Fighting for care in Florida's Medicaid system (Part 2)

Maggie Clark reported this story with the support of the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism and the National Health Journalism Fellowship, programs of USC Annenberg’s Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Medicaid in Florida: 2 million kids. $24 billion battle.

An impossible choice: Doctors torn between patients and Florida's Medicaid system

2 Million Kids' series spurs support and quest for more data

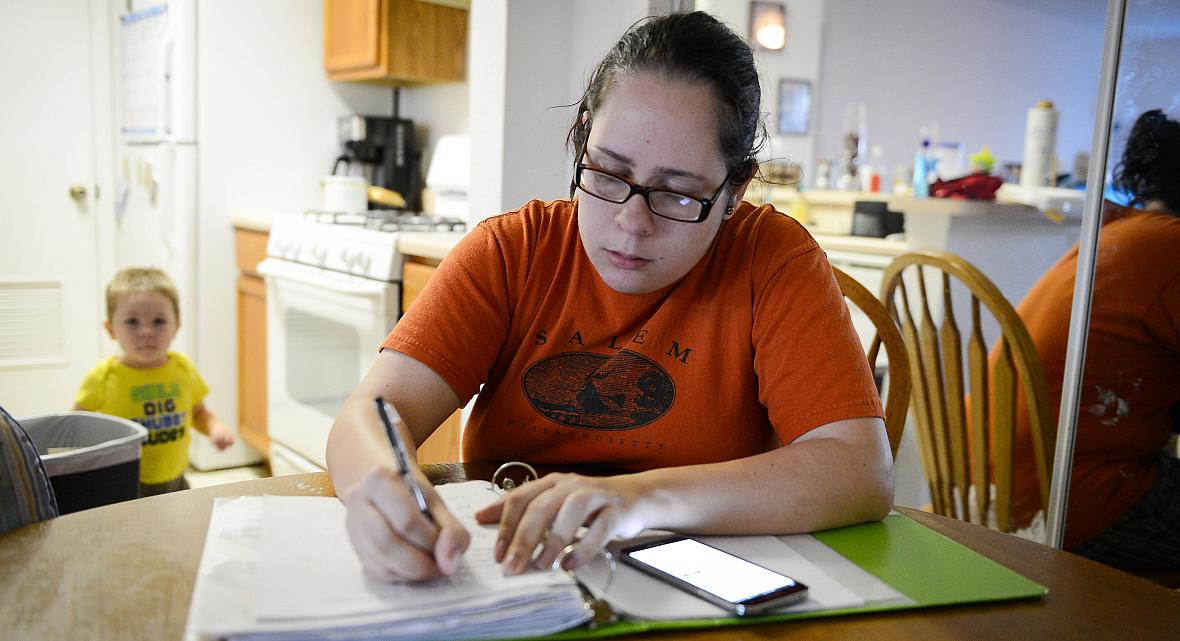

Jennifer tries to pay bills and go through some paperwork while her son, David, 2, competes for her attention. STAFF PHOTO / RACHEL S. O'HARA

Jennifer tried to calm herself as she balanced her 2-year-old son on her hip and walked toward her car in the parking lot of the doctor’s office. She packed David into his car seat, buckled her own seat belt and burst into tears.

Just getting in to see this child psychologist was a chore, as none of the specialists near her Leesburg home accepted Medicaid. That meant waiting three months for the appointment, begging her manager to give her the day off from her job at a fast-food restaurant and driving 50 miles to the Orlando office — only to have the doctor spend five minutes with her son, ignore her concerns and tell her to go someplace else.

The 20-year-old had hoped this time would be different. From the minute she enrolled her two sons in Medicaid, she says, it has been one slight after the next. From rude comments in the local clinic to being publicly embarrassed at the pharmacy to more tangible setbacks, such as being billed for a procedure that was supposed to be covered, Jennifer finds herself in a constant uphill battle to wade through the Medicaid bureaucracy and get decent health care for her children.

She is not alone.

There are 2 million children covered by Medicaid in Florida, and the care they receive is separate, unequal and substandard to the care received by children covered by private insurance, a federal judge affirmed.

They miss out on well-child checkups. They face a scarcity of pediatric specialists willing to treat them, must travel distances for doctor’s visits and face long wait times. There is an overall lack of dental care. Those problems “infect” every part of the program, Judge Adalberto Jordan asserted a year ago in his conclusions in a 10-year-old lawsuit against the Medicaid program.

Jordan’s findings validated what parents who rely on Medicaid for their children’s health care have been saying for years.

In doctor’s offices and living rooms across the state, low-income families on Medicaid are struggling to pay bills and keep food on the table. Navigating a health care system that treats recipients like second-class citizens can make an already-overwhelmed parent feel like a failure.

From minor hiccups in coverage to denials for lifesaving treatment, parents say they face a David-and-Goliath-like struggle in getting care for their children. And even when they get them in to see a doctor, they often face indifference from the medical provider.

Even before she went into the psychologist’s office in Orlando, experience had taught Jennifer, who asked that her last name not be used, to steel herself for what was about to come.

“I’m constantly wondering if my son is going to be treated as the cute and adorable kid he is, or if he’ll be treated like a case file,” Jennifer said.

It’s not all in her head. More than one-third of all Florida doctors do not accept Medicaid patients, and many pediatric specialists keep separate waiting lists for Medicaid recipients.

There is no legal requirement that doctors accept Medicaid patients, and increasingly, the physicians that do welcome them do so out of altruism, knowing they will likely lose money on these cases.

Florida’s reimbursement rates for Medicaid visits are less than half of the amount paid to doctors who treat seniors enrolled in Medicare.

“Trying to get specialists to see my patients, even within a 50 or 60-mile radius of the patient’s homes, is a nightmare,” said Dr. Ella Guastavino, an Englewood pediatrician with a practice made up mostly of Medicaid patients.

None of the local specialists in Englewood take Medicaid, Guastavino said, so she sends her patients a one hour-drive to St. Petersburg or Fort Myers, even for blood work.

“The specialists can get three times more money for seeing a patient with private insurance,” Guastavino said. “The specialists are available locally, but they won’t take Medicaid.”

Only 62 percent of Florida physicians were accepting new Medicaid patients in 2015, according to a physician survey conducted by the Florida Department of Health. The top reason doctors cited for not participating in Medicaid was low reimbursement rates.

In April 2015, after Judge Jordan’s finding that Florida violated federal Medicaid law, 22 Florida pediatric providers testified that their Medicaid patients are treated less well than their privately insured ones.

Dr. Shannon Fox-Levine, a pediatrician in Palm Beach, described how the pediatric ear, nose and throat specialist in her same hospital complex has a separate waiting list for Medicaid patients. When she refers a Medicaid patient, they wait up to three months or more, while patients with private insurance can get an appointment within two weeks.

Orlando orthopedist Dr. Jonathan Phillips described treating Medicaid patients with broken bones who spent weeks searching for someone to cast them. By the time they reached Phillips, he had to re-break and re-set their bones.

Even when parents find a provider for their children, it’s not a guarantee that they’ll be able to see the doctor. Dr. Patricia Blanco, who owns University Pediatrics in Sarasota, said that parents often bring their Medicaid-enrolled children to the office, only to learn that their insurance coverage has been switched without warning to a plan the doctor does not accept.

Switching is more common—and even more disruptive—for children in foster care, Blanco said.

One of Blanco’s special needs patients in foster care was bounced between two insurance companies over six months. That caused the patient to miss more than 20 appointments and wait four months for surgery with an ear, nose and throat physician.

Phoebe, a Sarasota mother who asked that her last name not be used, recently got a letter saying that her youngest son had been switched to a new Medicaid insurance plan without her knowledge. She was so shocked that she thought someone had stolen the toddler’s identity.

When she called the new company, they told her not to worry about it.

“I was still upset, but what can I do? I’d never heard of the switching happening before, and I never knew this could happen,” Phoebe said.

Doubts crept in. She wasn’t sure if she could even take her son to his previously scheduled checkup with his pediatrician, and didn’t know what papers or cards to bring with her.

Dr. Jose Jimenez, the owner of Small World Pediatrics in Wesley Chapel and president of the Hillsborough County Medical Association, said that he often hears the frustration of parents who don’t understand why they have to wait months for appointments with specialists who accept Medicaid, or why their child’s insurance company was switched without their knowledge.

“We do our best to educate the parents on the process, but even if you understand it, you can still feel frustrated if something in your child’s insurance changes,” Jimenez said. “They feel like they’ve lost control.”

§

Florida health officials acknowledge that parents of Medicaid-enrolled children face challenges.

In the rules governing Florida’s new statewide Medicaid managed care system, insurance companies must ensure that patients have access to appointments within a reasonable time and distance from their home, and have avenues to file complaints.

Administrators also translate every letter they send to parents into English, Spanish and Creole, and run the letters through a computer program to ensure that someone who reads at a fourth-grade level can comprehend the words used.

“Welcome to the Managed Medical Assistance (MMA) program,” a welcome letter for a newly eligible Medicaid enrollee reads. “The MMA program is a part of Statewide Medicaid Managed Care. In the Managed Medical Assistance program, you get to choose the MMA plan that is best for you. Follow steps 1-3 below to make a choice.”

The state Medicaid agencies contract with a customer service call center, known as the CHOICE counseling hotline, where trained assisters help families choose Medicaid managed care plans that best suit their health needs. And for families that feel their needs aren’t met, they operate a complaint hub, where anyone can fill out an online form detailing their problem, or call a number and make a complaint over the phone.

Their goal is to provide the highest quality of health care to the most people, said Florida Medicaid Director Justin Senior.

At the Medicaid call center, for instance, operators used to spend “ages” on the phone helping recipients, Senior said, “and I’m sure that the people that were served on those calls felt an enormous amount of love from the people that helped them.”

But a significant percentage of the people who called the help line never got through to a customer service representative, Senior said, so they have asked assisters to keep the calls shorter so that a greater number of people can get assistance.

“We’re starting to see in our satisfaction numbers that people are more satisfied overall than they were before,” Senior said. A recent survey of Medicaid patients found that more than 80 percent of parents would rate their child’s health plans at an 8, 9 or 10 on a scale of 0 to 10.

The health plans also offer members more options for care than the old Medicaid fee-for-service system. Plans offer transportation to appointments and a $25-per-month over-the-counter health products package, where parents can order the pricey essentials such as diapers, vitamins and Tylenol that can sometimes break a fragile family budget.

Information about these expanded benefits, however, has been slow to reach parents. State officials say they’re working to make sure that all members know the benefits available to them under the new system.

As a child, Jennifer heard her grandfather rail against the welfare state and call Medicaid recipients leeches, drug addicts and lazy.

She discovered that her family had been receiving Medicaid benefits for years when she became pregnant at 17 and Medicaid was the only insurance option for prenatal care for herself and her baby.

“I couldn’t believe it, because I’d been taught to believe that people who had Medicaid were lazy,” Jennifer said. “I work full time and so does my husband.”

Lazy would be the last word to describe Jennifer. She taught herself English by listening to Harry Potter books on tape after her family moved from Puerto Rico to Florida when she was in her teens. She got a job at the restaurant Bojangles Famous Chicken n’ Biscuits in Leesburg only to learn that she was allergic to the flour batter they used to fry up the chicken. Desperate for a paycheck, she kept the job anyway, managing as best she could by taking Benadryl and covering herself in lotion.

During late-night closing shifts, she bonded with other young parents struggling with Medicaid. But away from her friends, she doesn’t talk about her Medicaid status and faces slights when she tries to access care.

At her first prenatal appointment, the teenager sat down in the waiting room next to a woman who looked around the room, leaned over to Jennifer and commented, “How many babies in this room do you think Medicaid is paying for?”

She recently had a pharmacy clerk blurt out her insurance status in the Walmart pharmacy waiting area, and when Jennifer got upset and asked the clerk to keep her voice down, the clerk rolled her eyes and Jennifer was asked to leave. She had to get her medication at another pharmacy.

The slights and sneers do not just cause uncomfortable moments for Medicaid recipients. Studies show the constant feeling of being unwelcome can lead to health problems.

In a study of Medicaid recipients in Oregon, researchers found that patients are “sensitive to their low-income status” and that just a perception of prejudice based on insurance status may reduce the effectiveness of their medical care.

In more than 500 interviews with adult Medicaid recipients, researchers found, “how difficult it can be to engage with the health care system when you believe that the system might not want much to do with you.”

Medicaid patients felt unwelcome, the 2014 study published in The Milbank Quarterly reported, and as a result, many did not go back for follow-up visits.

Teresa Smith, a case manager and social worker at Sarasota Memorial Hospital, sees the effects of this stigma every day. It often falls to Smith to tell families facing large medical bills that they’re eligible for Medicaid.

In that moment, the reluctance to accept government help overtakes what should be a bit of good news.

“People are embarrassed that they have to be helped,” Smith said.

That feeling was especially palpable during the Great Recession, when newly poor families found themselves eligible for Medicaid, said Kim Samuelson, who helps families access insurance coverage at Golisano Children’s Hospital of Southwest Florida in Fort Myers.

From 2007 to 2012, about 1.2 million new members enrolled in Florida’s Medicaid program, compared to the previous five years, when only about 100,000 new people enrolled in coverage.

Those financially devastated families were often too humiliated to ask for help, Samuelson said.

“During the Recession, people were losing their homes and the middle class economy went down to nothing,” she said. “These were newly poor people and they were embarrassed to accept help. They felt like they’d failed their families.”

For many, Samuelson said, their pride wouldn’t let them take food stamps or cash assistance. But they reluctantly accepted Medicaid coverage, at least for their children. The parents knew an unexpected hospital visit could ruin them financially, and they were willing to swallow their pride if it meant caring for their kids.

Shame of “being on the dole” tends to stifle much public conversation about Medicaid. That stands in stark contrast to Medicare, the universal health care program for Americans age 65 and older, which is supported by an industry of aging services providers and political associations such as the AARP.

Medicaid patients often have to fend for themselves.

Because of the stigma and the confusion, parents like Jennifer often wish they could drop the Medicaid coverage altogether.

On a December morning, Jennifer goes through a practiced ritual to help her get through a call to her insurance company, and remember that her kids will say healthier and live longer if they stay covered.

She pulls out a green binder full of bills and insurance letters from the closet behind her kitchen table. The young mom wipes the breakfast crumbs off the table, sits down and thumbs through the pages while David watches his favorite cartoon a few feet away.

Staring at the phone in her hand, she gives herself a quiet pep talk, then begins to dial.

“You’re doing the best you can do for your children. It may not be what other parents can do, but you’re doing the best you can.”

[This story was originally published by the Sarasota Herald-Tribune.]

Photographs by Rachel S. O'Hara/Sarasota Herald-Tribune.