Living Lonely Part 3: When the Ill Are Invisible

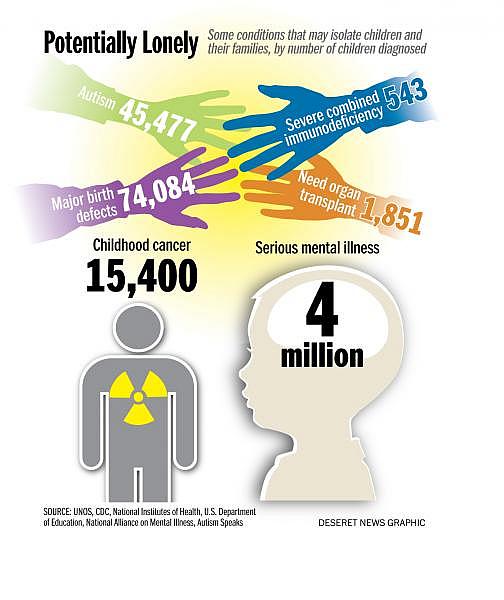

Childhood cancers, behavior-impacting disabilities like autism, extremely brittle bones or compromised immune systems are just some of the conditions that may leave kids — and by extension, their families — feeling lonely.

Lois M. Collins wrote the "Living Lonely" series for the Deseret News as a 2013 National Health Journalism Fellow. In the series, she examines the health effects of loneliness. Other stories in the series include:

Lee Gregory walks with son Zach to his mother Tiffany Gregory's car in Salt Lake City Dec 7, 2013. Zach's medical and developmental disabilities make him fragile and his family sometimes feels intensely lonely, even in a crowd. (Jeffrey D. Allred/Deseret News)

Zach Gregory is as pale as the milk he’s just knocked over with his elbow. His dad is trying to wipe the spill off the scarred wooden dining table with one hand, while using his other to stop his son from gouging himself in the face. There’s a semi-perpetual big pinkish-red circle dead center in the 18-year-old’s forehead, where he smacks himself whenever he gets the chance.

Lee Gregory has finished feeding his son and in a few minutes, he will put Zach’s plastic helmet and the arm guards back on, then guide his son downstairs and change his diaper. It’s almost bedtime and though it will take Zach a few minutes to wind down, he’ll soon drift off, the house enveloped in brief calm before the next day starts very early with wrestling Zach into clean clothes so he can be picked up for school.

Lee Gregory feeds breakfast to his son Zach at their home in Salt Lake City Dec 7, 2013. Zach goes to school most days and the family sometimes has respite assistance, but caring for the boy challenges the whole family. (Jeffrey D. Allred/Deseret News)

Zach is profoundly deaf, has poor vision and is cognitively delayed. Experts estimate his behavior is similar to that of a 1- or 2-year-old baby, which means he’s restless and rough without intent to harm anyone. He’s never spoken, but he understands a couple of words in sign language. His family tried to teach him more signs, but it didn’t take.

When Zach was little and so much more portable, his folks would take him to church or to watch the fireworks. He’s obsessed with balloons — simply adores them — and people were fairly tolerant when a little Zach crawled from his blanket to theirs to swipe one. These days, Gregory said he never knows how people will react.

Still, it’s less an issue now because Zach’s behavioral challenges mean his family doesn’t take him out in public much. Even if they did, lots of people are uncomfortable with his disabilities and unsure how to act, so they simply pretend they don’t see him — or his parents or brother or sister, if they are with him.

A walking buddy once asked Lee Gregory how it felt to be treated like he's invisible when he's with his son. “I try not to pay attention to that,” Gregory replied.

Childhood cancers, behavior-impacting disabilities like autism, extremely brittle bones or compromised immune systems are just some of the conditions that may leave kids — and by extension, their families — feeling lonely. Today, the Deseret News concludes a three-part series on the effects of loneliness on vulnerable families, this time focusing on children with illness or disability.

Encounters with other people are “each a little spark of joy in the day,” said Dr. Norman Rosenthal, psychiatrist and clinical professor at Georgetown University School of Medicine. “Add the sparks together, you have a joyful day. If you have none of those sparks, life becomes lusterless.

“I think that’s the problem with isolation,” said Rosenthal. “Some people like their own company, and that’s fine. But primates need a social group and connection with others.”

So Many Challenges

Bonnie Midget can easily list children’s medical conditions that isolate families or some of their members. As spokeswoman for Primary Children’s Hospital, she’s seen parents struggle to find help or a moment’s respite when they have a child with multiple serious problems who cannot be left alone. If a medical condition is complicated enough, even relatives and close friends are afraid to step in. “The parent never gets a break from the day-to-day care,” she said.

She’s seen children who, like Zach, have impairments that make it hard to take them anywhere, or who are so frail they require constant attention. “Even if they attend a social gathering, they are unable to participate in activities because they must attend to their child,” said Midget.

Cancer or an immune disease also spill over in unexpected ways.

Lisa and Burt Larsen of Brigham City had seven boys, infant to 10, when Tommy was diagnosed with AML leukemia. They had a huge support network of family and friends, but the hospital was a lonely place, despite efforts to make it cheery. His parents took turns being with him or home with the others. “We were separated from half the family, never quite a full family, always apart. There were family functions he couldn’t go to. There were things we were sort of left out of. We didn’t want to make the other children miss opportunities, so on movie night, one of us would stay with Thomas.

“I definitely think he was lonely,” Lisa Larsen said of her son. “He was sometimes sad and wanted company.” Neighborhood friends and siblings helped by Skyping with him. So did folks from church. But his tears weren’t just because he didn’t feel good much of the time.

Demands on the family of seriously sick children or those with certain disabilities can weigh heavily on families, said Karla Jennison, a clinical social worker at Primary Children's Hospital.

If both parents have been working, one may have to quit, which impacts both finances and a person’s sense of self. It’s very hard to find caregivers or day care to take care of a child who’s medically fragile or has special medical needs. Parents do it — and learn to run complicated equipment like feeding tubes and ventilators, as well, to provide the round-the-clock care some children need, Jennison said.

Parents who are lonely face all the well-documented health ramifications, like anxiety, depression and higher risk of heart disease. “A parent who is running on empty, physically or emotionally drained, cannot be present for the child,” Jennison said.

They also must be mindful of whether the child is suffering the effects of loneliness.

Autism is yet another condition that isolates people and leads to loneliness, Rosenthal said. It hampers communication and interaction. “Those children are going to be naturally quite isolated and often the mother tends to be the main channel of communication with the outside world. I think they try and adjust, but may find autistic children are resistant to seeking out others. They may not have the scope of opportunities that most people have,” said Rosenthal.

The moment Ja Lynn Prince’s son Jordan, 23, left school, he started losing ground, said the Potomac, Md., mother. In 18 months with no services, the young man, who has autism, started pounding holes in walls and expressing frustration in other ways. She blames loneliness. “The isolation is real,” she said.

Finding Support

Joe and Eileen Christensen live blocks from the Gregory family, though they knew nothing about them or how similar are the challenges the two families face. Scot Christensen was born 25 years ago with a genetic syndrome that includes hydrocephalus, mental retardation, scoliosis, seizure disorder, inability to communicate and complete dependence on others. There are also some differences, like the fact that Gregory fed his son a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich and banana last night, while Scot eats through a tube. Just like Zach, he’s too big to carry around.

(Jeffrey D. Allred/Deseret News)

“We have felt like we’re flying blind most of his life,” said Eileen Christensen. “In spite of that, we have put a lot of effort into giving Scot a full life. When he is healthy, he has a number of activities to keep him engaged, entertained and socialized. When he is sick and/or hospitalized, the isolation is hell — very depressing.”

Eileen is shocked by how crushing his care can be then. “I see how quickly I get depressed and the world just caves in on me. I need to be socially connected.” Early on, she realized she’d have to make a decision: “Am I going to be positive? Am I going to let it crush me? It’s a daily decision and it never gets easy. But I always decide I’m going to power through.”

Powering through means she takes him everywhere with her, in part to avoid loneliness herself, she said. When he’s too sick, it’s awful for both of them. “We made a decision and you have to be in a good place to make that decision. I completely get people who give up and can’t do it. I’ve felt that way plenty of times, too.”

Scot gets strange looks when he drools or makes funny noises. Also like Gregory, Christensen is profoundly grateful when someone just speaks directly to her son or asks her a question about him.

“I don’t know a way to bridge the discomfort people feel. It’s okay to talk. I would love people to ask questions, love to be approached.” She feels less isolated, though, because she has found a support group, the Utah Kids Parents Group, she said.

Go away!

In a crisis that had layers of tragedy built in, one of the worst parts of the AIDS epidemic was the terror it brought. Early on, those with the disease were forced into what sociologist Pepper Schwartz calls “hysterical isolation.” Children with AIDS were among those who suffered the most. “You don’t realize how big it is until you experience it. It sort of takes you out of being human.”

The mind-body connection is extraordinarily powerful, said Schwartz, a senior adviser to the Council on Contemporary Families. When children are untouched or unmoved, when no one watches for small changes, a cascade of challenges starts that is hard to stop. Depression and loneliness may be the least of it but bring other things: Illness, lack of interest, poor appetite, brain fog, exhaustion and more. The immune system goes awry, as do hormones.

The health challenges can reach beyond the child to siblings who become lonely because they can’t bring friends home or participate in activities for fear of exposing the sick child to something bad. It can reach parents whose challenges range from being worn out to having high levels of stress and isolation.

Jill Heaps will never forget the nearly three years her family spent in semi-isolation after Emily, now 12 and the youngest of three children, was diagnosed with Severe Combined Immunodeficiency. Media call it “bubble boy” disease.

“She was in complete isolation and we went nowhere but to the hospital and my parents’ house for 2½ years,” said Heaps, of Sandy, Utah. The first bone marrow transplant, when Emily was 6, didn’t solve it. After another transplant, life is nearly normal by almost any family’s definition. Emily still has some residual effects, including hearing loss, and things crop up, but “she’s actually doing really well.”

While she was so sick, siblings Jacqueline (later her donor) and Thomas were frequently farmed out to other people. “We called Emily our community baby, because we could not have done it on our own,” said Heaps. Backup families were part of an emergency plan. Thomas refers to a time mom wasn’t around for two years.

They didn’t eat out or go to movies. They steam-cleaned the house daily. Finally, knowing the other kids were becoming too left out, Jill and Matt Heaps created a play zone in the basement. A friend or two in families that were entirely healthy could sneak in through the back entrance, go downstairs and play. “Emily didn’t know we had a basement,” she jokes. She sprayed everyone with Lysol, but it was doable.

“It was a very high-stress, lonely time,” said Heaps. “Isolating. I did go running with my friends in the morning. That was my therapy and I saw a counselor about anxiety. We learned that we had to let people in.”

Emily hated to wear a mask when she was allowed out. Thomas was sad that people brought gifts for the girls — who were donor and recipient — but not him, right after the transplant. It was hard being left out, his mom said.

Jennison said offers to help should be specific. Asking what can I do may be met with a blank stare. It requires an already-stressed family to figure out a way for you to help. They’ll probably just say “nothing.” Offering to take the other child to soccer practice is better. If the family says no, don’t be offended.

She pointed out that adolescents want nothing more than to fit into a peer group. That illness makes a family different is hard for them.

“The thing that strikes me about these families is the strength and resilience they have,” she said. “They do their best and incorporate the illness into part of their life, but not into all of it. Most lead a new type of normal life, but still have fun and go out.”

She said families tell her they’d not wish for the condition, but few would skip the lessons they learned, which have been valuable.

Tiffany Gregory, Zach's mother, understands that. “You love your child for who he is. He also opened up other options and opportunities we would never have had,” she said. “We've made friends we would never have known.”

This story was originally published in the Deseret News.

Photos and video by Jeffrey D. Allred