Lax on lead: How California fails to regulate gun ranges that leave toxic waste in their wake

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s California Impact Fund.

Creatas Video+ / Getty Images

Each time a gun fires a lead bullet, fragments and dust of the toxic heavy metal become airborne. With state-of-the-art ventilation and proper cleaning, an indoor gun range can operate safely. But many indoor ranges in California have failed to do so, poisoning employees, endangering patrons and releasing hazardous amounts of the neurotoxin into the environment.

In June 2017, California health and safety officials acting on a tip from a concerned parent called up the Facebook page of a gun range in Grass Valley (Nevada County) operated by a local Boy Scout leader.

They found photos of about a dozen boys, some as young as 11, garbed in various pieces of ill-fitting protective equipment and inadequate masks, sifting through mounds of sand to dig out bits of spent ammunition: fragments of toxic lead left from rounds fired by patrons. Some Scouts’ uncovered shoes were immersed in the contaminated sand. Only specially trained and outfitted adult workers are allowed to do this job, according to state and federal laws.

Members of Boy Scout Troop 232 in Grass Valley (Nevada County) use sifters at the Range, troop leader Jerod Johnson's indoor gun range in Grass Valley, in 2017, separating lead fragments embedded in sand used to absorb bullets fired at the range. Such hazardous work is supposed to be done by specially trained and outfitted adults.California Department of Public Health

The discovery of “lead mining” at the Range, owned by Boy Scout troop leader Jerod Johnson, should have prompted immediate action by state and county health authorities, several public health experts told The Chronicle.

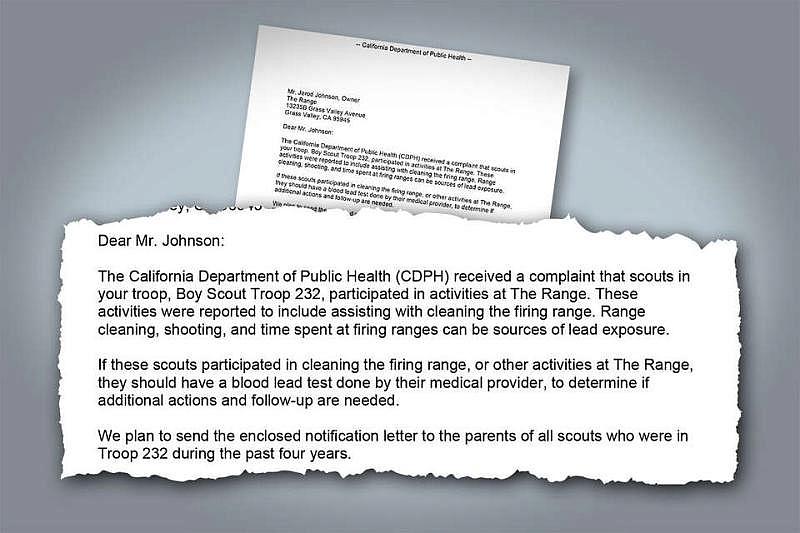

But records obtained through public information requests from Nevada County and the California Department of Public Health show that for two months, no action was taken. And when state health officials finally spoke with Johnson, they apparently made no attempt to identify Scouts in the photos, and didn’t inform troop parents at the time that their children had been exposed to high concentrations of lead, a neurotoxin. High enough, lead-poisoning experts told The Chronicle, that the lead could have poisoned or even killed them had their makeshift personal protective equipment failed.

Johnson confirmed that his troop had done this numerous times, and said he’d used the proceeds from recycling the lead — tens of thousands of dollars — to pay for troop activities.

Still, Nevada County, in consultation with CDPH, waited six months to send a letter to Scouts’ parents, and did so only after allowing Johnson to change the letter so it downplayed the need for medical attention, records show. The delay meant a crucial two-month window to effectively test the youngsters’ blood for lead poisoning had passed. The effects of lead can last for a lifetime, but signs of its presence in blood tests dissipate substantially over time.

A handwritten letter from a concerned parent tipped the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) to the Boy Scouts’ lead mining activities at the Range.

Ultimately, Johnson was ordered by Nevada County officials and the state to “cease and desist” using children in lead-mining operations and to clean up excessive lead that state health department inspectors found inside and outside the range. As recently as April 2021, however, nearly four years after the 2017 inspection, officials again found issues with the Range’s lead management and safety methods and imposed a $485 fine. Results of an April 2022 inspection prompted by a report of a lead-poisoned employee there are pending.

But Johnson was never fined or criminally charged for knowingly exposing children to lead, and his range continues to operate. Johnson remained a Scout leader until at least 2019. Boy Scouts of America did not respond to questions about whether he is still active.

The incident involving the Scouts is just one of dozens at indoor gun ranges in California where clear-cut lead hazards drew minimal response by health and safety authorities, a months-long investigation by The Chronicle and the University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism revealed.

Several public agencies are charged with overseeing the safety of the estimated 200 indoor gun ranges in California. Besides the Department of Public Health, the state’s Department of Toxic Substances Control, worker protection agency Cal/OSHA, and various county-level and regional environmental agencies regulate health hazards and their impacts on individuals and communities.

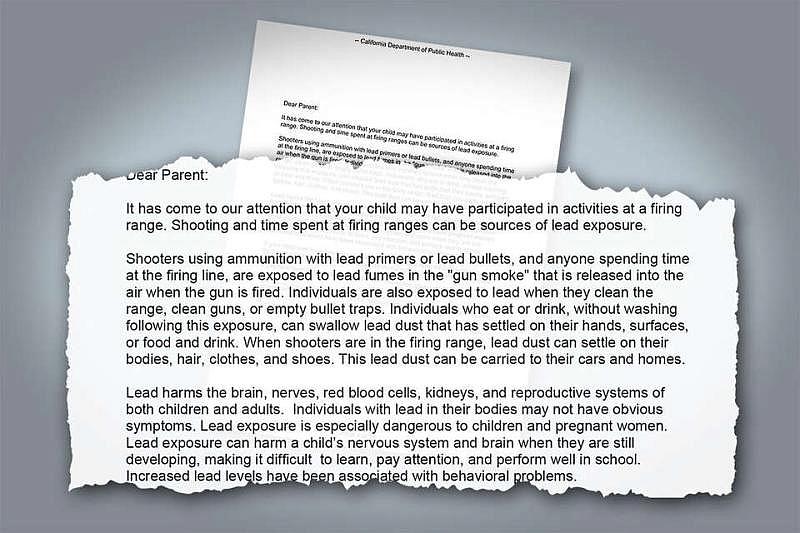

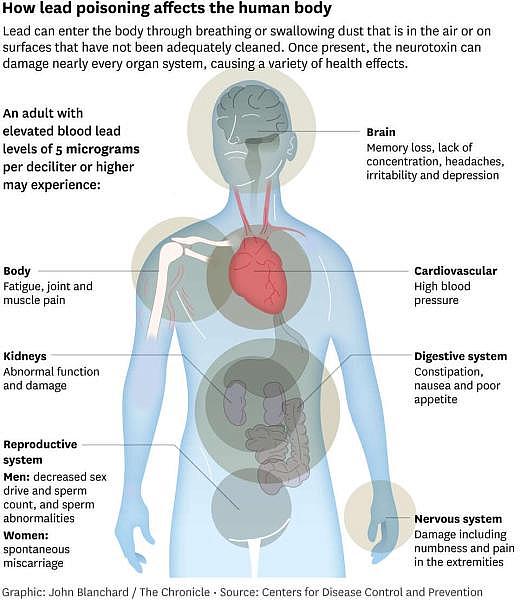

In the case of lead, such scrutiny is crucial. Lead poisoning can attack the reproductive, central nervous and cardiovascular systems in adults and harm children by eroding IQ and causing permanent developmental delay.

But gun ranges known to be exposing clients and the nearby environment to potentially harmful levels of lead have operated nearly free of meaningful regulation, documents from over a two-decade span reveal. CDPH health data shows hundreds of lead-poisoning cases tied directly to gun ranges, as well as exposure to unsafe levels of lead by hundreds of thousands of people who have visited ranges or lived near them.

Meanwhile, the public has largely been left in the dark: The Grass Valley incident, for one, would almost certainly have remained unknown to the public had it not been discovered by The Chronicle and the USC Annenberg Center through disclosures under the California Public Records Act.

Bill Allayaud, the California director of government affairs for the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit organization that has helped pass laws aimed at protecting Californians from lead poisoning, called the situation “untenable” and called for decisive action.

“The Legislature should hold an oversight hearing, call in the agencies that are responsible for this problem, identify the solutions, and, working with the governor, get immediate action,” Allayaud said.

The Chronicle and USC Annenberg Center investigation revealed a recurrent, years-long pattern of problems and public health impacts involving indoor gun ranges:

- Hundreds of indoor gun range employees over the past two decades have contracted lead poisoning, and at least a half-dozen minors appear to have been poisoned, often through “take-home” exposure from range workers’ clothing, court documents and state health department records show.

- The health and safety agencies charged with regulating ranges routinely fail to follow through on violations and to communicate with each other, allowing unsafe conditions to persist.

- While no public agency tracks lead-poisoning cases among customers of gun ranges, thousands of Californians who have patronized dangerous facilities have been exposed to potential harm. On numerous occasions, Cal/OSHA and CDPH have measured airborne lead levels inside ranges that far exceeded federal safety standards, yet allowed those ranges to continue operating.

- Fines for health and safety violations are rarely assessed and are often drastically reduced.

- County environmental safety agencies, to which state agencies can choose to defer, often appear either unclear on their role or lacking the expertise to deal with the potential toxic threat gun ranges pose.

- In some cases, local officials have waived state-mandated environmental assessments of new ranges, exempting them from review by classifying them as recreational or entertainment facilities that pose no potential environmental issues.

- There are no statewide regulations aimed directly at these facilities.

These failures are highlighted in a number of cases uncovered in our reporting:

- At Jackson Arms, a South San Francisco gun range, three state agencies were aware of at least 85 lead poisoning cases among workers there between 2005 and 2018, yet the facility continued to operate. Its inadequate exhaust system spewed toxic lead dust outside the range, contaminating a creek leading to San Francisco Bay and spreading elsewhere into its neighborhood, which includes a children’s dance studio and airport hotels.

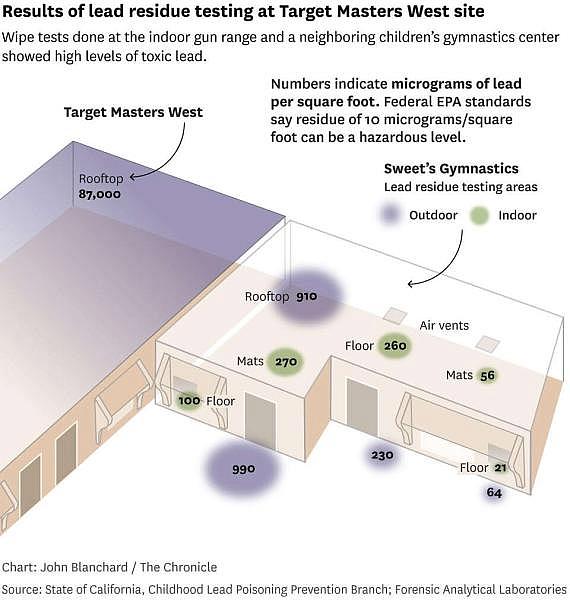

- State health officials were aware of dozens of lead-poisoning cases at the Target Masters West range in Milpitas, which operated for nearly 30 years before being shut down in 2019. A faulty ventilation system spread lead dust into nearby buildings, including a children’s gymnastics center, where lead was measured at 270 micrograms per square foot in some areas, high enough to cause permanent harm. The situation inside the range, said Dr. David Teter, an expert involved in the cleanup, “was the worst thing I’ve dealt with in 30 years of this kind of work.” The cleanup took nearly three years.

- In Riverside County, the Riverside Magnum Range admitted to disposing of lead waste in dumpsters and emitting lead into its working-class neighborhood. It was fined $1,000 and agreed to make repairs, and in 2013 the DTSC declared the problem fixed. Four years later, however, the state health department received numerous reports of lead-poisoned workers there. The range was fined again, but nearly five years later, the DTSC has yet to return to ensure that lead is not being emitted from the building.

- The Mangan Rifle and Pistol Range, run by the city of Sacramento in a public park, operated for more than a decade after the state health department identified hazardous conditions inside and high levels of airborne lead outside. The range, which the city finally shut down in 2015, contaminated the popular neighborhood park, forcing a $1 million cleanup. In 2021, Sacramento settled a lawsuit with former instructors and the wife of an instructor, who said she had suffered a miscarriage, for more than $1.2 million.

None of the lead regulatory agencies agreed to an interview with The Chronicle, though some provided written statements. None of those responses specifically addressed oversight improvements.

Gov. Gavin Newsom was unavailable to comment, said spokesperson Daniel Lopez, who referred the inquiry to the DTSC, an agency that allowed the Exide Technologies battery recycling plant in Southern California to operate for decades, even as it contaminated thousands of nearby homes with lead. The homes are undergoing a $600 million taxpayer-funded cleanup.

A DTSC spokesperson did not address The Chronicle’s findings, but suggested that the agency recognized the concerns, saying: “The administration has made a bold commitment to comprehensive reform of DTSC, including the creation of a new governance structure and providing fiscal stability for the department.”

Cal/OSHA regulators have the most contact with problematic ranges, but the agency’s record on enforcement is inconsistent, documents show. It often imposes minimal fines to offending ranges and fails to pass along crucial information to other agencies. Current and former officials at Cal/OSHA contacted for this story acknowledged that the agency has been hamstrung by a shortage of inspectors and morale problems. A spokesperson told The Chronicle the agency was working to improve communication with other regulators and to hire more inspectors, but offered no specifics.

Amid these regulatory failures, gun ranges may be growing in popularity. In 2020 and 2021, the FBI performed 2.9 million background checks for new gun purchases in California, a 50% increase over the previous two years. These purchases almost certainly expanded the number of gun owners in the state, estimated at more than 4 million prior to the pandemic, and the number that practice shooting at ranges.

Nationally, indoor gun ranges were a nearly $4 billion business, according to a December 2020 report by the business analysis firm IBISworld.

Yet documents show that California taxpayers are essentially subsidizing the industry, paying for millions of dollars in cleanups and underwriting an unknown amount of public health costs because most cases of elevated blood lead levels go undetected.

“There is no question we have a problem,” said a state official involved in the cleanups, whom The Chronicle agreed not to identify because they were not authorized to speak to the media. “There is no universal standard for gun ranges in California, and lead contamination sites just keep popping up.”

The debilitating and even deadly effects of lead have been known for centuries, and there have been efforts to mitigate its health impacts for almost as long.

In the past several decades, the U.S. and other nations have imposed ever-stricter lead abatement measures. The removal of lead from gasoline, which began in phases in 1976 and was completed by 1990, is considered among the public health triumphs of the 20th century. Between 1976 and 1994, the mean blood lead concentration in children dropped from 13.7 to 3.2 micrograms per deciliter, or mcg/dL. (A level of 5 mcg/dL indicates an unsafe level for children.) Some research suggests that the phaseout of lead from gasoline in the U.S. was responsible for a major decline in violent crime.

But despite these gains, lead continues to be a public health threat.

In California, despite its repeated air-quality and lead-contamination violations, the DTSC allowed the Exide battery recycling plant in Vernon (Los Angeles County) to operate with a temporary permit for 30 years. The DTSC also failed to require financial guarantees to clean up the contamination. The plant was closed by its operator in 2014 as part of a deal to avoid federal prosecution. Following the closure, DTSC discovered that Exide had contaminated more than 10,000 area homes with unsafe levels of lead. Cleanup costs will exceed $650 million, a 2020 state auditor report estimated.

Against this background, experts say, the lack of effective regulation of California gun ranges is perplexing at best.

Every time a gun with a lead bullet is fired, lead fragments and dust become airborne, posing a potential risk to anyone inside a gun range. A busy gun range can produce tons of lead waste in a year. If managed with a state-of-the-art ventilation system and cleaned properly, a range can operate safely.

Ventilation systems that remove lead dust through HEPA filtration systems and prevent the contaminant from escaping the building can cost about $25,000 per shooting lane. Multiple experts and organizations cite the importance of such systems, including the National Air Filtration Association. Yet California does not require them.

The Chronicle found numerous instances in which gun range owners were able to delay or reject pleas from regulators to improve their ventilation systems, allowing them to operate after faulty systems were discovered. In some cases, regulators have imposed fines on offending range operators. But documents show that fines are relatively rare and often minimal.

In 2013, the DTSC reduced an initial $119,900 fine assessed to the Riverside Magnum Range in Riverside County to $1,000, despite owners admitting to violations, including tossing lead waste into dumpsters and spreading lead into a nearby residential neighborhood. A DTSC spokesperson said the owner “received a credit” for repairing the range’s inadequate ventilation system. He added that the agency no longer reduces fines when an owner makes upgrades.

Yet problems at the Riverside range persisted. In 2017, the state health department received numerous reports of lead-poisoned workers there. In this instance, CDPH communicated with Cal/OSHA, alerting the agency in a letter: “We are referring Riverside Magnum Range to you for enforcement action due to ongoing and serious deficiencies in the employer's lead safety and respiratory protection programs.” Cal/OSHA fined the range $25,950, but then cut the fine to $5,500.

Five years later, the DTSC has yet to return to the range to ensure that the building is not emitting lead.

In some cases, the consequences of California’s dysfunction in regulating gun ranges have been severe. Lead dust conclusively traced to gun ranges has contaminated homes, playgrounds and waterways, including, in one case, a stream that leads to San Francisco Bay.

The range in that incident, Jackson Arms, operated at two South San Francisco locations over 30 years. At the range’s second location in a former flooring warehouse near San Francisco International Airport, chronic lead hazards lasted until owner Jason Remolona sold the building in 2018.

A review of hundreds of documents, along with interviews with former gun range employees and customers, found that CDPH and Cal/OSHA knew workers were continually becoming lead-poisoned and that the lead problem was worsened by an inadequate and dilapidated ventilation system. Meanwhile, local health officials responsible for monitoring hazardous waste in San Mateo County failed to inspect the range even once.

Cal/OSHA, which collected the most damning information about the range, declined The Chronicle’s interview request and did not answer questions about specific failures there. The worker protection agency said in an email that it was “committed to improving coordination on workplace lead exposures with local and state agencies” and that it had recently hired more industrial hygienists, who perform inspections.

The Chronicle left multiple voicemails and sent emails and text messages to Remolona, but received no response. An environmental consulting firm he hired to communicate with regulatory officials in San Mateo County also did not respond to requests to speak with him.

The problems at Jackson Arms began soon after South San Francisco’s planning department decided in 2005 that the conversion of the warehouse building to a firing range was exempt from environmental health review. Under state law, such exemptions are supposed to be allowed only if the project does not involve the “use of significant amounts of hazardous substances.”

But problems at Jackson Arms appeared quickly. That same year, CDPH traced a case of childhood lead poisoning to clothing worn home by a range worker. The child's blood level was at least 20 mcg/dL, high enough to cause permanent brain damage and developmental delay. Following an investigation, CDPH told Remolona he must provide adequate protective work clothes and that “work clothes and shoes must remain at the range.”

Remolona responded in a fax: “I have spoken to each employee about having an extra change of clothes at work and the response was lukewarm at best.” Records reviewed by The Chronicle show that CDPH did not insist that Remolona immediately follow state regulations when it came to protecting workers.

Cal/OSHA began monitoring Jackson Arms in 2007, after receiving a referral from CDPH “due to serious concerns about adequacy of employer’s lead safety program.” The agency identified 25 hazardous conditions that needed to be corrected.

Yet on multiple occasions over the following years, air quality readings taken by Cal/OSHA inside the range showed perilous levels of lead. On one visit, the worker protection agency found that airborne lead exceeded state and federal limits for exposure for an eight-hour day in just 10 minutes.

Remolona was able to repeatedly delay taking action to address the safety issues, documents show. On multiple occasions, he told state officials he could not afford repairs on his ventilation system, once saying he was on the verge of bankruptcy. The range was allowed to continue operating without the repairs.

In 2009, South San Francisco approved a major expansion of the gun range, including new classroom space. The city once again waived environmental review and imposed no ventilation requirements. In 2012, CDPH officials noted a buildup of lead in the added space, describing the area as having “no ventilation” and being “very dirty,” creating the potential for the ingestion of lead because of poor lead dust control.

In 2013, Remolona was given his “last chance” to make the range safe, documents show, after an in-depth inspection by Cal/OSHA showed that Jackson Arms appeared to be in worse shape than it was six years before.

“There is so much lead dust in there, that the photos are sparkly because the camera is focusing on the lead particles in air,” Cal/OSHA inspector Chris Kirkham told CDPH officials in an email obtained by The Chronicle. In a letter to Remolona following the inspection, Kirkham warned him that the violations could be categorized as “willful.”

Inspection findings “classified as ‘willful’ would involve penalties so high that they would likely threaten your ability to remain in business,” the letter read.

Documents show that the 2013 penalties imposed by Cal/OSHA were discussed internally as a final warning. In an email to colleagues, Julie Pettijohn, an official with CDPH who was in frequent touch with Cal/OSHA’s Kirkham, said he’d told her that “after his work with JA (Jackson Arms), if he receives another complaint, he will go in and give willful violations. In essence, he said this was their (JA's) last chance.”

But ultimately, the agency levied just $11,010 in fines, approximately a week’s worth of revenue for the busy range, according to former range employees. The facility continued operating without the necessary repairs. Over the next five years, CDPH data obtained by The Chronicle shows, 32 workers were lead-poisoned.

Garrett Brown, a former top-ranking Cal/OSHA official who left the agency in April 2021, said the minimal penalties for Jackson Arms were not appropriate. “If violations are willful, OSHA’s most serious category and usually for repeat offenders, that’s not something you can dial back,” he said.

“How did a decent inspection, resulting in seven citations requiring correction of unhealthy and illegal conditions, go nowhere? Why did workers continue to pay the price?” Brown asked.

In 2016, three CDPH officials visited the range. Remolona, documents show, again insisted that he could not afford to fix the ventilation system. A report of the visit says he also told them the interior of the range was usually cleaned up nightly by employees, but that “because so many of them are on medical removal protection he is doing the cleaning himself every other night.”

Medical removal protection is a federal standard set in the 1970s mandating that workers with a blood lead level exceeding 50 mcg/dL must be removed from exposure. That standard occurs fewer than a dozen times per year on average among California’s 17 million workers.

Former workers and patrons told The Chronicle that neither Remolona nor state regulators told them how bad the situation was at Jackson Arms.

Liza Normandy, who worked as a cashier, left the range in 2013, partly out of concern about elevated lead levels in her blood. Her doctor told her lead was present at 20 times what was normal for a typical adult and was the likely cause of her dangerously high blood pressure. She embarked on a career change, entering local politics, eventually becoming a City Council member and mayor in South San Francisco from 2013-18.

After reviewing records provided by The Chronicle, Normandy said she was “upset and baffled” by how two agencies charged with protecting workers and the public could have allowed the range to stay open.

“If Cal/OSHA had communicated the history and the extent of the problem, I could have done something about this as mayor,” she said.

State officials, though, were not alone in allowing the dangerous situation at Jackson Arms to persist. San Mateo County officials also took no action.

Under a state system called Certified Unified Program Agencies, or CUPA, San Mateo County’s Environmental Health Services department should have played a key role in ensuring the gun range was safe. Under CUPA, the state Environmental Protection Agency delegates regulatory oversight of many hazardous wastes and materials to counties. San Mateo County’s website appears to acknowledge this, stating that permits are required of all hazardous-waste producers to ensure that “all hazardous wastes are properly handled, recycled, treated, stored and disposed of.” But documents show that the agency never inspected Jackson Arms.

One official, county hazardous waste coordinator Dan Rompf, once came close. In an April 2018 email to Remolona, Rompf said he’d spent time shooting at the range, and that he planned to stop by to “have a discussion about hazardous waste procedures and whether a permit is required for your facility.” But Rompf never filed an inspection report or required the company to file a hazardous waste plan.

At the time, The Chronicle found, Rompf, who earns over $170,000 in salary and benefits, was running a consulting business called Lifecycle EHS, which offered “complete site inspections and regulatory consultations” for businesses that deal with toxic substances, according to its website, which was taken down after The Chronicle raised questions about it.

An ethics expert and current and former state environmental regulators said they were troubled that the county would allow a regulator to take outside work they saw as a clear conflict of interest.

Ann Skeet, senior director at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University, called it “terrible judgment.” Hal Thomas, a former chief criminal investigator with the DTSC, said the potential conflict of interest was “symptomatic” of the state’s overreliance on county regulators to rein in bad actors when “counties often lack the budget, expertise and will to get the job done.”

Documents provided by San Mateo County showed that Rompf did obtain permission to start a consulting business and that he promised not to take any work within San Mateo County, but did not require additional reporting by Rompf to verify that he’d abided by the commitment.

Preston Merchant, a spokesperson for San Mateo County, said the county had failed to take stronger action against Jackson Arms because it had been awaiting guidance from the state, particularly from the DTSC, about standards for gun ranges.

“Historically, gun ranges have not been regulated for hazardous materials or hazardous waste generation statewide,” Merchant said in an email.

A spokesperson for DTSC, however, said the agency had not told San Mateo County to hold off on regulating gun ranges or that specific guidance from it was forthcoming.

Thomas told The Chronicle that Merchant’s statement did not make sense to him. “The state’s hazardous waste laws are clear,” he said. “It doesn't matter if it’s a gas station or a gun range. It’s a crime to knowingly — or if you reasonably should have known — dispose of hazardous waste.”

Thomas said the regulatory system is “broken,” and the state’s policy of delegating environmental pollution cases to counties under the CUPA system needs to be revisited. “It’s always the same answer: This is the county’s territory,” Thomas said. “It’s a total cop-out.”

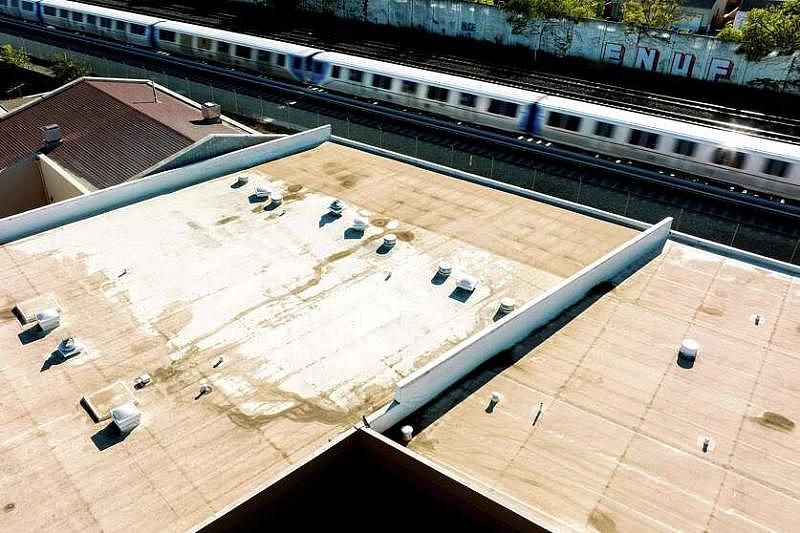

San Mateo County inspected Jackson Arms only after it closed in 2018, five years after Cal/OSHA’s last inspection. Reports describe the ventilation system as in deplorable condition, its ducts riddled with bullet holes.

Photographs from the inspection show a corroded exhaust fan on the roof caked with lead, and the roof itself covered with gray dust, which tests confirmed was lead in extremely high concentration.

Colma Creek, which drains into San Francisco Bay, runs adjacent to the now-shuttered Jackson Arms gun range in South San Francisco. Lead from the range’s ventilation system contaminated the creek.Noah Berger / Special To The Chronicle

Documents show that county regulators also discovered that lead from the range’s ventilation system had contaminated nearby Colma Creek. Although owner Remolona has admitted responsibility for the lead emissions, and San Mateo environmental health regulators have deemed remediation necessary, no cleanup of the creek or the surrounding area has begun since the range closed.

California statutes allow for both criminal and civil penalties when someone knowingly pollutes the environment with hazardous waste. While criminal prosecutions are rare, they do happen. In 2016, the owner of a Los Angeles-based scrap metal business was prosecuted for multiple felonies following a DTSC investigation. But despite years of failing to fix a ventilation system he was told on numerous occasions was inadequate, Remolona has faced no fines or criminal charges.

California’s 35 local air quality districts also should play a crucial role in flagging faulty ventilation systems. According to the California Air Resources Board, each district “maintains its own individual permitting program to reduce emissions from stationary and area-wide sources.”

But The Chronicle found that some air districts routinely fail to inspect ranges or require them to be licensed, even when it is clear that a gun range may be emitting toxic lead.

Airborne lead can be the most dangerous mode of lead contamination, public health experts say, because minuscule particles can easily lodge in the lungs, where they can wreak havoc on other organs, like the brain. Yet despite examples like Jackson Arms, a representative of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District said it had no plans to inspect existing ranges or require them to be permitted.

“Our preliminary estimates show that for an indoor gun range equipped with an air filtration system, an Air District permit may be required if more than 44,000 rounds of small-caliber ammunition are fired per day,” an agency spokesperson said in an email. “We believe the average number of rounds fired at a gun range is about 3,000 rounds per day.”

Peter Green, a UC Davis researcher who specializes in analyzing the spread of lead in urban environments, disputed the district’s logic in basing the safety level on the number of rounds fired.

“That calculation doesn’t make any practical sense,” said Green, a leading expert on airborne toxins. “They’re ignoring the real-world track record. It seems like the air district is assuming that filtration systems at gun ranges are perfectly calibrated – 99.9 percent effective. But all it takes is one loose screw on a piece of ducting and a whole lot of unfiltered air is being released.”

By contrast, the South Coast Air Quality Management District, which covers a large swath of Southern California, told The Chronicle that ranges are “subject to permitting requirements due to the emissions of lead.”

Still SCAQMD, which allowed the Exide plant to contaminate a large swath of Los Angeles even though its air-monitoring program detected high levels of airborne lead emanating from the plant, has been opaque in responding to The Chronicle about a troubled facility in its district, the On Target indoor gun range in Laguna Niguel (Orange County).

An inspection by the DTSC found lead contamination on the building’s roof of over 250,000 micrograms per square foot, a level that made it nearly one-quarter lead. Tests of soil next to the gun range also showed clear lead contamination. The range was fined, and a DTSC spokesman told The Chronicle in early 2021 that the range had since worked with the local air district to repair its ventilation problems.

But the South Coast air district inspected the range only after it received questions from The Chronicle in late 2021, and has provided no specifics of its findings, saying that its investigation is “ongoing.”

Requiring air districts to permit and subject gun ranges to periodic inspections should be a “no-brainer,” Green of UC Davis said. “We make sure cars have pollution controls, and we inspect them every couple of years to make sure they are operating properly. Of course gun ranges should have, at a bare minimum, standards and regular inspections.”

As happened with Jackson Arms, new ranges often open in California without environmental or safety reviews, The Chronicle found.

In more than a half-dozen instances, local officials waived environmental review for new indoor ranges, sometimes by classifying them as recreational or entertainment facilities, or otherwise declaring them exempt from scrutiny required under the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA. Such waivers are problematic because the type of advanced HEPA filtration system recommended by experts can both protect the external environment and help eliminate airborne lead inside the range.

“It’s not exactly news that lead kills, or that it’s found in the soil near gun ranges,” Kathryn Phillips, former director of the California Sierra Club, said. “This kind of threat is exactly why we have CEQA protections, to keep contaminants like lead from harming people and the environment. To pretend that a gun range is somehow hermetically sealed is irresponsible.”

In 2017, the Planning Commission in the Sierra foothills city of Placerville (El Dorado County) waived a CEQA review for the Hangtown Range, labeling it an “entertainment” and “recreational” facility. Three years after it opened, Cal/OSHA, following up on reports of lead-poisoned workers there, found hazardous levels of airborne lead inside the range and fined the facility $13,990, later reduced to $4,400.

Records obtained by The Chronicle show that Cal/OSHA reduced another fine of the range for exposing workers to unsafe levels of airborne lead from $6,300 to $2,400. The agency then marked the violation as “abated.” But in reality, as at Jackson Arms, Cal/OSHA failed to perform any follow-up tests or examine the ventilation system to make sure it was working properly. Instead it gave credit to owner Richard Rood for making “good faith efforts.”

The gun range is located just 15 feet from Hangtown Creek, which empties into the American River, a drinking water source. Google satellite images taken in 2021 show black streaking near ventilation fans on the range’s roof. Jeff Van Slooten, a lead contamination cleanup expert, told The Chronicle the images appear consistent with lead streaking he has seen elsewhere.

“The only way to know would be to test,” Van Slooten said.

But Blair Robertson, a spokesperson for the California Water Board, which is tasked with making sure waterways are free from health and environmental threats, told The Chronicle that “there are no plans to conduct testing near the Hangtown Range in the immediate future.”

Robertson said the water board is focused on threats from outdoor ranges, because “when shooting ranges are situated indoors, spent ammunition is not exposed to precipitation or surface runoff and therefore doesn’t pose the same threat to water quality as it would if it were outdoors.”

In another instance, the planning board in Dublin waived environmental review for a large new range called Guns, Fishing and Other Stuff that opened in 2015. Just weeks after the range opened, records show, workers noticed that the ventilation system was spreading what turned out to be lead-tainted smoke. One worker alerted Cal/OSHA.

Cal/OSHA inspected the range and issued a fine of $20,600. But records and interviews with former employees show that the agency allowed employees to continue to work in the hazardous conditions.

Ashley Baxter, a college student and avid shooter who worked at the range’s gun store, said she started experiencing headaches while other workers had symptoms like nose bleeds. “We would say to each other, ‘Wow, the range is busy today; you can really smell it.’ I had no idea we were getting lead-poisoned.”

Cal/OSHA had Baxter and other workers wear monitors at work to measure airborne lead. The monitors, an inspection report shows, determined that workers were exposed to lead levels far exceeding state and federal limits.

Cal/OSHA regulations state that workers must be informed of such results. But Baxter continued to work in the store for months before the ventilation system was fixed, Cal/OSHA records show, and Baxter says she was never told of the danger. “What if I had been pregnant?” she said.

Brandon Brinkman, a former Marine who worked as a range manager at Guns, Fishing and Other Stuff, says he became so badly lead-poisoned he had to stop working until his blood lead levels decreased a month after testing.

“I have a pretty high tolerance for risk,” Brinkman said. “I thought any gun range in the Bay Area would be overregulated if anything.” Frustrated, Brinkman says he left the range in 2016 and has since moved to Texas, working in the security industry. He still frequents gun ranges. “Ironically,” he said, “they feel a lot safer here when it comes to lead safety protocols than I experienced in California.”

A storefront at 122 Minnis Circle in Milpitas is the former home of the Target Masters West gun range. The range’s faulty ventilation system spread lead dust into nearby buildings, including a children’s gymnastics center.Noah Berger / Special To The Chronicle

None of the public health and safety agencies presented with the findings of The Chronicle/USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s reporting suggested any specific reforms to indoor gun range oversight.

Legislative action, experts said, is one route to better regulation.

In 2019, after the discovery of what one expert described as a lead nightmare at the Target Masters West range in Milpitas, Newsom signed legislation mandating that Cal/OSHA conduct inspections of any businesses where employees are known to have been lead-poisoned.

The legislation, authored by Assemblymember Ash Kalra, D-San Jose, increased lead-related inspections by Cal/OSHA from none in 2019 to 27 in 2020. The majority of inspections occurred in battery recycling operations and gun ranges. Last year, 41 businesses were referred to Cal/OSHA, stemming from 159 poisoning cases, according to CDPH. Nine of the employers were gun ranges.

In 2020, Assemblymember Kevin Mullin, D-South San Francisco, whose district includes the site of the former Jackson Arms range, introduced legislation that would require indoor gun ranges to use only lead-free bullets. Such bullets are about 50% more expensive than conventional bullets, but the price would likely drop if California and other states created more of a market for them.

But after the National Rifle Association and other gun rights organizations targeted Mullin’s bill, he withdrew it. A staffer for Mullin, Meegen Murray, told The Chronicle that “with COVID going on, this just wasn’t the right time for this fight."

Gabriel Fillipelli, an Earth sciences professor at the University of Indiana who studies the impacts of lead contamination at gun ranges, said changes must be made, calling the issues that The Chronicle identified in California “deadly serious.”

“In the short run, there needs to be focus on improving ventilation systems,” he said, “but the real focus should be on creating a lead-free environment. Alternative ammunition like copper bullets perform just as well as lead bullets at gun ranges.”

California could also adopt universal standards for lead safety at ranges. At present, there are no statewide standards even for basic safety measures like adequate ventilation systems or showers for workers so they don't track lead home.

“That is long overdue,” longtime Cal/OSHA official Garrett Brown said. “Indoor gun ranges have been a big problem in California for a very long time.”

Allayaud of the Environmental Working Group, who worked with Kalra to pass the 2019 legislation, expressed frustration at the continuing problems at gun ranges.

“If Cal/OSHA learns about a ventilation system that is poisoning workers, they need to tell the DTSC to make sure lead isn’t also being illicitly released into the environment. Air districts need to be instructed that this is a real problem and to stop being in denial,” he said. “We need real enforcement, with fines, and for unsafe gun ranges to be brought into compliance or shut down before more people are harmed.”

[This article was originally published by San Francisco Chronicle.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.