One of the worst in state. Merced County’s childhood obesity crisis

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Vikaas Shanker, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Childhood obesity: Do Merced schools provide too much fruit juice, chocolate milk?

Childhood obesity: Here’s what’s being done in Merced County

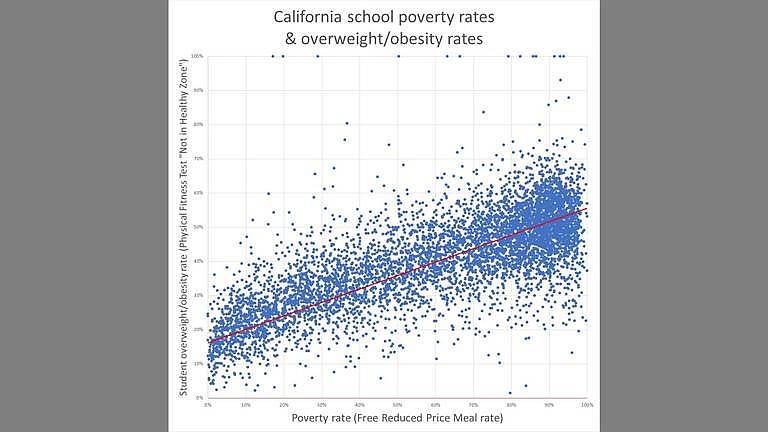

This scatter plot graphs the student poverty rates and overweight/obesity rates for thousands of California schools.

VIKAAS SHANKER GRAPHIC/VSHANKER@MERCEDSUNSTAR.COM

When family medicine Dr. Abhilasha Sharma looked at Christina Almanza’s pre-checkup adolescent survey, she noticed her 16-year-old Merced patient’s weight had increased 15 pounds since her last visit.

“We need to look at that,” Sharma said as she prepared to conduct a checkup, concerned because Christina was also diagnosed as pre-diabetic in prior checkups.

Christina Almanza’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

The teen’s body mass index, or BMI, was in the 94th percentile, pushing her into the “overweight” range. And while BMI isn’t always the best measure overweightedness or obesity, Christina’s body composition confirmed it was accurate, Sharma said.

But Christina, a Latina high school student on MediCal in Merced County, is not alone, by far.

A Sun-Star analysis of obesity and demographic data from thousands of schools in the state show that low income and Latino students are at a substantially increased risk of developing obesity.

One of every three children under 18 years old in Merced County is living under the poverty line, and almost three of every four Merced County kids are Latino, according to U.S. Census and state data.

So perhaps it’s not surprising Merced County has one of the highest childhood obesity rates in the state. Researchers and health officials are calling it an epidemic.

Almost half of Merced County elementary, middle school and junior high students are either overweight or obese, according to an analysis of 2018 body composition measurements in physical fitness testing data collected by the California Department of Education.

That’s more than twice the national average. And it lands Merced County with the eighth highest student obesity rate in the state, behind Imperial, Colusa, Glenn, Mendocino, Monterey, Kings and Tulare counties.

But what puts Merced County in dire straits is the fact that only one of these counties, Tulare, has a higher child poverty rate and Latino student ratio.

While poverty and ethnicity are not the only markers of childhood obesity, there are strong correlations according to data analysis and several health officials and researchers.

Childhood obesity rates in schools increase as student poverty rates increase, according to the analysis. Schools with higher Latino student ratios are more likely to have higher obesity rates as well.

Among the 10 non-county schools in Merced County with the highest overweight-obesity rates, seven have Free and Reduced Price Meal, or FRPM, rates of more than 80 percent. FRPM rates have been widely used as an imperfect but relatively reliable measure for student poverty.

Of the 10 schools with the lowest FRPM rates, just two schools have overweight-obesity rate of more than 50 percent.

HEALTH EFFECTS

Back at the Golden Valley Health Center checkup, Christina was reserved and quiet as Sharma asked her about her eating patterns. Christina’s mother told Sharma about how her daughter’s behavior and eating patterns have changed.

The teen stopped eating breakfast. So Sharma assigned her a health educator who will help not only Christina, but her family, to maintain a healthier weight as a preventative measure against Type 2 diabetes.

In addition to Type 2 diabetes, obesity is a major risk factor in a slew of metabolic disorders and diseases, including heart disease and sexual health issues, according to the CDC. But obesity can also lead to breathing problems, psychological conditions like anxiety and depression, low self-esteem and social issues like bullying.

The number of people with Type 2 diabetes has steadily increased over the past ten years in Merced County to the point one out of every 11 adults over 20 years old has it, according to CDC data.

When weight, and more importantly body fat composition, starts becoming a problem in children, it amplifies the risk they will develop conditions like Type 2 diabetes, experts have said.

Christina and her mother were both overweight. So during Christina’s checkup, Sharma made it a point to emphasize the importance of a good diet to both of them.

“When a kid walks into the room, I look at who else is walking in: parents,” Sharma said. “The problem may be with the entire family so we concentrate not just on health education for the child, but for the entire family.”

It’s not uncommon for the entire family to not be educated in how to look for and get healthy foods, Sharma said.

“I tell the parents I want the kid to come in with whoever the kitchen manager is, whoever is cooking or bringing meals or food for the family,” Sharma said.

ECONOMIC, RACIAL DISPARITIES

But it’s hard to blame families and individual Latino and lower income family kids when the odds are stacked against them, said Susana Ramirez, a researcher with the UC Merced Public Health department.

“Obesity is a bigger problem here,” said Ramirez, whose research focuses on obesity issues in Latino populations of the Central Valley.

“Healthy foods are often not available or affordable for low income populations while unhealthy junk foods are easily available and affordable,” she said.

A January report by the Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity found that processed food-related companies increased targeted TV advertising in the United States to Hispanic and black children by 8 percent from 2013 to more than $1 billion in 2017.

Nestle targeted the most brands to Hispanic children while McDonald’s spent the most on TV ads at $58 million. General Mills’ Big G cereals, Kellogg’s Pop Tarts, Extra Gum and Kellogg’s Special K brands each spent 40 percent or more of their TV ad budgets on Spanish programming, the report said.

Most of the healthier and fresh food options are in the northern, more affluent parts of Merced, Ramirez noted, while most of the fast food restaurants and processed food sources are in the southern, less affluent half of the city.

Local health officials in 2017 analyzed seven neighborhoods in Merced County, including in Merced, Winton, Los Banos, Livingston and Dos Palos, and found there were more fast food restaurants and convenience stores selling unhealthy options than grocery stores and farmers markets with more nutritious food.

Survey research also shows that the higher price of healthy foods leads to consumption of less nutritious options.

For kids, it’s easier, quicker and more tasty to pop into a convenience store for a bag of chips, or head to a fast-food restaurant after school, rather than get nutritious fruit or a salad, experts have said.

Another issue adding fuel to Merced County’s obesity epidemic is the 2018 U.S. Farm Bill, according to Dr. Dean Schillinger, a former chief of the Diabetes Prevention and Control Program at the California Department of Public Health.

The Farm Bill, a $867 billion apportionment that shapes food, farms, agriculture and rural areas, benefits Central Valley farmers by incentivizing them to grow commodity crops like corn and wheat over vegetables.

But by doing so, it also drives down the ingredient prices of the wrong foods processed foods and sugary drinks instead of whole foods that provide better nutrition, said Schillinger, who is currently chief of the UCSF Division of General Internal Medicine at San Francisco General Hospital.

Latino families and children are more likely to be food insecure and are more often on food assistance and donation programs due to their higher poverty rates, according to Ramirez’s research.

“They are more likely to live in communities where it’s harder to access healthy foods. And they are more likely to be disproportionately targeted for advertising of fast food restaurants, soda and highly processed foods at a kid’s eye level.”

Ramirez’s study of Mexican-American women in the Central Valley also shows a cultural barrier to fighting obesity called dietary acculturation paradox.

Many of the women in the study were proud of their food and culture, but they also thought their traditional foods were unhealthy. And as they shifted to a mainstream “healthier” American diet, they were more susceptible to buying and cooking processed, less nutritious foods.

“It’s a very complex issue,” said Dr. Katie Meyer, a Merced pediatrician who is part of a statewide coalition to help combat childhood obesity. “It’s different with every kid, but for a lot of kids it’s the sugar, sugary drinks. There’s tons of that, even just too much juice.”

And in some communities, being a big kid isn’t often considered a bad thing, Meyer said.

“We see that within the Hispanic/Latino population, a lot of people see a chunky, roly poly baby or kid and thinks ‘cute,’” Meyer said. “People don’t see obesity as an issue until they start having complications (later in life) … But when a child is 7, people have a hard time seeing it’s important to change those behaviors, dietary routines, and it’s difficult to get families and kids on board.

[This article was originally published by the Merced Sun-Star.]