On the front lines of the fight against Type 2 diabetes

This story was produced as part of a project for the 2016 California Fellowship, a program of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism's Center for Health Journalism. This is the second of two stories on Type 2 diabetes. Part 1 profiles a family struggling with diabetes that struck three generations.

A weekly farmers market in front of Children's Hospital Los Angeles gives patients, family and staff access to healthy food.

Dr. Steve Mittelman inspects the fresh fruits and vegetables at a farmers market on the grounds of Children's Hospital Los Angeles. He established the weekly market two years ago in his role as director of the hospital's Diabetes and Obesity Program.

"You really want the good healthy foods to be convenient and you’re not always going to think about going to the store to pick up these things," he says. "But if it’s right here at your work or where your child is, then you can pick it up very conveniently."

The market is also designed to help patient families living in areas "that don’t have access to fresh produce," Mittelman says. "Showing them what there is and what to do with it is an educational thing and an opportunity they may not have."

The farmers market is just one of a number of efforts by the medical and public health communities to combat the rise of Type 2 diabetes, especially among kids and young adults. Experts believe they won't get the upper hand on the disease until they persuade enough people that a healthy diet and regular exercise can prevent it or minimize its damage if it has already struck.

Type 2 diabetes occurs when the body’s insulin stops working or does not properly direct blood sugar where it needs to go. If left uncontrolled, the disease can lead to kidney failure, nerve damage, blindness, stroke and heart attack.

Type 2 disproportionately affects Latinos, African-Americans and Native Americans, and it has spread along with obesity. Latinos and Native Americans, or any group with indigenous heritage, have an slightly higher risk because of a genetic predisposition for diabetes, experts say.

In California, about 9 percent of adults have been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, and an estimated 46 percent are prediabetic or undiagnosed, according to a recent study by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. In Los Angeles County, the figures are 10 and 44 percent, respectively.

Most worrisome to doctors is the number of kids and young adults being diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes in recent years. It's happening so often that Type 2 is no longer called “adult onset diabetes,” says Mittelman.

"It's very clear the obesity epidemic we are seeing in our kids is helping drive this epidemic," he says, noting that one out of three kids is overweight or obese.

Fitness programs and summer camps

Medical and public health experts are racing the clock to slow the growth of diabetes. They say it’s going to take a societal pivot to change the trend.

When patients at Children's Hospital are diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes or found to be at risk for it, Mittelman says one of the first things the staff does is try to help parents understand the relationship between the disease and being overweight.

"I have a barrier from step one because they don’t recognize their child has a problem," he says. "Oftentimes diabetes and obesity is rampant in that family and so that's their norm, and many of these kids, they expect they're going to get diabetes someday and that's just going to be part of their life and they'll deal with it just like their parents and grandparents did, so they don’t see that as necessarily a problem or as something that they can avoid."

To combat the growth of diabetes among kids, the hospital has a wide range of programs to educate kids and parents who are at risk and to help those who are already living with the disease, says Mittelman.

Along with the farmers market, the hospital hosts fitness programs in the community for kids of all ages and it just launched a new clinic at the hospital for kids with Type 2. One in five kids diagnosed with diabetes have Type 2, he says.

Children’s has also gotten into coordinating summer camps - more precisely, diabetes camps. This summer the hospital hosted or co-hosted several camps that lasted from two days to two weeks in locations ranging from L.A.-area churches to Big Bear.

The camps seek to teach kids that eating nutritious foods and exercise help minimize the amount of medication they need to control the disease.

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health is also trying to help, says Tony Kuo, who oversees chronic disease for the agency. Public Health is creating programs designed to make healthier foods more accessible in areas with high rates of diabetes, and it's working on getting schools to open their grounds after hours for physical activities.

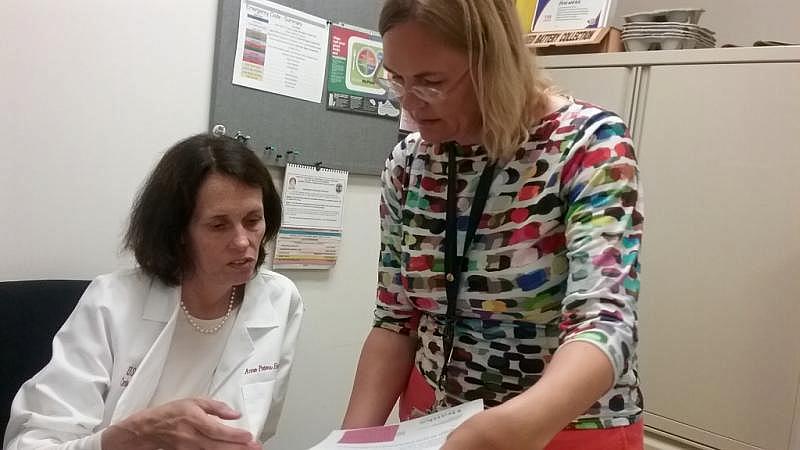

Educating people about the disease and the tools to manage it is also important, says Dr. Anne Peters, a USC Keck Medical Center diabetes expert.

Towards that end, she's writing a manual in very simple English and Spanish that explains how to use technologies like insulin pumps and monitors.

Research on vitamin D, genes and gastric bypass

Dr. Anne Peters, left, with her research coordinator, Valerie Ruelas, at the diabetes clinic Peters founded at the Roybal Health Center in East Los Angeles.

Peters is also conducting research on vitamin D at the diabetes clinic she founded at the Roybal Medical Center in East L.A. Studies have shown that diabetics tend to have low vitamin D levels; she's studying people who are prediabetic to see if they have the vitamin deficiency and if that might affect their chances of developing diabetes.

Dr. Thomas Buchanan, who oversees the division of endocrinology and diabetes at USC Keck, says he has conducted several studies looking at genetics and Latinos, including one that "identified several genes that appear to influence either the risk of diabetes or that affect physiological processes that help control blood glucose." These studies will help doctors identify ways to better treat the disease in some patients, he says.

Buchanan is also looking at how gastric bypass surgeries his team has performed might help those who need to lose 25 to 30 pounds avoid or minimize diabetes. This research is somewhat controversial because gastric bypass is usually reserved for those who need to lose much more weight. Buchanan is focusing on gastric bypass because people tend to keep the weight off after surgery, and he's studying the effect of sustained weight loss on the disease.

Getting people to adopt lifestyle changes because of Type 2 diabetes is particularly challenging because it can take many years for complications to develop.

"You don’t think, 'I’m going to be blind 20 years from now so I need to not eat this piece of pie,'" says Buchanan. "So that’s one of the hardest things about diabetes ... to understand the complications are severe and they really can affect your health and they are going on right now."

[This story was originally published by KPCC.]

[Photos by Elizabeth Aguilera/KPCC.]