Here’s What Honolulu Is Doing To Test Hard-Hit Communities For COVID-19

This article is part of a larger project by Anita Hofschneider, produced with support from the 2020 National Fellowship and a grant from the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Her other stories include:

Community Leaders: State Is Failing Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 1: Hawaii Wanted To Save Insurance Money. People Died

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 2: Health Officials Knew COVID-19 Would Hit Pacific Islanders Hard. The State Still Fell Short

Hawaii Researchers: State Must Support Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Pacific Islanders Have The Highest COVID-19 Death Rate In Hawaii

Women Were Already Struggling At Work. The Pandemic Is Making It Worse

Kalihi Has The Worst COVID-19 Outbreak In Hawaii. Here’s How The Community Is Responding

Hawaii COVID-19 Data For Race And Ethnicity Is Missing

Hawaii Pacific Islanders Are Twice As Likely To Be Hospitalized For COVID-19

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 3: Pacific Islanders Can’t Return Home During COVID-19 — Even To Bury Their Loved Ones

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 4: The Pandemic Is Hitting Hawaii’s Filipino Community Hard

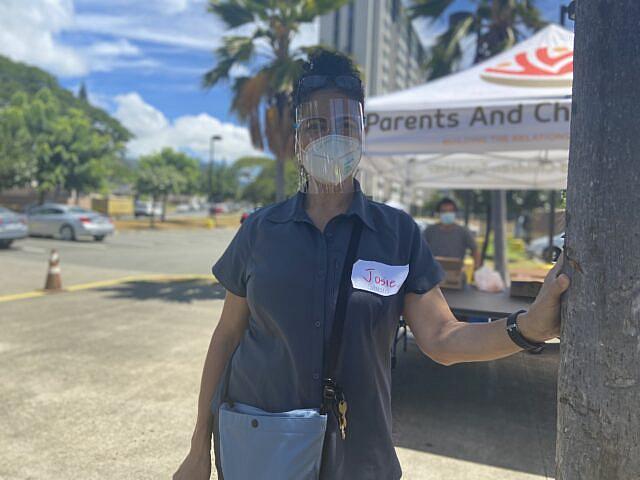

Josie Lesa is a Samoan interpreter. She volunteered at a COVID-19 testing event at Kuhio Park Terrace in Kalihi Wednesday.

The organizers of Wednesday’s testing event at Kuhio Park Terrace were prepared for a crowd. More than a dozen National Guard members sat under six registration tents filling one section of the parking lot in front of the public housing project’s community center.

Orange cones strategically placed in front of the tents formed space for a line, complete with social distancing. Blue arrows taped on the ground indicated where patients should walk to get free coronavirus testing.

But a crowd never appeared. For hours, volunteer interpreters sat idle or urged tenants on a loudspeaker to come get tested. Josie Lesa, a retired nurse who had volunteered to interpret for Samoan patients, was perplexed. By around noon Wednesday, she had spent all morning at the site and said there had never once been a line.

“It makes me sad,” she said as she gazed up at one of the enormous towers that make up Kuhio Park Terrace, Hawaii’s biggest public housing complex. She wondered whether parents were at home teaching their kids virtually, since the testing was advertised as running between 9 a.m. and 2 p.m. on a weekday. “There’s probably thousands of people who could come get tested.”

The pace picked up later and by the end of the day nearly 250 people got tested, according to a city spokeswoman. That’s twice as many as who registered, but still far fewer than the thousands who attended other free testing events.

Wednesday’s event was part of a mass effort to better understand how widespread the coronavirus is in Hawaii. The three-week surge testing, funded by the federal government and organized by the City and County of Honolulu, aims to test thousands of people per day. The idea is to test as many Hawaii residents as possible, whether or not they have symptoms, and to do it for free. The federal government has given Hawaii 90,000 testing kits.

While the main goal is to test widely, Mayor Kirk Caldwell says he particularly hopes to reach Pacific Islanders and Filipinos, who are dying of coronavirus at disproportionately high rates. Pacific Islanders, not including Native Hawaiians, make up 31% of Hawaii’s coronavirus cases according to the latest available data, even though they’re just 4% of the population.

But it’s unclear how well the city is able to reach those communities and to what degree they’ll benefit from the influx of federal funds for testing.

The city doesn’t have a particular goal in terms of the number of Pacific Islanders or Filipinos it hopes to test. Unlike some other states, Hawaii hasn’t been posting racial and ethnic breakdowns of who is being tested, so there’s no data indicating whether or not these communities are being tested in proportion to their population.

Tents for coronavirus surge testing are set up at Kuhio Park Terrace in Kalihi. The city hopes to test as many as 90,000 people during a three-week testing surge.

Janice Okubo, spokeswoman at the Hawaii Department of Health, said the agency doesn’t post racial breakdowns for testing because the city doesn’t normally receive demographic breakdowns along with laboratory test results. The race and ethnicity of patients who test positive are found through subsequent investigations. Caldwell said the company conducting testing for the city now is collecting race and ethnicity data that may be released.

Without that, it may be tough for the city to judge whether its surge testing is a success in terms of reaching hard-hit communities.

The mayor said his main strategy is to locate testing sites in communities where Pacific Islanders and Filipinos live. The city is conducting multiple days of testing in Kalihi.

Borden Bolkeim, a Marshallese interpreter and Kalihi resident, said he appreciates the effort.

“I think this is a big step for the Kalihi community,” he said Wednesday at Kuhio Park Terrace a few minutes after announcing the free testing via loudspeaker in Marshallese.

He wasn’t completely surprised by the relatively slow turnout. He said the requirement for an email address in order to receive COVID-19 test results is a barrier for many elderly Marshallese residents who don’t have email addresses.

“A lot are scared and don’t know what’s going on,” says Bolkeim, who is a member of the Marshallese Community Organization. Despite the underwhelming turnout, he hopes to see more similar events.

Limited Translation

The first day of surge testing in Honolulu was on Aug. 26. Residents were urged to go to the website www.doineedacovidtest.com to sign up. The website is only available in English and Spanish, and has no translations in Filipino or Pacific Islander languages.

People can still walk in and get tested without signing up online, although the city encourages people to register beforehand.

People who get tested are handed a page of instructions describing what to do if you’re positive. So far, the instructions are only in English, although the city is in the process of translating them.

The city hasn’t hired any interpreters to help with testing, and instead is relying on volunteers. Initial announcements about the two-week testing spree were in English. Translated notices describing testing locations were posted on Caldwell’s social media accounts on the fifth day of testing, two days before Wednesday’s event.

Hao Nguyen, interim director at the Pacific Gateway Center, a nonprofit that primarily serves immigrants from Asia, said he signed up to get tested and noticed that the website was not translated into any Asian or Pacific languages.

The City & County of Honolulu announced COVID-19 testing in multiple languages on Monday.

“People who cannot speak English, how can they do it?” he said. “It’s not complicated but if you do not know English, it’s complicated.”

He said surge testing is a great opportunity that should be offered equally to everybody.

“Right now it might not be the case,” he said.

The city should not only provide access to registering for testing in multiple languages, but should also make it clear that interpretation will be provided, Nguyen said. He thinks people with limited English proficiency are less likely to try to get tested if they aren’t sure whether they will be helped.

Ryan Kusumoto, who leads the nonprofit Parents and Children Together that works out of Kuhio Park Terrace, suspects that many people didn’t know about the testing because of the last-minute announcement. He didn’t find out about the testing until the day before and spent part of Wednesday knocking on doors in the housing complex encouraging people to get tested.

But Kusumoto said he was very impressed by the organization of the testing event and appreciative of all the officials who came out. It was an important effort to reach the community, he said, and next time he hopes there’s more lead time and collaboration to encourage people to attend.

A Turnkey Program

Josh Stanbro, the city’s chief resiliency officer who is part of a team organizing the surge testing, said the city is hoping to continually improve access to testing.

“This was a turnkey prepackaged operation from the federal government,” Stanbro said. “The spirit here is, just start doing it and iterate as we go and improve as we go.”

He noted the limited language options for the website also reflects a national problem — Hawaii is far from the only state where Pacific Islanders are getting COVID-19 at high rates.

A sign at Kuhio Park Terrace urges everyone to wear face masks.

Stanbro said the city doesn’t have any interpreters on staff but contracts with an organization to provide interpretation when needed. Not every testing site has interpreters, but events like Wednesday’s at Kuhio Park Terrace had volunteer interpreters for several languages.

A key strategy is to partner with We Are Oceania, a social service organization helping Micronesian Hawaii residents, Stanbro said. The group is helping to spread the word about the testing and recruit volunteer interpreters for the testing sites.

Along with We Are Oceania, a coalition of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander community advocates is also getting the word out. They met with faith leaders in the Pacific Islander community to urge them to tell their congregations about the free testing, and are using donated iPads to help people register.

Advocates say they appreciate that Caldwell is trying to reach out to the Pacific Islander community. Some leaders have felt shut out of Gov. David Ige’s coronavirus response.

Councilman Joey Manahan, who represents Kalihi, said he’s happy with the fact that the city is providing more concerted testing in his district, something that he’s wanted for months.

Barbara Tom, who leads the Safe Haven Immigrant Resource Center in Waipahu, is more concerned about what happens after the testing. When reached by phone this week, she was driving down to the Marshall Islands Consul General office with disinfectant and hand sanitizer, anticipating that they will get calls from community members once tests from the surge events start coming back positive.

“This testing is good to find out how many people are positive but you have to have infrastructure in place to meet the needs if someone turns positive. I don’t know if that’s available,” she said. “I don’t know if they’re really prepared for all the positives that may come out of this testing.”

“Guarantee we’re gonna get calls,” she added. “This week, probably.”'

Civil Beat reporter Eleni Avendaño contributed to this story.

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism National Fellowship and its Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism

[This story was originally published by Honolulu Civil Beat.]