In Puerto Rico, Calling 911 in a Mental Health Crisis Can Get You Tased

The story was originally published by the MindSite News with support from our 2023 National Fellowship's Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Illustration by Josué Oquendo Natal

The story has been updated with responses from the Puerto Rico Police Bureau in the 13th and 14th paragraphs.

When Roxana Sánchez Pérez saw her husband, Iván Lourido Alverio, break the mirror doors of a small closet in their home in Morovis, Puerto Rico, she knew it was time to seek help. It wasn’t the first time that Lourido Alverio, who has a history of depression and anxiety, suffered an apparent mental health crisis. In the past, these episodes had become so severe that they required at least three hospitalizations in psychiatric units.

That time, Sánchez Pérez did not seek help from a mental health professional, but instead followed the usual protocol in Puerto Rico: She went to the nearest police station and told the agents there what was happening at home. She told them she feared for her safety and urgently needed “a 408,” as most people refer to the court order that gives authorization to involuntarily commit someone experiencing a mental health crisis to a hospital.

That night of Feb. 11, 2020, Sánchez Pérez returned to the home she shares with Lourido Alverio and the couple’s grown daughters, accompanied by five uniformed police officers. The agents arrived at the Morovis neighborhood in patrol cars to enforce the order issued by an Arecibo Court judge. Lourido Alverio, 42, was to be transferred to a hospital to receive psychiatric care.

After an hour and a half of trying to get the man, who was locked in the house, to calm down, the police used a Taser on him to carry out the judge’s order.

“I heard him shouting: ‘You’re going to kill me; you’re going to kill me.’ He screamed: ‘it hurts,’” Sánchez Pérez, Lourido Alverio’s wife, recalled in a recent interview about the incident. Her husband ended up in a hospital in Manatí where a doctor had to remove the Taser darts that were stuck in him. They were embedded in his right knee and the left side of his waist. From that hospital, he was transferred again by ambulance to another institution — this time, in San Juan — where he finally began receiving the mental health care he needed.

The experience of Sánchez Pérez, who waited outside her house as she heard the agents intervening with her husband, and that of Lourido Alverio, who has since resumed his psychiatric treatment, is not unusual in Puerto Rico. The Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) quantified, reviewed, and analyzed hundreds of Puerto Rico Police use-of-force reports from incidents between 2018 and 2021 in the San Juan and Arecibo regions, and found that 23% to 30% of these interventions happened against people who were suffering an apparent mental health crisis. In more than half of these cases, the agents used a Taser, which has been shown to present a health risk to the person being shocked and, in some cases, has caused death.

In 2011, the United States Department of Justice concluded that the Puerto Rico Police Bureau systematically and repeatedly committed civil rights violations, including the excessive use of force. In response to these findings, which confirmed what civil society organizations had denounced for years, the federal and Puerto Rican governments agreed in 2013 that the Police Bureau should carry out a comprehensive reform. The reform seeks to transform the training offered to officers and requires agents to improve how they collect and report information about interventions.

It has been 10 years since the reform began under the supervision of the U.S. District Court in Puerto Rico, and changes are moving slowly, despite the $20 million in public funds that the government of Puerto Rico allocates to the reform annually. Last September, U.S. District Court Judge Francisco Besosa, who oversees the reform case, ordered the Puerto Rico Police Bureau to adjust its strategy because, after a decade, “monumental changes remain to occur.”

“The Court finds the pace at which the reform is progressing less than acceptable,” Besosa stated in an order dated Aug. 17, 2023. He also criticized the bureau because, according to the most recent findings by the federal monitor supervising the reform, the police are still not complying with 56 of the 179 most important changes they agreed to make.

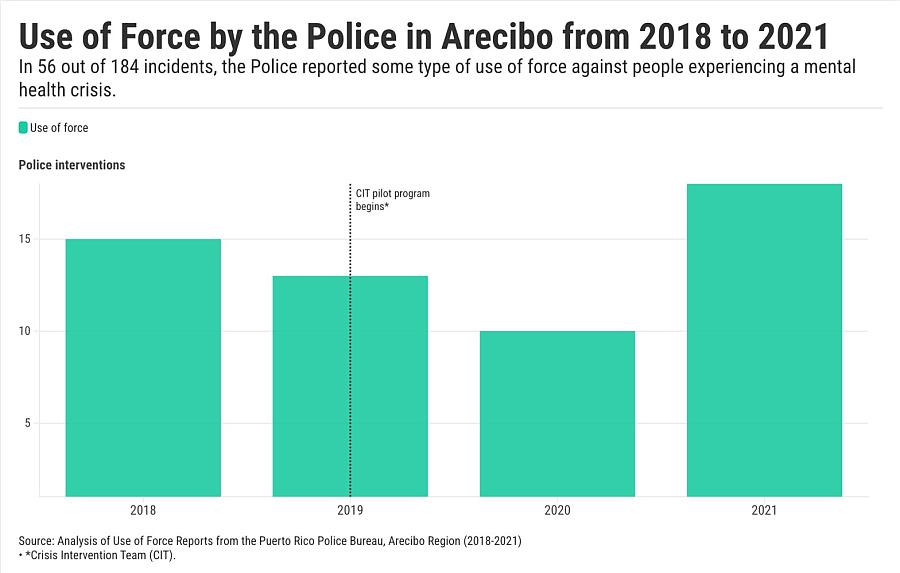

One area where the bureau remains out of compliance is with the intervention strategies it uses with mental health patients. The police launched a pilot project in the Arecibo Region in 2019 using a model developed in 1988 in the U.S. known as Crisis Intervention Team or CIT. Participating police officers receive 40 hours of training that seeks to sensitize them to the needs of a person experiencing a mental health crisis and provide them with de-escalation tools. In some jurisdictions, these programs also involve mental health and community professionals, but the Puerto Rico project is staffed only by police officers.

“As an agent, I’m not a mental health professional, but [with this training] I have some criteria to see how I’m going to work with that person,” Police Sergeant Thayra Negrón Meléndez, coordinator of the CIT pilot program in Arecibo, said in an interview. “Before the [CIT pilot] program, excessive force was used. There was even the use of firearms. That has already been limited.”

This group of police officers is part of the special team created in the Arecibo Region for a pilot project to train a select group of officers on strategies to manage interventions with people experiencing a mental health crisis.

Although the CIT pilot program officially ended in 2020, Negrón Meléndez said she and her team of 11 officers from the Arecibo Region of the Puerto Rico Police continue to work as a specialized group. Since the program’s implementation, most interventions with mental health patients in that region end without use of force, Negrón Meléndez said.

In an effort to learn about the performance of the pilot program, CPI requested an interview with Commissioner Antonio López Figueroa and other senior representatives, but the officials did not respond. The bureau also did not immediately respond to written questions submitted by CPI. Damarisse Martínez, press officer for the bureau, said in an email that the CIT program is still in place, and that “the Puerto Rico Police has been proactive and has trained all of its personnel…in the correct interaction and management of people suffering emotional or mental health crises.”

In his eighth report published in June of this year, Police Reform monitor John Romero stated that although the CIT pilot program officially ended in November 2020, the Puerto Rico Police still had not provided the court with a final evaluation of the program three years later.

Police Reform monitor John Romero, with federal judge Francisco Besosa, Alexis Torres, secretary of the Department of Public Security, and Antonio López, commissioner of the Police Bureau.

Photo taken from the Dept. of Public Safety’s Facebook page.

“The Bureau has lagged in its efforts to complete an evaluation of the pilot program and expand it to other areas of the island,” Romero said in his most recent report. The bureau’s spokesperson said in her written statement that, to this day, there are 73 CIT-trained officers in Puerto Rico.

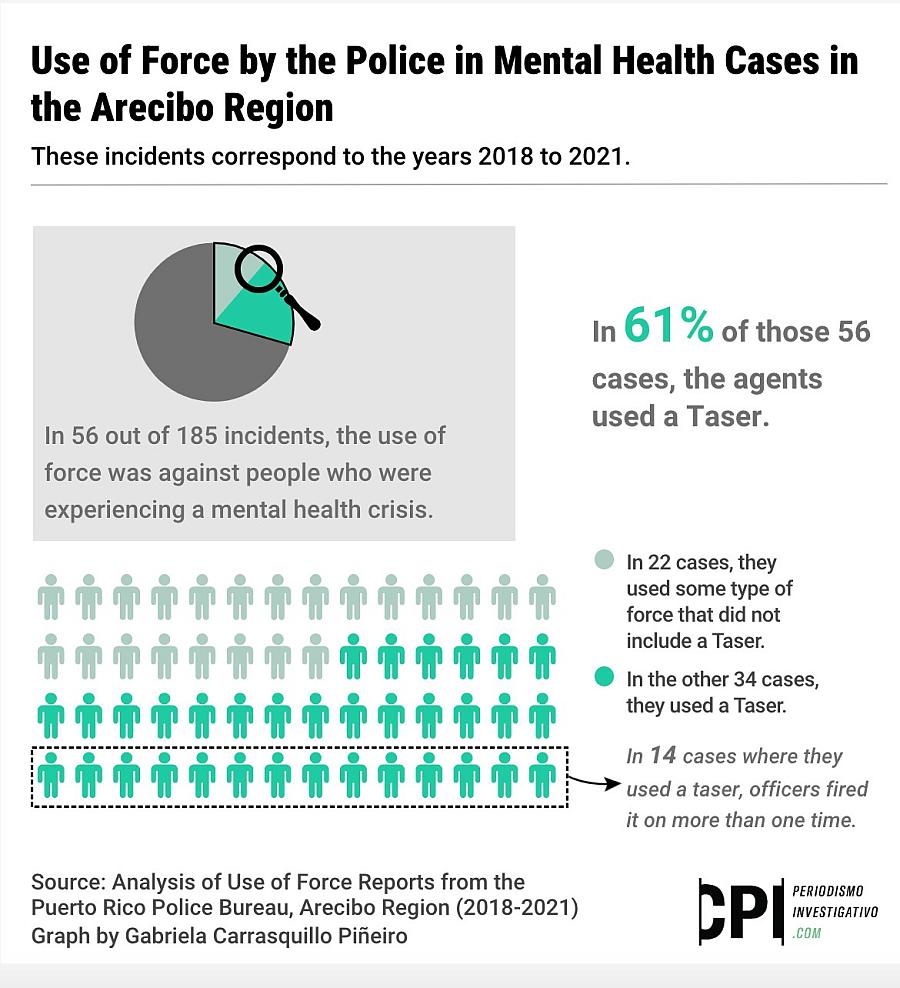

For this investigation, CPI analyzed use-of-force reports from the Arecibo Region between 2018 – before the CIT pilot program – through 2021, when it had officially ended, but, according to Negrón Meléndez, remained in operation. Of the 185 incidents in which the Arecibo Police reported using some type of force during those four years, 56, or 30%, were against people who were experiencing a mental health crisis.

In 61% of the incidents in which force was used against people experiencing a mental health crisis, officers used a Taser or, as they call it in their official reports, an electronic device. Thirty-four people in the Arecibo Region received at least one electric shock from police while suffering a mental health crisis. One of them, late that night in February 2020, was Lourido Alverio.

Agent Joel García Echevarría, the CIT team member who fired the Taser at Lourido Alverio, wrote in his use-of-force report that officers spent about 90 minutes trying to get him to come out of the house before they went inside.

Lourido Alverio then came out of a bedroom “aggressive, shouting insults, using foul language, and uncooperative,” the officer wrote. “He got too close to me [and] I made the determination to use the control of the electronic device, to safeguard his life and my safety.”

This was at least the third time during the period from 2018 to 2021 in which García Echevarría took part in an intervention that included the use of a Taser on a person experiencing a mental health crisis.

García Echevarría’s version contradicts the account given to CPI by Sánchez Pérez, the wife of Lourido Alverio. She was positioned outside the front door when he was tasered. According to her, police entered by surprise, Lourido Alverio walked to a closet to get a towel, and García Echevarría then fired the Taser darts at him. The shock caused Lourido Alverio to fall to the floor in front of the closet, which is about 12 feet away from where she said the officer was standing.

“I heard the blow when he fell to the floor, and I was near the window when he was shouting: “You’re killing me, you’re killing me,” Sánchez Pérez said. “Then they took him out handcuffed, with those two darts stuck in him, one next to his belly button and the other in his leg.”

The Taser, a misleading weapon

Today, Tasers are everywhere. Virtually every police department in the United States uses them, Michael White, a criminal justice professor and researcher at Arizona State University, told CPI in a recent interview.

Professor Michael White of Arizona State University says that Taser discharges not only cause immense pain, but can essentially paralyze a person while the electric current is active.

Photo by Charlie Leight | Arizona State University

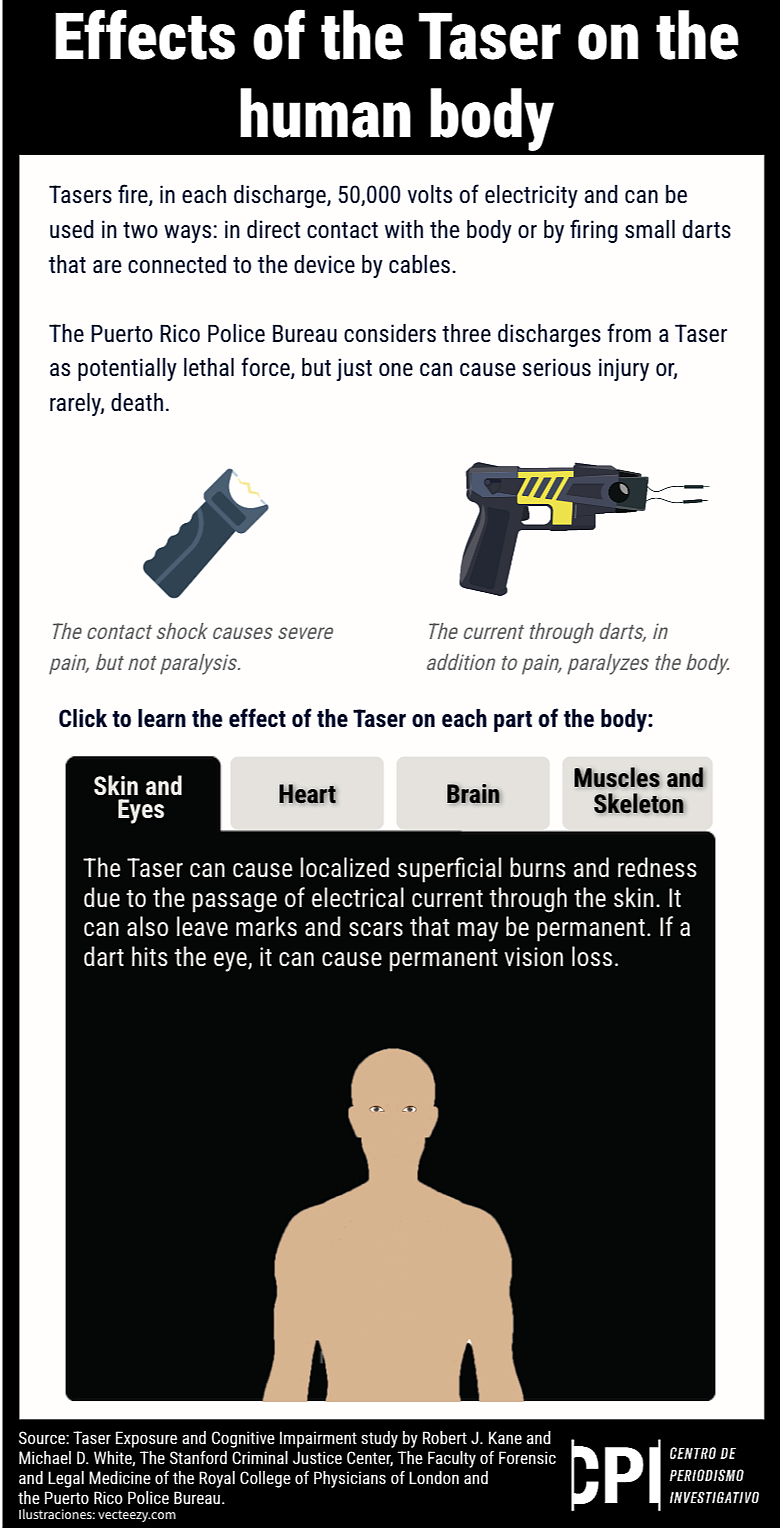

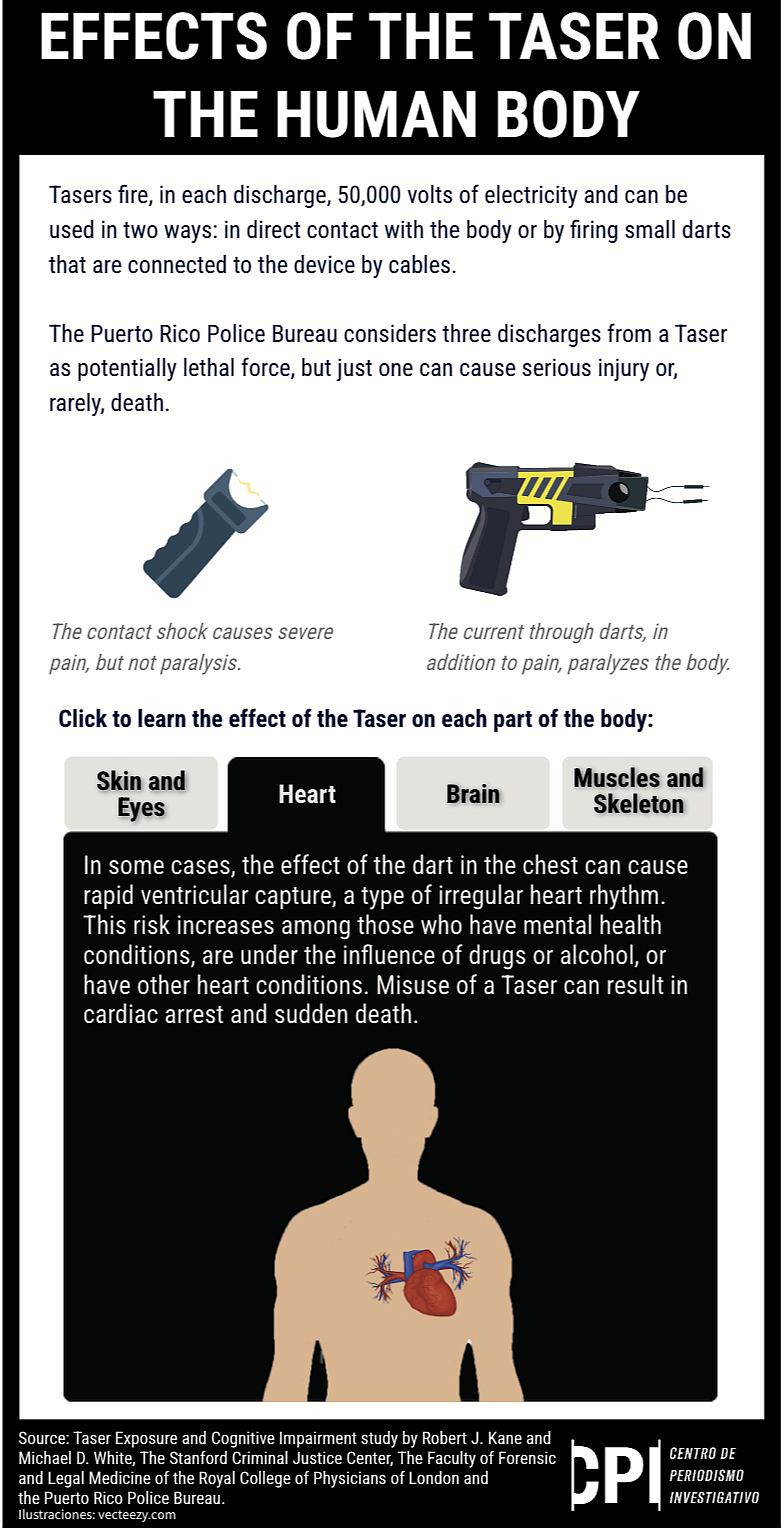

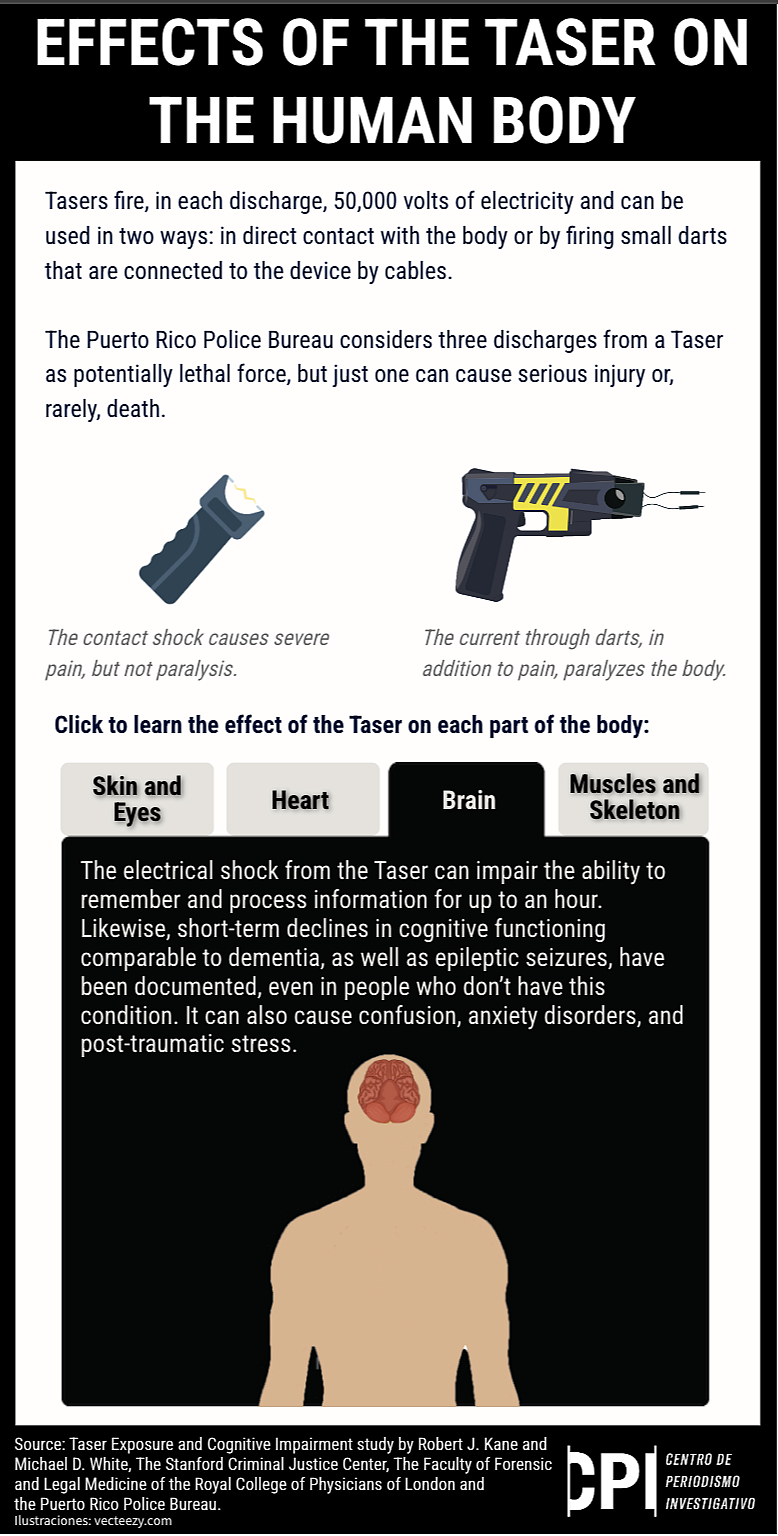

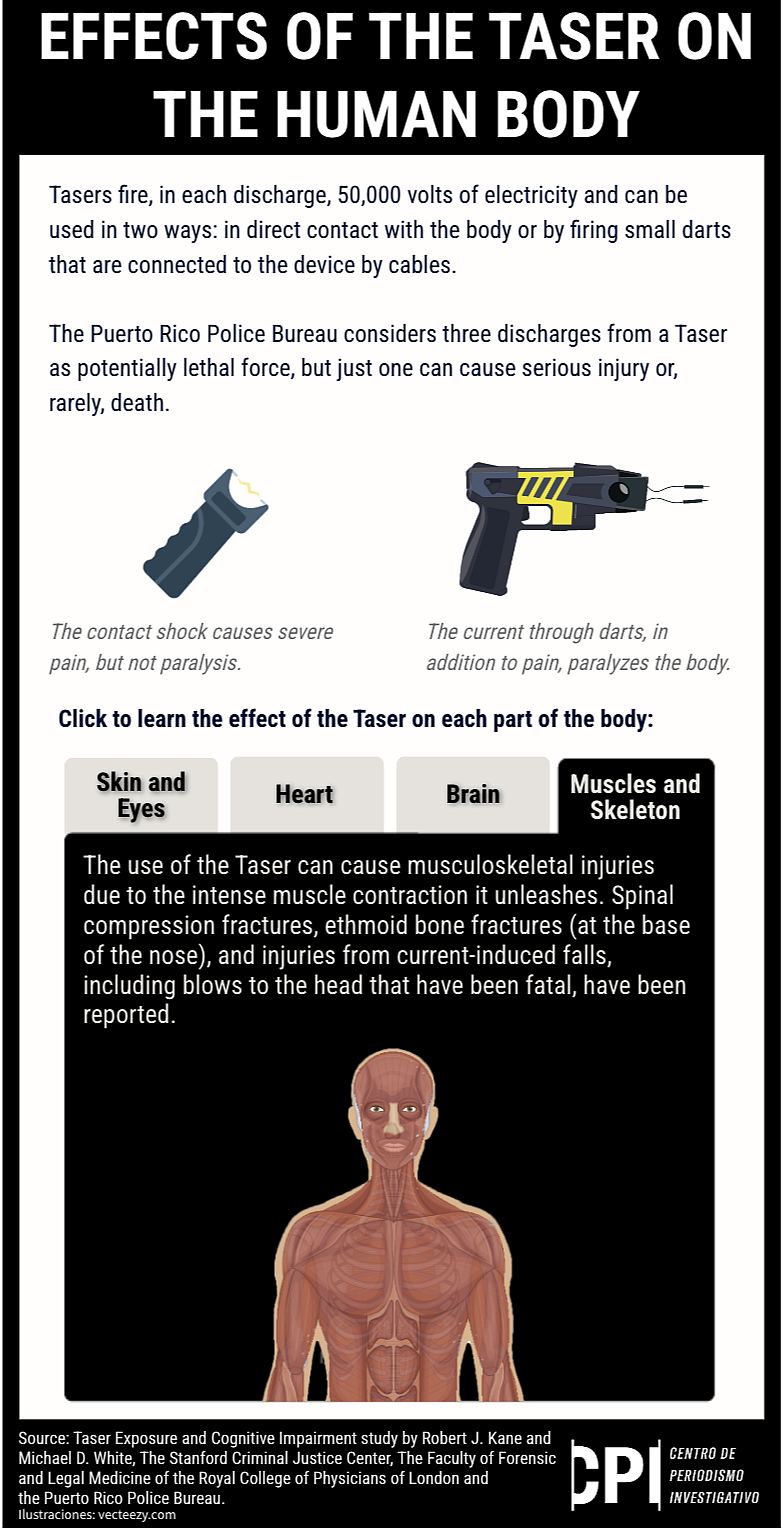

While many believe that Tasers are harmless weapons, the electric current they discharge can have serious health consequences and even be fatal. Academic studies and manuals used by the Puerto Rico Police warn that it is a potentially lethal weapon.

“Conducting more than three five-second shocks, or more than 15 seconds of exposure against the same person or animal, has a high probability of resulting in a serious health risk or death during an incident,” according to the Puerto Rico Police General Order on the use of the Taser, revised in November 2022.

In the Arecibo Region, officers used more than one electric shock in 14 of the 34 incidents (41%) in which they used a Taser on a person experiencing a mental health crisis, according to CPI’s analysis of the incident reports from 2018 to 2021.

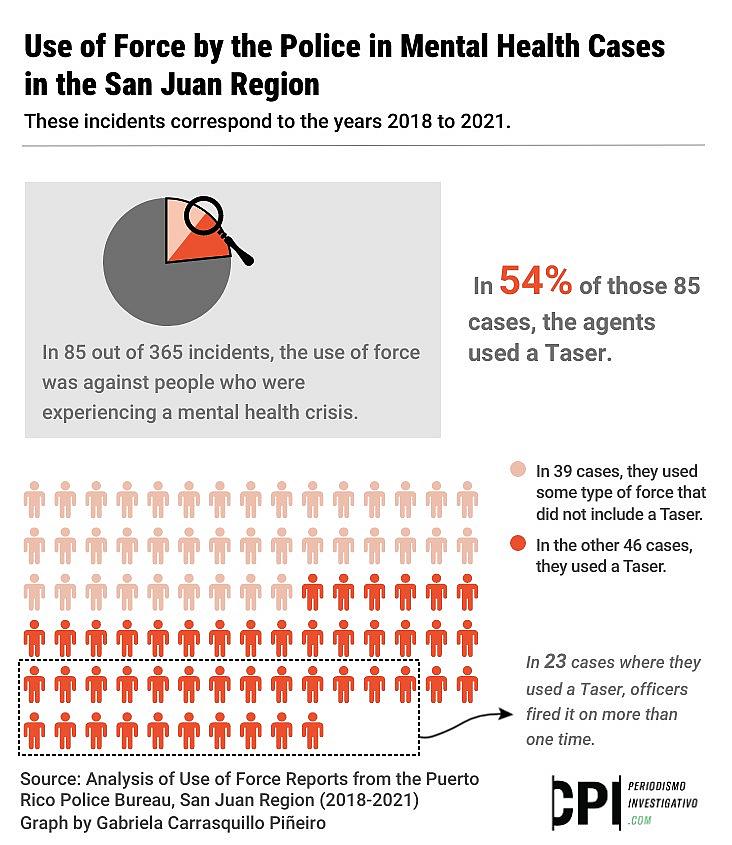

CPI reviewed use-of-force reports in the San Juan Region, where police used Tasers more frequently and did not have a special protocol for addressing mental health calls. The pattern was similar to Arecibo. Among the 365 use-of-force cases reported by police between 2018 and 2021 in the San Juan Region, 85 (23%) occurred against people who were going through an apparent mental health crisis. In 54% of these incidents, the force used was a Taser. In half of the cases in which a Taser was used, officers fired more than once, sometimes discharging a Taser as many as four or five times into the same person.

To identify cases in which force was used against a person experiencing a mental health crisis, CPI reviewed 596 use-of-force incidents described in more that 3,900 pages. All the incidents took place in San Juan and Arecibo between 2018 and 2021. CPI classified the interventions based on the information available in these reports, particularly the accounts of responding officers and their supervisors.

For this reason, it is possible – even likely – that we have omitted some incidents in which force was used against a person experiencing a mental health crisis. In most of these cases, supervisors determined that the use of force was justified.

Greater danger for mental health patients

In 2009, White and his colleague, Justin Ready, published a study of Taser use incidents reported in the U.S. mainland media between 2002 and 2006. Their analysis of 521 articles on different incidents noted that while deaths caused by Tasers are rare events, the risk of death appeared to increase when Tasers were discharged more than once against people experiencing an emotional crisis.

They found that, among news media articles reporting on Taser deployment by police, fatalities were far more commonly reported in cases where a person was experiencing a mental health crisis and had a Taser used against them twice or more.

In an interview with CPI, White explained that Taser discharges cause deep, widespread pain. He knows this from personal experience because during the course of his research, he allowed himself to be shot by a Taser.

“Most times when you think of something that’s painful, it’s very localized. If you cut yourself or if you have a burn, you can have significant pain but basically, it’s just in that one area where you’ve been injured,” White explained. The pain that a Taser provokes is “not localized at all. It’s — basically I felt it in my entire body. I wouldn’t describe it as a superficial pain, it was a deep-in-your-bones kind of pain…It is extraordinarily painful.”

In addition to this immense pain, the Taser essentially paralyzes the person while the electric current is active, White said. Puerto Rico Police officers have used this to control and immobilize those who don’t follow their instructions or resist arrest, CPI’s findings show.

White and Ready also noted in their study that people experiencing a mental health crisis are less likely to comply with police orders, due in part to their state of emotional distress. And this, they suggest, makes it more likely that they will be Tased more than once, increasing their risk of death.

Police tactics for a health problem

In May 2021, Ángel, a 50-year-old mental health patient from the Arecibo Region, was given two electric shocks by police when he resisted being transported to the hospital against his will. It was not the first time that he needed emergency psychiatric help and the responding officers were aware of his history. Nonetheless, when they went to his home to enforce a court order, they decided not to activate the crisis intervention (CIT) group.

“In my presence, Officer [Brenda] Pérez asked [Ángel’s mother] if he was an aggressive person with everyone and she answered that he only got aggressive with her, so Officer Pérez and I chose not to inform the Arecibo area crisis intervention group,” Sergeant Juan D. Ruiz Morales, the shift supervisor on duty, wrote in his use-of-force report.

On a Saturday, police and paramedics arrived at his house to carry out the court order against Ángel, whom CPI is identifying only by his first name to protect his privacy. When they arrived, he was inside the bathroom and said he would come out after taking a shower, according to the use-of-force report filed by police. The officers waited just 15 minutes before one of the paramedics opened the bathroom door, which was unlocked, and told Ángel that he had to go with them.

Ángel initially refused, but after a neighbor intervened, he agreed to leave. A police officer and a paramedic grabbed him by the arms to take him to the ambulance. On the way to the ambulance, Ángel saw his mother and broke free, throwing his fists in the air to prevent them from taking him away, according to Sergeant Ruiz Morales’ report. Ruiz Morales delivered two five-second shocks with the Taser, first on the left side of Ángel’s torso and then on his chest.

After tasing him, the agents threw Ángel on the ground, handcuffed him and took him to the ambulance. The supervisors who issued or signed the reports in the days after the incident — Lieutenant Alexis González Morales, Captain Rafael Asencio Terrón and area commander Israel Rojas Velázquez — determined that the use of force in this intervention “was justified and responsibly done,” that the police officers had followed “the rules and policies” of the bureau, and that the incident did not merit an internal investigation.

Negrón Meléndez, the sergeant in charge of the Arecibo crisis intervention team, said in an interview that one of the most important skills when treating a person going through a mental health crisis is not to rush. “We don’t think about time,” she said. Ángel was not that lucky. Less than an hour passed from the arrival of the police and the use of the Taser, according to the use-of-force report.

Just two months after this incident, in July 2021, police went to the home of Francisco, 46, a resident of the Arecibo Region, because he was threatening suicide. Francisco also had a history of mental health crises, and his sister, who had requested a 408 order for his involuntary hospitalization, had noted that he was being aggressive.

On the way to Francisco’s house, Sergeant Samuel Galloza alerted the crisis intervention team, and CIT-trained Officer Carlos de Jesús went to the house. With Francisco barricaded in his house, the officers decided to force their entry into the residence, and Francisco locked himself in a room, according to the police report. Officer De Jesús remained in communication with him, talking through the closed door for four hours until he convinced him to leave the room to get help.

Although Officer De Jesús’s de-escalation strategy worked, once Francisco left the house, the intervention was again treated as a police matter. Lieutenant Alexis Soberal Serrano ordered his subordinates to arrest Francisco, and the man – who had come out willing to be helped – “tensed up” when they tried to arrest him.

“With my hands, I grab him by the right arm and twist it and take it toward his back,” Soberal Serrano said in his use-of-force report. Although he was not tasered like others in this situation, Francisco – who was going through a mental health crisis – left his house handcuffed, under police custody, and on his way to the police station. From there, paramedics treated him and took him to a hospital in Utuado so he could begin receiving the mental health care he needed.

Mayra Olavarría Cruz, a clinical psychologist and professor at the University of Puerto Rico’s School of Medicine, said police training can be useful so officers learn to deal with the pressures of crisis interventions. But an even better alternative, she said, would be to have officers work alongside mental health professionals on emergency response teams.

“It is not that 100% of the cases will be resolved with that, but [mental health professionals] could de-escalate the situation and could negotiate with the patient,” said Olavarría Cruz, who spent 16 years as an instructor of a crisis prevention program with mental health patients. She added that it would also help if officers who work in these interventions did so without wearing uniform or badges that the patients might associate with violent situations or threats to their safety.

Sergeant Negrón Meléndez, leader of the CIT program in Arecibo, believes that police officers must be trained to handle mental health crisis situations because they will always face them, but that these interventions require a multidisciplinary response.

“Crisis intervention shouldn’t begin with the presence of a police officer. It should be with the presence of a mental health professional,” she said. “Should the service be combined? Of course, we can assist. But, as a police officer, I can say that, from the beginning, mental health must be worked on, not through police intervention, but by a mental health professional.”

This story is published thanks to the support of the USC Center for Health Journalism. It is also part of Fateful Encounters, an ongoing investigative collaboration between MindSite News and the Medill School of Journalism, Media & Integrated Marketing Communications at Northwestern University, exploring police response to mental health crises. The Center for Investigative Journalism in Puerto Rico edited this investigation.