Historic vote could freeze Bay Area refinery emissions levels

Marissa Ortega-Welch wrote this story while participating in USC Center for Health Journalism‘s California Fellowship.

Cropped photo via Flickr by rmcnicholas

This is a policy story that’s really about people.

You might not know that from the title of the workshop I’m about to go into: the Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD) informational workshop on Regulation 12 Rule 16. Sounds pretty wonky, right?

Just outside the meeting, however, it looks and sounds more like a protest. The 20 or so people gathered in front of the Richard Memorial Auditorium holds signs that say “Protect our health” and “We want clean air.” An organizer leads them in a chant: “When our communities are under attack, what do we do?” “Stand up, fight back!”

These people have been coming to meetings like this for five years. They know that the policy being discussed inside could have a real effect on their lives. In 2012, an explosion at the Chevron Richmond refinery sent 15,000 residents to the hospital. Groups like Communities for a Better Environment and Asian Pacific Environmental Network— which were already pushing for more regulations on the refinery — really doubled down after that.

Tonight the air district — the agency that issues Spare the Air Days and regulates emission from industries and residencies — is discussing a proposed cap on greenhouse gases and other pollutants coming from the five Bay Area refineries. This cap, if passed, would essentially freeze local refineries at their current levels of production. They wouldn’t be able to refine more oil than they do now without radically changing their infrastructure to process more cleanly. The air district is seeking public comment before the board votes on the proposal in May.

DOCUMENT: Read the air district's presentation on the proposed rules

The community members chant their way into the air district meeting and take their seats, next to men and women donning blue Chevron fleeces embroidered with “Bay Area Refinery Worker” on the sleeve. This public forum is fairly basic protocol for any draft regulation, but tonight the atmosphere is heated and the crowd is divided.

One by one, people step up to the microphone to make their comments. Community activists say that the Bay Area needs this cap to keep the pollution that refineries create from getting worse — pollution that affects the health of people nearby. Industry employees are worried that the increased regulations will put them out of work.

I pull aside Torm Nompraseurt, a long-time Laotian community leader who works with the Asian Pacific Environmental Network. He’s in his 60s and is one of those community organizers who’s tried to retire for years, but keeps coming back. Nompraseurt says a lot of Laotian people came to the East Bay as refugees after the Vietnam War, and many now suffer from health issues like asthma and other respiratory problems.

Torm Nomprasuert (right) stands with family friend Seingther Lathanasouk (left) in front of Lathanasouk's Richmond home, which is less than a mile from the Chevron refinery.

Whenever someone in the Laotian community passes away, Nompraseurt attends the funeral. He says there have been more and more recently. These days, he says, he’s been going to a funeral service at least once a week.

Many of these people are dying of cancer. “I can count on my fingers,” he says, “We have five people diagnosed with cancer right now.” They are friends his age, but also younger people like his niece’s grandson, who is 17 years old and grew up right across the railroad from the Chevron refinery.

Nompraseurt can’t be sure these cancers are caused by the refinery. Richmond is home to many industries, as well as a busy freeway and a port, all of which create their own pollution. The specific pollutants created by refineries — things like sulfur dioxide and particulate matter — are known to cause respiratory illness, heart disease, even cancer. That’s why Nompraseurt supports the cap. He doesn’t want the oil industry to be able to pollute more.

A few of days after the meeting, Nompraseurt meets me at the home of his family friend. It’s a modest house on 8th Street in Richmond, less than a mile away from the Chevron refinery. From the front of the house, you can see the industry’s smoke stacks and storage tanks rising up on the hill just above the city.

We go inside and meet 74-year-old Siengther Lathanasouk who lives here with his two adult children and three grandchildren. Lathanasouk’s friend Inn Villayngeun is also over at the house today. The two men met as soldiers in Laos and came here as refugees. Now, their granddaughters play together while we talk, quietly running in and out of the house and whispering to each other.

The home is neat but cluttered. The family room walls are covered with the former Laotian flag, a framed copy of Lathanasouk’s U.S. citizenship certificate, and old photos of soldiers in Laos. Lathansouk walks with a cane and can’t see out of his clouded right eye, but when I take an interest in the photos on the wall, he eagerly hops onto a stool to bring down one of the photos and show it to me.

Pictured are four soldiers, standing in a jungle. Lathanasouk points out one of them - it’s his wife. With Nompraseurt as a translator, Lathanasouk tells me that she was also a soldier and fought in the resistance against the Laotian communist government.

We all settle down on stools to talk about the reason I’m here today: to find out if these families have experienced health issues living so close to the refinery.

Inn Villayngeun says he’s had a cough since the 2012 Chevron explosion. He used to live and work as the manager of a low income apartment complex in Richmond right across from the oil refinery and was there on the day of the explosion. His boss called him to tell him there was a “shelter in place” warning and to have everyone go inside and close all the windows.

When he woke up the next morning, Villayngeun said it looked like yellow snow covering the streets, cars, and bushes. He was coughing and it hurt to breathe. When he went to the hospital it was packed with people.

I had to wonder: For these guys who were resistance fighters in the Laotian jungle, did this yellow chemical dropping out of the sky remind them of their time in the war?

Everyone gets to talking about this and Torm Nomprasuert speaks for the group. In Laos, he explains, “When an airplane come and dropped a bomb, everybody knows and runs and hides.” Here in Richmond, however, when chemicals are released, “We cannot run; we cannot hide,” he says, and often the pollution is invisible. “Here, the chemical is everywhere.”

Not just a Richmond issue

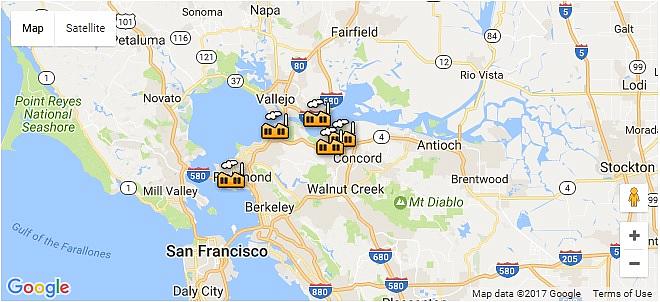

Jennifer Sundberg is another refinery town resident concerned about the industry’s health impacts. She lives about twenty miles away in Benicia. While Richmond’s Chevron refinery often gets the most attention, the Bay Area actually has four more. There is a Phillip 66 refinery in Rodeo; two refineries in Martinez, one owned by Tesoro and the other by Shell; and a Valero refinery in Benicia.

Sundberg and her husband moved to Benicia from Sacramento. They wanted to be closer to her dad but didn’t think they could afford to live in the Bay Area.

“I didn't even consider living here because of the refinery!” she says. “But my father basically talked to me about the fact that, you know, the breeze blows in the other direction.” So Sundberg looked into the air quality. “We were trying to find a place that we could raise our children,” she says.

Sundberg has two kids, a four year old and a nine year old. She says her oldest has asthma and chemical sensitivity, which she didn’t know when they moved here. She told me she actually asked her son’s doctor when he was diagnosed with asthma: Should we move?

MAP: Where are Bay Area refineries?

The fact is, all of us driving on the freeway emit more greenhouses gases than the Bay Area’s five refineries combined, but refineries do emit high amounts of sulfur dioxide, which turn into particulate matter that affects asthma.

Because of her son, Jennifer has gotten very involved in local groups, fighting for everything from more regulation of the refinery to serving organic foods in the schools.

“There are so many different factors”

I bring up Sundberg’s concerns, and those of the people I met in Richmond, with Dan Peddycord. He’s the Director of Public Health for Contra Costa County – where four out of five Bay Area refineries are located. I ask him if these people’s health problems are caused – at least in part – by living near refineries?

Peddycord explains that in a metropolitan area like the Bay Area, it’s really hard to tease out if someone’s asthma or respiratory illness is caused by the refinery they live by, the freeway they drive on, the place they work. There’s also genetics – do they have asthma or cancer in their family history? And there’s socioeconomic factors too – how much money they make, whether they have health insurance, if they’re exposed to a lot of stress like from surviving a war.

Peddycord says, “Refineries contribute to what's in the air and what we breathe and what we're exposed to” but they aren’t the only source. “Generally what we're really talking about is sort of your lifetime accumulated exposure,” he says. “From a public health perspective, our interest is to see you lower those exposures from all different sources.”

A crude proposal

Andres Soto (blue shirt) demonstrates with activists from Communities for a Better Environment and Asian Pacific Environmental Network outside an air district public workshop in Richmond, Calif.

Andres Soto, an organizer with the group Communities for a Better Environment, has lived his whole life near refineries. He grew up right next to Chevron and went to Richmond High School. “Our mascot was the Oilers,” he tells me. “That dates back way to the early 20th century when they were proud of being an oil town.”

Soto has worked on oil industry regulations for years. Prior to pushing for the refinery cap, he has been working to stop “crude by rail’ from coming into the Bay Area. That’s the term used when unprocessed oil is shipped in train cars to refineries. We’re seeing more and more of this lately.

Bay Area refineries usually get crude oil from within California or from Alaska, but those sources are drying up. So now the industry is turning to oil fields like Tar Sands in Canada, and Bakken in North Dakota, shipping oil from these inland states out to refineries which are almost all on the coasts. Oil from these places is very flammable. Because the railways cut right through many residential areas, some residents are calling this system a “bomb on wheels.”

More than 24 derailments have occurred in the U.S. and Canada since 2013, resulting in fires, oil spills and the evacuation of towns. One train in Quebec exploded in 2013 and killed 47 people. The incident sparked protests against crude by rail across the country, including here in the Bay Area.

Once it gets here, the processing of Tar Sands or Bakken emits more greenhouse gases or toxic chemicals than the oil we’ve processed in California up to this point. That’s why community groups like the one Soto’s involved in have fought crude by rail and have pushed for this refinery cap. They want to keep these new kinds of oil out of the Bay Area.

“If there’s local caps, you just choke a business out”

Lifelong Richmond resident Mike Miller thinks refineries have already been doing their part to reduce pollution.

“I remember when I was young when and I was on the freeway, you could smell the refineries,” he says. “You can drive by now you can’t smell. So things continue to get better every day.”

Miller works at the Phillip 66 refinery in Rodeo. He’s been there 26 years, and he’s the President of United SteelWorkers Union Local 326. He’s glad refineries are cleaner than they were decades ago; but he is against a hard and fast cap.

“If there’s local caps” on refineries’ emissions levels, he says, “You just choke a business out.”

Miller thinks the industry will just shift production outside of the Bay Area – to somewhere with less regulation. “We would not want to see a California refinery closed that makes the cleanest fuels in the United States here right now and open up somewhere else,” he says. Then the Bay Area would have to ship in gas, which would create greenhouse gas emissions in itself. “So we're just moving the carbon footprint somewhere else.”

Even some people at the air district oppose the refinery cap. The agency is made up of staff who are directed by a board of 24 elected officials. The board tasked the staff with drafting the refinery cap proposal, based on requests from groups like Communities for a Better Environment and Asian Pacific Environmental Network. Eric Stevenson, director of meteorology, measurement and rules at the air district, told me the board’s action was unprecedented.

“I've been here at the district for 25 years,” Stevenson says. “This is the first example of something where the board has said to staff, ‘We recognize you have concerns but we're directing you to develop this proposal.’”

DOCUMENT: Read the air district staff report on the refinery cap

The staff is also concerned that the air district doesn’t actually have the legal authority to regulate pollutants coming from one specific industry. They also don’t normally set hard numeric caps on pollutants. While the air district is used to being sued by industries over increased regulation, Stevenson is concerned that the refinery cap rule won’t stand up in court.

“What we don't want to do is lose because it's not efficient,” he says. “Then we're wasting time, wasting the public's money, fighting legal battles.”

Stevenson has concerns about the refinery cap’s economic impact, too. According to the staff analysis, the cap would not significantly affect jobs; it would simply keep the refineries running at current production levels. However, if the demand for fuel increases in the Bay Area, the refinery cap could result in higher gas prices because the cap limits the refineries from being able to produce more.

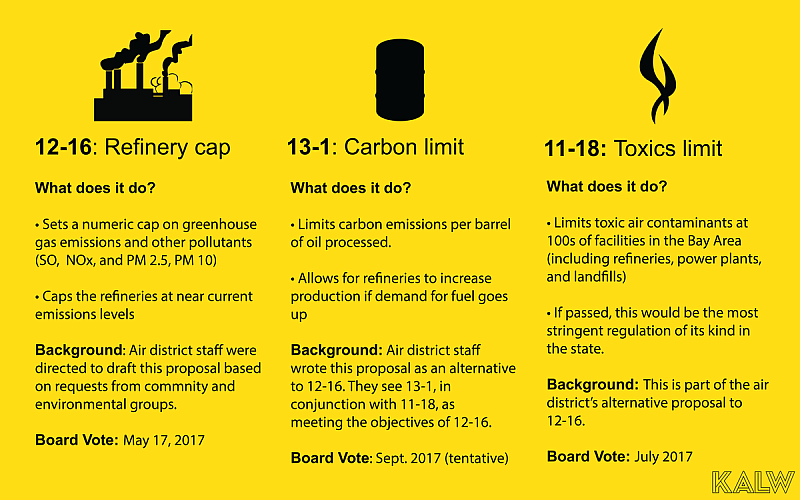

That is why air district staff came up with an alternative proposal, which the board will vote on later this year. Instead of hard caps on each facility, their proposal would limit greenhouse gases per barrel of oil. That would require refineries to be more efficient, but they could still increase oil production. Stevenson says this regulation, along with another proposal to limit toxic air contaminants from refineries, addresses the health and environmental concerns of the refinery communities.

GRAPHIC: Three proposed rules regulating refinery emissions

The Bay Area Air Quality Management District has three different proposals on the table right now that would affect refineries' emissions. Proposals 12-16 and 11-18 are currently undergoing environmental review. Proposal 13-1 is still being developed.

“A fundamental issue of justice”

Community activists — and some air district board members — say the staff’s proposals are not enough. They argue that greenhouse gas emissions and pollution need to be capped at current levels.

Oakland City Councilmember Rebecca Kaplan sits on the air district board that will vote on the refinery cap proposal this May. “What we’re fighting for with the refinery cap,” she tells me, “is limiting the pollution that impacts the immediate surrounding community.”

Kaplan says this is a “fundamental issue of justice.” She says California’s cap-and-trade program — which allows industries to increase emissions at one location as long as they decrease emissions somewhere else — is inequitable.

“The problem with air pollution is not just what is the average air pollution throughout the state of California, which on any given day might be fine if you average it,” Kaplan says, “The problem is that you have some communities that live right next to heavily polluting facilities such as oil refineries and in those communities you see incredibly disproportionate impacts of asthma and other diseases.”

Kaplan isn’t the only one that thinks this. Just last week, the California Air Resources Board, the state level air quality agency, came out in support of all three of the Bay Area Air District’s refinery rules, urging that “more can and must be done to deliver real reductions in the pollutants that are impacting the health of residents living near refineries.”

EXTRA: Who is your representative on the BAAQMD board?

Plus, California actually passed legislation last year to address some of the inequities of the cap and trade program. Assembly Bill 197 requires the state to prioritize “direct emissions reductions” in order to address the local impact that big polluters’ have. The problem is, the legislation is vague and no one exactly knows how to translate it into concrete policies.

Kaplan wants to see the Bay Area take a leadership role on this issue, especially considering that the Trump administration has started making efforts to roll back environmental regulations.

Kaplan says that sometimes people talk wishfully about having a Bay Area-wide government.

“We do have Bay Area government,” she says. “The Bay Area Air Quality Management District board is a Bay Area government with governmental powers to order things done, to issue fines to spend money, and with legislative authority to act to clean up our air.”

Kaplan wants to see the air district “do what's in our hands to do” and pass the refinery cap.

What is in our hands to do? Whatever you think about this regional decision, the Air District wants to hear from you. It is soliciting public comment on the proposed cap on greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants for oil refineries. Bay Area residents can weigh in until May 8 by emailing Gregg Nudd at gnudd@baaqmd.gov.

[This story was originally published on KALW.com. Click on the audio player link below to listen to the radio piece.]

[Photos by Marissa Ortega-Welch/KALW]