Hidden Threat: Blood supply system lacks key safeguards against dreaded Chagas disease

Dr. Seema Yasmin’s reporting on this project was undertaken as a National Health Journalism Fellow at the University of Southern California’s Center for Health Journalism. Yasmin, a physician and former CDC epidemiologist, is a reporter at The Dallas Morning News and a professor of public health at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Other stories in the series include:

Seven scourges of the tropics have arrived on Texas soil

Hidden Threat: The Kissing Bug is spreading an exotic, bug-borne infection in Texas

A staff member at Carter BloodCare in Addison reaches for bags of donated blood. “We do still screen donors for Chagas by asking them about their health,” said Dr. Laurie Sutor, Carter’s vice president of medical and technical services. “We ask if they feel well.” (Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer)

Patients receiving blood transfusions are at risk of infection with Chagas disease, a tropical illness, according to an investigation by The Dallas Morning News and broadcast partner KXAS-TV (NBC5).

Blood centers screen first-time donors for the disease with a one-off test. Donors who test negative are never screened again and are able to donate blood repeatedly.

New technology that inactivates contagious diseases in donated blood is used to protect the blood supply in some states but not in Texas.

Chagas disease, caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, can lead to heart failure and sudden death. Globally, about 11 million people are infected. An estimated 300,000 live in the U.S. The parasite can hide in heart muscle and the gut for two to three decades before causing symptoms.

One in every 6,500 blood donors in Texas are infected with the parasite that causes Chagas disease, according to researchers at the National School of Tropical Medicine in Houston. That compares with one in every 27,500 donors across the U.S.

The rate is higher in some parts of South Texas, where an estimated 1 in 3,000 donors are infected, experts say. Half of the infected donors acquired the disease in Texas.

Blood centers began voluntarily testing donors for the parasite in 2007. Since then, blood screening has identified more than 2,000 infected donors.

The parasite is spread to humans and dogs through the bite of a kissing bug, an insect that lives in rats’ nests or wood piles or in the nooks of furniture or cracks in homes. Chagas disease is also spread through pregnancy from mother to baby, as well as through organ transplants and blood transfusions.

But blood donors are tested only once for Chagas disease under the current protocol outlined by the Food and Drug Administration. First-time donors who have a negative test are never screened again.

Three federal agencies work with blood banks to monitor threats to the blood supply. The FDA sets guidelines for blood screening, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention performs disease surveillance, and the National Institutes of Health researches the science of blood safety.

Nearly 10 million Americans donate blood each year. Four components of donated blood — red cells, platelets, plasma and cryoprecipitate — are given to an estimated 5 million patients a year.

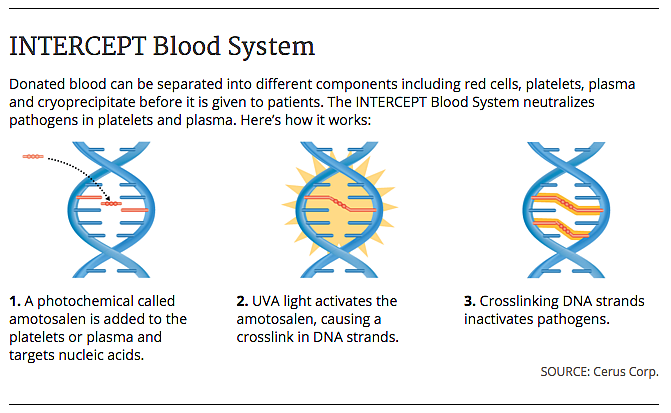

Blood is screened for HIV, syphilis, West Nile virus, hepatitis B and C and other viruses and bacteria each time a person donates blood. New technologies that inactivate blood pathogens including HIV, malaria and the parasite that causes Chagas disease have been recently approved by the FDA.

One of these technologies, the INTERCEPT Blood System, has been used in 20 European countries since 2003. It is now used by some blood centers in Florida and Delaware, and there are plans for its use within the next year at a Colorado blood center and at the National Institutes of Health in Maryland.

The system, made by Cerus Corp. in Concord, Calif., works on plasma and platelets. It uses a chemical that latches on to the genes of various pathogens. The blood is then exposed to ultraviolet light, which tightly binds the chemical to the genes so the pathogens cannot replicate. Plasma and platelets are not affected because they don’t contain genes.

Blood centers in Texas are not using the technology. Blood screening guidelines set out by the FDA do not call for the use of systems such as INTERCEPT. But states and blood centers can choose to go above and beyond federal guidelines.

“We do still screen donors for Chagas by asking them about their health,” said Dr. Laurie Sutor, vice president of medical and technical services at Carter BloodCare, the largest blood supplier in Texas.

“We ask if they feel well,” said Sutor, referring to a questionnaire that donors fill in before they give blood.

But many people infected with Chagas disease feel well for decades. That’s because the parasite can lie dormant for 20 to 30 years before causing heart and gut symptoms.

One in three people infected with the parasite will develop chest pain, fatigue and breathlessness from heart failure that can be fatal. One in 10 suffer damage to the nerves and gut. Between 1 percent and 10 percent of pregnant women pass the parasite on to their babies.

“Americans are sitting ducks waiting for an epidemic to happen,” said Dr. Richard Benjamin, chief medical officer at Cerus. From 2002 to 2015, Benjamin was chief medical officer at the American Red Cross, where he supervised donor and patient safety.

One-time screening might be appropriate in states where Chagas disease is not common, he said, but in Texas, where rates are higher, there should be a more rigorous protocol.

Sutor disagrees. “The experts in our field feel that the current screening methods are accurate even in Texas because the evidence right now is that Chagas is not being transmitted by blood transfusions,” she said.

The CDC and FDA say that Chagas disease can be spread by blood transfusions. In a 2010 FDA guidance document for blood banks, the agency said that transfusion-related Chagas disease infections are “not likely to be diagnosed, and in many cases, even if symptoms appear, infection may not be recognized.”

Seven people have been infected with Chagas disease after receiving blood transfusions in the U.S. and Canada, according to the FDA. Five have been infected after organ transplantation. Since screening began, two people have been infected from platelet transfusions.

The same FDA document says that in Los Angeles, one in every 2,000 blood donors may be infected with the Chagas-causing parasite. “That’s really a very high number,” said Benjamin. “Much higher than for any other infectious disease that we deal with routinely, like hepatitis or HIV.”

The FDA declined to be interviewed, as did the chair of its blood safety committee. In an emailed statement, an FDA spokesperson said the agency continues to work with the CDC and National Institutes of Health to monitor threats to blood safety and ensure that the medical community is aware of risks associated with blood transfusions.

Another tropical disease that can spread through transfusions is West Nile virus. By the time blood banks started screening for the virus in 2003, at least 23 people had been infected by tainted blood.

A staff member works at Carter BloodCare in Addison. A technology exists that can keep pathogens in donated blood from replicating. But federal blood screening guidelines don’t call for its use, and blood centers in Texas don’t use the technology. (Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer)

West Nile virus and the parasite that causes Chagas disease aren’t the only tropical agents threatening the safety of the blood supply.

Chikungunya, a virus spread by mosquitoes, has caused outbreaks in the Caribbean in recent years, and experts warn that it could become established in Texas.

The risk is that when a traveler brings the virus to Texas, the virus could circulate among local mosquitoes and become established in mosquitoes and humans.

A chikungunya epidemic in Puerto Rico last year forced a shutdown of the local platelet donation system. The American Red Cross stopped accepting donations from locals and had to import platelets from the continental U.S.

Benjamin fears a similar situation could occur in Texas.

“I’m concerned, and I think there should be a more general concern than there seems to be,” he said. “It’s time to consider Chagas again and look to see if what we are doing is correct or not.”

[This story was originally published by The Dallas Morning News.]