Part 3: Hospitals Try to Balance Care, Financial Constraints

This story was produced as part of a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Part 1: Bottleneck in Psych Care Leaves Hospitals, Patients in the Lurch

By Jared Whitlock

Earthquake regulations with a 2030 deadline led Scripps Health to reimagine its Hillcrest campus. They also forced a reckoning in behavioral health.

Scripps is planning a 15-story tower to replace Scripps Mercy Hospital, including a locked psychiatric ward with 36 beds.

It was estimated a replacement behavioral health facility attached to Scripps Mercy would cost $3 million to $4 million per bed, according to Scripps, a costly proposition.

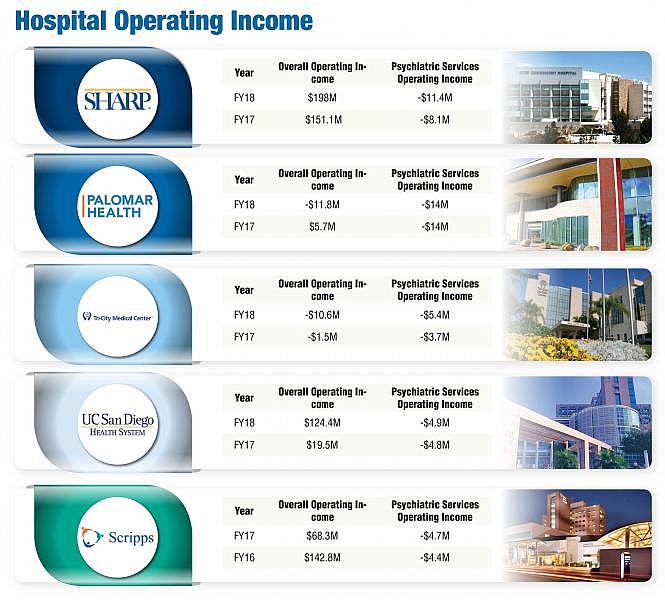

And operations lose money. Scripps lost $4.7 million on psychiatric services in 2017, similar to the two prior years.

Making behavioral health pencil out has become a greater challenge for San Diego hospitals like Scripps, Sharp HealthCare, Palomar Health and UC San Diego Health. Partly for fiscal reasons, Tri-City Medical Center last year suspended inpatient beds.

Answers to the financial puzzle may lie in partnerships, a federal announcement in November that cleared a path to use Medicaid dollars for larger psychiatric facilities, and care centers that can act as an alternative to locked inpatient wards.

In recent years, financial and regulatory pressures strained the region’s behavioral health system. It’s to the point where patients in emergency rooms and inpatient beds sometimes face long waits for the next stage of care.

The Partnership Path

Rather than the $3 million to $4 million per bed plan, Scripps Health decided partnering would be the best route. Under a deal announced in February, the health system and Acadia Healthcare plan to develop a 120-bed psychiatric inpatient unit by 2023.

“I think this entire community understands the great need for more inpatient beds,” Scripps CEO Chris Van Gorder said.

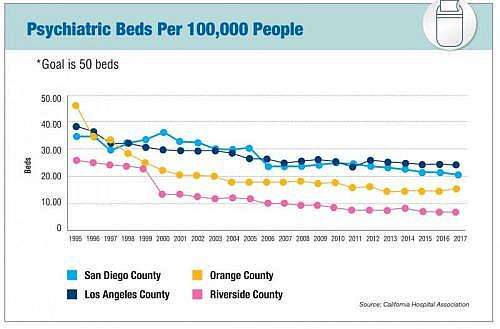

San Diego has about 700 inpatient beds, down 30 percent from 1999, a trend that also played out in Los Angeles, Orange County and Riverside, according to data from the California Hospital Association. Meanwhile, hospitals reported increases in emergency psychiatric volumes, creating a supply-demand imbalance.

Scripps would have a 20-percent ownership stake in the new hospital, which would be in Chula Vista due to land constraints in Hillcrest.

Van Gorder said not only would the deal free up funds for other construction projects, but also aims to eliminate Scripps’ annual losses in behavioral health. Acadia would have the scale, expertise and patient mix to make the venture profitable, he added.

He noted that Acadia will honor Scripps’ charity care policy, namely taking low-income patients with Medi-Cal.

Tennessee-based Acadia, a for-profit provider, is a powerhouse with 586 behavioral health facilities. In 2016, the company embarked on a strategy of partnering on facilities with not-for-profit hospitals like Scripps, attracting them with the promise of allaying patient backups in emergency rooms.

But Acadia has come under scrutiny in several communities, including lawsuits in Oklahoma over patient injuries, highlighted by The Oklahoman newspaper.

Van Gorder said Scripps conducted “significant due diligence.” He also noted that Scripps will be part of the facility’s joint operating group, having say over who the chief executive and chief medical officer will be, and other key decisions.

“I think you can almost look at any major health care system, including some of the named organizations around the country, and you’re going to be able to dig up some problems that they’ve have had clinically or operationally,” Van Gorder said. “We looked at them and were comforted by our due diligence.”

In the vein of the Scripps and Acadia tie-up, Palomar Health, the county and an unnamed partner are exploring building a behavioral health unit with some 70 inpatient beds. This would replace Palomar’s existing 22-bed facility.

“We’re working with an organization that does this across the nation to figure how we can, not necessarily make a margin on this hospital or within this population, but how do we minimize the cost to us on an annual basis?” Palomar Health CEO Diane Hansen said.

She added: “This is definitely a loss leader for us. But the reality is that it’s part of our mission.”

In 2018, Palomar reported about a $14 million loss on psychiatric services. This swung the company into the red. Palomar posted an overall operating loss of $11.8 million.

(Photo by Stephen Whalen) Nurses huddle at Alvarado Parkway Institute’s inpatient behavioral health unit. Alvarado has also invested in residential crisis centers that can be an alternative to inpatient care.

More Holistic Care?

Despite a hit to one area of the bottom line, hospitals have more incentive to invest in psychiatric care, said Lindsay Scollin. Payment models increasingly emphasize patient outcomes.

“Organizations are starting to think about care of the patient more holistically,” said Scollin, a senior manager with consulting firm Deloitte. “They see mental health as an area they really need to invest in or they’re going to have longer-term implications.”

They aren’t only pouring money into facilities. Scollin said hospitals have turned to telepsychiatry and other technology, despite reimbursement being slow to catch up.

Dr. Michael Plopper agreed that it makes business sense to treat the whole patient, and he said it’s the right thing to do. He’s the chief medical officer of Sharp HealthCare, which among San Diego hospitals carries the greatest load in behavioral health with 200 inpatient beds.

In San Diego, financials show fatter margins among larger hospital systems like Sharp HealthCare, cushioning deficits in behavioral health.

Sharp HealthCare in 2018 said it lost $11.4 million on psychiatric services. Despite this, financials show $198 million in overall operating income.

But Plopper said it’s unsustainable for hospitals to hemorrhage millions annually in psychiatric care, even if profitable today.

“They (hospitals) really can’t go forward on a long-term basis with operations that chronically lose large amounts of money, because we aren’t always going to have a great profit at the end of the year. It’s a huge issue for us as well as other facilities,” Plopper said.

Reducing Pressure on Hospitals

As one solution, he said the financial picture would improve if hospitals get the okay to use Medicaid dollars for mental health treatment in facilities with more than 16 beds.

This was barred in many facilities under a 1965 decision intended to prevent the warehousing of patients. But acknowledging a dearth of inpatient care, in November the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced it would let states apply for waivers.

The agency said communities must also flesh out a continuum of care, an area where San Diego struggles, despite increased county funding.

Local Medi-Cal patients in locked psychiatric wards who need continuing care — such as an assisted living facility — wait on average two weeks, the San Diego Business Journal detailed in the first part of this series.

That’s the result of fewer licensed community homes providing step-down care, a function of expenses outpacing reimbursement.

“If we can build that out and provide that continuum of care, I think we can dramatically reduce the pressure on hospitals,” said county Supervisor Nathan Fletcher.

Upon his recommendation, the San Diego County Board of Supervisors is looking at turning a county-owned property in Hillcrest into a behavioral health hub. It would take patients discharging from two nearby hospitals, and provide other services as well.

Fletcher said the idea is modeled after programs like one in New Haven, Connecticut targeting high hospital readmissions. He added there’s early talk of establishing hubs in additional parts of the county, possibly involving nonprofits.

In San Diego, mental health was thrust to the fore last year when Tri-City Medical Center suspended its 18-bed behavioral health unit. Although a relatively small share of regional beds, other hospitals noted the pressure of added patients in recent months.

Tri-City’s decision came after federal regulations required the hospital to bring psychiatric buildings up to code, including new ceilings to reduce the risk of patient hangings. Retrofitting would cost upward of $7 million, according to media reports.

The federal requirements were “not only costly and disruptive, but could not be completed in a timely manner in order to comply with federal patient safety regulations,” the hospital said in a statement. It also cited a national shortage of psychiatrists as a factor, as well as low mental health reimbursement.

Tri-City said these and other issues need to be addressed before the health system considers resuming operations of the inpatient unit.

Tri-City posted a $10.6 million operating loss last year, and of that was a $5.4 million loss on psychiatric services.

Similar to Scripps, redevelopment plans at UC San Diego Health’s Hillcrest campus look to impact its psychiatric facility. Asked whether the health system would maintain or expand bed capacity, UC San Diego issued a statement.

“UC San Diego Health is committed to caring for patients in need of all phases of psychiatric care. Our future Hillcrest campus will provide an array of outpatient services as well as inpatient care to those in need of behavioral health services,” adding that care wouldn’t be interrupted during the redevelopment.

In late 2018, the health system also signed a memorandum of understanding to manage all or part of the county’s psychiatric hospital on Rosecrans Street.

Alvarado Parkway Institute operates 66 inpatient beds, and because of the steep costs to add more, the hospital has invested in residential crisis centers.

That includes Alvarado’s Jackson House, opened in 2017 for patient care in an environment notably more relaxed than an inpatient ward. Patients prepare meals and use computers to job hunt, in a building that was once a bank.

With fewer regulations than inpatient wards, it’s less costly to operate.

While Jackson House has round-the-clock nursing, the facility can only take less-acute cases. Alvarado officials said it’s one solution, in an area demanding many.

[This story was originally published by San Diego Business Journal.]