For Sikhs In ICE Detention Centers, Faith Represents Hope

The story was originally published by IndiaCurrents with support from our 2025 California Health Equity Fellowship

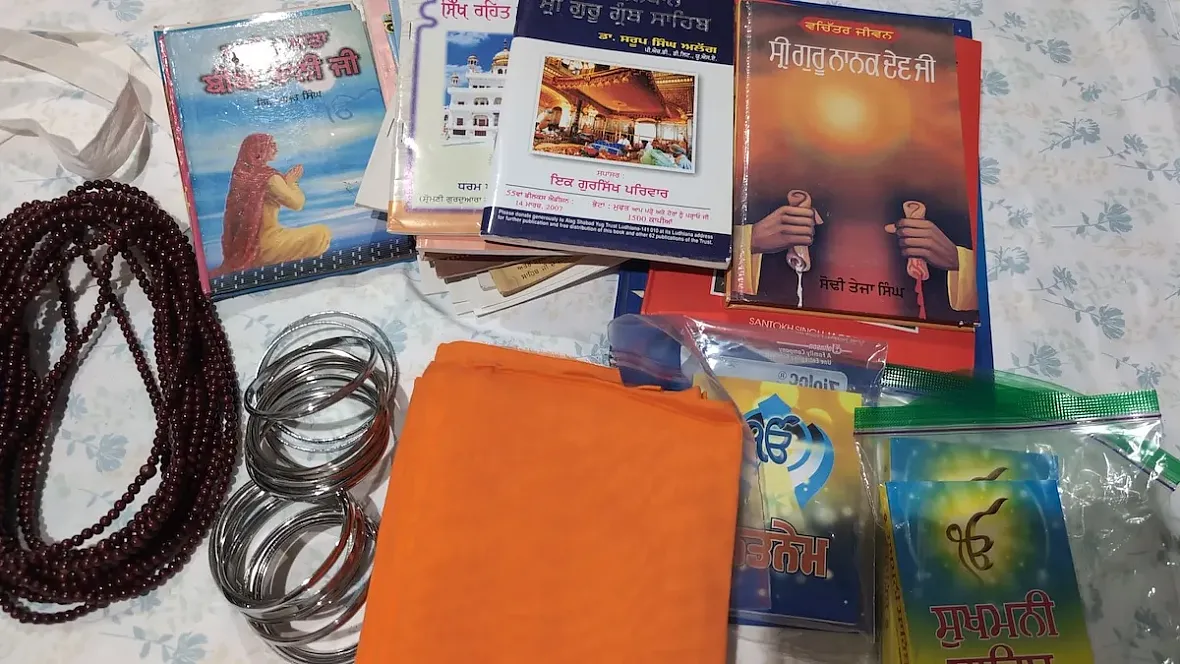

Sikh articles of faith including maalas (prayer beads), karas (metal bracelets), dastaar (turban cloth), and Punjabi books.

Image credit: Simran Singh.

Every Thursday, 33-year-old insurance broker Simran Singh loads up his car with an assortment of items and sets out from his Bakersfield home. On the way, he might make a stop at an Indian grocery store to pick up Punjabi-language newspapers, and then another at the gurdwara to pick up around 50 servings of prashad, a traditional sweet pudding cooked in-house for devotees.

Every Thursday, Simran Singh drives to the Mesa Verde Detention Center in Bakersfield.

Image credit: Simran Singh.

Amid the doom and gloom of Kafkaesque asylum cases, news of bunkmates being transferred, and anxious whispers about impending deportation, the articles of faith that Singh delivers represent a rare glimmer of reassurance inside the four walls of the detention center.

“It is heartwarming to see,” said Singh. “Now they know that there is someone who knows they exist, that they’re not just a number in a facility.”

Indian Immigrants Rising At The Borders

Singh’s initiative began out of curiosity in 2016, when he volunteered with a Sikh community organization to register voters at the gurdwara. Donald Trump was running for his first term as President, and immigration was a hot topic in the news. When he found out that there was a detention center fifteen minutes away from his home, he decided to visit the facility to see if there were any South Asian detainees.

A fifteen-minute drive brings him to the compound of the Mesa Verde ICE Detention Facility, a beige concrete structure surrounded by metal fences topped with barbed wire. After he checks in and picks up a visitor badge, a security guard escorts him from the lobby, past the vending machines, to the cafeteria. Over the next ninety minutes, Singh meets the sixty-odd Sikh detainees held at the detention center. He distributes cloth dastaars that Sikhs use to cover their heads, maalas (prayer beads), karas (metal bracelets), Nitnem Gutke (prayer books), and Punjabi newspapers while chatting with them.

“I didn’t really expect there to be any, and I just thought it’d be an interesting fact-finding journey,” he said. He was surprised to learn that there were, in fact, three Sikh detainees from India at Mesa Verde. At the Program Director’s suggestion, he completed a four-hour volunteer course at the Detention Center, which gave him access to them. The first time he met them, they asked for Punjabi newspapers and Nitnem Gutke or prayer books.

Over the next four years, Singh established a routine of visiting the facility every week, witnessing a steady increase in the number of South Asian detainees, many of whom were Sikhs from India. Between 2016 and 2020, the number rose from three to 40, most of them detained straight after crossing the border. This rise corresponded with an increase in the number of Indians apprehended by the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) at the Southwest and Northern land borders between 2016 and 2019, followed by a sharp drop in 2020 due to COVID-19.

Most of these individuals are from the Indian states of Punjab, Haryana, and Gujarat, fleeing India because of financial insecurity or political persecution, and seeking asylum in the United States. Over months, they journey by air, water, and on foot to reach the U.S. border, only to be detained by Border Patrol or deported to their home country.

For South Asian immigrants, language and cultural barriers create an additional hurdle at the border. Fresno-based immigration attorney Deepak Singh Ahluwalia describes multiple cases of Border Patrol officers reporting inaccurate statements of asylum-seekers because officers cannot understand what the asylum-seekers are saying.

“The language barrier is huge, it’s immense,” he said. “They [Border Patrol] are not equipped with that; I think in 10 years, I’ve met one CBP officer who spoke Punjabi!”

These discrepancies often hurt their asylum cases in the future, said Ahluwalia. Other cultural differences, including attitudes towards mental health and fear of authority, further contribute to the discombobulation that South Asian immigrants face immediately after crossing the border.

“I felt so terrible that I started crying”

For Sikhs, their articles of faith — most notably turbans — have become a contentious issue during border crossings.

Harminder Singh (name changed upon request), a 36-year-old Sikh truck driver who lives in Fresno with his family, fled from his hometown in Punjab with his wife and two children in 2022 because of political persecution. He paid an agent around $180,000 to arrange his family’s travel to the U.S.-Mexico border, a four-month-long journey that took them through the U.K. and Mexico.

Harminder recalls having a headache and feeling queasy when Border Patrol officials detained him and his family at the border crossing at San Luis, Arizona. He asked for medical assistance, but the three officers ignored him, instead directing him to take off his turban. Harminder pleaded with them to keep it on; as a practicing Sikh, he could not take off his turban, an article of faith. He even offered to take it off in private if the officers wanted to inspect him for security reasons, but to no avail.

“My turban is everything for me, I cannot be separated from it,” said Harminder. “To have it taken away from me in front of my kids, it was so terrible that I started crying. My kids also started crying.”

Then, the officers handcuffed him and locked him in a separate room, away from his wife and two children. Inside the room, Harminder vomited twice and called for someone to let him out.

Two hours later, he was released, and his family was transported to a nearby detention facility. Still without a turban, Harminder’s headache grew worse, and he developed symptoms of COVID. “Mucus was flowing out of me like never before,” he recalled. “I asked for a coronavirus test, or at least an antibiotic, but they denied both.”

After two days at the detention center, authorities dropped off Harminder’s family at a church, where their relatives came to pick them up. Social workers at the church gave him a turban and administered a COVID-19 test, which came back positive.

Harminder was one of at least 64 Sikh immigrants whose turbans were “trashed” at the Arizona border around August 2022, according to local media reports. Following advocacy efforts by civil rights groups, the CBP issued new guidance preventing the unnecessary confiscation of Sikh articles of faith. But in February 2025, Indian media reported that Sikh deportees were forced to take off their turbans after they were taken into detention for processing before deportation back to India.

Articles Of Faith Bring Hope, Break Barriers

According to Simran Singh, detainees often do not have access to articles of faith like turbans. Detention Centers might have a budget set aside to source books for the common library, board games, and rudimentary sports equipment for detainees’ recreation. But the budget might not always cover sourcing articles of faith for detainees who follow a variety of religious practices from around the world.

So Singh relied on his own ingenuity and network to source and deliver these items for Sikh detainees.

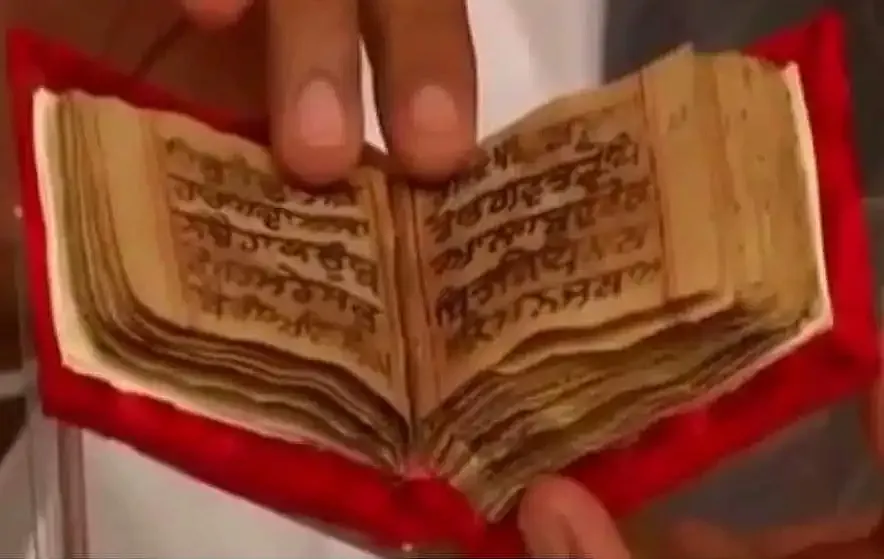

The preserved Nitnem Gutka that belonged to Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth guru of Sikhism.

Image credit: Sajjan Singh on Facebook, accessed via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Punjabi newspapers were easy enough to source from Indian-owned grocery stores, and he had a few Punjabi books at home that he donated to the facility’s library. Nitnem Gutke — hardbound prayer books — presented a problem because the detention center prohibits detainees from keeping hardbound books as personal possessions. And, because they’re holy books, it would be inappropriate to place them in the library among other books, as they might undergo damage. So, Singh reached out to his family members in Los Angeles, who imported soft-bound Nitnem Gutke from India along with other goods for their business. Ziploc bags added a further layer of preservation to the holy books, making them suitable for use by detainees. The same relatives also helped Singh import dastaars or turban-cloths.

He also procured karas (metal bracelets) from stalls set up outside gurdwaras during festivals and ordered a bulk shipment of maalas (prayer beads) online. Maalas, he said, are the most popular because people practicing other faiths like Catholicism, Islam, and Hinduism also use them.

During his meetings with the Sikh detainees, “they would also take back extra maalas to give out to people in their dormitory, to build some kind of relationship,” he said. “If you’re in a dorm with someone from El Salvador or Mexico, they’re primarily speaking Spanish, you’re speaking Punjabi, neither of you is speaking English well, so communication is hard. But now you have something to give to them, and that gesture goes a long way.”

Starting in 2017, he also raised funds and marshaled a group of volunteers to conduct kirtan dewans — Sikh devotional concerts — at California ICE facilities like Bakersfield, Adelanto, and Calexico. At the Calexico dewan, he recalled African detainees coming up to him and asking for the dastaars to use as their traditional headdress.

When Singh started delivering articles of faith to the Mesa Verde Detention Center, he had no idea how much his initiative would grow over the years. But before long, he was hearing from detention centers all over the country; they were seeing a growing number of Sikhs, but had no resources to cater to their religious needs.

Since July 2025, Singh has supplied thousands of dastaar, maalas, karas, and Nitnem Gutke to 18 detention centers, ICE processing centers, and correctional facilities across Arizona, California, Colorado, Indiana, Pennsylvania, Texas, Louisiana, and Virginia. As the Trump administration ramps up its crackdown on undocumented immigrants, the need for services like his is likely to increase.

“ICE picking the lowest hanging fruit”

In early 2020, the pandemic put a pause on Singh’s visits as the facility rolled back its volunteer visitation program. That same year, detainees filed a class action lawsuit against ICE and the GEO Group, the private company that ICE contracts with to manage the Mesa Verde Detention Center and several others across the country.

The plaintiffs alleged that the Mesa Verde Detention Center was overcrowded and, as a result, there was a failure to follow social distancing norms and other COVID-related precautions. In response to the lawsuit, a 2022 settlement stipulated population limits, reducing the number of detainees housed in the Mesa Verde Detention Center from its capacity of 400 to less than 75, according to an ACLU source reported by the local media. During this period, Singh did not visit the detention center since it did not house a lot of South Asian detainees.

In June 2025, the population limits expired, and Singh resumed his weekly visits to the Mesa Verde Detention Center. He reports a rising number of detainees now that the population limits are not applicable; on a recent visit, he met with 65 South Asian detainees, the most ever. Singh estimates that more than half of them were Sikhs.

Immigrants are being detained from their regular immigration check-ins as part of the government’s ongoing crackdown on immigrants.

Image credit: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

He noted that between 2016 and 2020, most of the detainees were recent immigrants who were transferred to the center directly from the border, or a few months after crossing over the border. Now, in 2025, he sees a trend emerging among the new arrivals: most of them are being detained at their immigration case hearings and during routine check-ins with ICE officers.

“They [Immigrants] don’t want to miss these visits, so they [ICE] are having these immigrants walk into what ends up being a trap,” said Singh. “It’s ICE picking the lowest hanging fruit to meet their numbers.”

On his latest visit, when interacting with the detainees from the women’s dormitory, he met with a forty-something-year-old Sikh woman from Fresno, who told him that she and her son were both detained from their ICE check-in. She said that her son was also detained at the same facility, but the two had not spoken a word to each other since their detention because male and female detainees are not allowed to interact at all. A few minutes later, when Singh met with the male detainees, he identified the woman’s son and conveyed his mother’s message to the young man in his twenties. The message was that she was alright and that he should not worry about her.

“Like putting a bandage”

For many detainees, Singh is their only point of contact with the outside world. Telephone calls to family back home in India are available, but at an exorbitant rate of $0.85/minute, which is not commensurate with the $1/day wage that they can earn through cleaning jobs within the facility. Even for those with family in the United States, planning visits can be an expensive proposition, especially for detainees from blue-collar backgrounds whose families live in another state.

Simran Singh (middle) during a group tour of the Bakersfield Detention Center that he organized to raise awareness about Sikh detainees among the Sikh diaspora.

Image credit: Simran Singh.

During Singh’s visits, over portions of prashad, detainees reveal to him the nerve-wracking details of their stories, unloading some of their physical, mental, and emotional turmoil onto him. He reckons they’d open up even further if he saw them for a sustained period of time, but the turnover is such that most detainees are in the detention center for 6-8 weeks before being released, transferred to another facility, or worse, deported. Every Thursday, Singh finds that some of the familiar faces from previous visits have been replaced by new arrivals.

“I don’t know how it ends, right?” he said, “I just show up and either they’re going to be there or they’re not going to be there. I don’t get that closure or find out what happens once they’re gone.”

More detainees are expected to arrive at the Mesa Verde Detention Center in the weeks to come. Simran Singh continues to liaise with the facility’s staff to gauge how many might be Sikh, so that he can make arrangements to deliver enough articles of faith.

“It’s a big morale booster. They have a way to keep their identity in a place where everyone’s wearing the same clothes, waking up at the same time, following the same schedule, day in, day out for months and years at a time,” said Singh. “It’s like putting a bandage on something that requires a major operation.”