L.A. County gave up on a mental health program — and is handing back millions in grants

This project was originally published in Los Angeles Times with support from our 2022 Data Fellowship.

Delcia Calderon, left, speaks with Luwin Kwan, a licensed mental health professional, in her Los Angeles apartment. A mobile crisis team was dispatched to help her adult son, who appeared to be in emotional distress.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

It seemed like any other night. Silverio Lujan’s teenage daughter was distant and listless. Then, before he knew it, she had a fistful of pills and a knife in her hand and threatened to end her life.

Panic-stricken, he dialed 911.

After an evaluation, an intensive-care team from a local nonprofit quickly intervened with Lujan, 34, and his 13-year-old daughter. For three months after the February episode, the team wrapped itself into the lives of the South L.A. family. Both father and daughter received therapy.

They’re still working on their problems, but the crisis has passed.

Therapy allowed his daughter “to change and get closer to the family, and want to learn things and keep fighting for what she wants — for the dreams she has,” Lujan said in Spanish.

But the program Lujan credits with rescuing his daughter from suicidal depression has now closed. His family was among the last to be served by it.

Staff members at Children’s Institute in Los Angeles are reflected in a picture frame as they discuss the closure of a mental health program dedicated to linking vulnerable people to care.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Providers insist that what are known as child and adult outreach triage teams were saving some of L.A. County’s sickest residents by closing a gap in care.

Officials with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, however, said they were underwhelmed by the teams’ performance.

The program was funded with a pair of state grants totaling roughly $30 million — money from the tax on millionaires levied by the voter-passed Mental Health Services Act. The grants expired in June. The county declined to use its own funds to continue the services. By the time the programs sunsetted, the county had spent only about half the state funds, according to preliminary figures. An estimated $15 million will be returned to the state.

That large pot of unspent money represents a “major bungle,” said Dr. Jonathan Goldfinger, a pediatrician who previously co-chaired the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health’s alternative crisis response initiative.

Goldfinger described what he called a history of foot-dragging within the mental health department, often driven by internal politics related to staffing.

“What human being would have [that much money] to serve suffering people and give it away? That’s unconscionable to me as a physician, as a public health professional, as a human being,” said Goldfinger, the former chief executive of Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services who is now a consultant for physical and behavioral healthcare systems.

Spending dollars can be hard and slow, and counties are afraid of continuing financial commitments — in part because of the boom-and-bust nature of California’s public revenue streams, said Alex Briscoe, former director of the Alameda County Health Care Services Agency, who now serves as principal for California Children’s Trust, a policy advocacy group.

Los Angeles police were called in to assist a mobile crisis team staffed with mental health professionals as they responded to a man who was in the midst of emotional distress.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

The dispute over how L.A. handled the triage teams highlights how counties in California fund mental health services, which frequently involves new ideas being funded temporarily then abandoned as county leaders fail to come up with plans to sustain them before the money dries up.

That system might soon be remade. Gov. Gavin Newsom recently proposed overhauling a vital funding source for local mental health departments. Some stakeholders see the move as a rebuke of how the money generated by the Mental Health Services Act is being handled by county governments and the commission that oversees the funds.

As homelessness and mental health crises overwhelm local systems, the governor is proposing to shift resources to address an urgent need: beds for people struggling with severe psychiatric and substance abuse problems.

Given that resources are limited, that greater emphasis on housing and treatment for the severely ill will almost certainly mean less money for prevention programs, said Briscoe — like the triage teams.

“For a lot of [what] I care about — prevention, kids — it’s going to be bad,” Briscoe said, “but I totally understand how we got here.”

Los Angeles got the grants to start the triage program in 2018, but didn’t launch it until late 2020. The county intended at first to provide the services directly, but opted to contract the work out.

The triage teams were created to prevent people rocked by emotional turmoil from landing in the hospital or jail. The idea was to support people in their moment of urgent need and then help them connect to longer-term services.

To do this, a trio of mental health professionals would enter an individual’s world, meeting them where they were — which was often a street corner or their living room. Then they’d embark together on the journey of accessing care in an often-opaque system, with team members holding them — and often their families — as they languished on waitlists that could stretch months.

“We were out in the streets during the day with them, and working with them, and talking to them, and so they knew there was somebody out in the world that was thinking about them — so there were less calls in the middle of the night,” said Dee Dee Hitchcock, who oversaw the teams for the nonprofit Children’s Institute, one of six providers with which the county contracted.

Over her nearly 23-year tenure she’s seen innumerable pilot programs come and go, but said she thought this one would last.

“This one — this one was something special,” Hitchcock said.

County officials have sought to bolster mental health crisis services in recent years, spurred in part by a federal mandate. Last July, a national mental health hotline known as 988 went live, kicking off an effort to develop a new emergency response tailored for people in emotional distress.

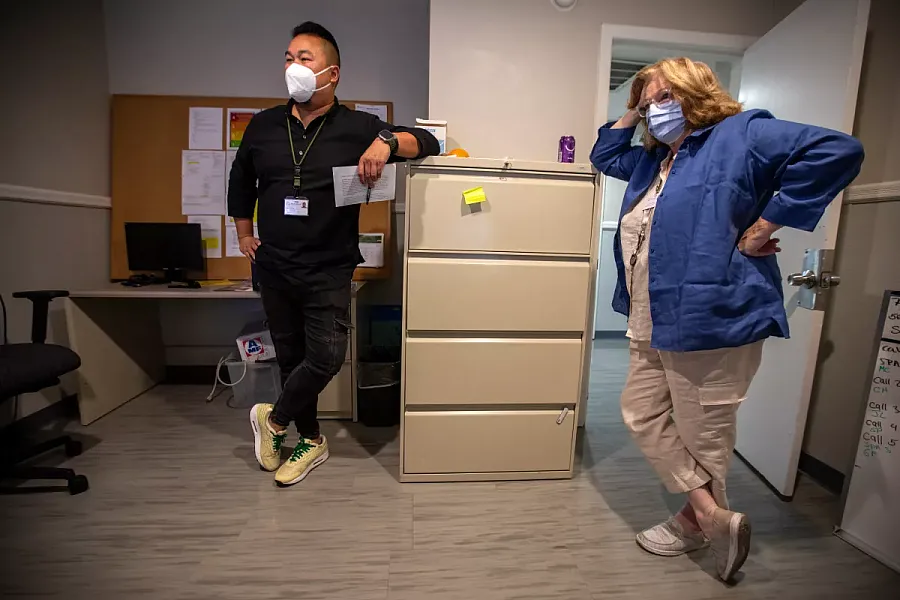

Luwin Kwan, left, a licensed clinician, and Suzanne Dewalt, a peer support specialist, at Sycamores in Altadena as they wait to get sent out on a crisis call to assist people dealing with mental health issues.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Many of those services — such as crisis phone counseling and mobile teams — are reactive: waiting for the fire to start and then rushing to extinguish it, Hitchcock said. By contrast, the triage teams aimed to prevent.

Other programs are “not proactively caring for them in the community and proactively knitting their safety net,” Hitchcock said. “That is a big missing piece.”

Josefina Cignale, a former caseworker with the program, recalls one client, a middle-aged man who endured a lifetime of trauma, who told team members that he had repeatedly thought of suicide as he walked roughly four miles to the Children’s Institute’s campus in Westlake, just west of downtown Los Angeles.

“‘Should I jump off this bridge? Should I walk into traffic?’ The whole way, that’s what he was thinking. But the reason he didn’t, he said, ‘Well, I had an appointment with you. And I had to keep it,’” Cignale said.

But Jennifer Hallman, alternative crisis response manager for the mental health department, said department officials weren’t impressed with the number of adults and children the triage teams connected to services.

Of adults who were referred to the program in the 2021 fiscal year, a little over 15% were linked to new mental health services, with the figure rising to 33.5% for children, according to the mental health department.

“We really saw that the program needs a better way of engaging with that individual afterwards,” Hallman said.

Martine Singer, the president and chief executive of the Children’s Institute, questions the validity of that measurement.

Many people referred to the program couldn’t be reached at all. Severely mentally ill adults living on the streets could be particularly hard to locate, providers said, while children tend to have a more engaged caregiver to facilitate the connection.

In October, knowing that the deadline to spend the grant money was nearing, Singer wrote to the county Department of Mental Health to ask it to sustain the programs after the state money ran out.

Lisa H. Wong, who is now the department’s director, replied that the situation with the teams was “complicated” but that she would consider the proposal.

By February, the providers still had no answer about whether the program would continue. Singer shot off an email highlighting the urgency and then another 10 days later.

Without the programs, “it’s hard to imagine what will happen to all the people that we are helping, particularly the mentally ill adults,” Singer wrote in a Feb. 11 email. “Let’s not return to a world where those who need it the most fall through the cracks in a broken system.”

In March, the answer came: The county stopped referring children and adults to the triage programs, a step toward sunsetting them.

Officials with the county mental health department and providers differ over why the county left so much money on the table.

Mental health department officials said difficulties hiring and retaining staff made it difficult to ramp the programs up quickly.

Top staffers with two of the contracted providers did not identify hiring as a problem. Instead, they say, the department did not allow them to receive referrals from a wide variety of sources — including schools, hospitals and police departments — which would have greatly expanded the number of people they could help.

The department confirmed that it limited referrals, citing grant requirements, but did not provide a detailed response to questions about the nature of the requirements.

County mental health department officials said they sought to extend the grants in January. The state, which had already stretched the grants from three to 4½ years, declined to extend them further.

The county could have kept the programs afloat using another funding source, according to the state Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission.

“We hope that counties made good use of those dollars, and that that good use is reflected in the fact that they’re willing to sustain it with their money,” Commissioner Toby Ewing said.

The county now says it hopes to provide similar services using its existing mobile crisis response teams.

Staff members at Children’s Institute in Los Angeles discuss the closure of the mental health triage teams they ran.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

“Although the grant is ending, the county is committed to ensuring these critical efforts continue, and these essential follow-up and linkage services will be incorporated into our mobile response teams and alternative crisis response efforts,” Los Angeles County Supervisor Hilda L. Solis said in a statement.

“This will allow us to take advantage of other state and federal funding to support these services, and will augment my efforts to expand housing and services throughout the county.”

A Times investigation earlier this year found those mobile crisis teams have struggled to expand, leaving people in dire need to wait hours for help. More than a third of the time in 2022, teams took more than eight hours to respond to crisis calls.

Connecting people to care can be a herculean feat; it’s unclear how the responsibility will be absorbed by the teams.