Kalihi Has The Worst COVID-19 Outbreak In Hawaii. Here’s How The Community Is Responding

This article is part of a larger project by Anita Hofschneider, produced with support from the 2020 National Fellowship and a grant from the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Her other stories include:

Community Leaders: State Is Failing Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 1: Hawaii Wanted To Save Insurance Money. People Died

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 2: Health Officials Knew COVID-19 Would Hit Pacific Islanders Hard. The State Still Fell Short

Hawaii Researchers: State Must Support Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Pacific Islanders Have The Highest COVID-19 Death Rate In Hawaii

Women Were Already Struggling At Work. The Pandemic Is Making It Worse

Here’s What Honolulu Is Doing To Test Hard-Hit Communities For COVID-19

Hawaii COVID-19 Data For Race And Ethnicity Is Missing

Hawaii Pacific Islanders Are Twice As Likely To Be Hospitalized For COVID-19

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 3: Pacific Islanders Can’t Return Home During COVID-19 — Even To Bury Their Loved Ones

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 4: The Pandemic Is Hitting Hawaii’s Filipino Community Hard

Before COVID-19 started spreading in Hawaii, kids worked on their bikes at KVIBE in Kalihi. The bike shop became a food hub when the pandemic hit.

The KVIBE bike shop in Kalihi is normally packed with kids. The warehouse along Kamehameha IV Road is walking distance from multiple public housing complexes, and the organization takes seriously its mission to help mentor kids and get them off the streets.

But when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the warehouse transformed.

“We turned our shop into a food hub,” explains Josh Kim, who works at the youth outreach bike shop that’s part of the Kokua Kalihi Valley Comprehensive Health Center.

By late May, more than 21% of Kalihi residents had filed for unemployment and others were still struggling to do so. KVIBE partnered with the YMCA of Kalihi to give out up to 150 meals per day to families in need. Six months into the pandemic, Kim and other staff spend their days delivering food throughout the neighborhood.

The pivot was a necessity in Kalihi, where the pandemic has hit harder than every other part of the state. State data shows the 96819 zip code reported 1,396 total cases thus far, the highest of any zip code in the state. Nearly two-thirds were identified in the last 28 days.

That’s 261 cases per 10,000 people, more than twice the islandwide rate. And it’s worsening — in August, about 30% of Kokua Kalihi Valley patients who got tested for coronavirus received positive test results.

“Our community is in crisis right now and we are doing our best to come together,” said Puni Jackson, a KKV staffer.

Puni Jackson says the story of COVID-19 disparities is the story of Kalihi.

Kalihi has long been home to many recent immigrants from the Philippines and Oceania. Non-Hawaiian Pacific Islanders make up 31% of Hawaii coronavirus cases, compared with just 4% of the population. Both Pacific Islanders and Filipinos are disproportionately dying from coronavirus in Hawaii.

But Jackson said while media coverage about the pandemic has often focused on high rates among ethnic groups, that data doesn’t tell the full story.

“It really is about Kalihi,” Jackson said. “Every new wave of people that comes into this place struggles.”

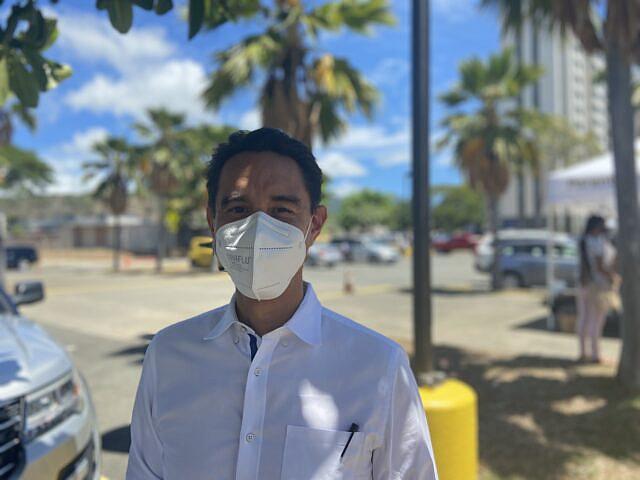

Councilman Joey Manahan, a Filipino immigrant himself, has been anxiously watching the pandemic worsen in his district.

“I just saw the numbers going up in 96819,” he said. “There’s got to be a reason for that.”

Councilman Joey Manahan is glad to see more testing in Kalihi. He is pictured on a day of COVID-19 testing at KPT.

He thinks the fact that many families live in dense, multi-generational households in Kalihi is contributing to COVID-19’s spread.

“Because they don’t have the space to quarantine properly, I’m hearing the numbers are going up every day,” he said.

Access to testing is also a concern. It’s hard to make time to get tested when you’re working multiple jobs, he explains. Or if you’ve lost your job, you might be afraid of how much testing could cost, he said.

The city has been offering free testing in the district this month as part of a statewide surge-testing effort. But once they test positive, people have struggled to figure out what to do once they get sick, even though the state has been trying to improve outreach to patients.

“People are left in the dark having to fend for themselves not really knowing what to do,” Manahan said. “People are not necessarily getting the information that they need. They don’t want to violate stay-at-home orders. They don’t want to make anyone sick but they are also going hungry.”

During the first stay-at-home order, Kalihi residents were more likely to get arrested for violations than other Honolulu residents, according to a Hawaii Public Radio analysis.

Pivoting To Food Delivery

Even before the pandemic, the community faced health challenges. In some parts of Kalihi, life expectancy is 76 years on average, compared with 82 years island-wide.

But the health impacts of the pandemic are nearly inseparable from the economic impacts, as statewide shutdowns cause massive job losses in the hospitality and service industries. And service providers say that’s driving up hunger.

Individuals and community organizations are pivoting their missions to try and meet that need.

Every weekday, a line of vans deep in Kalihi Valley gets ready to drop off food and supplies to COVID-19 patients, kupuna and others who are stuck at home due to the pandemic. They leave from Hooulu Aina, a 100-acre nature preserve managed by the KKV community health center. Normally, the valley hosts weekly and monthly gatherings of volunteers who work on growing local food. That’s all been canceled since the pandemic hit.

At Ho’oulu ‘Aina, vans line up to deliver food to families in need. More than 21% of Kalihi residents had filed for unemployment by May.

Megan Inada, a staffer at KKV, said the pandemic has upended traditional job titles and forced everyone at the clinic to shift jobs. Inada’s official title is researcher – now, she often spends mornings sifting through new data about positive coronavirus cases and fielding calls from patients.

At Hooulu Aina, a conference room morphed into a mini-headquarters for emergency planning and then a storage room stocked with food and water from Costco, Sam’s Club and local donors. The food deliveries are necessary as the Department of Health has struggled to help COVID-19 patients quickly and hunger needs have ballooned. Since June 19 KKV has delivered food to about 200 COVID-19 positive households, or more than an estimated 1,000 people.

A list of food that will be delivered to families in Kalihi. At Hooulu Aina, a conference room has been transformed into a storage room for food to feed sick families in the pandemic.

Across Kalihi, churches and community groups are mobilizing. Service providers at We Are Oceania are helping Pacific Islanders access health insurance and unemployment. Hawaii Cedar Church has been distributing food to homeless people. Every Saturday, Coronacare Hawaii has been giving out local produce in Kalihi.

Even advocates who normally don’t live or work in Kalihi are responding to the need. David Tautofi is a Kaimuki High School football coach who grew up in Palolo public housing. He runs a youth development organization and has been partnering with other groups to deliver food.

On Friday, he went with volunteers from Altres, Ham Produce and Seafood and Chef Hui to Kuhio Park Terrace to give out milk, bread and other staples, but noticed that people seemed wary about picking it up. He thought perhaps because it’s the beginning of the month, people might have food stamps and need less food. But after talking to the group of advocates who helped with food distribution, he realized that wasn’t the full story.

“We’re seeing firsthand the real fear of the COVID among Kalihi families, especially those in the projects,” he said.

He sensed that people wanted the food but were wary of picking it up, fearful of being in the elevator and getting close to strangers. They’re thinking about doing door-to-door distribution when they go back Friday.

“There’s not enough resources going to Kalihi, especially the housing projects throughout Honolulu, and I just feel like there’s not enough urgency for that,” Tautofi said.

Resiliency

Shifting to meeting the needs of COVID-19 patients and other Kalihi families is fulfilling for many advocates. But it comes with emotional and physical costs.

“Everyone is doing five different jobs,” said Inada at KKV. The worst part of the 60-hour workweeks is not being able to spend time with her son.

By this point in the pandemic, some community health center staffers are getting sick, and are going home to crowded homes just like their patients. Many of them know someone who has died of the virus, according to Dr. David Derauf, executive director of KKV.

Megan Inada is a researcher at KKV but now spends her days helping to coordinate COVID-19 patients’ needs.