How one small Iowa city continues to deal with the effects of a major outbreak

This story was produced as part of a project for the 2021 National Fellowship, a program of USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories by Natalie Krebs include:

Nearly two years into COVID, worker safety is still a concern at meatpacking plants

COVID cases in meatpacking plants impacted workers and their rural communities

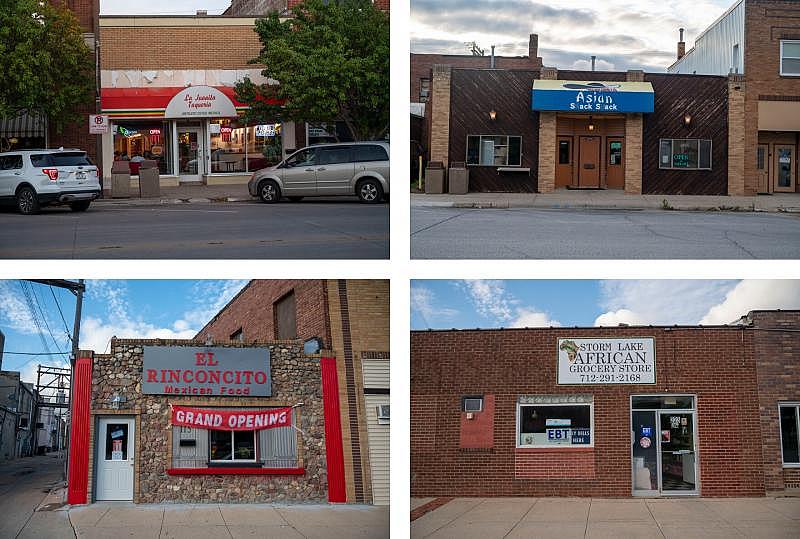

Storm Lake is home to a population where more than a third identify as Latino or Hispanic and nearly one in five identify as Asian.

Natalie Krebs

To read this story in Spanish, click here.

Emilia Marroquin has experienced first hand just how much Storm Lake has changed in the past two decades.

On a driving tour of the town, she points to a building out the window of her car.

“The only Mexican restaurant that was in town was on this corner, [and] there were white people running the restaurant,” she said.

Marroquin, a native of El Salvador, moved to Storm Lake with her family in the 1990s from California to escape increasing crime rates. They were tipped off about the small western Iowa town by a friend’s mother.

When Marroquin, her husband and her young son arrived during a snowstorm in November, Marroquin summed up her experience in one word.

“Horrible!”

Marroquin said at first, the family lived in a hotel as they struggled to find housing in Storm Lake.

She knew no one else who spoke Spanish, so she learned to order by number at the Burger King by the hotel.

“I knew the numbers,” she said, with a laugh. “I knew number 8 was for the chicken nuggets for the kids.”

Di Daniels (left) and Emilia Marroquin are members of Salud, a community based health organization. Marroquin, a native of El Salvador, moved to Storm Lake from California in the 1990s. Natalie Krebs / IPR

Marroquin and her husband got jobs at the Tyson Foods plant, a job they were able to secure even before leaving California.

She lasted just a few days in the harsh work environment.

“I remember the second day I was crying, saying ‘I’m not coming back to this place. I don’t like it. I hate it,’” she said.

But the family stayed in Storm Lake. Marroquin left Tyson, started a new job, learned English, eventually picked up high school and college degrees, and got involved in many aspects of community life.

She’s now one of many immigrants who proudly call Storm Lake home.

Marroquin points out her window to Chautauqua Park alongside the town’s namesake lake, describing the town’s big Fourth of July celebration.

Storm Lake sits on its namesake lake, which attracts tourists in the summer to its city owned resort. Natalie Krebs / IPR

“This is the main area for diverse foods,” she said. “If you want to come, Fourth of July, you can find Mexican food, Ecuadorian food, Asian food, in one place, one spot.”

In a state like Iowa where 85 percent of the population identifies as white alone, according to the most recent census, Storm Lake stands out.

Buena Vista County, where Storm Lake is located, is considered the most diverse county in the state, according to the most recent census.

The town’s official population is 11,269. But most town officials agree it’s likely higher, due to the high number of transient workers and lower than average census turnout rate.

According to the 2020 Census, 37 percent of city residents identify as Hispanic or Latino, nearly the same percentage who identify as white. Nearly one in five identify as Asian.

“It is probably the most unique community in the state of Iowa,” said Mike Porsch, the mayor of Storm Lake.

Mike Porsch is the mayor of Storm Lake. Porsch spent much of his childhood in Storm Lake and graduated high school when the town was mostly white. He has welcomed the demographic shift. Natalie Krebs / IPR

He remembers his graduating class in the 1970s being almost exclusively white. He’s welcomed the change.

“It's so beneficial to the kids that graduate from here because they know what the real world is like,” Porsch said. “I mean it isn’t an all white real world out there.”

Storm Lake’s demographics have shifted dramatically in the past 30 years. According to the 1990 Census, 95 percent of the town identified as white. Just 3.5 percent identified as Asian, and 1 percent identified as Hispanic.

The driving force behind the diversification of Storm Lake is the town’s pork and turkey meatpacking plants. They’re currently owned by Tyson Foods, but have existed in the community under different ownerships for decades.

The plants have pulled in thousands of immigrant workers over the past two decades. They’re the economic center of the town, employing around 3,000 workers.

Immigrant families are vital to smaller, rural communities like Storm Lake that have seen their populations shrink in recent years.

Storm Lake is home to a population where more than a third identify as Latino or Hispanic and nearly one in five identify as Asian.

They start small businesses and fill vacant positions across town, Porsch said.

“They provide the workforce for our restaurants or cashiers out of, you know, Hy-Vees and Fairways, and they’re receptionists at the clinics,” he said. “I mean, they've filled the job void throughout the community.”

The Tyson plants’ impact is clear just from driving through Storm Lake. The plants can be seen throughout town, poking out behind preschool and cemeteries.

Large steel trucks full of pigs regularly pass through the main roads, just blocks from shores of Storm Lake where Tyson sponsors things like lakeside snack stands.

Tyson signs advertising generous sign on bonuses and starting wages appear everywhere from the lawn in front of City Hall to billboards on Hwy. 71, just across from the lighthouse-themed sign welcoming visitors to Storm Lake.

When Tyson’s pork plant experienced a COVID-19 outbreak in spring of 2020, it sent large ripples through the community.

On May 28, 2020, Tyson announced it was shutting down its pork processing facility for several days after state health officials confirmed the outbreak.

The Tyson facilities can be seen throughout Storm Lake. The first plant opened in the town in the 1930s. Natalie Krebs / IPR

The company put out a press release several days later stating internal testing found 591 of its 2,303 employees at the pork plant tested positive for the virus — or one-quarter of all employees — with 75 percent not showing any symptoms.

Porsch said, at the time, finding the balance between protecting workers and keeping the food supply and the economy going was challenging for Tyson and the community.

“[It’s] kind of a Catch-22,” he said. “You'd really love to have time off work to try to get it under control and then bring workers back. But then the other part is, then you're not providing food for the country.”

‘It was just out of this world’

St. Marys Catholic Church has many parishioners from the immigrant community. Father Brent Lingle (right) and Deacon Hector Mora, who used to work in the Tyson turkey plant, comforted many meatpacking workers during the outbreaks. Natalie Krebs / IPR

Research has shown the spread of COVID-19 was significantly greater in meatpacking communities across the country like Storm Lake.

According to a study in Food Policy, counties with large pork processing facilities saw per capita transmission rates increase 160 percent when compared to counties that didn’t have plants.

Counties with large beef processing plants saw per capita transmission rates increase by 110 percent, while those with chicken processing facilities transmission rates increased 20 percent.

Deacon Hector Mora worked in the Tyson turkey processing plant for more than a decade before he left to work for St. Mary’s Catholic Church in May of last year, the same month as the outbreak at the pork plant.

Mora, who’s originally from Mexico, moved to Storm Lake from nearby Denison after his wife first made the move to work in a Tyson plant. When he quit, he had been a supervisor for three years.

He said he felt Tyson took many precautions to protect workers, but said many workers confided in him at the time that they were really scared.

Signs around town advertises higher wages and sign on bonuses to attract more workers as the industry is experiencing a workforce shortage. Natalie Krebs / IPR

“I used to tell them, ‘just calm down, I know we have a bad situation. But don't let these fears be controlling you all the time,’” he said.

The outbreak hit the town’s Microneasian and Latino communities particularly hard, said Father Brent Lingle, who’s been the pastor at the church for two years.

“I would look back at the burials that I did of COVID-related deaths, and a majority of those were from our Micronesian community. Second would be in our Hispanic community,” he said.

The outbreak strained Storm Lake’s health care infrastructure.

At the United Community Health Center, Dr. Natalie Schaller recalls how the federally-qualified health clinic, which services many uninsured patients and underserved communities, made a makeshift COVID clinic out of a conference room.

Natalie Schaller is a doctor at the United Community Health Center in Storm Lake. She works with many meat packing plant workers and their families. Natalie Krebs / IPR

“It was just out of this world. It was unlike anything that I've ever experienced outside of, like, traveling and working in underserved third world countries, I guess,” she said.

Schaller has worked at the clinic for about eight years. Her patients come from a wide variety of cultures. Many are meatpacking workers and their families.

One way she said she’s learned to bridge cultural gaps and build trust with her immigrant patients is to embed herself in their communities and create long-lasting relationships with whole families.

“I might coach some of their children in soccer. And we're there on the weekends together, building a bond and getting to know each other better,” she said.

Schaller said the time period around the outbreak was physically and emotionally draining.

“You know, honestly, just a part of being in this community is knowing and loving some of the people who struggled the most, and ultimately passed away,” she said.

'It does take more time and dollars'

But many say the fallout from seeing so much illness in a small community is ongoing.

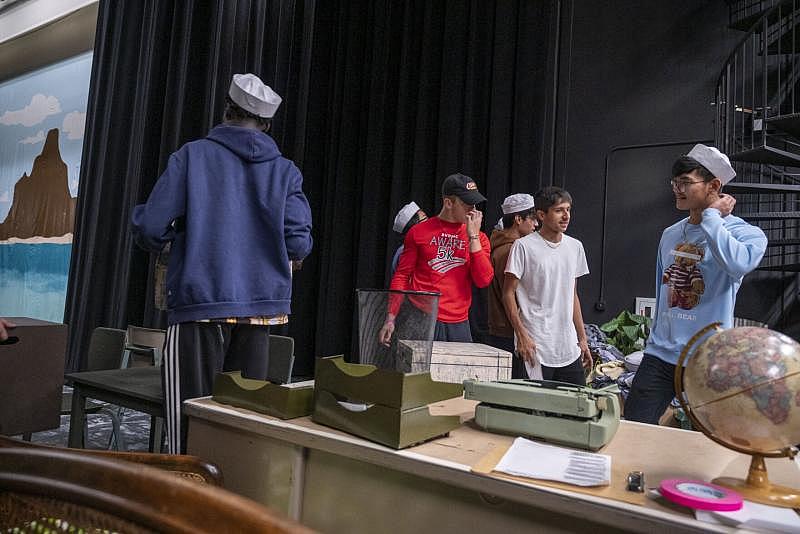

Students at Storm Lake High School rehearse the fall musical, South Pacific. The school district is one of the most diverse in the state of Iowa. Natalie Krebs / IPR

The Storm Lake School District is one of the most diverse in the state. About 87 percent of students are people of color. Most are immigrants, and 57 percent are English language learners.

“I have to be honest, I think this is the hardest start to the school year I've ever seen,” said Stacey Cole, the district’s superintendent.

She said she’s only beginning to see the long-term impact of the pandemic on students and that many are showing signs of extended trauma.

“We know our kids are reporting anxiety, depression -- all of those types of things that you see when people are struggling with their mental health. We are seeing that at a very increased rate,” she said.

Stacey Cole is the superintendent of Storm Lakes school district. She said many students are struggling with mental health issues related to the pandemic. Natalie Krebs / IPR

Cole said the district has invested more into mental health resources, like virtual therapy options, this year.

Meanwhile, public health officials said the pandemic has really highlighted the need for more funding and support for local departments that serve diverse populations, like Buena Vista County.

“I'm not gonna say we're special, but we are special. We have a very diverse community when you look at the rest of the state, and it does take more time and more dollars,” said Julie Sather, who heads the Buena Vista County Health Department.

Sather said the 13-person department could use more resources like interpreters, instead of relying on outside language lines.

But many in Storm Lake say the community ultimately is full of incredibly resilient people.

Julie Sather is the head of the Buena Vista County health department. She took the job in February of this year after the previous head retired. Natalie Krebs / IPR

“I look at immigrants and refugees, and I see resilience and stamina and strength,” said Di Daniels, one of the founding members of SALUD, a community health organization.

“I wonder sometimes this is just one more thing, one more hurdle they have to get over?”

Marroquin, who’s also a member of SALUD, agreed that many immigrants like herself have learned resilience through overcoming many challenges, like starting life in a new country.

“If you have been going through the worst things, adapting to COVID will be something that you find a way,” she said.

This project was produced as part of the 2021 National Fellowship with USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

With support from Hola Iowa with Spanish translations.

[This story was originally published by Iowa Public Radio.]