wasted no time before getting an appointment with the ob/gyn to make sure that her pregnancy was going smoothly. But when her doctor asked her about her medical history, she didn't offer up information about her struggles with addiction.

"I never did tell her that I was addicted or that I was using," Lauren said. "I was ashamed that I couldn't stop."

Lauren said that fear, guilt, and shame kept her from disclosing to her doctor that she was addicted to cocaine. If she told her doctor that she was using for the majority of her pregnancy, she wasn't sure what would happen next.

"Would they take my baby away? I didn't know," Lauren said.

To this day, pregnant women with substance use disorder (SUD) still fear that getting treatment will result in child removal. Many who struggle with addiction during pregnancy hide their substance use because they are afraid that medical providers will report them to state child welfare agencies, preventing them from getting the care they need, patients, experts, and advocates told MedPage Today.

Drug testing practices and mandatory reporting rules can often lead healthcare providers to make unnecessary reports to child welfare agencies, experts said. Although healthcare professionals in New York are not mandated to report pregnant patients with a positive drug test to the family regulation system, confusion around reporting requirements and biases about people who use drugs may result in unnecessary child removals.

"There's been an epidemic of child welfare reports -- in particular, foster care placements -- driven by the opioid crisis in the past few decades," said Mishka Terplan, MD, MPH, an ob/gyn and addiction medicine specialist based in Maryland. "Many of these reports are actually in excess, and beyond what is legally required."

The war on drugs in the 1980s and 1990s fueled thousands of family separations that disproportionately affected the Black community and other minority groups. Media reports and medical studies perpetuated narratives based on shoddy science about the harms to babies exposed to crack cocaine, leading to stigma and over-policing of mothers who used drugs in marginalized communities.

While the precedent was set in the '80s and '90s, the onset of the opioid crisis has led to greater attention around rates of foster placements across the country.

In New York City, there were nearly 44,000 reports of child abuse and neglect in 2021, impacting about 69,000 children. A third of those reports had credible evidence of child abuse and neglect, the data show.

One in four removals of children from their parents' care involved an allegation of substance use, according to 2017 data obtained via an information request from the advocacy organization Movement for Family Power.

Medical organizations and advocates say that the excess in child welfare reports involving families who struggle with addiction is caused by overreporting of positive drug tests. Many have called for informed consent in drug testing, ensuring that patients understand the potential consequences of a positive test.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has called routine urine drug screening "controversial," recommending in a policy statement that tests only be performed with patients' consent. The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) also advocated strongly against "the punitive approach taken to substance use and SUD during and after pregnancy," in a policy statement released last year.

Punitive approaches to substance use in pregnancy, such as requiring providers to report their patients or equating substance use with child neglect, can bar patients from accessing basic obstetric care, research shows. Mothers in states with punitive policies for substance use in pregnancy received worse obstetric care, including later receipt of prenatal care and lower odds of a postpartum health appointment, according to a study in JAMA Pediatricsopens in a new tab or window.

Despite calls from medical groups to obtain informed consent before drug testing pregnant patients, testing without consent still happens. A woman who delivered at Brookdale Hospital in Brooklyn recently sued the hospital for drug testing her without consent.

"When you ask, why would a person be fearful of accessing the most fundamental piece of healthy pregnancies -- prenatal care -- it's because they're faced with two very difficult decisions," said Miriam Mack, JD, policy director at the Bronx Defenders family defense practice in New York.

"You either risk not having a healthy pregnancy, you risk your life, you risk the development of your fetus," Mack said. "Or you get prenatal care, and you risk that baby being ripped away from you."

While a positive toxicology screening alone does not merit a report to child protective services (CPS) in New York, there still may be confusion among providers. Fears that they will lose their license or cause harm creates a culture of reporting to be safe rather than sorry, advocates say.

Mandatory reporters are required under the the federal Child Abuse and Prevention Act (CAPTA), a 1974 law that guides states on how to prevent and investigate child abuse and neglect. The law mandates states to meet certain reporting requirements to get funds for child welfare agencies.

CAPTA requires states to establish treatment plans for infants who are affected by substance use or withdrawal symptoms, known as "plans of safe care." But the federal law does not define what a newborn who is affected by SUD is, according to ASAM. This leaves it to states to define what requires a report to child welfare services.

"The way [healthcare providers] are trained on mandated reporting is so vague," said Joyce McMillan, founder and executive director of JMAC for Families, a non-profit in New York City that advocates for families with cases in the Administration for Children's Services.

"Even if a patient, say a pregnant or birthing patient, tests positive for a substance, there is supposed to be an assessment of safety and risk for that patient and the baby before reporting," said Morgan Hill, director of the Healthy Mothers Healthy Babies program at Bronx Defenders. "We know that that does not happen most of the time, unfortunately."

Child welfare involvement disproportionately affects people of color, drawing attention to biases in the reporting process. Nationwide, Black children are reported to child welfare agencies at twice the rate of white children. Once reported, cases involving Black children are more likely to be investigated, taken to court, and result in a child's removal from the household, according to an article published in Pediatrics.

"Multiple points in this process are subject to bias, but the process begins with reporting," the article says.

Racial disparities in child welfare reports and calls to end overreporting of substance use to state agencies have led some New York hospitals to change their practices around drug testing.

NYC Health + Hospitals, the public hospital system in the city, ended its practice of testing pregnant patients without written consent in 2020. The policy change followed an investigation by New York City's Commission on Human Rights into three private health systems, after advocacy organizations alleged that the systems' drug testing practices among pregnant patients discriminated against people who were Black or Latinx.

New York State has legislation in the works that would make it illegal for health systems to drug test a patient or their baby without written consent, in an attempt to provide patients with information about consequences of a positive drug test. This year marks the third legislative cycle that the bill will be introduced.

McMillan, who had her children taken out of her care in 1999 over reports that she used an illicit substance, said that drug tests shouldn't be used to penalize families or make a determination about one's ability to care for their children, but rather to guide medical practice.

"A drug test is not a parenting test," McMillan said.

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.