If Ebola hits again, this state is doing everything right (Part 1)

Anna Almendrala’s reporting on Ebola’s impact on the U.S. was undertaken as a California Health Journalism Fellow at the University of Southern California's Annenberg School of Journalism. This is the first in a three-part series about the different ways the global Ebola outbreak has changed the United States.

Other stories in this series include:

How U.S. hospitals are defending themselves against the next big outbreak (Part 2)

Victor Peacock sits at the Brookdale Library in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota on June 26, 2015.

BROOKLYN CENTER, MN — Victor Peacock’s calm, friendly face is marked by physical scars that hint at his painful history. During Sierra Leone’s Civil War in the '90s, Peacock was captured and tortured before coming to the U.S. as a refugee. Since arriving in Minnesota 14 years ago, he’s become a youth leader in after school programs and holds down steady factory jobs when he can find them. But Sierra Leone is still very much on his mind and in his heart — Peacock calls his family, who are scattered across the coast of West Africa, whenever he can, and sends money home to support his eight siblings.

In July 2014, he found out over the phone that his close friend Kemah Senessie died of Ebola in Sierra Leone, just two days after she had asked Peacock if he could send $50 to help her pay for food.

“When I heard about her passing, I thought, ‘Oh my God. I really want to go to Sierra Leone,'” said Peacock. He'd spent three years of his country's civil war carrying people who were injured on his back and in wheelbarrows, to the gates of the Red Cross, about three miles from his home. How could he sit back now, he wondered, while the people he loved most were in danger again?

Peacock wasn't the only member of Minnesota's large West African community who wanted to return home to help. Others were determined to make the trek to loved ones in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, armed with whatever supplies and training they could piece together. It was an understandable and human reaction to the crisis. But their missions of mercy could've made things much worse, spreading the virus further and potentially bringing more cases to the United States. On July 31, 2014, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued its highest warning against all unnecessary travel to West Africa.

Such warnings have limited effect; public health experts know that people are not compelled to action by listening to an official bulletin from the federal government. Instead, community-driven public health messages resonate far better. In the case of Minnesota, which houses one of the largest Liberian populations in the U.S., this meant counsel from ministers, imams, and leaders of ethnic organizations who acted as safeguards against the compassionate yet dangerous impulse to return home. Together known as the Minnesota African Task Force Against Ebola, this group offered a clear and unified message: Don't go.

'We saw stigma emerging'

“We saw stigma emerging, and we saw people talking about traveling,” remembered Abdullah Kiatamba, one of the main organizers of MATFAE and the executive director of African Immigrant Services in Minneapolis. “Things were getting really out of control."

For instance, a school district asked a student who had traveled to West Africa to stay home from classes until the 21-day disease incubation period had passed, despite the fact that this isn’t medically necessary; the Minnesota Department of Health had to intervene in order to place the child back in the classroom. At town hall-style meetings, community members voiced their fears about West Africans “contaminating” the blood supply, and asked if it was safe for their children to play with the Liberian-American kids next door. In one of the most bizarre cases, MDH received a call from a concerned woman who reported that she saw “a black man with rubber gloves on at the supermarket."

“She wanted us to drive out and get him,” remembered Danushka Wanduragala, a Minnesota Department of Health expert on refugee and immigrant health.

But the state was well positioned to take action against stigma. In July 2014, when the Ebola crisis was beginning to escalate in West Africa, Wanduragala organized an initial meeting with leaders from Liberian, Sierra Leonean and Guinean community groups, churches and mosques, to discuss how to respond. This group eventually came to include officials from Brooklyn Center and Brooklyn Park, two cities north of Minneapolis where most of the state’s West Africans live. Together, they formed MATFAE and turned it into the largest community-based response to Ebola of its kind, funneling critical information and resources not only to West Africans in Minnesota, but to their families abroad.

The task force’s goal was to incorporate official federal guidelines into messages targeted to West Africans, delivered by leaders they could trust in a way that spoke to their lives. Materials were available in French, a lingua franca for West Africans, as well as the state's other major languages: Spanish, Somali and Hmong. Alongside Hennepin County and Minnesota's departments of health, the task force helped organize at least 10 outreach events through mid-November, including vigils for Ebola victims, peer education trainings on how to talk to people about Ebola and informational sessions about how the disease spreads. Attendance ranged from 60 to over 400 participants at these events, and the messaging was tailored specifically to West African immigrants: what to do in the event that a recently-arrived visitor begins experiencing symptoms, for example, or how to support family members without flying there.

"We wanted folks to be aware that if they were going to volunteer and they weren’t aligned with an organization, they might end up getting sick with something else -- malaria -- and then end up getting placed in a waiting area with folks with Ebola," explained Wanduragala.

MATFAE also created an Ebola stigma legal response team and hosted the Department of Justice at a forum to explain what West African immigrants should do if their schools or employees discriminated against them. They delved into lobbying by petitioning Minnesota’s national representatives to vote for President Barack Obama ’ s emergency Ebola funding request, as well as support temporary protected status for recent immigrants from Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone, preventing them from being deported for 18 months. They gave media training to community leaders inundated with requests from national press outlets to comment on the growing outbreak.

And on top of it all, the task force directed the angst and energy of thousands of restless, worried Minnesotans into financial and supply drives, donating more than 20,000 pounds of medical supplies and 12,000 pound of non-perishable food to countries in West Africa.

Before the task force formed, there was no single model in the nation for such an effort. Wanduragala credits MATFAE's success to their deep integration into the community -- it was formed out of 11 different Liberian, Sierra Leonean and Guinean groups and guided by state and county health departments.

“It’s not like we do a forum and expect people to show up,” Wanduragala said. “We needed those cultural liaisons and those connectors to the community to … make it really resonate with the folks that needed to hear it.”

West African community leaders, along with the Hennepin County and Minnesota departments of health, formed the task force July 31, 2014, a full two months before the first case of Ebola was diagnosed in the U.S. To put that in perspective, Dallas County Health and Human Services did not start reaching out to local organizations and community members about Ebola until September 30 -- five days after Thomas Eric Duncan first walked into the emergency room at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital and was mistakenly discharged. He went on to become the first person to be diagnosed with Ebola in the U.S. And in New York, which has the largest West African population in the country, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene would not begin reaching out to its West African communities and ethnic media until October, after Manhattan resident Dr. Craig Spencer returned from a trip to Guinea with Ebola.

Before the task force, Kiatamba said, there was “no messaging and no clarity.”

'So hopeless'

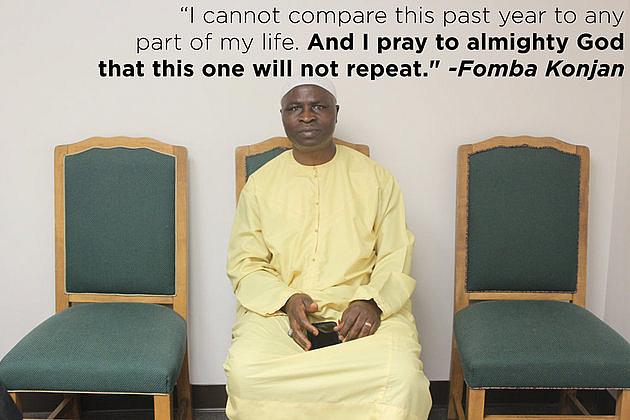

While the decision to stay in Minnesota was clear, that didn't make it easy. Fomba Konjan, a Liberian-American man who lives in North Minneapolis, said he lost 37 family members to Ebola while trying to help them from afar.

ANNA ALMENDRALA Victor Peacock sits at the Brookdale Library in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota on June 26, 2015.

Bendu's children, scared of contracting the virus themselves, left food at the doorway. And when the family was banned from their usual selling spot at the market because word had gotten out about her illness, Bendu stopped speaking, which cut Konjan off from her for good.

“She couldn’t talk anymore — so hopeless,” Konjan said through tears. "After that I could not talk to my sister anymore.” Five days after being turned away from the hospital, he said, Bendu was dead. Now, almost a year later, Konjan still lies awake at night, unable to sleep because of the lost lives that haunt him.

“I cannot compare this past year to any part of my life,” he said. "And I pray to almighty God that this one will not repeat."

Though the task force convinced Konjan and others to stay home, about 25 local residents could not be dissuaded from travel. They were routed to the American Refugee Committee, a group that was recruiting health volunteers for a medical aid trip to West Africa. Peacock resolved to work as much overtime as he could at his factory job, in order to send as much of his paycheck as possible to help relatives and friends back home.

Learning from past mistakes

Minnesota and Hennepin County, specifically, were able to hit the ground running with community outreach because of a disaster that hit Minneapolis back in 2011. After a tornado ripped through the north of the city, displacing hundreds of residents, health officials realized that they were getting fewer than anticipated visits to the resource center for money, tools and other supplies. The problem: They weren’t getting very many requests for help from members of the local Hmong community, whose neighborhoods were hardest hit.

"They weren’t showing up at the community resource center in the numbers we would have expected," said Bill Belknap of Hennepin County Public Health. In response, Belknap and the county teamed up with a local non-profit called ECHO to create a team of volunteers known as the Cultural Services Unit -- a multicultural, multilingual group that could act as a conduit between ethnic groups and county health officials. To prove they were serious, the county rerouted federal money to pay for rigorous training. The volunteers learned communication techniques, water and fire safety and how to take leadership roles in the event of an emergency.

By chance, they set up their first ever unit of 14 original volunteers in Brooklyn Center, the city that's home to most of the county’s West African residents. When Ebola death counts started rising in the summer of 2014, these CSU volunteers became crucial in the campaign to reach out to Minnesotans about the disease.

"We didn’t have to figure out whom to deputize, so to speak," explained Belknap. "They already were identified, trained and on a call-up system." For instance, 23 CSU volunteers became certified peer educators on the subject of Ebola. Representing the county at task force events, they spoke at meetings, staffed health information tables, and helped direct people to county services.

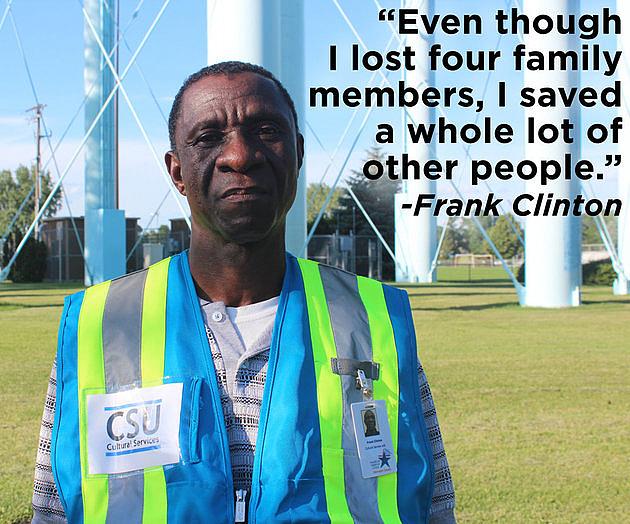

Frank Clinton volunteers at the Earle Brown Days community parade in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota on June 25, 2015.

Their impact wasn’t just local. Frank Clinton, a Liberian-American who has lived in Brooklyn Center since 1999, was a CSU volunteer, and felt that he had a hand in saving many lives back home because of his outreach work. Literacy rates are low and mistrust of the government is high in Liberia, so reporting health information back to his relatives via telephone -- simple things like the importance of hand washing, refraining from unnecessary physical contact, and even the basics of how the disease spreads -- played a crucial role in keeping his family safe, said Clinton.

“Even though it was in line with what the Liberian government was telling them, it also helped them to say, ‘Ok, I think we are getting enough education on this thing,'” said Clinton. “Even though I lost four family members, I saved a whole lot of other people.”

Since its inception in 2013, the CSU model has spread to Minneapolis, Brooklyn Park and Eden Prairie, three other cities in Hennepin County. And it’s a blueprint for community preparedness that Wanduragala, the Minnesota Department of Health worker who organized the first Ebola task force meeting, says should be emulated across the nation.

"I think it’s a model that other counties and other states should really be using, too," said Wanduragala. "Folks aren’t putting money into something like this. Doing that early on with Brooklyn Center was so integral to the Ebola response."

Minnesota's early outreach helped other health departments, like those in Colorado and Rhode Island, align quickly on initiatives including outreach and French translation. Dr. Michael Fine was director of the Rhode Island Department of Health during the Ebola outbreak, and he has no doubt that early outreach efforts helped protect his state in the event that they might catch a case. He advises every state and local health department to reach out to as many different ethnic communities as they can within their regions.

"As people in our communities began to function as trusted sources for their families at home, they thought about and understood the messaging,” Fine said. "That made our communities here very well prepared to deal with a case, should we have had one.”

The story was different in Texas, where the first Ebola patient in the U.S. was treated and died and where the first U.S.-acquired Ebola infections occurred. Dallas County’s Ebola coordination with local health providers began in July of 2014, but outreach to local organizations and community members didn’t begin until September 30 -- the day Duncan’s Ebola diagnosis was confirmed.

No public health experts were willing to speculate if Duncan’s outcome would have been any different had it happened in Minnesota, and Dr. Melinda Moore, a public health researcher specializing in public preparedness and infectious diseases at Rand, said it would be “unfair” to expect other states -- even ones with large West African populations -- to be as prepared.

“It’s probably unfair to have expected other counties to have organized something as well and as good and as strong as that county in Minnesota did, in advance of a case,” said Moore. Yet her 20-year tenure at the CDC made her very well acquainted with the Minnesota Department of Health and its reputation for excellence, and she says it's no surprise that the state was so prepared.

She praised Minnesota for putting the “public” back in public health and said it stood as an example for other counties and states across the U.S.

“It’s a very good example of really harnessing the power of the people for their own good,” said Moore. "I think its something that at least other counties all around should be aware of.”

'Suppose I go and get a fever'

Because of the strong messaging from MATFAE and others in his community, Peacock realized that going to Sierra Leone would be dangerous and counterproductive.

“Suppose I go and get a fever,” Peacock mused. "Even if I could go there in person, what would I do? I’m not in the health field."

The best thing he could do for his friends and family in West Africa, he realized, would be to help support them as their countries descended into the outbreak. From June 2014 to March 2015, he estimates that he sent 75 percent of his paycheck -- about $200 to $300 -- to various friends and relatives in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

The money went to help his loved ones remain safe and well-stocked while they stayed home from work and school and couldn’t earn money of their own. He remembers instructing them to use the funds to hire taxis and shop in supermarkets, as opposed to walking to open-air markets. He remembers begging bosses at the medical device factory where he worked in Brooklyn Center for any overtime hours they could spare.

“I’m not a person who eats that much,” said Peacock. "My concern was how to save lives over there.” Once again, he'd carried countless people on his back: not only the friends and family who received his financial gifts in West Africa, but their neighbors, who knew they could always count on Peacock’s well-supported clan for a plastic baggie of stew and rice if they hit dire straits.

In April, Peacock lost his job at the factory, and he’s just beginning to reflect on the past year. After months of harrowing news and emotional, tear-filled phone calls with his family -- he lost 20 loved ones, five of whom were family members -- he wants to go back Sierra Leone in December, this time to help the country rebuild.

“Financially, I don’t have it,” Peacock said about airline tickets, which can cost almost $2,000. “But I just want to go there, embrace them, talk to them, and go around and see what I can do.”

[This story was originally published by The Huffington Post. Photos by Anna Almendrala.]