Newsom’s latest health care proposal includes more for middle and low income workers, less for those without legal status

California Gov. Gavin Newsom continued his rallying cry for universal health care Thursday with a revised budget that includes more subsidies for Covered California enrollees but doesn’t expand Medi-Cal to all undocumented adults, as some lawmakers are advocating.

On the campaign trail, Newsom came out in support of a single-payer system in which everyone is on the same government insurance. He has said that’s still the goal, but in the meantime he’s laying out smaller steps toward universal health care, the idea that everyone has coverage they can afford.

That plan remains a focus area in the governor’s latest budget proposal, released Thursday. It includes a fine for Californians who don’t carry insurance to replace a similar federal policy that the Trump administration ended in 2017. Newsom says he’ll use the revenue from the penalty to make insurance more affordable for people who struggle to pay for plans on Covered California, the state’s insurance marketplace created under the Affordable Care Act.

The absence of an insurance mandate could lead 300,000 California consumers to flee the individual insurance market, including as many as 250,000 people insured through Covered California, according to estimates by the California Association of Health Plans. Experts say fewer people means a less diverse risk pool, which raises costs for everyone.

The policy change is already having an effect — Covered California showed a 24 percent drop in the number of new enrollees from 2018 to 2019.

“Without a mandate, you will see an increase in your premiums — every single person in this room and everybody watching,” he said. “I’d like to avoid that.”

Newsom said Thursday that the mandate, if passed in the Legislature, would generate roughly $330 million a year, down from the $500 million in annual revenue he estimated in January. He says that money will help subsidize premiums for people on the Covered California exchange.

In the January budget, Newsom proposed creating state subsidies for individuals making 250 percent to 400 percent of the poverty level, or between $30,000 and $49,000 a year. Now, he says people making as little as $24,000 will also receive a boost. The state credits would be in addition to federal subsidies.

His proposed expansion also extends assistance to individuals earning up to $73,000 a year, or 600 percent of the federal poverty level, who don’t currently get federal subsidies. California would be the first state to make this change, though Minnesota had a temporary program to help this group in 2017 according to Laurel Lucia, health care program director with the UC Berkeley Labor Center.

Christen Linke Young, a fellow with the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy in Washington, D.C., called it “an incredibly exciting piece of policy” for improving affordability, though she noted it would be tough to execute.

“It’s hard to put together a tax credit that sits on top of the federal tax credit in this way,” she said. “The system requires a high degree of operational excellence from Covered California and the tax agency in California … it is operationally complicated, and it certainly is something policymakers should have front of mind.”

Anthony Wright, executive director of the consumer group Health Access, said in a statement that the revenue from the mandate could help California’s low- and middle-income families who “are still living one emergency away from financial ruin,” but added that more is needed.

"We will continue to work with legislators to … have a more meaningful impact on those who don't get ACA subsidies but still struggle with the cost of care given our high cost of living,” he said.

The new subsidies would go into effect for calendar year 2020, the first year the state penalty would be imposed. But Keely Bosler, Newsom’s director of finance, says penalty revenues won’t come in until 2021, so general fund dollars will be used at first. The subsidies would expire in three years.

Wright’s “Care4All California” coalition is pushing a package of 22 bills this year, including two that would create the individual mandate and several others that would further subsidize insurance costs.

The group also wants to see Medi-Cal, the state version of the federal Medicaid program that provides free or low-cost health insurance to those with limited incomes, expanded to all undocumented adults in the state who qualify based on their incomes. But on Thursday, Newsom reiterated plans to extend Medi-Cal eligibility to undocumented people up to age 26 — undocumented children 18 and under are already eligible.

In the January budget proposal, Newsom estimated that covering the young adults would cost $260 million. This week’s version allocates just $98 million for this purpose.

The governor says he originally estimated that 138,000 people would benefit from the expansion, but his latest estimate puts it closer to 106,000 people. The revised budget states that the expansion will provide full-scope coverage to approximately 90,000 undocumented young adults in the first year, and that nearly 75 percent of these individuals are currently in the Medi-Cal system.

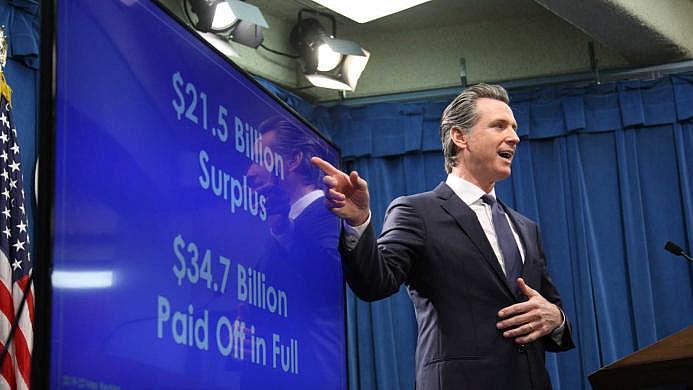

“It’s fully funded from our perspective, and we are fully committed to implementing it,” Newsom said. “Those numbers reflect a different reality. Rather than having a surplus, I’d rather be more honest going into the budget.”

Some Republican lawmakers say Newsom is overspending in his May revision.

“In the last decade, California’s state budget has more than doubled,” said Republican Assemblymember Vince Fong of Bakersfield. “Even with a budget surplus, the governor has the audacity to propose even more taxes instead of returning it to hard-working Californians [who] earned it. Californians are rightfully fed up with the insane cost of living and working in this state.”

Newsom insists that the individual mandate is not a tax.

He says he’s not proposing a Medicaid expansion to all undocumented Californians due to the cost, which he estimates at $3.4 billion.

“If you’re curious why I can’t include it in the May revise, there’s 3.4 billion reasons why it’s a challenge,” he said.

But he noted that the Legislature “may have new strategies, new approaches,” and that he’s willing to listen.

Elia Gallardo, director of policy research for the nonprofit group Insure the Uninsured Project, said this is an important first step.

“Health care access to ensure primary, preventative health care access to any population group is important and critical in order for them to maintain their health as they age out,” she said. “As proponents of universal coverage, we’d like to see all the remaining uninsured covered.

This proposal is the latest in a yearslong fight by universal health care advocates in California. Democratic lawmakers requested $1 billion last year to make these and other changes, but then-governor Jerry Brown did not set aside money in the budget, citing the need to build up the rainy day fund.

Newsom wants to create a Healthy California for All commission to take a deeper look at ways to expand affordability and access.

In the meantime, the governor’s budget revision allocates money to bolster the safety net for the uninsured and underinsured. He’s called for adding $20 million to the originally proposed $100 million for programs for homeless individuals in need of health care. He’s also pitching more health funds for counties, and an additional $100 million in workforce training to combat the state’s shortage of mental health professionals.

Follow the USC Center for Health Journalism Collaborative series "Uncovered California" here.