Korean American Seniors Prepare for Death with Living Wills

The story was co-published with Korea Daily as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Korean American seniors listen to a seminar on wellness, including filling out advance directives, at Dream Church in Pasadena on Oct. 27.

By Hyoungjae Kim

At noon on October 27, more than 30 Korean American seniors in their 60s and 90s gathered at Dream Church in Pasadena for a special seminar. Julie Park, director of education, and Hanmi Jung, a lecturer from the nonprofit organization Somang (Hope) Society, spoke on the topic of “Preparing for life, not death."

For 17 years, Somang Society has been holding “Well-Dying” educational seminars at senior organizations, institutions, and churches in the Korean community. The idea is to help seniors take care of their physical and mental health so that they can prepare themselves for the last moments of their lives.

The seminar was divided into two parts, one on how to diagnose and cope with dementia and the other on "Advance Healthcare Directive," also known as a living will. “If you prepare for life-sustaining treatment in advance, you can eliminate the fear of death. If you do not prepare yourself, you may face various difficulties such as meaningless prolongation of life against your wishes when you are unconscious due to dementia or other conditions.”

The seniors who attended the seminar seemed open minded and eager to listen to the topics addressed. Most of them acknowledged the importance of preparing for a good death and realized that this preparation could quell their worries and stress about dying.

“The older I get, the more I want to know how to prepare for my own death,” said senior Park Kyung-ran (75). ”My brother died suddenly of a brain stroke when he was 65. He had prepared for his death in advance, including donating his body, and seeing him do it according to his wishes made me realize that I should also prepare. I'm scared when I think about death, but I want to deal with it wisely and not be afraid,” she said.

Do not hesitate to talk about death

Preparing for death is often seen as a foreign concept. “Eastern cultures, like Korean Americans, emphasize life in this world rather than the afterlife, so it’s not common to see people trying to prepare for death in advance,” said Sun Chul Hwang, CEO of Hansol Insurance.

Somang Society’s “Well Being, Well Aging, and Well Dying” campaign aims to create a “beautiful life and a beautiful end.” Dementia diagnosis and coping, advance directives, and body donation pledges are among the most important activities. The senior-led organization emphasizes the need for seniors to be aware of their physical and mental health and to prepare for death in a way that brings emotional stability.

“In Korean culture, it’s taboo to talk about death,” says Boon Ja Yoo, 89, president of the Somang Society. ”We need to take the topic of death out for serious communication. If you don’t do that and you die suddenly, everyone, including your family, will mostly panic.”

Preparing seniors for their own deaths has been shown to have positive mental health benefits.

Young Hwa Choi, a senior community health worker at the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, said, “There is a lot of negativity about death in the Korean-American community,” and added, “Positive thoughts and attitudes about death can be important for senior mental health and well-being, giving them a more positive outlook on life and the opportunity to make each day count.”

“It can also help overcome feelings of "getting old and useless," and it can lead to more fulfilling relationships with loved ones.”

This project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.

In traditional Korean culture, seniors are expected to have a strong sense of filial piety and to be cared for by their families even in old age. As a result, it is considered disloyal for children and parents to discuss how to deal with illness or prepare for death. Most seniors expect that their children and other family members will take care of their illness or death.

However, in the Korean immigrant community, families often live apart and seniors are often left to fend for themselves. This can lead to loneliness and fear of medical treatment and death.

One study, conducted in 2022 with a cross-sectional sample of 2,150 older Korean immigrants in the U.S. found that Korean seniors aged 60 and older reported high rates of psychological distress due to isolation from family and society during immigration.

Somang Society urges Korean seniors to respond wisely to the realities of their situation. The more proactive seniors are in preparing for illness and death, they emphasize, the more they can take care of their mental health.

The effectiveness of the “Well-being, Well-Aging, Well-Dying” campaign has been proven by the numbers. As of November 2024, a total of 18,000 Korean seniors had completed advance directives in the past 17 years.

Of these, 2,600 have pledged to donate their bodies. Eighty-nine have already donated their bodies to the UC Irvine School of Medicine to help train the next generation of doctors and advance medicine.

Over the past 17 years, Korean seniors have led the Well-Dying Campaign, and a total of 18,000 people have signed advance directives, and 1,800 have pledged to donate their bodies for medical advancement and social contribution.

Courtesy of Somang Society

Body donation is a rewarding social contribution

In Korea, people have traditionally shunned body donation, believing that the body is a source of dignity and pride. In recent years, the first generation of Korean immigrants have been breaking away from traditional ideas. They want to contribute to social causes, such as medical advancement, and have even begun practicing body donation.

On Nov. 2, a body donation memorial service was held at Grace Korean Church in Orange County, co-sponsored by UC Irvine School of Medicine, the hospital, and the Somang Society. The Well Dying Advance Directive Campaign, led by Korean-American seniors, has resulted in 1,800 voluntary body donation pledges.

“The number of Korean seniors who understood the campaign and wanted to do something good for American society in the event of their deaths has increased,” said Yoo Bun-ja, president of the Somang Society. ”Currently, about 60 percent of all bodies donated to the UC Irvine School of Medicine are Korean-American, which is amazing.”

In a survey of 1,792 Korean seniors (40% male, 60% female) who pledged to donate their bodies to the Somang Society, 69% of respondents said they wanted to contribute to American society. This was followed by 8% to avoid financial burdens on their children, 5% to simplify funeral arrangements, and 3% because they have no family.

Senior Park Joon-koo (90), who completed an advance directive that included a body donation pledge, said, “Body donation gives novice doctors a chance to practice dissection, and in the end, everyone benefits.” “Preparing for my own death in my 60s and growing old gave me peace of mind and made me feel incredibly comfortable. I lost my fear of death. Now my son and a friend have also taken the pledge to donate their bodies,” he laughed.

Lonely deaths and dignified goodbyes, Korean-American seniors confront ‘end-of-life’ preparedness

A lonely funeral for a Korean-American elderly man was held at Dae Han Mortuary in Koreatown.

A Korean-American man in his 70s died suddenly after losing contact with his family. A church pastor who knew him searched for his family but could not find them. With the help of the pastor, the body was given a simple funeral and cremation.

According to the professionals in the industry, more Korean-American elders die alone than one might think, most of whom pass away suddenly and without preparation. Many of them are men in their 60s and 70s, mostly alone in senior apartments and rented houses.

The reasons behind Korean-American loner deaths are often mental health problems such as addiction. Most of these lonely deaths leave behind destroyed homes.

“We hold funerals for about seven to eight lonely Korean Americans a year,” said Michael Lee, CEO of the Dae Han Mortuary. “Some of them pass away empty-handed. They suffer from mental health problems such as alcoholism and gambling addiction, and a lot of them are abandoned by their families.”

Lee, who has seen many deaths as a funeral director, emphasizes “preparing to die”. “When I’m asked to speak at churches and other places, I tell them, ‘You should always be prepared when around your 80s,’” he said. “Making a will while you’re still alive and planning for even minimal funeral expenses ($1,700 to $4,000) can prevent family feuds after the funeral.”

Dying with dignity, your preparation and choice

To promote “well-dying” awareness, The Somang Society has been campaigning for people to complete an Advanced Healthcare Directive.

The idea is for people to decide how they want to die, with dignity.

An Advanced Healthcare Directive is a document that seniors sign that sets out their "pre-death medical decisions’" and "post-death funeral decisions." It is legally binding upon signing but can be revised while you are still conscious before you die.

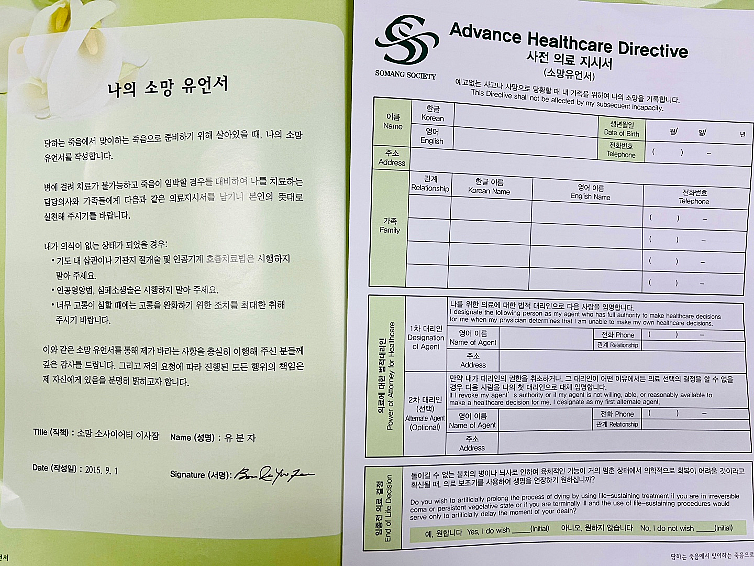

Advance Healthcare Directive form and stating the wishes of the President Yoo of the Hope Society to discontinue life-sustaining treatment.

The advance directive is a yes or no answer to the question, “If I am physically incapacitated due to an irreversible, terminal illness or brain death, and I am certain that medical recovery is unlikely, do I want medical assistance to prolong my life (such as intubation, bronchotomy, ventilator treatment, artificial nutrition, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, etc.”

For funeral decisions after death, you can list the funeral arrangements (organ donation, burial, cremation, body donation, and others), funeral director, or body donation organization.

To be legally enforceable, the advance directive must also be signed by the person stating their wishes and signed by two witnesses.

“The ability to decide how they want to die is linked to ‘human dignity,’” says Hye Won Shin, Director of Asian American Community Outreach of the UC Irvine Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders (UCI MIND). “Without an advance directive, if you lose consciousness due to serious illness or other conditions, you may be forced to receive treatment you don’t want until you die.”

“Instead of fearing death, people who have completed an advance directive express satisfaction that ‘I can end my life the way I want to end it,’ and they say they have left the best gift to their children, especially as it relieves them of burdens such as guilt,” Shin added.

The well-dying campaign also requires a proactive approach. Choi said “Emphasizing well-dying to seniors who are unprepared for the idea of death can lead to rejection, anxiety, and trauma. It is also important to ask for informed consent when conducting seminars about death.”