Mobile home parks offer refuge from California’s housing squeeze. Who’s watching them?

The story was originally published in Cal Matters with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Data Fellowship.

An aerial view of Stockton Park Village, a 34-space mobile home park in unincorporated San Joaquin County on Jan. 27, 2023.

Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

Bobby Riley moved to Stockton Park Village to live out his days in peace.

In 2018, the 87-year-old retired construction worker tucked his used camper trailer into the farthest lot of the horseshoe-shaped mobile home court off a tree-lined street in the outskirts of Stockton. The community’s handyman, Buzz, helped him build a porch and a patio to ground his trailer and enclosed it with a white wooden fence. He set up a swingset on the grassy common area across the way for when his granddaughter, Brooke, came to visit.

But the little piece of heaven he sought soon became a living hell.

Park owners Howard and Anne Fairbanks appear to have abandoned the property in early 2020 and later that year manager Maria Mendoza died, opening it up to squatters and illegal dumping, according to interviews with the state housing department and court records from a nuisance lawsuit filed by the county of San Joaquin against the Fairbankses. The once-green common area soon filled with wood pallets, dirty mattresses, broken-down cars, discarded washing machines and heaps of gleaming black garbage bags teeming with rats, cockroaches and flies, photos and written reports from state and county inspectors show.

The worst for residents were the pools of putrid brown liquid they have had to wade through, on and off, for nearly four years. County officials first observed surfacing sewage across the park in early November, 2020, according to Zoey Merrill, deputy counsel for San Joaquin County. By February 2021, the problems had gotten worse. A month later, Roto-Rooter came out to fix the problem at the county’s behest but was only partially successful and said the only permanent solution would be to replace the sewer lines at an estimated cost of $100,000. Throughout 2021 and 2022, Roto-Rooter periodically affected minor, temporary solutions, but nobody has replaced the sewer lines yet.

That tracks with what Riley told CalMatters: He had to live with the stench, which seeped into his trailer’s thin walls, for “several months.” His neighbors say it still stinks when it rains.

“It was even terrible in here,” he said, sighing. “It was just shit everywhere.”

The Fairbankses did not respond to the lawsuit or six emails and several phone and text requests for comment from CalMatters. A person who answered the phone at North Gold RV Park in North Dakota, who gave her name as Tiffany, confirmed that Howard Fairbanks owned that park, too, and said she had passed along CalMatters’ request for comment.

It’s hard to believe that the park — now a barren dirt field dotted by a few remaining trailers that are home to about a dozen residents — and its issues are well known to the state of California. Inspectors at the California Department of Housing and Community Development, which oversees health and safety at California’s mobile home parks, started documenting Stockton Park Village’s deterioration in February 2019 when it went out to inspect one of dozens of health and safety complaints it received starting in 2018.

But when residents file a complaint against a mobile home park, each complaint is treated separately. It can become a game of Whac-A-Mole: Owners can fix one citation over a period of months while residents and the state have to start a separate process for each problem stemming from an overarching issue.

So while the state has wielded most of its enforcement powers at Stockton Park Village, its residents have endured varying degrees of filth and hazardous conditions for more than four years.

The state of California has given the housing agency limited powers to intervene when conditions at mobile home parks get this bad. It can strip owners of their ability to collect rent until they fix the problems — which records show it did three times at Stockton Park Village. But it can’t step in and help those residents itself. Instead, it can eventually refer the problem to the local city or county district attorney’s office, which can bring a civil action to abate the nuisance and ultimately appoint a receiver, or temporary caretaker — which it did in the summer of 2021.

Bobby Riley, 87, at his home at Stockton Park Village in the outskirts of Stockton on Jan. 27, 2023. Riley said he has been relying on a generator for electricity and bottled water for bathing since earlier that month.

Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

The state agency’s last lever — which it rarely pulls — is to shut down the park. That would make it illegal for residents like Riley to live there, and further diminish the last traces of affordable housing in California.

CalMatters reviewed hundreds of pages of records in a five-month investigation of California’s mobile home parks. Stockton Park Village is not representative of all or even most mobile home parks in the state. State housing department records show it’s one of about 40 parks with suspended licenses in a state with about 4,500 state-licensed mobile home parks. But county officials, the park’s receiver, attorneys for the park’s residents and advocates who work with residents elsewhere say they believe the number of mobile home parks in disrepair could actually be much higher because of their old age and shoddy construction.

Under state law, a park could go up to 20 years without a full inspection; inspectors rely mainly on residents to file complaints. While inspectors visited 91% of state mobile home parks in the last decade, according to a recent state audit, only half were full inspections, and 330 parks got no visit at all.

“Parks that are that bad probably represent 50 or 60 parks in the state,” said Jerry Rioux, a longtime housing policy consultant currently working with the state housing department on behalf of the California Coalition for Rural Housing, a Sacramento-based nonprofit. “But there’s the next level (of parks) that are not quite as bad. But if they don’t get inspected for 10 years, how bad will they be?”

The dilemma in Stockton illustrates how the state’s crushing housing affordability crisis has forced the state into a Catch-22: shut down problematic parks and displace residents who are often one step away from living in their cars, or use enforcement powers sparingly as health and safety emergencies fester.

The housing department sees in Stockton Park Village “a shining example of a system working according to plan,” said Kyle Krause, deputy director of codes and standards at the state housing department.

Garbage piles have taken over common spaces at Stockton Park Village on Nov. 22, 2022.

Photos by Rahul Lal, CalMatters.

Garbage piles have taken over common spaces at Stockton Park Village on Nov. 22, 2022

Photos by Rahul Lal, CalMatters.

Garbage piles have taken over common spaces at Stockton Park Village on Nov. 22, 2022

Photos by Rahul Lal, CalMatters.

His reasoning: The state inspected the park regularly in response to complaints, eventually triggering a parkwide inspection. The department provided the owners plenty of notice and chances before cutting off rental income, which they would need to fix issues and keep people safely housed. When those failed, it let the local government take over. After a drawn-out process, a new owner is to take over Stockton Park Village, preserving it as a housing option.

“I think things are working, and they're maybe frustrating for some and maybe painful for others, because it takes time for those violations to ultimately be corrected,” Krause said. “But there are proper tools in place for all those things to happen.”

The end of the line

Mobile home parks are the end of the line for many. As California’s pulverizing housing costs have squeezed half a million people out of the state and tens of thousands of people into its streets, these parks offer refuge for an estimated 1.6 million residents, who tend to be older and poorer than the average renter.

Heather Riley bought her father a used camper trailer in Chinese Camp, in the foothills of the Sierras, and moved it into Stockton Park Village for him four years ago. It was his chosen retirement community, after the friend who for years rented him his house, also in Stockton, fell ill and his brother sold the home. Riley’s name continues to languish on multiple waitlists for government-subsidized affordable housing, his daughter said.

His trailer is cramped but cozy. Nestled between his built-in bed and a loveseat, the self-proclaimed Okie Boy sits long hours in his pilled black Reebok hoodie and his leather armchair watching Westerns. Mementos from 87 years of life frame his TV screen, including photographs of his children and his old motorcycle club.

“I was president of that club for 21 years,” he wistfully recalled on a cold January morning.

Before the manager stopped collecting rents in 2020, Riley was paying less than $400 a month for his lot. Average rent for a 1-bedroom apartment in Stockton now costs more than three times as much. Across California, mobile home residents paid a little more than half the monthly housing costs of people living in single-family homes in 2021, according to the American Housing Survey, a subset of the U.S. Census.

But a mobile home offers none of the security of a single-family home. Residents like Riley own their homes, but rent the dirt they sit on, and have little to no control over the infrastructure they’re hooked to. Older mobile homes cost thousands of dollars to move, if their rickety frames can even withstand it, and most parks don’t accept older trailers like his.

Amid the desperation for affordable housing in the wake of World War II, factories spat out mobile homes, and parks sprang up across the country to accommodate them, reaching their peak in the 1970s. In California, nearly 90% of parks for which the state housing department has construction date data were built before 1980. Stockton Park Village was built in 1948, state records show. But parks weren’t built for permanence, and housing experts say that’s evident by their often sputtering water, septic and electric systems.

“Those systems are increasingly failing, partially because they weren't built to super high standards to begin with and partially because there's, in some cases, a tendency to skimp on maintenance and to maximize profits for landlords,” said Zach Lamb, a planning professor at University of California, Berkeley, who specializes in mobile home parks. “And so you have many, many communities that are facing pretty dire infrastructural challenges.”

Discarded mattresses and other trash encroach on a playground at Stockton Park Village in the outskirts of Stockton on Nov. 22, 2022. Bobby Riley, 87, said he bought the swing set for his granddaughter but will soon have to take it down because the garbage hasn’t been picked up for months.

Photo by Rahul Lal, CalMatters

A 2022 report from the housing department addressed to the state Finance Department notes “deferred maintenance of park infrastructure and aging manufactured or mobile homes have thrown into question the viability of these homes and made mobile home park residents particularly vulnerable to climate change and displacement.”

The report goes on to say that “many mobile home park owners are financially unable to rehabilitate their parks.”

It’s hard to quantify exactly how many parks have failing infrastructure because no one is keeping track. But studies from California and other states show parks everywhere are hurting.

Climate change disasters such as flooding, wildfires and extreme heat, for example, are more likely to impact mobile homes than any other housing type. Residents have dirtier drinking water, and less reliable access to it, than Californians living anywhere else, recent studies show. Of the at least 383 parks in California that run their own water systems, 70% of them are at risk of failure — a higher proportion than any other housing type, according to an unpublished analysis of water system risk shared by Gregory Pierce, co-director of the Luskin Center for Innovation at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“I can tell you, especially from talking to people who are supposed to be overseeing and trying to fix issues where people don't have clean water in the state, mobile home park-run water systems stand out,” Pierce said.

Empty mobile home lots at Stockton Park Village in Stockton on Jan. 27, 2023, after the San Joaquin County deputy counsel says the sheriff's office removed garbage and trespassers.

Photos by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

Empty mobile home lots at Stockton Park Village in Stockton on Jan. 27, 2023, after the San Joaquin County deputy counsel says the sheriff's office removed garbage and trespassers.

Photos by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

Audit finds oversight is lax

California’s Legislature first enacted the Mobilehome Parks Act in 1967 to regulate park conditions. The law dictates health and safety basics: Common areas need to be well-maintained and individual homes properly hooked up to the sewer, water and electrical lines. Sewage leaks and trash buildup, for example, are prohibited. Experts like Pierce say it barely scratches the surface of bigger environmental concerns, however, such as poor drinking water or wildfire risk.

The state housing department conducts parkwide inspections to ensure the law is followed in just about 3,700 parks in the state, while city and county governments that have requested the authority oversee another 800 parks.

A 2020 report by then-State Auditor Elaine Howle found that in the previous decade, the state inspected less than half, or 45%, of parks under its purview. State law includes only a goal — not a requirement — for the agency to conduct parkwide inspections at 5% of mobile home parks each year.

“Obviously the percentage, five percent, is not enough,” said former state Sen. Connie Leyva, a Democrat from Chino. “Twenty percent? I don't know what that looks like, how much staff that is, but we definitely need to up it from five percent. It’s ridiculous. Ridiculous. It’s laughable.”

Leyva requested the audit to give the Legislature plenty of time to refine the inspection program before it’s due for reauthorization, on Jan. 1, 2024.

State inspectors did, however, visit an additional 37% of parks in response to complaints and conduct permit inspections in 9% of additional parks between 2010 and 2019.

But those spot-checks are usually limited to review of a single item, like a new porch — which the agency has to permit — or a gas leak at a single mobile home. In parkwide inspections, the inspector looks to make sure the entire park is safe. An inspector might notice other problems during a complaint inspection, such as trees leaning on power lines — but they are not required to write up such violations, said Rick Power, who supervised the State Auditor’s report.

“You go down into the L.A. area, there are some (parks) down there that are like 1,500 spots,” Power said. “Those are large parks. And if you're showing up and you're going to one unit, there's a whole lot of stuff out there that you may not be seeing.”

Inspectors hadn’t stepped foot in 9%, or more than 330 parks, over the same time frame.

“We still found that there were parks over the last 10 years that had never been visited,” he added. “And that was kind of a red flag for us. Because if your job is to make sure that the health and safety of the residents are being kept up, and you're not there for 10 years, that's kind of a problem.”

Krause, from the housing department, said he believes the system, “as prescribed by law and regulation, is adequate to ensure the minimum health and safety is maintained in all the parks in the state.”

Bobby Riley has been relying on bottled water for drinking, washing dishes and bathing, since January.

Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

Bobby Riley has been relying on bottled water for drinking, washing dishes and bathing, since January.

Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

In choosing which parks to inspect, the state housing department told the auditor it prioritized parks “based on the number and severity of complaints the parks receive and the time since the last park inspection.” Parks without any recorded complaints, then, had “a risk of serious undetected health or safety violations,” the audit concluded.

And those parks are home to some of the state’s most vulnerable residents, advocates told CalMatters.

“I get calls almost every day from people who have varying stages of information about what their rights are,” said Hilary Mosher, a volunteer regional manager in Northern California for the Golden State Manufactured-Home Owners League, the main lobbying group for park residents. “When I suggest that they file a complaint with (the state housing department), about 90% of them back off because they're afraid of retaliation.”

Two years after Colorado relaunched its own complaint-based inspection program for its 730 mobile home parks, that state found more than 70% of residents didn’t know about the program. There’s no such survey data for California, but most advocates and lawmakers told CalMatters things are not much better here.

“They’re not familiar with (the complaint system) at all,” said Leyva, who led the state Senate Select Committee on Manufactured Home Communities for seven years.

Between July 2019 and October 2022, the state received at least one complaint from the public — which could be neighbors, residents or even park managers — at 1,730 parks, according to a CalMatters analysis of state data. It received no complaints about 1,953 parks.

“We still found that there were parks over the last 10 years that had never been visited.”

RICK POWER, SUPERVISOR OF THE STATE AUDITOR’S REPORT

Many parks in rural areas are home to not only low-income residents, but also undocumented immigrants, advocates explained. If they even know how to file a complaint, and can get over language barriers, residents are afraid their park owner will know who filed it.

“People would rather live in bad conditions than have nowhere to live,” said Ilene Jacobs, an attorney at California Rural Legal Assistance, a legal aid group that represents Riley and many of his neighbors, as well as other mobile home park residents across the state.

The housing department assured information about a complaint remains private until an investigation is closed. Complaints can also be filed anonymously, although that makes follow-up hard. And if the issue that generated the complaint is gone by the time an inspector shows up, there’s nothing for an inspector to cite, the housing department said.

Residents have another reason to worry: Complaints and parkwide inspections can result in code violations against not just park owners, but homeowners. If an inspector finds a code violation on a resident’s property, such as a missing staircase railing or a build-up of outside junk, they can get cited. If they don’t fix it in time, the violation goes to the park owner — who can then use it as grounds for an eviction.

“Inviting (the housing department) over there may have unintended consequences,” said Angélica Millán, an attorney at Legal Services of Northern California, another aid group.

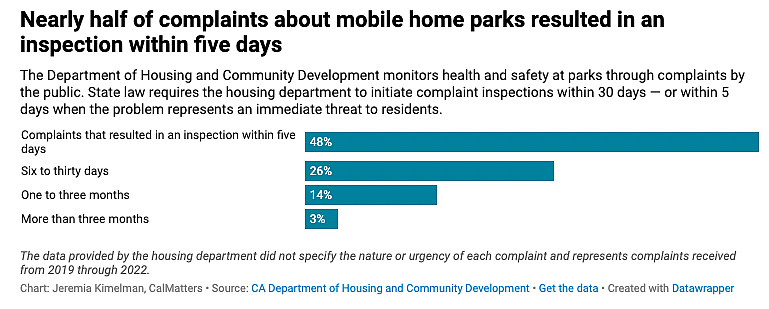

Of the roughly 5,700 complaints that CalMatters reviewed — all complaints filed about mobile home parks between July 2019 and October 2022 — just under half received a response within five days. Barely more than a quarter took three weeks or longer to get a response. About 250, or 3%, of complaints did not get a state response until three months or more had passed.

The data provided by the housing department did not specify the nature or urgency of each complaint and represents complaints received from 2019 through 2022.

“I think it really erodes any trust that anyone might have in the system when there's that much of a delay,” said Madeline Howard, an attorney at Western Center on Law & Poverty.

Among other recommendations, the auditor instructed the housing department to broaden its selection criteria to include parks it hadn’t visited at all in many years, including those that hadn’t lodged any complaints, and improve its response times. By last year, the housing department had adopted every recommendation made by the State Auditor, said Power, from the State Auditor’s office.

To fill in the gap for residents who don’t know about the complaint-driven system, Colorado is now hiring its first two inspectors to conduct proactive, parkwide inspections like California’s, and a community outreach liaison, said the director, Christina Postolowski. Other states are taking a more aggressive approach. As of 2018, the state of Ohio inspects all of its 1,540 mobile home parks every year for habitability issues, according to Brandon Klein, speaking for its Commerce Department.

California’s housing department said it employs about 50 park inspectors, funded mainly through fees collected from park owners and residents. Between 2016 and 2019, the annual revenue for the inspection work averaged $8.2 million, according to the audit.

“The brutal reality of these parks is that California probably has one of the best systems in the country,” said Esther Sullivan, associate sociology professor at the University of Colorado, Denver, and author of Manufactured Insecurity: Mobile Home Parks and Americans’ Tenuous Right to Place.

How did things get so bad in Stockton?

Stockton Park Village stands out because its residents did file complaints. Heather Riley, her father’s staunch advocate, said she began flooding the state agency with them sometime in late 2019.

“I was calling everybody I could think of because at the time, his sewer was coming up into his yard,” she said. “So I was calling the county and…they routed me here and routed me there.”

As of late February of 2023, the state housing department had received 45 complaints with allegations about Stockton Park Village, although not all complaints were substantiated, according to Alicia Murillo, speaking for the housing department. CalMatters reviewed reports of most of those complaints and parkwide inspections at the park since 2017 obtained through a Public Records Act request.

Inspectors visited Stockton Park Village in February 2019, two months after receiving a complaint about a home that was disconnected from utilities and spilling raw sewage.

Over the course of four months — the statutory timeframe — the state sent multiple violation notices and warnings to the then-owners, the Fairbankses, for uninhabitable conditions in the unit. Then on June 19, 2019, it suspended their permit to operate the park. Two months later, after the issue was fixed, the owners got permission to start collecting rents again.

The same day an inspector recommended the state reinstate the Fairbankses’ permit, the state inspected the park again, in response to a new complaint about substandard conditions. State inspection reports show several of the park’s electric meters were missing, damaged, or without glass covers, which could spark a fire. The state also found evidence of squatters: Several extension cords criss-crossed the park, providing electricity to unpermitted RVs. The window and water heater vent for the laundry room were broken, and easily flammable junk, including brush and wood pallets, was piling up in the park.

The department issued various warnings until four months later when, with the problems still not fixed, it suspended the owners’ permit to operate on Jan. 10, 2020.

“We kept calling the state and having them come out and they didn't do shit about it.

THERESA KROP, 55-YEAR-OLD PARK RESIDENT

The permit suspension did little to stop the problems, and residents can keep living at the park during a suspension rent-free. Several complaints from early 2020 noted sewage leaks, broken security lights and power that surged on and off. Several people complained about the overflow of garbage. A complaint from the community development department noted the management office was boarded up and county officials were unable to get in touch with a property representative.

“We kept calling the state and having them come out,” said Theresa Krop, a 55-year-old park resident who has been living in the park since 2018. “And they didn't do shit about it.”

Krop said unlike for some of her neighbors, her travel trailer wasn’t her forever home: “But it was mine that nobody could take from me.”

On Feb. 6, 2020, while its permit was still suspended, the park was selected for its first parkwide inspection since at least 2014. Inspectors found many of the conditions the complaints described persisted, including broken windows in the laundry room, electrical hazards and plumbing problems, and sent off a new wave of warnings.

Still, on March 27, 2020, the state reinstated the Fairbankses’ permit to collect rent. It based its decision on the owners’ efforts to fix the problems and “personal assurances… the rental income would be used to support and pay for the remediation of the outstanding violations,” according to a court declaration by Krause.

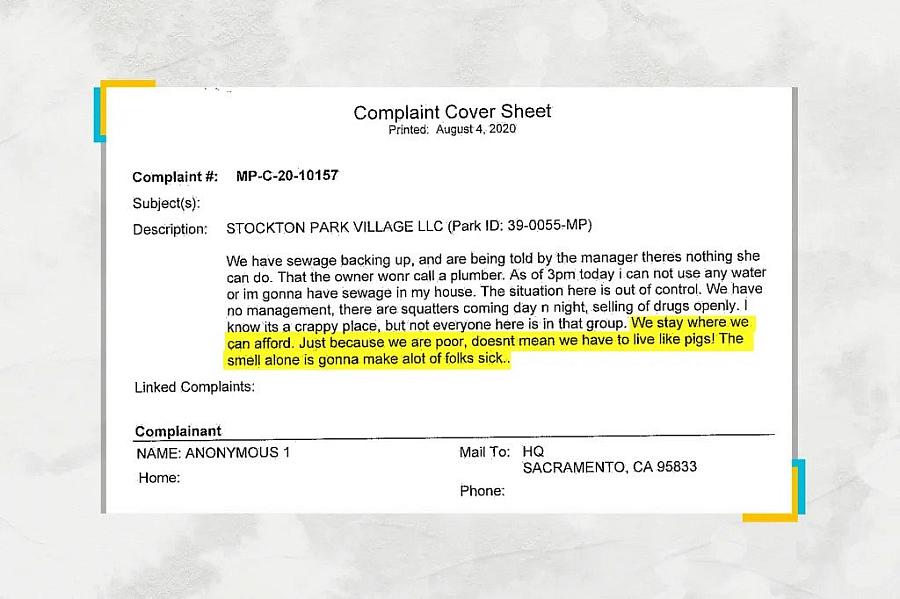

The problems didn’t go away. A July 31, 2020 anonymous complainant, for example, alleged they could have a sewage backup in their home.

“As of 3pm today i can not use any water or im gonna have sewage in my house,” they wrote. “The situation here is out of control. We have no management, there are squatters coming day n night, selling of drugs openly. I know its a crappy place, but not everyone here is in that group. We stay where we can afford. Just because we are poor, doesnt mean we have to live like pigs! The smell alone is gonna make alot of folks sick.”

An inspector closed the complaint file the same day because after driving through the park, the inspector couldn’t locate the sewage problem, and couldn’t contact the anonymous person complaining, according to the report.

Illustration by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

But on Nov. 15, 2020, the department suspended the Fairbankses’ permit to operate for a third time, in response to an earlier, similar complaint from May 2020, describing overflowing trash, dilapidated buildings and absentee management.

The permit suspension had little effect: Three months later, state inspectors found the septic drains and sewer pipes were broken and clogged, causing human waste to flow and pool across the park. The pile of trash had continued to grow out of control, eventually reaching 100 feet long and 8 feet wide — equivalent to a conga line of 10 elephants. It could, according to a July 2021 county inspection report, “potentially trap the residents living to the East of the Massive Trash Pile inside the Mobilehome Park." Dilapidated RVs and cars blocked the park entrance and exit for firefighters.

Since as early as 2019, county officials clamored for the state to intervene, said Merrill, the deputy counsel for San Joaquin County.

“We were trying to say to (the housing department) there are legal residents here who are truly suffering,” Merrill said.

Finally, in the summer of 2021, state housing officials sent a letter to the county requesting that the county district attorney initiate a civil action against the Fairbankses to abate the “imminent health and safety hazards” at the park. The county needed the letter, by law, to sue the park owners over the nuisance. After the Fairbankses failed to respond to the lawsuit, the county successfully petitioned the court to appoint a receiver, Merrill said. The judge on Sept. 1, 2021 transferred ownership of the park to Mark Adams, of the California Receivership Group.

Receivers are private companies that step into the owners’ shoes to resolve difficult code violations and in this case, ultimately sell the property. But Merrill and park residents said conditions did not improve.

“The receiver didn't have income to take any rehabilitative action,” she said.

The property was already so dilapidated by the time Adams took over, he said in a December interview, there wasn’t enough money to make the necessary repairs. Residents hadn’t paid rent in years, and with the permit still suspended, there was no new rental income.

Adams later would only respond in writing to submitted questions by CalMatters, citing a pending sale of the park for $455,000. He wrote:

(It) was two full months after the appointment before even initial funding of a mere $50,000 was approved. And then less than a month later, it was ordered that fully half of that initial funding had to be set aside for relocation assistance as opposed to cleaning up the park. Moreover, the City of Stockton and San Joaquin County Property Tax Collector have been adamant that their main priority is to collect their delinquent property taxes and delinquent utility charges, knowing that by doing so they effectively cut off any additional funding the Receiver could get to perform any abatement work and make the property safe for the people who live there… Since that time, no further funding has been approved for any purpose and indeed the only way the utilities were kept on even for a period of time was (California Receivership Group) advancing $23,000 of our own money. That has not happened in any other case I've been involved in over the last 22 years.

As of March 13, the buyer had not found a title company to insure the sale of the park because of its litigation history, according to a report filed to the court by the receiver. The buyer remains committed to the purchase, according to Drew Shane, speaking for Adams.

Merrill, from the county, is hopeful the new owner will bring the park up to code, but blames the state housing department for letting it get to a point where “it's almost not able to be rehabilitated,” she said in a January interview.

“At no point should any property under any jurisdiction get to the level of decay that (the housing department) allowed this to get to,” she said.

The state maintains it took “extremely strong enforcement action” in the park.

“If you look at it now compared to what it was, it's a night and day difference,” Krause said. “We have a good relationship and constant communication with San Joaquin County. And we've worked collaboratively with the county to get to this point.”

This January, by court order, officials from the county sheriff’s department finally cleared the squatters and garbage and barricaded the park’s empty lots, which also eased pressure on the sewage lines, Merrill said. Those last legal residents, many of whom are elderly and on a fixed income, have survived without water or electricity since January, according to Stephanie Ozomaro, who represents Riley and a dozen of his neighbors in the lawsuit. Riley depends on a generator to stay warm.

“When I moved in here, I thought, ‘This is where I’m going to end my days right here.’ And now,” Riley stammered, clawing for words as he looked around his cramped trailer.

“I'm still here but right now, I have no water. I have to buy, you know, cooking water. Everything I do I have to buy from the store, which, it ain’t that big a thing, but still, I’ve got to get water to bathe in, I can't shower, you know, no electricity. That's why I had to go buy that generator. You know, that cost me. Those things aren't cheap,” he paused, sighing. “It was either that, or freeze to death.”

Bobby Riley, 87, at his home at Stockton Park Village in the outskirts of Stockton on Jan. 27, 2023.

Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Data Fellowship.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Data Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by Cal Matters.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.