Southern California emergency room use has actually risen after the passage of Obamacare

This story was reported in partnership with the California Data Fellowship, a program of USC’s Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Southern California ERs look for answers to the crush of newly insured patients at their doors

Emergency Services at the Antelope Valley Hospital. (Photo by David Crane, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

First in a four-part series that examines emergency room use in Southern California.

Homeless people and a growing number of newly insured young adults are flooding Southern California’s emergency departments for non-life threatening illnesses, years after proponents of the Affordable Care Act promised that better health coverage would divert people away from ERs, according state data and public health experts.

State data show the opposite has happened: Emergency department visits, including those that resulted in hospital admissions, grew an average 4 percent every year from 2010 to 2016.

The rise in emergency department use persists more than three years after the main provision of the Affordable Care Act kicked in, at a pace more than five times the average year-to-year population gains of Greater Los Angeles.

California emergency rooms this decade saw a sustained growth in visitors pre- and post-Affordable Care Act. Visits from 1997 to 2006 hovered around 9 and 10 million. By 2010, there were 11.6 million, and by 2016 there were 14.6 million

A growth in homelessness, a newfound comfort among the previously uninsured and a widespread lack of access to ER alternatives such as primary care physicians are among the reasons why.

Hospitals from the northernmost edges of Los Angeles County down to the San Diego County line have seen massive shifts as more prospective patients gained medical insurance: Private or member-only hospitals such as Kaiser began to see more patients with Medi-Cal, while public hospitals such San Bernardino County’s Arrowhead Regional Medical Center lost patients and have reported fewer people in their emergency departments.

A Southern California News Group analysis of data from the state’s Office of Statewide Planning and Development found, from 2010 to 2016:

- Visits to the Southern California’s emergency departments swelled 27 percent, reaching 6.5 million in 2016. It’s as if 1 of every 3 people in the region visited an emergency room that year. Southern California’s population grew just 5 percent in that time, so more people only accounts for part of the trend.

- Medi-Cal recipients grew from one-quarter to nearly half of emergency room users in Southern California, including Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

- As the share of patients with Medi-Cal rose, uninsured ER visitors fell from 18 to 8 percent; visitors with private coverage slipped from 32 to 26 percent.

- Despite the jump in visits and admissions, Southern California’s ER average wait times — minutes people spend in an emergency department before they’re seen by a health care professional — appeared to improve slightly in 2016 since 2013, just before the ACA went into full effect.

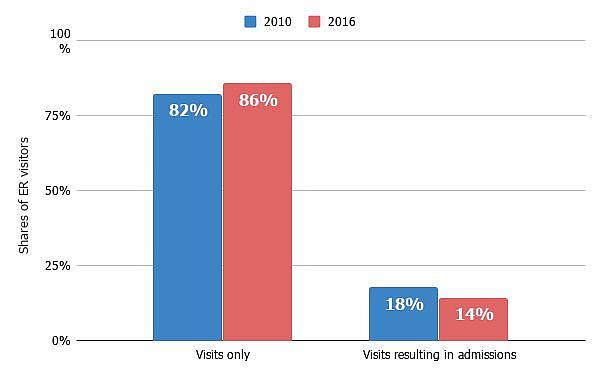

- Raw counts of both ER visits and admissions rose, but the portion of visitors who ended up staying in a hospital bed dipped from 18 to 14 percent, indicating more patients who were simply treated and released.

- The high number of homeless people with mental health needs who also were enrolled into Medi-Cal has risen sharply, and is most noticeable in California. At the same time, a shortage of psychiatric beds, and mental and behavioral health specialists in California has contributed to the rush to the ERs. The Golden State shows the lowest ratios of specialists, especially in the Inland Empire and San Joaquin Valley, according to California’s Current and Future Behavioral Health Workforce, a report from the University of California, San Francisco.

Those who have been opposed to the Affordable Care Act may say the data prove the system is failing, that these trends hurt patients, cost taxpayers too much and place even more stress on emergency departments and physicians.

But health policy experts and various organizations say that the system, given time, will even out — unless the Trump Administration’s threats to fully dismantle the ACA come to fruition.

Others say the high number of visits should have been anticipated as emergency room use by those who were once uninsured.

“We see the increase in ED use by Medi-Cal enrollees as a function of people becoming eligible for Medi-Cal and, at least initially, not having an established usual source of care,” said Catherine Teare, associate director of high-value care at the California Health Care Foundation. “The ED utilization rate among Medi-Cal enrollees has not changed much — meaning that the use of EDs among these new enrollees was not much different from the use of other enrollees.

“We would expect to see number and rate decline over time, and some plans are already reporting that to be true.”

Still, the number of visits to emergency departments is worth the scrutiny and will show if the Affordable Care Act promises to deliver.

Health coverage is one thing, health policy experts say, but access to care good care is another.

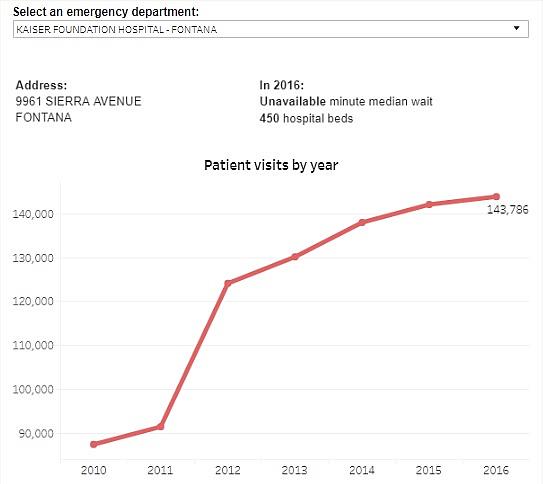

More than three-quarters of Southern California emergency rooms recorded increased patient numbers in 2016 compared to 2010

Sources: Office of Statewide Planning and Development, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (Ian Wheeler / SCNG)

A snake swallowing an elephant

Think of California’s health care landscape as a snake swallowing an elephant, said Anthony Wright, executive director for Health Access, a California-based consumer advocacy group.

The elephant is the large swath of Californians who went from being uninsured to gaining health coverage in just a few years. The share of uninsured Californians fell from 17 percent in 2013 to about 7 percent in 2015.

More than 1-in-3 Californians now carry Medi-Cal, the state’s version of Medicaid, including many homeless people who had no insurance before.

Like the snake, a network of care unprepared for the influx is trying to digest the newly insured who now have some form of coverage, Wright said.

Suddenly, people who withheld using the emergency room for fear of high bills were showing up at the doors, Wright added.

“For many people, the emergency room bill is the biggest bill in their lifetime. If you don’t have coverage, it’s a very scary prospect,” Wright said. “You have to be in a world of hurt to risk that. But if you are covered, then you have the ability to get the care you need.

“It may be that the emergency department is the one place that you go to that you know you can get the care you need. If you do have great utilization as a result, we think that’s a good thing.”

Millennials made up their fair share of ER appearances — those ages 20-29 were the most common visitors in 2016, making up 16 percent of patients in the region’s emergency departments.

Baby boomers, too, have boosted their ER presence with a 53 percent increase in visits and admissions so far this decade. In 2016, area emergency rooms recorded 216,725 encounters with patients in their 60s, data analyzed by the Southern California News Group show.

Wright said California began Medi-Cal enrollment early. An experiment involving 500,000 new enrollees before the ACA offered a glimpse of whether or not the health care system in California was prepared. Wright said the snake eating the elephant effect was present then too, but over time, the learning curve became easier for the newly insured.

“It was about two years for the system to absorb the pent up demands of the needs the patients had,” Wright added.

He said it may take a little longer after the mass expansion brought on by the ACA.

“This was such an important and big expansion that we’re still sorting things out both in terms of getting the data and figuring out what it means,” Wright said.

While still rising, the average growth rate of Emergency Department visits has slowed in recent years. In 2017, treat-and-release visits to California’s ERs only grew by 1.8 percent, according to preliminary data from OSHPD. That’s down from 2016, when visits grew by 2.3 percent, and from 2015 and 2014, when visits grew by 7 percent and 6 percent respectively.

Southern Californians such as Jennifer Glasier, of Tustin, say they feel the current system can be uneven and unfair — that too many people people will remain at-risk unless a quicker solution is found.

Despite the Affordable Care Act’s provision that insurers can’t deny coverage of people with pre-existing conditions, Glasier said her husband has been cast aside. He had kidney cancer and since 2015, she has paid high premiums to keep him covered on private insurance. They live in a motel, a result of losing their condo in Irvine because of of high medical bills. Both work, but neither qualify for Medi-Cal.

“I keep fighting with people,” Glasier, 42, said. “I pay every month for health insurance, but we’re denied basic care.”

So she takes her husband to the emergency room at Saddleback Medical Center. She’s been there eight times.

“We don’t have the money to fight (the system),” she said.

An exact figure on how many people who stated they were homeless while being enrolled into Medi-Cal is unavailable, but estimates based on a statewide pilot program called Whole Person Care show a glimpse. In 2016, Orange County estimated on its funding application there were about 11,500 homeless Medi-Cal beneficiaries, Teare said.

In Los Angeles County, about a third of about 58,000 people deemed homeless last year reported being diagnosed with a mental illness.

“Mental health patients are being taken to the ERs because the mental health system is in crisis,” said Jan Emerson-Shea, spokeswoman for the California Hospital Association. “There’s no other place in many communities.”

In time, the health system of care among emergency departments, urgent cares and community clinics will digest the mass influx of Medi-Cal patients, but several pieces still need improvement, added Emerson-Shea.

“It is clear, we’ve got a systemic issue across the state that looks like ERs are the only part of the health care system open 24/7 and are required to take everyone at the door,” Emerson-Shea said. “That’s a good thing, but also we’ve become a backstop for every social issue. The ER is often the place to go.

“That’s not what the ER is for.”

ER visits and the ACA

And that’s where the ACA has come up short, Emerson-Shea and others said. During a 2009 town hall meeting to promote health care reform and the eventual signing of the ACA in 2010, former President Barack Obama said signing people up in insurance would eventually drive down costs and visits to emergency departments.

“One of the areas where we can potentially see some saving is a lot of those patients are being seen in the emergency room anyway, and if we are increasing prevention, if we are increasing wellness programs, we’re reducing the amount of emergency room care, then that frees up doctors and resources to provide the kind of primary care that will keep people healthier, but also allow them to see more patients and hopefully give more time to patients, as well,” Obama said.

“This is where ACA hasn’t lived up to promise,” Emerson-Shea added. “Unfortunately, one of the goals of the ACA was to get them out of the ER, and get them to doctors and prevention programs. That’s been one of the disappointing aspects of the ACA.”

Although Obama and his supporters spoke often of long wait times in the emergency departments, and how ERs would no longer be the place for primary care, a knot of issues persisted and produced the glut of visitors in the waiting rooms and along the hallways of hospitals.

Baby boomers: Known as the “gray wave,” about 4 million Californians will be 65 and older by 2030 and their age-related health needs will rise, according to a report by the Public Policy Institute of California. A 2016 report from OSHPD showed falls among seniors that resulted in emergency room visits rose 38 percent since 2010.

Lack of primary care physicians: A report by the University of California, San Francisco found that many California regions, including Los Angeles County and the Inland Empire, fall below the desired benchmark of 60 primary care physicians per 100,000 people.

Low Medicaid reimbursement rates: California’s primary care physicians receive 70 cents to the dollar from the government, the second lowest in the nation, behind Rhode Island, according to data compiled by Kaiser Health Foundation.

While the ACA has made strides in health care coverage, all those issues expose how there is still more to do in terms of making sure that people have access, Emerson-Shea said. “ER numbers are (high) because of a lack of additional doctors, willing to see Medi-Cal patients.”

The lack of primary care physicians also has caused a domino effect hitting patients such as Loreal Ybarra, 62, a resident of Orange.

Ybarra said she’s had private insurance before but illness led her to leave her job; now she’s on Medi-Cal.

Over the past few years, Ybarra said she’s used nearby St. Joseph Hospital’s emergency department about five times. CalOptima, Orange County’s health organization that administers her Medi-Cal, sent her to a clinic, where an overwhelmed primary physician spent only 10 minutes with her, she said.

Because of the brisk care, Ybarra instead relies on St. Joseph’s ER to treat her heart problems, visual impairment and other issues, competing for care with others whom she says simply come in with colds.

“The care is not the same,” Ybarra said of the changes after the Affordable Care Act. “The doctors (in emergency departments) don’t act like doctors anymore. They act like this is an assembly line. They say they are so overwhelmed with patients and they’re not taking the time.

“Everybody is passing the buck to someone else.”

She said she has waited up to six hours in the waiting room.

Less time in the waiting room

While long waiting room stories are common, minutes spent waiting to be seen at many emergency departments in Southern California appeared to improve, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which surveys patients to report how long the average ER visitor waits to be seen. Data were not available for about a quarter of the region’s hospitals.

The Southern California News Group compared median waits in 2016 to a benchmark: median waits over four years, 2013 to 2016.

The biggest improvements in 2016 were seen in Los Angeles and Orange counties, where ERs collectively knocked five minutes off the four-year median, to 25 minutes.

Anaheim Global Medical Center, a 189-bed hospital about a mile south of downtown Anaheim, slashed its median emergency room wait in 2016 to 13 minutes from 43 minutes since 2013, despite seeing a growing number of patients every year.

ER visitors surveyed at 199-bed PIH Hospital in Downey waited 39 minutes in 2016, nearly an hour less than the facility’s median over the four-year period.

Results at inland ERs were mixed: Riverside County’s median ticked up three minutes to 33 minutes; San Bernardino County’s was unchanged at 32 minutes.

At 51-bed Palo Verde Hospital in Blythe, the only emergency room around for miles, median waits from 2013 to 2015 were around 10 minutes. In 2016, they spiked to more than an hour and a half; the facility saw 9,877 patients that year, around its normal burden.

[This story was originally published by the Los Angeles Daily News.]