How 2 rival hospital systems provide emergency medical services to Springfield area

This article was originally published in the Springfield News-Leader with support from our National Fellowship and the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

An ambulance delivers a patient to the Burge emergency department in this undated historical photo.

Provided By CoxHealth

A "handshake agreement" in the '90s established a unique partnership between two health systems that has grown to support emergency medical services in the Ozarks. It's the only one of its kind in Missouri, according to CoxHealth EMS Business Manager Kyle Meadows.

Mercy Hospital Springfield — then St. John's Regional Health Center — and CoxHealth began working together to provide emergency medical services in 1987, based on past News-Leader reporting. Prior to that, the city was served by private ground ambulance services.

"We’re very fortunate in southwest Missouri because we have some health systems that are involved in EMS and find it important, which is very nice," said Bob Patterson, Mercy Emergency Medical Services executive director.

The two systems work so well together that they even swap employees from time to time.

"We work pretty well with Mercy, hand-in-hand. Our protocols are slightly different but both medical directors have worked together for years. There’s always grumblings here and there administratively because it’s a different system …," Meadows said. "But I can tell you in EMS, the people are great — as weird as it sounds we’ve hired people back and forth because benefits change."

While the hospital systems coordinate well on EMS, that nearly 40-year-old agreement makes them different from many other ambulance services in the area.

"Greene County has no ambulance district. There’s no tax money at all that pays for ambulance services in Greene County," Meadows said. "We both have an entire county license but a hand-shake agreement dozens of years ago created those boundaries where, basically, our own hospitals are in our own districts."

How did Springfield's ambulance system develop?

The emergency medical service system as we know it today is a relatively young field.

While the concept of taking aid to injured patients has existed for a long time, the structure of EMS that current residents are familiar with didn't develop until the 1960s, according to "The Formation of the Emergency Medical Services System" by Manish N. Shah.

"By 1960, a patchwork of unregulated systems had developed, with services sometimes being provided by hospitals, fire departments, volunteer groups, or undertakers," Shah wrote. "Physicians staffed some ambulances, while others had minimally trained or untrained personnel."

Springfield's privately owned ambulance services were no exception: A 1987 Springfield News-Leader article reported that in the '70s, most services were run by "independent companies or funeral homes."

Mercy purchased one of Springfield's private ambulance services in January 1982. Cox wouldn't enter into the general ambulance game for another five years, although it did run a "Mobile Coronary Care Unit" starting in 1971.

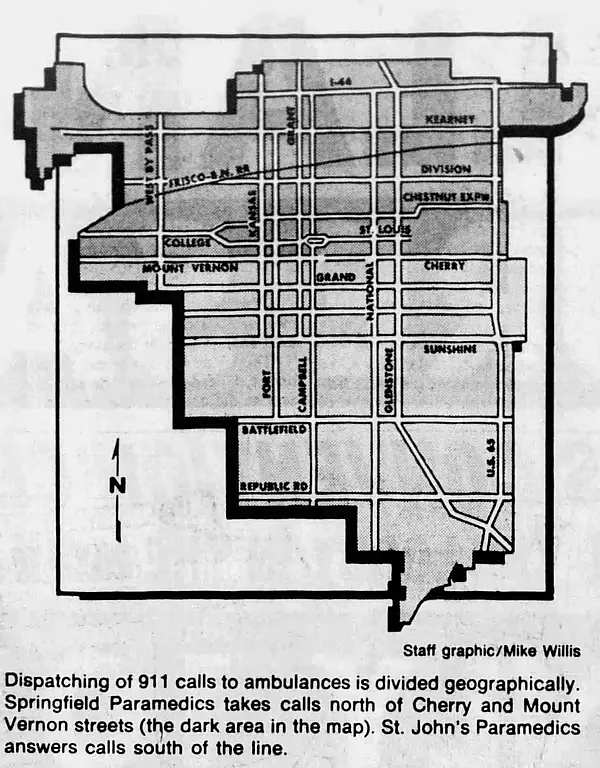

This graphic from the March 22, 1987 edition of The Springfield News-Leader shows how St. John's Paramedics and Springfield Paramedics divided up calls in Springfield.

The Springfield News-Leader/Newspapers.com

In 1987, the News-Leader reported that Springfield was divided between private service Springfield Paramedics and Mercy's paramedics, with the imaginary line running along Mount Vernon Street. (The original dividing line was established by court order in 1981, when both ambulance services were privately owned.) Later that year, Cox purchased Springfield Paramedics, and took on responding to the 911 emergency calls north of Mount Vernon Street.

As Springfield has grown and as both systems have expanded, so has the way the hospitals serve the town. In 1990, new boundaries were established, in part due to the addition of Cox South, which opened in 1985. The boundaries were revised a year later due to Cox cutting back hours at a northwest station.

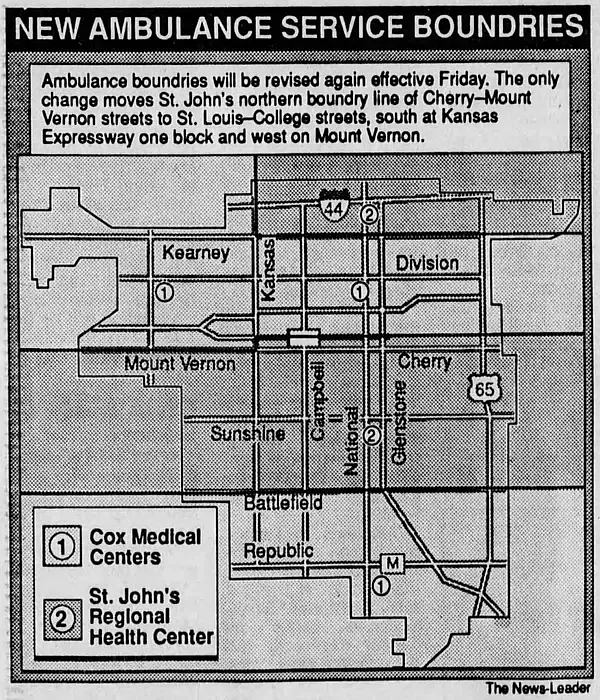

This graphic from the March 14, 1991 edition of The Springfield News-Leader shows how St. John's EMS and CoxHealth EMS divided up calls in Springfield.

The Springfield News-Leader/Newspapers.com

Cox responded to calls south of Battlefield Road to the city limits, calls north of the Cherry-Mount Vernon Street line up to Kearney Street, and calls on or north of Kearney west of Kansas Expressway. St. John's responded to calls on and north of Battlefield Road to the St. Louis-College streets line and calls on or south of Kearney Street east of Kansas Expressway one block and west on Mount Vernon.

The current boundaries, according to CoxHealth EMS are largely the same: Cox EMS responds to calls south of Battlefield Road to the city limits; calls north of Mount Vernon up to Kearney, plus everything in the county that is west of Haseltine Road and south of Kearney. Mercy now takes the north side, from Kearney Street up to the county line; as well as calls on and north of Battlefield Road up to Mount Vernon Street, from Haseltine in the west on east to the county line.

"If an emergency pops up, and there’s a more appropriate unit closer to the call, we just call them up and transfer them the call, as long as they’re available," Meadows said.

Today, Cox EMS serves outlying areas of Greene County, as well as Christian, Webster, Douglas, and Dade counties.

Mercy EMS serves portions of Oklahoma, Arkansas and "a lot of southwest" Missouri, according to Patterson. Mercy recently became the sole provider for Stone County, which voted to form a tax-supported ambulance district, something that hasn't been done in Missouri in the previous 20 years, Patterson said. (Meadows said Cox will still be around to help with mutual aid.)

“That, I think, is the key to sustainability for EMS programs, especially in rural communities, is some type of partnership with the community, whether that’s an ambulance district or whatever that is," Patterson said. "It’s just not sustainable for what we call ‘fee-for-service,’ so just charges to the patient. It’s just not sustainable. Medicare and Medicaid generally do not offset the cost of provision of service, so it’s very challenging.”

Boundaries, technology have changed, but some things haven't

Patterson is in his 37th year with Mercy. Prior to that, he was a flight paramedic in Austin, Texas, and served in the Coast Guard. He's seen changes both at Mercy and in the EMS field in general.

"EMS has just advanced tremendously over the last 40 years. It’s been a lot of work on a lot of people’s parts: EMS physicians are now prominent where before you might have had a medical director who was also the family medicine doc next door, now it’s really physicians who have a keen interest in EMS who are in some cases board-certified as EMS physicians …," Patterson said. "I think that’s the difference, just having folks that are driving us forward, focusing on what’s important, and making those critical changes and doing the best we can in vital moments."

Bob Patterson is Mercy's EMS director. He is in his 37th year with the hospital system.

Provided By Mercy

As more people move into more rural areas like Stone County, Patterson has seen call volume, as well as challenges, increase.

"Thirty, forty years ago this was a pretty quiet area. Folks were on call at home, when you would get a call and have to go back to the station and get their ambulance ...," Patterson said. "The aircraft wasn’t here when we started, so moving the aircraft into those areas is another way we kind of addressed those rural EMS challenges."

Air ambulances allow EMS to quickly respond to traumatic situations in isolated areas, such as a recent rollover crash in Shell Knob, Patterson said. While the crash was less severe than anticipated, the aircraft was able to get to the scene before the ground ambulance and begin assessing the patients.

Clinical practice has also changed.

“Forty years ago ... we could do basic EKGs, IVs, medications but all those have advanced," Patterson said. "Now it’s 15-lead (EKGs) transmitting those to the ER so the cardiologist can see them."

CoxHealth EMS Business Manager Kyle Meadows stands in the CoxHealth EMS Command Center at Cox North in Springfield on Sept. 18, 2025.

Susan Szuch/Springfield News-Leader

Meadows, who has been a first responder since he joined a fire department in 2005, has watched Cox's outcomes improve thanks to their EMS medical director Dr. Matthew Brandt. Brandt developed quality assurance/quality improvement metrics over the past 10 years that have provided much-needed data not only for Cox but for the EMS field as a whole.

"When EMS first started, (the idea was) these were emergency treatments that physicians do in the hospital, they should work out there (in the field). That’s kind of how it started and there wasn’t a whole lot of data to back that up. The whole industry is only 50 years old," Meadows said.

These days, every treatment that Cox EMS provides — at least "the more critical stuff, not Band-aids" — triggers a four-question analysis of the situation.

"In that four question process, a miss — they’re just yes/no questions — on any of those four questions is considered ... error isn’t the right word because it might be the right thing to do, it just didn’t work (but) we’ll use that word for now. Our error rate since we’ve been measuring it has been steadily dropping, from the 8% range to the 1-2% range" over the last 10 years, Meadows said.

"We can empirically tell you that we have one of the best EMS services in the country."

Despite the evolution of technology and training, the goal remains the same, Patterson said.

“Thirty-five years ago when Mercy and Cox really started getting into this business, it was kind of a ‘go help those communities where we’re needed,’" he said. "We’ve always kept that approach. If a community asks us to come in and look at that service, we’d go in and talk with the community."