Forgotten Children: The Unseen Victims of Gun Violence Are the Children Left Behind

The story was originally published by Verite News and MindSiteNews with support from our 2024 National Fellowship.

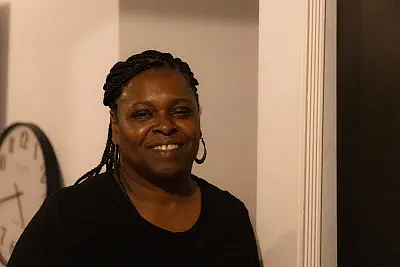

Erica Taylor, with four of the seven grandchildren she has been taking care of since her daughter was shot by her ex-partner in 2017, paralyzing her. All of the children witnessed the shooting.

Photo: John Gray, Verite News

This is the first part of Forgotten Children, a series on the tragic and underreported problem of childhood grief – and efforts to address it. Parental death has been rising in the U.S. due to COVID-19, the overdose epidemic and gun violence. MindSite News reported the story in collaboration with Verite News of New Orleans, which contributed photography and video, and is co-publishing.

It only takes one bullet to shatter the lives of eight children.

In the early morning hours of Sunday, Sept. 1, a fight spilled out of the Shamrock bar in the Mid-City neighborhood of New Orleans. Raven Francis, her sisters, and a friend had gone to the bar for a girls’ night out, and about a half-hour after the melee they piled into their car to leave. But danger followed them.

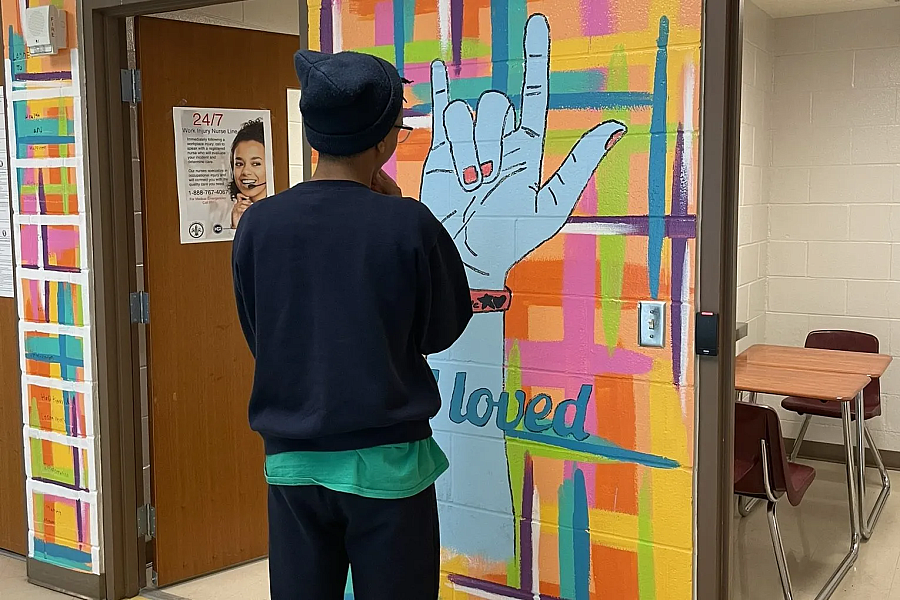

K., who has lost five friends and a cousin to gun violence and another cousin to tuberculosis, looks at a portion of a mural that says “feel loved” on the walls outside the visitation room at the Juvenile Justice Intervention Center.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

A witness told police that a gun-toting woman involved in the bar fight, Chante Mark, 24, had summoned a couple of male friends, who arrived in a black SUV. The SUV followed Francis’s vehicle as it left the parking lot, police say, and someone inside the SUV repeatedly fired at it. Francis was struck in the head and others in the vehicle were injured as it swerved into a fire hydrant and overturned. Francis, 29, was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Peace Ambassadors left a sign near the spot where Raven Francis died in a shooting, leaving behind four children.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Her grieving family described Francis in an online tribute as “loving, caring, outgoing, thoughtful, and most of all, a fantastic mother…family was everything to her.” The bullet that killed her also left her four children – ranging in age from 6 months to 10 years – without a mother. Mark’s four children effectively lost their mother to incarceration, at least temporarily, when she was arrested and jailed on charges of second-degree murder and aggravated battery. Her case is pending.

Gun violence in the U.S. is typically tracked by logging shooting incidents or victims or homicide arrests. But this tragedy reveals an overlooked casualty count: the grieving children left behind. Studies show that children bereaved after the death of a parent are at risk of long-term effects, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, and academic and behavioral problems. A child once outgoing and cheerful may withdraw, act out, or lose interest in school – often without teachers or administrators understanding why.

This unseen aftermath of loss was amplified by the pandemic, when parental deaths rose by 46% due in large part to COVID-19, gun violence, and opioid overdoses. It left a shadow epidemic of child grief. Even as COVID deaths subsided in 2022, the number of children nationally who experienced the death of a parent remained 32% higher than in 2019.

Across the country, bereaved children are disproportionately from lower-income communities of color, where parental and sibling loss is much more common than the national average. New Orleans treasures its close-knit neighborhoods, but it is also home to communities scarred by poverty, racism and entrenched disparities. In 2023, shootings occurred on average once a day and through November 2024, the city had logged an average of about 11 murders a month. No one knows exactly how many grieving children are left behind because there is no systematic way to identify the young survivors.

Danny Allen, who leads the Peace Ambassadors program of Ubuntu Village, doing community outreach in response to a shooting in New Orleans’ Garden District.

Photo: John Gray, Verite News

Yet there are estimates, and they reveal the toll. One in 10 Louisiana children will lose a parent by the time they turn 18, the fourth-highest rate in the U.S., according to state estimates by the JAG Institute, a research initiative of Judi’s House, a comprehensive grief center in suburban Denver. Children from the poorest families in Louisiana are 26% more likely to experience the death of a parent or sibling by age 18 than those in the state’s highest income group.

New Orleans is seeking to become a model for how to help those forgotten children. Through the health department’s Office of Violence Prevention, the city is building an “ecosystem” of mental health support for children as well as adults.

“Childhood bereavement has been an ongoing issue for many, many years, particularly in under-resourced communities where gun violence is more common,” said Julie Kaplow, a psychologist and expert in child trauma and grief. “I think COVID really brought to light that grief is real, that bereavement is happening, and it allowed us to start to have more dialogue and raise awareness around the fact that kids grieve, too.”

Julie Kaplow (left), director and founder of the Trauma and Grief Center at the Children’s Hospital of New Orleans, and Sarah Hinshaw, a social worker specialized in assessing and treating young children, talk in the center’s play therapy room.

Photo: Michele Cohen Maril

Kaplow is director and founder of the Trauma and Grief Center at the Children’s Hospital of New Orleans. She has spread grief support services to schools in Orleans Parish and neighboring Jefferson Parish in partnership with another Children’s Hospital program called ThriveKids, which is partly funded by the city of New Orleans through COVID-related American Rescue Plan Act funds.

Additionally, the city’s health department funds the Seeds of NOLA Trauma Recovery Center at University Medical Center, which provides trauma-informed mental health care to adolescents and adults who are survivors of traumatic injury and community violence – and to their loved ones. A $7 million, five-year grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention enabled Tulane University to create a youth violence prevention center. And the Children’s Bureau of New Orleans, originally founded as a child welfare agency in 1892, shifted its focus in the early 1990s to address the mental health needs of children and families struck by community violence and now embeds therapists in schools, after-school programs, and other youth-serving organizations.

Will this trauma support “ecosystem” be able to counteract the longstanding gaps in mental health services, especially for children living at or near poverty? Many barriers remain, including a lack of providers. The sustainability of funding is also uncertain. In November 2024, the New Orleans City Council approved almost $1 million to offset federal funding cuts in grants to aid crime victims – cuts that occurred, in part, because the police department was unable to comply with new rules for reporting crime data.

Even with the current funding, “the capacity issue citywide is real,” said Berre Burch, clinical director of the Children’s Bureau. “The needs far exceed what we have available.”

‘The loss of a world’

When Danny Allen learned of the Shamrock bar shooting, he went to the Francis home to offer help. Allen leads a team of Peace Ambassadors, a program of the New Orleans racial justice organization Ubuntu Village that supports families caught up in gun violence or the juvenile justice system and seeks to prevent retaliation. In the aftermath of shootings, they become a link to community resources and trauma therapy for survivors. After visiting the Francis family, Allen told MindSite News that the 10-year-old boy was “in disbelief and not really understanding what happened to his mother.”

But by the time a vigil was held for his mother two nights after the shooting, the boy had taken on the demeanor of a protective oldest son. As a local TV reporter interviewed him, only his camo-patterned slip-on sneakers and Nike socks were visible on camera, to give him anonymity. His voice sounded eerily calm even as he alternated between speaking about her as past and present: “I miss my mama a lot. She’s pretty funny. She was a nice person. She loved us very much. She’d do anything for us, and she will always be with me.”

Beneath those stoic words lies a troubling reality: The death of a parent is one of the most traumatic and stressful events that can happen to a child, and it carries lifelong consequences. Kids may have a range of reactions, from magical thinking and denial to anger or numbness. “It’s not only the loss of a parent; it’s the loss of a world,” said Irwin Sandler, a research professor of psychology at Arizona State University who focuses on bereavement and resilience.

Psychologist Tashel Bordere coined the term suffocated grief to describe the experience of Black youth whose normal grief reactions – distraction, withdrawal, angry outbursts – were punished by teachers or other adults rather than met with empathy and understanding.

If that loss is sudden, the ramifications are still deeper, whether the cause was suicide, an accident, a shooting, or an unexpected illness. For at least seven years after a parent’s sudden death, children have higher rates of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation, according to a University of Pittsburgh study of the “burden of bereavement.”

Deaths due to gun violence leave an aftermath of trauma and a sense of stigma. That was something psychologist Tashel Bordere noticed even when she was growing up in New Orleans. She began collecting obituaries, particularly of Black teenage boys, she told an NPR-affiliated station in 2020. “I was very curious about what kids were thinking when they got back to school,” she said. “I was just really curious about the notion that people were not really talking to these kids, talking to my peers and [me] about these violent losses that were occurring that are so complex and traumatic.”

Bordere became a thanatologist at the University of Missouri-Columbia – a specialist who studies death – and the board president of the National Alliance for Children’s Grief. She coined the term “suffocated grief” to describe the experience of Black youth whose normal grief reactions – distraction, withdrawal, angry outbursts – were punished by teachers or other adults rather than met with empathy and understanding.

The grief reaction

Grieving is a natural process, not a mental illness, but children need to process their grief in a supportive environment. As many as 10% of children develop prolonged grief disorder, with disabling, persistent symptoms. Kaplow and her research team have found that rates of prolonged grief disorder are much higher among youth who experience deaths due to violence. Other children may have lingering effects that are less severe.

Grief is a reaction to the love they have for the person. Our goal is not to get rid of the grief, but to give them tools to cope with the grief over time.

Julie Kaplow, Founder of the Trauma and Grief Center in New Orleans

Sandler began his research into child grief about 30 years ago with a central question: “Can we develop sound, strong, scientific evidence that we can make a difference” for grieving children? He developed the Family Bereavement Program with colleagues at Arizona State to provide parenting skills to the surviving parent or caregiver and coping and emotional regulation skills to help the children deal with their grief.

Through years of testing, they showed that the program reduces the risk of depression and emotional distress. A randomized trial followed children, adolescents, and parents after they went through the 12-week program. Fifteen years later, the children and teens who participated in the bereavement program were half as likely to have major depression as young adults, compared with matched children and teens who simply received educational books about grief.

In a similar approach, Kaplow developed Multidimensional Grief Therapy, a program for children that also is evidence-based and delivered in a group setting. For example, a facilitator gives examples of common responses to grief – from the girl who feels angry and guilty to the boy who wants to make something positive come from his loss.

“Grief is a reaction to the love they have for the person. So our goal is not to get rid of the grief, but to give them tools to cope with the grief over time,” said Kaplow, who is also executive vice president of trauma and grief programs and policy at the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute in Houston.

To make that support and individualized therapy more widely available, Kaplow has founded trauma and grief centers at children’s hospitals in New Orleans, Houston, and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It’s a model she hopes to be able to support elsewhere in the country. Those working in child grief support echo the wish for more resources.

“We know if we can provide them with the care that they need at the time that they have that loss, we can prevent so many future difficulties,” said Micki Burns, chief executive officer of Judi’s House, a grief center in Aurora, Colo.

Putting words to feelings

An inspirational mural painted on the walls at the Juvenile Justice Intervention Center in New Orleans.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

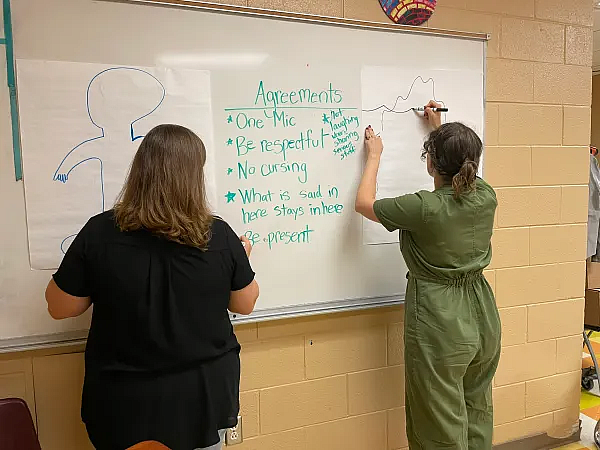

On a blustery fall day, when gusts blew the rain sideways into tiny wet daggers, two licensed clinical social workers prepared a classroom at the Juvenile Justice Intervention Center in New Orleans with tools to help incarcerated teens give voice to their feelings. Mary Chastain-Alford drew an outline of a body so the group could talk about the physicality of feelings: a broken heart, a tight fist, butterflies in the stomach.

Social workers Mary Chastain-Alford and Nell Okula write on a whiteboard in preparation for a grief group at the Juvenile Justice Intervention Center. They always include basic rules including, “Be respectful…Be present.”

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

At the weekly, 90-minute grief group, the teens will think up as many “feeling” words as they can and will act out feelings in charades. “Sometimes, if you can understand what feeling you’re experiencing, you can better manage that,” Alford says.

Eventually, they will open up about people they loved who are now gone. For most of them, this is the first time they have unpacked the layers of loss – friends, cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and for some, parents or other caregivers. The JJIC, as it is known, is a holding facility for New Orleans youth who are awaiting a court proceeding. Some of them will be tried as an adult for a serious crime. Just being here is a loss in itself.

“Almost every single one of our youth here have been impacted dramatically by grief and loss either through violent crime, COVID, abuse, and just families being torn apart,” said Lee Reisman, a licensed clinical social worker who is superintendent of Youth Supportive Services. “These are kids who were born not long after Katrina. And so I think there’s also some intrinsic separation anxiety – there’s just all sorts of complex issues that are impacting this group.”

Sixteen-year-old K. grew up in New Orleans’ Uptown neighborhood, a childhood he described as “not bad, not good.” While his parents tried to give him what he needed, he said, “I still got exposed to a lot of stuff I wasn’t supposed to see at a young age, but that’s just the way our lives go.” Kids like K. often witness drug use, crime, fights, guns. (MindSite News is not using his name or details about his pending case to protect his privacy as he awaits court proceedings.)

For K., the tally of losses began in 2020, when he was 12, with a string of deaths almost too numerous to list: a cousin who died of a drug overdose, a friend who died in a shooting, a friend shot when someone was playing with a gun and it went off. “I lost another friend in 2022, I’m just thinking about it,” he said, fidgeting at a small, round table in a closet-like visitation room with cinder-block walls. “A lot of stuff be happenin’. You just, you can’t even keep track.”

On the day in January 2024 when he went to the funeral of a cousin who died by suicide – also a case of gun violence – another cousin died from tuberculosis. (As in many extended families in New Orleans, K.’s ties with his cousins were as close as friends or siblings.)

(When) I was talking about my cousin who committed suicide, I almost cried.” But “nobody ever cries” in the grief group, he said. “That is how we was raised, they don’t want to cry. They ain’t gonna show emotions. They don’t want nobody to see them weak.

K, 16, a participant at a grief group for residents of the Juvenile Justice Intervention Center in New Orleans

With the string of pandemic-era deaths, K.’s life slid off the rails. Sometimes he felt angry, sometimes he withdrew and smoked weed. He never talked about the deaths. He agreed to join the grief group at the JJIC because he heard they had good snacks. “But then I started going, and I started to see that this could really help me cope, get the stuff off my chest,” he said.

In one grief group activity, teens decorate “Good Grief” boxes. He put a three, seven, and 10 on the sides – for the Third, Seventh, and Tenth wards of New Orleans where his friends died of gun violence. He wrote “Rest Glizz,” using the nickname of one of those friends.

The grief group helped him open up and think about the kind of life he wants to have, K. said. “(When) I was talking about my cousin who committed suicide, I almost cried.” But he couldn’t do it because “nobody ever cries” in the grief group, he said. “That is how we was raised, they don’t want to cry. They ain’t gonna show emotions. They don’t want nobody to see them weak.”

Yet even acknowledging their grief is powerful. Giving voice to it could be transformative. One goal of the grief groups, says Alford, is “making the unspeakable spoken.”

Reisman hopes the grief support groups give some of the youth a step toward a different future. “The trauma that they’ve experienced cannot be resolved in eight to 10 weeks” of grief support, she said. “I think it is a door to open an opportunity and a new path to healing that some have not previously been exposed to.”

‘Solutions not shootings’

The last weekend in May of 2022 was a particularly bloody one in New Orleans: nine shootings, four killed, 11 injured. The headlines were quickly eclipsed by news of yet other shootings. In 2022, New Orleans had the nation’s highest homicide rate; amid a pandemic-era surge in violent crime nationally, the city had a spate of killings not seen since the mid-1990s.

On May 24, a very different shooting shook the nation, bringing a sense of collective grief and outrage as an 18-year-old killed 19 children and two teachers and wounded 17 others at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas.

There is no way to measure the relative weight of pain. But Ernest Johnson, founder of Ubuntu Village, worries about how society dispenses compassion – particularly when the traumatized children live in poor neighborhoods where gun violence is accepted as ordinary. “One of the things I think we always have to be careful about (is) not normalizing this, that these children should just accept the loss and that this is just what happens in society,” he said.

Ubuntu is a Zulu word that roughly translates to “I am because we are.” The organization seeks to rally communities to turn to “solutions not shootings,” as it says on Ubuntu yard signs. In the days after Raven Francis’s death, a yard sign marked the corner near where her vehicle overturned.

Ernest Johnson (left) and Danny Allen in front of a community mural outside the Ubuntu Village office at New Orleans’ Broadmoor Community Church.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Ubuntu Village works with Tulane’s Violence Prevention Institute and the Seeds of NOLA Trauma Recovery Center to support young people who have experienced gun violence, with the aim of disrupting a cycle of retaliation. Survivors are also often referred to Silence Is Violence, a community-based organization that provides resources, including counseling.

Julia Fleckman, the Tulane institute’s director of research and evaluation, is gathering data to show the effectiveness of the violence prevention work – in hopes that government funding will continue to support trauma-informed prevention programs even when the COVID relief money expires on December 31, 2026.

Building the capacity for prevention and trauma-informed treatment for youth, families, and communities takes time, but it is essential, she said. “Imagine not feeling safe over and over and over again,” she said. “That does something to a person that I think it’s hard to recover from.”

Aftermath of a shooting

Erica Taylor tells the story of how she worked to put her seven broken grandchildren back together after a horrific trauma. Getting them into long-term therapy was the key, she said.

On August 20, 2017, her daughter, Kenyetta Taylor, then 31, had just come home from work and was holding her six-month-old baby when her abusive ex-partner broke into the house. The children were all in the room and watched in horror as he fired a shot behind her ear, execution-style. The oldest child, who was only 10, followed instructions from the 911 dispatcher to put pressure on the wound.

When the EMTs arrived, all the children were covered in their mother’s blood. After surgery and eight months in the hospital, Kenyetta miraculously survived, though she was grievously injured. She suffered seizures that led to partial paralysis, and she remains bedbound.

On that first night, while Erica Taylor sat vigil at the hospital, her sister showed her images via FaceTime of her grandchildren thrashing in their beds. One sleepwalking boy seemed to be reenacting the aftermath of the shooting as he knelt on the ground calling out, “Mama! Mama!”

Grandmother Erica Taylor.

Photo: John Gray, Verite News

Taylor immediately began looking for the name of a therapist. She initially drove the children to appointments at the New Orleans Children’s Advocacy Center, which focused primarily on cases of child abuse, but for years the children have met with therapists at school, including through the Children’s Bureau program.

In the early days, the children could barely function. Terrified, they all wanted to sleep with her; she let them squeeze together however they could fit in the bed. They had nightmares and barely ate. They would be eerily quiet, but at other times burst into tantrums or fits of anger. Gradually, with her steady love and attention, they learned to calm themselves.

“I take it day by day with them,” said Taylor, “because if you think everything be going well, then boom, a situation will arise.”

Erica Taylor cuddles with three of her granddaughters as they look at vacation photos on her cellphone.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Kenyetta is able to talk and still hopes one day to walk again. The children wander into the room where she lies in bed watching TV, and they talk to her or hug her. But Erica Taylor is the one who orchestrates the controlled chaos of the household: snacks and an early dinner after school, homework, bath, bedtime. And the occasional movie night, when she prepares bowls of popcorn and cuddles with them on an extra-long sofa.

Before the shooting, Erica had two jobs and was saving money to buy a house. She quit the jobs and spent the money on the children and on medical equipment for Kenyetta that wasn’t covered by Medicaid. Through therapy of her own, she learned some strategies: When they’re going through a tough time, she tells them to draw a picture of how they feel, and then to draw another picture with a solution that could make those feelings better.

Their symptoms have slowly eased and she sees them excelling at school. She has worked to steer them from risky behavior; six of Kenyetta’s seven children are boys. The oldest grandson turned 18 this year and just started college.

“I would rather stop all the things I was doing in my life to make sure they have a life, because they are our future,” she said, as three granddaughters scrambled into her lap to look at old vacation photos on her phone (including two grandchildren from her youngest daughter). “Believe it or not, they are our future. These are the little people that’s going to be running this world when we’re older.”